Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Einsatzgrϋppen

Einsatz Group A Einsatz Group B Einsatz Group C Einsatz Group D Babi Yar Articles Einsatz Leaders Einsatzgruppen Operational Situational Reports [ OSR's #8 - #195 ]

| |||||||

Einsatzgruppen AExecutions in Fort Vll and Fort lX

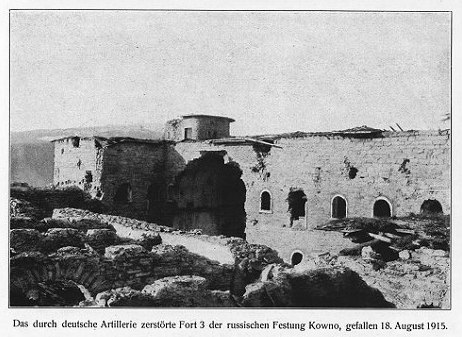

Kovno was surrounded by a series of forts built in Czarist times to protect the city from German invasion. Between the wars these forts were used as prisons for criminals serving long sentences. During the German occupation, 1941 – 1944, the forts were used as both prisons and execution sites, particularly of the Jews of Kovno.

Read more about Kovno [Here]

The Seventh and Ninth Forts were close to the Ghetto – in time they became widely known as symbols of mass murder, as did the Babi Yar ravine in Kiev, the Rumbuli forest near Riga and the ditches of Ponary near Vilna.

Report of a medical orderly:

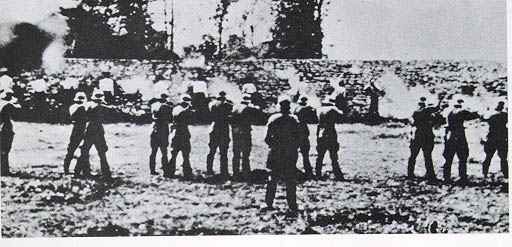

About 150 m from my quarters there was a fort. Looking at the map I think it must have been Fort Vll, although up to now I had always thought that there was only one fort in Kovno. From our quarters my mates and I heard shots during the night. The next day and the days after that we went to investigate the matter, climbed on to the ramparts of the fort and saw a crowd of people below us guarded by armed SS or SD men.

The guards were all German – there were no Lithuanians. During one of these visits the technical inspector, whose name I do not remember, took these pictures with his camera. At that time we didn’t see any shootings during the day. We heard that these shootings took place at night. During the day the people – men, women and children – were brought from Kovno to this fort. If I remember correctly they were all Jews, at least they were the only ones that were talked about.

The bodies were thrown into a large crater that had a diameter of 15m and was, I should think, about 3-4 meters deep. Each layer of bodies was covered with chloride of lime. People used to say that the next group of Jews always had to throw the last lot to be shot into the crater and cover them with sand. I only went up to this crater once but couldn’t see any bodies because everything was covered with sand.

On one of my wanderings through the fort I lost my way as I was not sure where the entrances were. On this occasion a Jewish woman of about thirty ran across my path. She had been shot through both cheeks and the wounds had swollen up considerably. Seeing the red - cross on my armband she begged me for a bandage, which I wanted to give her.

I was just busy getting the pack of dressings I’d brought with me out of my jacket when an SS or SD guard with a rifle came up to me and told me to make myself scarce, saying that the Jewess had no further need of a pack of dressings. The Jewish woman was then pushed back by the uniformed German.

I was very shaken by this experience and told my colleagues about it – they were shaken too. It would have been pointless and dangerous for me to have disobeyed the SS man – they were very ruthless. He threatened to shoot me down if I didn’t get on my way. During my visits to the fort I estimate I saw at least 2,000 people of different ages, both male and female, who were all destined to be shot and indeed certainly were.

