Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Einsatzgrϋppen

Einsatz Group A Einsatz Group B Einsatz Group C Einsatz Group D Babi Yar Articles Einsatz Leaders Einsatzgruppen Operational Situational Reports [ OSR's #8 - #195 ]

| |||||||||||||

Einsatzgruppen A

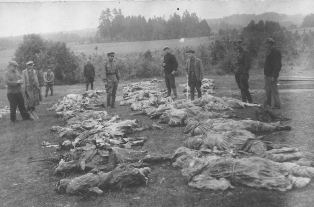

Mass Murder in Lithuania

In Kovno 1,500 Jews were killed on the night of 25 June and 2,300 on the 26 June 1941.

Dr Franz Walter Stahlecker the head of Einsatzgruppen A in the Baltic States was particularly pleased with the understanding attitude adopted by the Wehrmacht, but this was only half the story.

An orderly occupation is not promoted by allowing 3,800 people to be killed in the streets of a city normally as stodgy as Stockholm. Field – Marshall von Leeb, commanding Army Group North, ordered von Kuchler of the 18th Army to stop such incidents recurring. Stahlecker had now to take responsibility for the killings himself.

We hear no more of the Lithuanian journalist Klimatis, whose four political groups so distinguished themselves on 25 and 26 June, but Stahlecker picked 300 of these citizens to serve in his Einsatzgruppe.

Henceforward the Lithuanians were to do the work for which they could be trusted, under a different authority, and seven months later Stahlecker was able to write that eight Lithuanians served in his commandos to one German.

By the summer of 1942, whole regiments of Lithuanian police had been sent to Poland, White Russia and Latvia to guard the camps and ghettos to man the extermination camps, and to cut down cringing old people and children in the streets during the “actions.”

A few days after the massacre in Kovno, Stahlecker summoned a council of the Jewish community and declaring that the Germans “had no reason to intervene in their differences with the Lithuanians,” recommended to them the virtues of moving into a ghetto – for which Stahlecker found the Viriampole district particularly suitable, since only one bridge across the Memel connected it with the town.

But there were too many Jews to be fitted into Vriiampole, even if flight and deportation had reduced their numbers to 24,000. On 11 July therefore Stahlecker ordered a “cleansing action.” All Jews not wanted by a labour office were to be committed to prison and executed daily in batches of fifty to hundred.

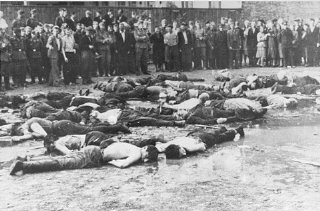

The first executions at the Vilna killing site at Ponary took place on the 8 July 1941 one hundred Jews at a time were brought from the city to Ponary, to a waiting zone.

Here in what had been a popular holiday resort for Vilna Jewry, they were ordered to undress and to hand over whatever money or valuables they had with them. They were then marched naked, in single file, in groups of ten or twenty at a time, holding hands to the edge of the pits dug by the Soviet Army to store fuel.

They were then shot down by rifle fire, after they had fallen into the pit, no attempt was made to see if they were all dead. If anyone moved another shot was fired. The bodies were then covered from above, with a thin layer of sand and the next group of naked prisoners led from the waiting area to the edge of the pit. From where they had waited, the people had heard the sound of rifle fire but had seen nothing.

German soldiers described massacres in July 1941.

A driver’s statement:

I cannot whether we arrived in Ponary on 5 or 10 July 1941. While we were repairing our vehicles – I can no longer tell whether it was on the first or second day of our stay there – I suddenly saw a column of about four hundred men walking along the road into the pine wood.

They were coming from the direction of Vilna. The column which consisted exclusively of men aged between twenty-five and sixty, were led into the wood by a guard of Lithuanian civilians.

The Lithuanians were armed with carbines, the people were fully dressed and carried only the barest essentials on them. As I remember, the guards wore armbands, the colour of which I can no longer recall.