Following a round-up of Kovno’s Jews on 28 October 1941 in Democracy Square and selection by SS man Rauca, Jews were separated into two columns, left and right. Right was death, left was life, recalled Leon Bauminger. Thos Kovno Jews who were sent by Rauca to the right could still not believe that they really been marked out for death. “That morning in Democracy Square,” a Lithuanian doctor, Helen Kutorgene, noted in her diary, “nobody suspected that a bitter fate awaited them. They thought that they were being moved to other apartments.”

They were indeed taken not to the Ninth Fort but to the houses of the small ghetto. On the night of 29 October Dr Peretz has recalled, everyone sent to the small ghetto “was trying to find a better place, there was better order, because they thought they would stay there.”

Then, at four in the morning, all those in the small ghetto were ordered to assemble again. It was still dark. But with the dawn a rumour began, that prisoners had been digging “deep ditches” at the Ninth Fort, and by the time those who had been sent to the small ghetto were led away towards the fort, Helen Kutorgene noted in her diary, “it was already clear to everybody that this was death.”

Dr Kutorgene added that once the Jews whom Rauca had sent to the right realised where they were being sent:

"They broke out crying, wailing and screaming. Some tried to escape on the way there but they were shot dead. Many bodies remained in the fields. At the fort the condemned were stripped of their clothes and in groups of three hundred they were forced into ditches. First they threw in the children. The women were shot at the edge of the ditch, after that it was the turn of the men.

Many were covered while they were still alive. All the men doing the shooting were drunk. I was told all this by an acquaintance who heard it from a German soldier, an eye-witness, who wrote to his Catholic wife. “Yesterday I became convinced that there is no God. If there were, he would not allow such things to happen.”

The massacre had been carried out by German SS men and Lithuanian police. On return from the killing, one of the Lithuanians boasted – as a Jew Alter Galperin later recalled – “that he had dragged small Jewish children by the hair, stabbing them with the edge of his bayonet, and throwing them half alive into pits.” "The smallest children “he just threw into the pit alive, because to kill all of them first is too much work.”

One of the few survivors was a twelve year- old boy. It was only when he managed to return to the main ghetto on 30 October that those in the ghetto realised the full horror. Avraham Golub, an assistant in the Jewish Council later recalled how the boy, “covered in dirt and smeared with blood”, stumbled into the Council office.

Golub’s account continued:

He reported how everyone was forced to strip and made to march in groups of one hundred to the edge of freshly dug pits. The guards fired on each group as they stepped forward. Some were only wounded but they too fell into the deep pits and were covered with a layer of earth. The boy was with his mother, was covered by her, and so was not hit by the bullets. The boy and his mother were destined to be the second layer of bodies from the top of the grave.

His mother had embraced him and covered him. She bent forward and fell into the pit with him, so that he was not suffocated by the layer of earth poured on top. When it was dark, the boy slowly moved to the edge of the pit. With great effort he pushed away the bodies around him and crawled out. There he was able to see that the earth which covered the pit was moving, meaning that many others were still alive in the pit but were unable to save themselves. Under darkness he escaped back to the ghetto and was later smuggled out. No one knows if he is alive today.

A few women also managed to survive the massacre. “Some tried to escape from the transport, Aharon Peretz later recalled. I was asked to go to a neighbouring house, where there were women with “dum-dum” bullets in their bodies. The number of those murdered was recorded, once again, in the precise statistics of the Einsatzkommando:

Jews from the Greater Reich were also sent to Kovno but only a small percentage were admitted to the ghetto. Most of them went direct to the Ninth Fort where they were kept some days prior to being shot in the execution pits. A Lithuanian guard testified before the Russian State Commission of 1945 that there were two executions of 3,000 – 4,000 Reich Jews on 10 December and 14 December 1941.

A Kovno ghetto survivor testified that in January or February 1942, the Prague and Vienna Jews in the Ninth Fort rebelled before being shot. The Reich Jews, who began arriving in Kovno from Berlin, Hamburg, Dusseldorf and Prague at the end of November 1941, numbered 15,000 according to this witness, but the portion admitted to the ghetto was determined by the number of native Kovno Jews who had been shot – apparently 5,000.

Dr Aahron Peretz was an eye-witness in Kovno, and he later recalled how, as the deportees were being led along the road which went past the ghetto to the Ninth Fort, they could be heard asking the guards, “Is the camp still far?” They had been told they were being sent to a work-camp. But Peretz added, “We know where the road led. It led to the Ninth Fort, to the prepared pits.”

But first the Jews from Germany were kept for three days in underground cellars with ice- covered walls, and without food or drink. Only then frozen and starving were they ordered to undress, taken to the pits and shot.

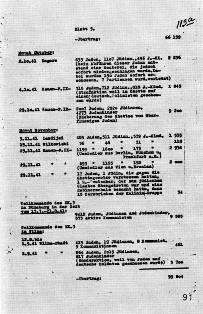

The killing of these deportees was recorded with the usual SS efficiency:

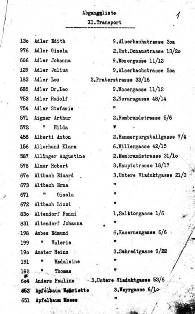

On 25 November 1941 1,159 Jews, 1600 Jewesses and 175 Jewish children , settlers from Berlin, Munich and Frankfurt am Main – and four days later 693 Jewish men , 1,155 Jewesses and 152 Jewish children, settlers from Vienna and Breslau. Diary Entry of Avraham Tory following a meeting with Captain Vassilenko regarding the escape from the Ninth Fort in December 1943

The Ninth Fort

The Ninth Fort, a military fortress near Kovno, for a long term, served as part of the Kovno prison for dangerous criminals. During the Nazi occupation it became a place of torture and mass executions. In secret the Nazis called it Vernichtungsstelle Nr 2 – Extermination place number 2. Here were murdered some 25,000 of Kovno’s Jews, as well as 15,000 Jews deported from the Greater Reich, thousands of Jewish Prisoners – of – War who had served in the Red Army, and many other Jews.

Single and mass arrests, as well as “Aktions” in the Ghetto, almost always ended with a “death march” to the Ninth Fort, which in a way, completed the area of the Ghetto and became an integral part of it. A road three to four kilometres long led uphill from the Ghetto to the Fort, a special road called by the Ghetto inmates the Via Dolorosa. The murderers called it the Way to Heaven (Der Weg zum Himmel- Fahrt).

Before their execution, the detainees were incarcerated in underground cells known as “casements” in damp, darkness, and fear. There, people fought with one another for a brighter corner in the cells, for a piece of a straw mattress, for a scrap of food, or for a crumb of bread. There, Jews were shackled in iron chains, harnessed to ploughs in place of horses, forced to dig into peat-pits inside the fort, and often whipped to death. There, one soon lost one’s own – there, life turned into senseless pain, after which death came as redemption.

Keidan a father of four children was incarcerated at the Fort and tortured there for five months. With others he stood naked in the pit awaiting execution, miraculously escaped from the Fort. He was the first to bring an authentic report from the Hell on Earth. In fifteen mass pits, some 45,000 innocent victims found their awful burial, 3,000 in each pit. Thousands of Red Army Prisoners- of –War, all Jews were separated from the other Soviet Prisoners – of – War and were systematically massacred at the Ninth Fort.

As long as German troops went on with their “March to the East”, the digging of new mass graves at the Fort continued. When the German advance was blocked in July 1943, there was no more digging of mass graves. And when the Germans were forced to retreat, they hurried to erase all traces of their crimes.

In August 1943 the Kovno Gestapo received orders from Berlin to eradicate the mass graves – to exhume the corpses and to burn them. This was to be carried out by the end of January 1944, when the German retreat from the Baltic States was foreseen. The carrying out of this order was imposed upon seventy-five Jews who were already imprisoned at the Fort, among them Ghetto inmates who had been seized in the Ghetto and brought to the Fort, Red Army Prisoners –of – War, and youngsters from the Ghetto, who had been caught on their way to join partisans in the forest.