I do remember that Hamann and, I think Hechinger went off after the column. About an hour later Hamann returned to our quarters. He was pale and told me in an agitated manner what he had witnessed in the wood.

His actual words were, “You know the Jews you saw marching past before? Not one of them is still alive.” I said that this couldn’t be the case, whereupon he explained to me that all the men had been shot. Any of them that weren’t dead after the shooting had been given the coup de grace.

The very next day – I think it was around lunchtime – once again I saw a group of four hundred Jews coming from the direction of Vilna going into the same wood. These too were accompanied by armed civilians. The delinquents were very quiet. I saw no women or children in either of the two groups.

Together with some of my colleagues from my motorised column I followed this second group. As I recall the NCO’s Riedl, Dietrich, Schroff, Hamann, Locher, Ammann, Greule and possibly some others whom I can no longer remember came with us.

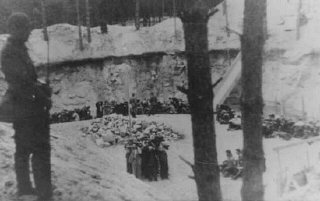

After we had followed the group for about eight hundred to a thousand metres we came upon two fairly large sandpits. The path we had taken ran between them both. The pits were not joined but were separated by the path and a strip of land.

We overtook the column just before we reached the pits and then stopped close to the entry to one of them – the one on the right. I myself stood about six to eight meters from the entry.

To the left and right of the entry stood an armed civilian – the people were led into the gravel pit in small groups to the right by the guards. Running around the edge of the pit there was a circular ditch which the Jews had to climb down into.

This ditch was about 1.5 metres deep and about the same again in width. Since the ground was pure sand the ditch was braced with planks. As the Jews were being led in groups into the pit an elderly man stopped in front of the entrance for a moment and said in good German, “What do you want from me? I am only a poor composer.”

The two civilians standing at the entrance started pummelling him with blows so that he literally flew into the pit. After a short time the Jews had all been herded into the circular trench.

My mates and I had moved up close to the entry to the pit from where we could see clearly that the people in the ditch were being beaten with clubs by the guards, who were standing at the side of the trench.

After this, ten men were slowly led out of the ditch – these men had already bared their upper torsos and covered their heads with their clothes. I would also like to add that on the way to the execution area the delinquents had to walk one behind the other and hold on to the upper body of the man in front.

After a group had lined up at the execution area, the next group was led across. The firing squad, which was made up of ten men, positioned itself at the side of the path, about six to eight metres in front of the group.

After this, as far as I recall, the group was shot by the firing squad after the order was given. The shots were fired simultaneously so that the men fell into the pit behind them at the same time.

The 400 Jews were shot in exactly the same way over a period of about an hour. The shooting happened very quickly. If any of the men in the pit were still moving a few more single shots were fired on them. The pit into which the men fell had a diameter of about fifteen to twenty metres and was I think five to six metres deep.

From our vantage point we could see into the pit and was therefore able to confirm that the 400 Jews who had been shot the previous day were also in there. They were covered with a thin sprinkling of sand. Right on top, on, this layer of sand, there was a further three men and a woman who had been shot on the morning of the day, in question. Parts of their bodies protruded out of the sand.

After about one hundred Jews had been shot, other Jews had to sprinkle sand over their bodies. After the entire group had been executed the firing squad put their rifles to one side. This gave me the opportunity to talk to one of them. I asked him whether he could really do such a thing like that, and pointed out the Jews had done nothing to him. To this he answered, “Yes – after what we have gone through under the domination of Russian Jewish Commissars, after the Russians invaded Lithuania, we no longer find it difficult.”

During the course of our conversation he told me that he had been suspected of spying by the Russians. He had been arrested and had been thrown in and out of various GPU prisons, although he was in no way guilty.

He told me had only been a lorry-driver and had never harmed a soul. One of the methods they used to make him confess was to tear out his fingernails. He told me that each of the guards present had had to endure the most extreme suffering. He went on to tell me that a Jewish Commissar had broken into a flat, tied up a man and raped his wife before the man’s very eyes. Afterwards the Commissar had literally butchered the wife to death, cut out her heart, fried it in a pan and had then proceeded to eat it.