Eleven of the seventy-five declared at the outset they were ill, and not capable of doing the job. The Gestapo murdered them by injections of poison. The remaining sixty –four, sixty men and four women formed a labour squad. All of them, apart from one Polish woman, were Jews.

The work started in September 1943. Fiery beacons started to rise from the Fort, crowned by clouds of smoke. The labour squad had begun to carry out the German order. The sixty-four were divided into four groups, each of which carried out a part of the job. One group “the diggers” had to dig out the dead corpses – to scrape off the upper layer of the earth from the pits, and then, with spades, remove the first layers of the corpses. This group had to go down into the pit by ladder and, using pitchforks, toss the remaining bodies up to the surface.

The German supervisors used to make cynical remarks such as “stick the pitchfork in the belly of that disgusting Jew” or “toss up that Jewish woman – that Sarah – by digging your pitchfork into her hair,” or similar pearls. When the corpses were brought up, the gold teeth had to be extracted, all rings and bracelets removed, and searches made for gold and jewels in the rotting garments of the dead.

Then all valuables had to be cleaned and polished and handed over to the German supervisors. Most of the corpses were half or totally decayed, but some were well preserved. More than once, the diggers recognised their own acquaintances. On one occasion, a digger recognised his brother. Once the belly of a woman in her last month of pregnancy cracked in the terrible heat of the pyre, and from inside her burst a small baby’s body. The Jewish prisoners were stunned. Even the Nazi guards were astonished.

The corpses of the Lithuanian Jews were naked, and lying on one another lengthways and crossways. Only rarely were bullet holes to be found. From the expressions on their faces and from the way they were lying, it could be seen that most of them had choked to death in the pits. The bodies of women with babies in their arms were also found.

The corpses of German, Austrian, Czechoslovakian, and other Jews were found in separate graves. These were clothed and bore all the marks of a bitter struggle. This confirmed rumours which had spread in the Ghetto during the “Great Actions” of 1941, that these Jews had fought against their murderers and had not undressed before being murdered. At the time some of the Gestapo men had returned from the Fort badly wounded and bleeding. After the corpses had been brought out of the pits by the diggers, the members of the second group, “porters,” piled the bodies on special wooden pallets, counted them in the presence of a Nazi supervisor, and took them to the pyres.

There the third group, the “firemen” were at work, headed by an expert on burning – the “Brandmeister.” This group had to prepare the pyre once every twenty-four hours, as follows:

In the courtyard of the Fort, not far from the pits, they would lay out a long row of logs, put a row of bodies on it, then lay another row of logs on top of the bodies and another row of bodies on the second pile of logs. The daily quota was fixed at three hundred bodies.

To make it easier to light the fire, kerosene was poured into holes dug in the ground, as well as over the corpses themselves. On either side were narrow trenches, into which ran the fat of the burning corpses. The firemen had to make sure the fire did not go out in the middle of burning the corpses. If as much as a hair was left unburned they were liable to pay for it with their own lives.

After each fire there remained heaps of ashes and bones, which were pounded in huge mortars. This “flour” was flung into the air, or dug into the soil. The fourth group was engaged on various tasks in the courtyard, the kitchen etc. One of this fourth group was Dr. Portnoy. He had previously worked with a German pastor by the name of Pollet, in editing a German – Lithuanian dictionary.

One day Portnoy disappeared without a trace. The pastor had considerable influence with the Kovno Gestapo, but not enough to bring back his Jewish assistant. Portnoy was supposed to be dead, but finally he turned up among the sixty-four and served as their doctor.

The SS men at the Fort carefully watched every move made by the Jewish workers, to make sure that not a single corpse was left in any of the pits. It was absolutely forbidden to fill in with earth any pit from which the bodies had been removed. The workers could expect to be beaten murderously if an unconsumed limb was found in the ashes when one of the pyres was put out.