I was also told by comrades that in Vilna a German soldier had been shot dead from a church tower. For this another 300-400 Jews were executed in the same quarry. In this connection, I would also like to say that the very next day once again about the same number of Jews were led along the road into the wood.

Apart from that one day I did not go to the execution area again. I can only say that the mass shootings in Ponary were quite horrific. At the time I said: “May God grant us victory because if they get their revenge, we’re in for a hard time.”

Co – driver’s statement

As already mentioned, we arrived in Ponary one afternoon in the first week of July 1941. The next day we heard rifle and machine gun fire coming from the woods to the south of Ponary. Since we were behind the front we wanted to get to the bottom of the matter. I can no longer remember now exactly whether it was during the morning or in the early afternoon that we went off to find out where the shooting was coming from.

Anyway, I set off with Greule, Hoding, Wahl and Schroff, who were all members of my unit, in the direction of the woods where the shooting was coming from. When we arrived at the spot, we saw people, who we subsequently learned from the leader of the squad were Lithuanians, in the act of carrying out mass shooting of Jews. On the path which ran between the two pits there was a light-machine – gun, pointing to the left, being used by the Lithuanians.

In front of the machine-gun, standing by the edge of the pit, were ten delinquents, who were shot with the machine-gun straight into the pit. I actually looked into the pit and saw that the bottom was already covered with bodies.

In the ditch that had been excavated on the other side of this execution area were the Jews who had not yet been shot. They were all men of different ages. I saw that they had to take off their shoes and shirts and throw them on to the side of the trench.

The Lithuanians standing above were rummaging through these things. I also noticed that at one spot in front of the ditch there was a big mountain of shoes and clothes. While the Jews in the trench were getting undressed the Lithuanians beat them with heavy truncheons and rifle-butts.

They were then led out of the trench ten at a time to stand in front of the machine-gun. The leader of the Lithuanians spoke good German and we went up to him and asked what was going on, saying that this was a downright disgrace. He explained to us that he had once been a teacher at a German school in Konigsberg.

For this the “Bolsheviks” had torn out his fingernails. Moreover, some of the members of the immediate family – parents, brothers and sisters – of this young Lithuanian who was doing the shooting had been captured at the station by the Bolsheviks before the arrival of the German troops and were to have been transported to Siberia.

The transport did not take place because of the arrival of the German soldiers. As a result all the people who were locked up in the wagons starved to death. Why they were now shooting these Jews, if indeed this Lithuanian’s story corresponded with the truth, which I found highly improbable, and whether these particular Jews were the ones who had been involved in that action, he did not tell us.

On one of the last days – it was the third or fourth day of our stay in Ponary, I can no longer remember exactly now – I went to the execution site once again. If I recall correctly, no more shooting could be heard that day and I wanted to look at the place again. I do not remember who went with me.

When I reached the execution area there was a man in a grey uniform standing on the path between the two pits who had been gesturing at us to keep away from a long way off. We kept going, however, and when we got close to him I said there was no need to make a fuss, as we had already seen everything.

As we approached I saw that he was wearing a dark coloured band on his left forearm with the letters “SD” embroidered on it. I now saw that slightly to one side there was a coach with two horses, a landau. On the box of the coach stood a second SD man whom I did not look at more closely. In the coach sat two very well- dressed elderly Jews.

I had the impression that these were high-class or important people. I inferred this because they looked very well groomed and intelligent and “ordinary” Jews would certainly not have been transported in a coach.

The two Jews had to climb out and I saw that they were both shaking dreadfully. They apparently knew what was in store for them. The SS man who had initially gestured to us to keep away was carrying a sub-machine gun, he made the two Jews go and stand at the edge of a pit and shot both of them in the back of the head, so that they fell in.