High Gestapo officers, and even Nazi generals, used to visit the Fort and watch the work. Some of them told the Jews that they were disposing of the victims of the Bolshevik terror; others claimed that the bodies were those of Communists, the blood –and- soul enemies of all humanity, and that it was a good deed to liberate the world from this peril.

All of them tried to convince the Jews that no harm would be done to them, that after they had completed this work they would be transferred elsewhere, as there was more than enough work for them. This consoled the Jews very little – on the contrary, it made them nervous. During one such visit, one of the Jews blurted out a bitter remark – when his pitchfork lifted up, from the pit, the corpse of a child, he cried out, “This is a dangerous Bolshevik, a great threat to mankind. Take him to the pyre. Burn his bones!”

The permanent SS supervisors at the Fort said more than once that the fate of the workers had already been decided, and that not one of them would ever leave the Fort. Witnesses of this kind cannot remain alive. The four work groups were ordered to speed up their work. The murderers had grown nervous al

l of a sudden. Their dead victims had began to bother them, and they were in a hurry to destroy all traces of their crimes.

In general, the life of the prisoners did not change – they were forced to work in chains and subjected to the whims and caprices of their torturers. However, to increase productivity, SS Captain Gratt, the Fort Commandant, ordered that the prisoners be allowed to eat their fill, and even supplied them with tobacco and alcohol occasionally, to help them withstand the dreadful stench from the pits.

They were provided with pillows and blankets from the Ghetto, and three Jewish women were brought from the Ghetto to satisfy their sexual needs. But the prisoners did not delude themselves, they knew with absolute certainty that as soon as they had finished their dreadful task they would also be burned in the final conflagration.

Every pit that was emptied, every pyre that was put out, brought them closer to their own extermination. Before starting to born the corpses, the Germans erected special walls of white sheeting, to prevent people from looking into the Fort from outside, and thus to conceal the digging up of the mass graves and the burning of corpses.

It was impossible. However, to conceal the flames and the thick smoke that came from the Fort every twenty-four hours, it was impossible to suppress the terrible stench from the re-opened pits, which was carried by the wind for many kilometres all around. “Hell is burning” – so the peasants of the surrounding villages whispered to themselves while watching the glow of the flaming pyres.

“Our brothers are burning, our own blood is burning” – so observed the Jews, helpless and imprisoned in the Ghetto, a few kilometres away, in the valley. The red strip in the sky, the new crown on the Fort, whispered quietly the word “revenge.” Not one of the sixty-four prisoners believed he would remain alive. Yet a spark of hope nevertheless flickered in their hearts. Only a few, however, dared to think of rescue. They were reminded morning and evening, day and night, that nobody had ever escaped from the Ninth Fort.

In October 1943 a new prisoner, Captain Kolia Vassilenko was brought to the Fort from the Soviet prisoner-of –war camp near Kalvaria. At the camp, Vassilenko had been regarded as a Russian until he was compelled to go to the bathhouse, and was discovered to be a Jew.

From the first day of his detention at the Fort he made up his mind to escape. While at work he studied the internal and external arrangements of the Fort, observing the methods of guarding the place and the housing conditions of the guards. With the utmost secrecy, he gathered round him initially a small group, which he imbued with his own idea of escape and flight.

The original plan was to dig a tunnel that would be a kilometre long, and to go out to freedom through it. For several weeks the prisoners dug this tunnel with unskilled hands and without tools, digging beneath subterranean structures of the Fort.

They carried the earth out in their pockets and threw it into the pits. They succeeded in hiding their excavations from the guards, and also from their fellow prisoners. It seemed as though their plan would be successful, until they reached a huge rock below the surface and had to give up, filling the tunnel once again with earth, after all the toil and effort with which they had dug it.

In spite of this setback, however, Vassilenko and his comrades did not despair and sought other methods of escape. A second plan was to use gold and valuables taken from the corpses to bribe the SS guards, and to escape with them. At that time, however, not one of the SS men thought of deserting or of bribes.

The plan could not be carried out because the guards had already stolen so many valuables that more bribes would not induce them to take such a risk, and the danger to the lives of the guards was not so near or so threatening as it was for the prisoners. Besides, according to this plan, only a few of the prisoners would be able to escape.

The third plan was to disarm the two supervisors who came every evening to confine the Jews for the night in the underground cells, kill them quietly, steal their uniforms, kill the other two guards in the courtyard, infiltrate the guardroom, kill the guards on duty there, take gold and valuables from the safe, arm themselves, and then take the truck that always stood in the courtyard, kill the guards at the main tower, and drive away.

The main difficulty of this plan was to break into the guardroom, entrance to which required a password that no outsider knew. To break in by force was dangerous because there was a complicated signal system between the commander of the fort, the central prison, the Gestapo headquarters, the police, and the military. Before someone could get into the guardroom the whole Fort would be flooded with reinforcements and surrounded by an impenetrable cordon of Gestapo and SS men. This plan was therefore rejected. The plan finally decided on was this:

The prisoners proposed to prepare a key to one of the storerooms above the underground cell in which the group was locked up at night. From this store, a door led to a tunnel in the courtyard of the Fort. From this tunnel it would be necessary to dig a second one to the outer wall of the citadel. Within the Fort there were small workshops which supplied the Forts internal needs. A few Jews worked in these workshops – it was they who prepared the key. The hardest thing was to open the thick steel door to the tunnel. For this they had no tools.

It was a daring plan, but their situation was so desperate that they resolved to try and carry it out. A key was prepared, and the unused storeroom facing their quarters was opened. Every day, two men of the group remained behind, claiming to be ill – according to the rules, only two of the group were allowed to be ill and absent at any one time. One of them equipped with a penknife which had been found in the rotting clothes of a corpse and with a small hand-drill removed from a workshop, drilled through the heavy steel door, while the other kept watch.

Gradually they made holes through the door and sawed through the steel between the holes. They also worked in the evenings and used to sing songs and joke at the top of their voices to cover the sound of drilling. They were not discovered in their dangerous work, and were not interfered with even when they sang Soviet songs. After each drilling, they would conceal the door behind a pile of rags.

After weeks of strenuous labour, the hole in the steel door was finally made. It was thirty to forty centimetres, which was just enough for a person to pass through. The day for the flight was finally fixed for 25 December 1943, Christmas day.

All preparations were completed, and partial rehearsals were begun. The tunnels through which the escaping prisoners had to pass were still blocked, however, with wooden beams that had to be removed. They complained that the wood they received for the pyres was wet and would not burn, either in the kitchen or on the pyres. They therefore asked permission to take dry wood from the tunnels. The Fort commandant suspected nothing and gave permission, and so the last obstacle was eliminated.

As the agreed date approached, the prisoners rehearsed their escape plan again and again, and their tension increased. The mere scale of the plan was enough to terrify them. They feared that a single un-cautious step would destroy all their preparations and put them in the hands of the murderers.

They were also afraid that they would be replaced before 25 December by a different team of workers, and thus be killed before they could carry out their plan. Each of the four groups had its own commander – details were given to these leaders, who were provided with full and detailed instructions.

They were warned that any incautious step might cause a catastrophe. Not a word was to be said. Not a step was to be taken without orders. Not the slightest sign of excitement was to be shown. Finally the long-awaited 25 December arrived. Only half –a day’s work had to be done, in honour of Christmas day, SS Captain Gratt addressed the sixty-four prisoners, and expressed his satisfaction at the tempo of the work.

Since the Jews were labouring so diligently he said he would try to improve the conditions under which they lived. Each of them would receive schnapps and cigarettes in honour of the holiday. They would not work for the two days of Christmas. Gratt wanted them to rest properly, so they would return to work the following Monday refreshed and with renewed strength.