I can still remember that one of them was carrying a towel and a soap box which afterwards also lay in the trench. I would also like to say that we all said to one another what on earth would happen if we lost the war and had to pay for all of this.

At Ponary, outside Vilna, the shootings had continued without respite. A Polish journalist, W. Sakowicz, who lived at Ponary, and who was himself killed during the last days of German rule in Vilna, noted in his diary:

27 July 1941 Sunday

Shooting is carried on nearly everyday. Will it go on for ever? The executioners began selling the clothes of the killed. Other garments are crammed into sacks in a barn at the highway and taken to town.

People say that about five thousand persons have been killed in the course of this month. It is quite possible, for about two hundred to three hundred people are being driven up here nearly every day. And nobody ever returns.

30 July 1941 Friday

About one hundred and fifty persons shot. Most of them were elderly people. The executioners complained of being very tired of their “work”, of having aching shoulders from shooting. That is the reason for not finishing the wounded off, so that they are buried half alive.

2 August 1941 Monday

Shooting of big batches has started once again. Today about four thousand people were driven up, shot by eighty executioners, all drunk. The fence was guarded by a hundred soldiers and policemen.

This time terrible tortures before shooting. Nobody buried the murdered. The people were driven straight into the pit, the corpses were trampled upon. Many a wounded writhed with pain. Nobody finished them off.

On 31 August 1941 in Vilna, before the ghetto had been established there, a young Jew, Abba Kovner, went to the Jewish Council building to try and find out about the whereabouts of some of his friends who had been taken away in the raids and abductions of the previous weeks.

“I still thought that part of these people, or most of them, would return,” he later recalled. Early that afternoon, the predominantly Jewish section of Vilna was surrounded by an Einsatzkommando unit, together with several hundred armed Lithuanians.

It was announced that any Jew who left his home would be killed, and that a search was in progress for those guilty of ambushing a German patrol. “The streets were surrounded,” Abba Kovner recalled, “but again a few hours went by, and nothing happened.”

“Then, when the sun set, “the action” began, Kovner recounted:

“People were taken out of their flats, some carrying a few of their possessions, out of all the courtyards, out of all their flats they were driven out with cruel beatings.

I don’t know whether out of wisdom or instinct or momentary weakness I found myself in a stairway, in a dark recess there and I stood there. Out of a small window I saw what was happening in that narrow street.

Until one o’clock, past midnight, this operation was still in progress. During those hours, at midnight I saw from the other courtyard on the other side of the street, it was 39 Ostrashun Street, a woman was dragged by the hair by two soldiers, a woman who was holding something in her arms.

One of them directed a beam of light into her face, the other one dragged her by her hair and threw her out on the pavement. Then the infant fell out of her arms. One of the two, the one with the flashlight, I believe took the infant, raised him into the air, grabbed him by the leg.

The woman crawled on the earth, took hold of his boot and pleaded for mercy. But the soldier took the boy and hit him with his head against the wall, once, twice, smashed him against the wall.

That night, 2,019 Jewish women, 864 men and 817 children were taken from Vilna in trucks to the pits at Ponary and murdered. Their fate was unknown to those who remained behind.”

Among those taken to Ponary on the night of 31 August 1941 were many Jews who were being held in prison, after having been arrested in the previous weeks, among them Dr Jacob Wigodsky and the young Jewish historian Pinkus Kohn. The fate of those taken to Ponary was still unknown.

But on 3 September 1941 a Jewish woman arrived in the city, bandaged, barefoot, and with dishevelled hair. Her name was Sonia. In the street she spoke to a Jewish doctor, Meir Mark Dvorjetsky – she had come she said from Ponary. No, it was not a labour camp, and then she told the doctor her story:

“She and her two children had been among the Jews seized, imprisoned and then taken out of the city on 31 August – how they were brought to Ponary, how Jews were trying to reckon with their own consciences, how they were trying to confess their sins before death, how she had heard shots and saw blood and fell.”

As the doctor later recalled:

She was among the corpses up to sunset and then she heard the wild shoutings of those who carried out the murder. She somehow or other managed to get out of the heaps of corpses, she got to the barbed wire entanglements – she managed to cross them and she found a common Polish peasant woman who bandaged her wounds, gave her flowers and said, “Run away from here, but carry flowers as if you were a common peasant, so that they shouldn’t recognise that you are a Jewess.”

And then she came to me. She un-wrapped the bandage and I saw the wound. I saw the hole from the bullet and in the hole there were ants creeping. Dvorjetsky hurried to a gathering of Vilna Jews to tell them the story. “This is not a labour camp where you’re going to be sent to, he said. “This is something else.”

But they could not believe him – “You are the one who is a panic monger,” they replied. “Instead of encouraging us, instead of consoling us, you are telling us cock-and-bull stories about extermination. How is it possible that the Jews will be simply taken and shot.”

Despite the establishment on 6 September 1941 of two ghettos, the “large” and “small” , the killers returned , taking to Ponary a further 3,434 Jews on 12 September and 1,267 five days later.

The Nazis chose the Day of Atonement for yet another raid and execution at Ponary, the men were shot first, then women. Even those who had not been killed outright, could not survive the whole day in the pit, lying there wounded as more and more bodies fell on top of them. Only towards evening, when the last of the women were being shot, did a few of those who were only wounded have some small chance of remaining alive until it was dark, and then of creeping away unseen – naked, bleeding, crushed, but alive.

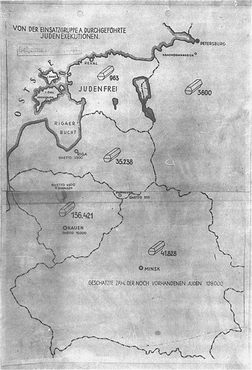

From the end of June 1941 to the end of December, at least forty-eight thousand were murdered at Ponary. After the killings of 3 September, six are known to have crawled out of the pit alive, and survived. All of them were women. One of the survivors of the October killings, Sara Menkes, returned to Vilna, where she told Abba Kovner the story of a former pupil of his, Serna Morgenstern.

At the edge of the pit, Sara Menkes recalled:

“They were lined up, they were told to undress, they undressed and stood only in their undergarments and there was this line of the Einsatzgruppen men – and an Officer came out, he looked at the row of women and he looked at this Serna Morgenstern.

She had wonderful eyes, a tall girl, long braided hair – he looked at her searchingly for a long time and then he smiled and said, “Take a step forward.” She was dazed as all of them were.

No one wept anymore, no one asked for anything – they must have been paralysed and she was so paralysed she did not step forward and he repeated the order and asked, “Hey don’t you want to live? You are so beautiful. I tell you to take one step forward.”

So she took that step forward and he told her, “What a pity to bury such beauty under the earth. Go, but don’t look backward. There is the street. You know that boulevard, you just follow that.” She hesitated for a moment and then she started marching, and the rest, Sara Menkes told me, “We looked at her with our eyes – I don’t know whether it was only terror or jealousy, envy too, as she walked slowly step by step and then the Officer whipped out his revolver and shot her in the back.”

During the above mentioned killings on 24 October 1941 the Germans seized four thousand Jews who did not have work –passes and took them to Ponary. In vain the recently appointed head of the Jewish Council Jacob Genns, appealed to the Germans for additional passes.

Thousands of Jews hid in cellars, or in attics, but groups of Lithuanians went from house to house in search of them, often returning several times to the same house. In many of these cellars Jews resisted the Lithuanian “hunters” and refused to leave. They were shot dead on the spot.

In two days, more than 3,700 Jews were taken to Ponary and murdered or killed in the cellars – of those killed, according to the precise German statistics, 885 were children. Heniek Grabowski was sent by the Jews of Warsaw to Vilna, posing as a non-Jew, travelling with false papers and during November 1941 he returned to Warsaw to inform the Jews about the slaughter at Vilna.