Once again, he promised that not a hair of their heads would fall to the ground, and that when this work was over they would be given more work somewhere else. One of the workers answered the captain on behalf of all of them, thanking him for his kind attitude and for the schnapps and tobacco. He wished the Fort commander “a quiet holiday.”

The Jews gave the drink and tobacco to the guards to make them get even more drunk, so they would not notice the excitement and nervousness of the prisoners. Tension increased every moment. By 7pm the workers were all in the underground structures, impatiently awaiting the arrival of the guards who would lock them in for the night and then go out on guard again as usual in the courtyard in front of the building.

About half an hour after the door was locked, the lights would be put out, to be put on again only at 5 a.m. During those hours of darkness the prisoners hoped to carry out their plan. But the guards did not arrive at 7pm as usual. They did not lock the workers in or put the lights out. Nobody understood what had happened – all feared the worst.

A full hour passed in tense expectation – precisely at 8pm, the two warders appeared and locked the doors. It turned out that in honour of Christmas they had wanted to give the Jewish prisoners some pleasure, and so had allowed their doors to remain unlocked. Half an hour later the lights were put out as usual and the guards left the building. The prisoners waited a little longer, and then began carrying out their plans.

First they broke through the thin layer of iron over the steel door, which had been sawed through in advance. Then one of them climbed through the hole into the corridor and, using the keys that had been prepared, swiftly opened the doors of all the subterranean cells.

The corridor floor and the iron stairs of the abandoned storeroom were immediately covered with blankets to deaden any noise of their movements. All the prisoners emerged into the corridor in absolute silence and assembled in their groups, two by two. The final instructions were given – once more the leaders warned them that any hesitant or wrong step by a single one of them might cause the death of all.

Any breach of discipline would be settled on the spot by a knife-blade in the heart. And so they mounted the steps, group by group, one after the other. They opened the storeroom with a key and reached the entry through the steel door. Vassilenko and another of the first group stood on either side of the door, ensuring that everything was done properly.

Without a word they all passed as planned through the hole and entered the tunnel. There the groups formed up again and slowly moved forward to the moat in the courtyard. There they crossed the moat, entered the second tunnel, passed through that to another moat, and reached the outer wall of the Fort.

Beside the wall they put up a screen of white sheets they had brought with them, thus concealing all movement around the ladders they were lowering over the wall, which was six meters high. Each group was accompanied all the way by the leader of the next group, who then returned and led his own men, and the leader of the following group.

After they had all climbed over the wall and reached freedom, they were followed by Captain Vassilenko. Vassilenko and a number of the escapees made their way to Kovno Ghetto where he gave details of the escape and how in1943 how the Germans carried out the murder of the family of Chief Rabbi Shapiro, which he had heard about.

Early in 1943 the rabbi’s son, Dr Chaim Nachman Shapiro – a university lecturer – had been taken to the fortress with his wife, their fifteen –year old son, and his old mother, the rabbi’s widow. They were all shot that same day and their bodies flung into the flames.

The fugitives also brought with them evidence and materials they had collected in and around the graves during the excavations. “Let them be given to relatives in the Ghetto, to let them know for whom there is no point in waiting any longer.”

Vassilenko told us – the group had also brought with them the gold teeth of some of the slain – the gold weighed a quarter of a kilogram. The other groups had also taken documents and valuables with them.

Sources: The Final Solution by G. Reitlinger – Vallentine Mitchell &Co Ltd 1953 . The Holocaust – The Jewish Tragedy by Sir Martin Gilbert published by Collins London 1986 Those were the Days – by Ernst Klee, Willi Dressen, Volker Reiss, published by Hamish Hamilton London 1991 Surviving the Holocaust – The Kovno Ghetto Diary by Avraham Tory, published by Pimlico, Harvard University Press 1990.

Copyright. Chris Webb HEART 2007

|