Adam Czerniakow summoned the leading members of the Underground to hear Grabowski’s message: Zivia Lubetkin later recalled. “It was in the evening, there was no electricity, and Heniek told his story.” The story Grabowski told was about Ponary. “For the first time,” Zivia Lubetkin recalled, “we heard that Jews of Vilna are being deported by the thousands and tens of thousands, and being killed, children and women.”

Yitzhak Zuckerman had also been summoned to hear Grabowski’s report. “I am from Vilna myself,” he later recalled. ”I was born in Vilna – in Vilna I left behind all my parents and relatives. And here he brought this tragic news from Vilna. While still a child I had played amongst the trees in Ponary, and here he spoke about Ponary.

My Vilna, the Jews of Vilna, were being killed in Ponary, my playground.” A final action on 21 – 22 December 1941 reduced the population of the Vilna ghetto to 12,000. Thus altogether 25,000 to 30,000 Vilna Jews were killed. The slaughter had been prolonged over several months, being carried out by a permanent execution commando at a permanent killing establishment.

Thus, it provided a prototype for the death camps in Poland and the prolonged resettlement actions of 1942 -43. The Hauptsturmfuhrer of the SD in charge of this operation Martin Weiss, was to make a dramatic reappearance after the war when, after concealing himself for more than four years as a house-porter in Ochsenfurt, he was convicted by the Wurzburg Schwurgericht in February 1950 of 30,000 murders and sentenced to life imprisonment.

On 5 April 1943 three hundred Jews from the ghettos of Sol and Smorgon, in Macedonia, were deported to Ponary. They had been told that they were to be “resettled” in the Kovno ghetto. On reaching Ponary they realised they had been deceived. That night, a fifteen year old Vilna schoolboy, Yitshok Rudashevski noted in his diary the story that reached Vilna within a few hours:

Like wild animals before dying, the people began in mortal despair to break the railway cars, they broke the little windows reinforced by strong wire. Hundreds were shot to death while running away. The railway line over a great distance is covered with corpses.”

All those Jews from Sol and Smorgon who survived the rail-side massacre of 5 April 1943 were shot in the pits at Ponary by the German and Lithuanian SS men.

A few hours later, five thousand more Jews reached Ponary, mostly young men from the ghettos of Swieciany and Ozmiana, whom the Gestapo feared might find a way of escaping from the ghettos in order to join the growing number of Jewish and Soviet partisans.

These five thousand were sent first to the Vilna ghetto. Then as with the Jews from Sol and Smorgon, they were sent on as if to the Kovno ghetto, “where there was more room.” Just outside Vilna their train came to a halt – they too had been brought to Ponary. Sensing the danger, these young men tried to break out of the freight cars and fought, with revolvers, knives and fists.

They were shot down in the cars themselves, and along the railway line. A few dozen managed to escape to Vilna- the rest were killed on the spot.

The Polish journalist W. Sakowicz, noted in his diary:

Bonfires burn near the station - They were kindled by policemen. Again a train from Vilna – they have arrived. The people were driven out from the carriages, and immediately a small batch was taken to the pit. The ones with poorer clothes on weren’t even undressed.

They were driven to the pit, and shooting began immediately.

Another batch of people were standing nearby and, on seeing what had happened to their nearest, began to yell. Some started running. A little lagging behind the others with her hair dishevelled, a woman is running pressing her child to her breast. The woman is chased after by a policeman, he smashes her head in with the rifle butt, the woman collapses

The policeman seizes the child by its leg, drags it to the pit. Among those participating in the Ponary massacre of 5 April 1943 was SS Sergeant Wille. “While shooting,” noted a German Security Police report, Wille “was attacked by a Jew” and wounded “by two knife blows in the back and one blow in the head.”

He was immediately taken to the military hospital in Vilna. “His life is out of danger,” the report continued, and added: “A Lithuanian policeman was fired at while some fifty Jews tried to escape, and he is badly wounded.” In Vilna the poet Shmerl Kaczerginski was standing not far from the ghetto gate. “I saw a young fellow sneaking in,” he later recalled, “bloody, weary, disappearing quickly into a doorway.”

In the security of someone’s home, the young man then pulled of his clothes, washed away the blood, tied up his wounded shoulder and whispered to those who had crowded around him: “I come from Ponary.” Kaczerginski added- “We were petrified. The young man told them: “Everyone – everyone was shot!” The tears rolled down his face. “Who”, he was asked. Did he mean the four thousand who were being sent to Kovno? Yes.”

In 1944 at the Ponary execution site Szloma Gol was among seventy Jews, and ten Russian prisoners –of – war suspected of being Jewish, who as members of a “Blobel Kommando” , had to dig up and then burn the bodies of those who had been murdered during the years 1941 – 1943.

Each night the eighty prisoners were forced to sleep in a deep pit to which the only access was by a ladder drawn up each evening. Each morning, chained at the ankles and waist, they were put to work to dig up and burn tens of thousands of corpses. These eighty prisoners were supervised by thirty Lithuanian and German guards and fifty SS men. Their guards were armed with pistols, daggers, and automatic guns – one armed guard for each chained prisoner.

Two and a half years later Szloma Gol recalled how, between the end of September 1943, when their work began, and April 1944:

We dug up altogether 68,000 corpses. I know this because two of the Jews in the pit with us were ordered by the Germans to keep count of the bodies – that was their sole job. The bodies were mixed, Jews, Polish priests, Russian prisoners-of –war. Amongst those that I dug up I found my own brother. I found his identification papers on him. He had been dead two years when I dug him up, because I know that he was in a batch of 10,000 Jews from the Vilna ghetto who were shot in September 1941.

The Jews worked in chains, anyone removing the chains, they were warned, would be hanged. As they worked, the guards beat and stabbed them. “I was once knocked senseless on to the pile of bodies,” Szloma Gol recalled, “and could not get up, but my companions took me off the pile.”

Then I went sick.” Prisoners were allowed to go sick for two days, staying in the pit while the others worked. On the third day, if they were still too sick to work, they would be shot. Szloma Gol managed to return to work. As the digging up and burning of the bodies proceeded, eleven of the eighty Jews were shot by the guards – sadistic acts which gratified the killers, and were intended to terrorise and cow the prisoners.

But inside the pit, a desperate plan of escape was being put into effect – the digging of a tunnel from the bottom of the pit to a point beyond the camp wire, at the edge of the Ponary woods.

While the tunnel was still being dug, a Czech SS man alerted the Jews to their imminent execution, “They are going to shoot you soon”, he told them, and “they are going to shoot me too, and put us all on the pile. Get out if you can, but not while I am on guard.”

One of the sixty-nine surviving prisoners, Isaac Dogim, took the lead on organising the escape. Dogim had been placing the corpses in layers on the pyre one day, when he recognised his wife, his three sisters and his three nieces.

All the bodies were decomposed, he recognised his wife by the medallion which he had given her on their wedding day. Another prisoner, Yudi Farber, who had been a civil engineer before the war, joined in the preparations for the escape.

On 15 April 1944 the prisoners in the pit at Ponary made their bid for freedom. Forty of them managed to get through the tunnel, but a guard, alerted by the sound of footsteps on the pine branches, opened fire.

In the ensuing chase twenty- five Jews were shot, but fifteen managed to reach the woods, later most of them joined the partisans in the distant Rudniki forest. Five days after the escape, the remaining twenty-nine prisoners were shot.

Sources: The Final Solution by G. Reitlinger – Vallentine Mitchell &Co Ltd 1953 . The Holocaust – The Jewish Tragedy by Sir Martin Gilbert published by Collins London 1986 Those were the Days – by Ernst Klee, Willi Dressen, Volker Reiss, published by Hamish Hamilton London 1991 USHMM "Hidden History of the Kovno Ghetto" Bulfinch Press 1997. Ghetto Fighters House

Copyright. Chris Webb HEART 2007

|