Vienna Can a city come to terms with its past? Carmelo Lisciotto

Anti-Semitism in Vienna There are many reminders of Jewish life in Austria, and especially in Vienna. In 2001, the General Settlement Fund for Victims of National Socialism was established on the basis of the Washington Agreement in order to enable a comprehensive resolution to open questions of compensation for victims of National Socialism on the territory of the present day Republic of Austria. Both institutions pursue a common goal: The recognition of Austria's special responsibility towards the victims of the National Socialist regime. The Jewish renaissance in Vienna began in 1848 and lasted until the start of World War II. Jews were granted civil rights, partially due to their participation in the 1848 civil war and were allowed to form their own autonomous religious community, which served the Jewish population of Vienna and of Austria as well. Vienna also became a center of the Haskalah, a movement toward secular enlightenment. The contribution of the city's Jews to music, literature, visual arts, and theater at the end of the nineteenth century and in the early decades of the twentieth was immense. The idea of establishing the Secession art association, and constructing its magnificent art nouveau gallery, was born in Berta Zuckerkandl's salon. Composers such as Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schönberg, and Alexander Zelimsky were leading figures in Vienna's musical life. The list of Viennese writers and journalists of Jewish origin is long and distinguished, and accounts for a major part of twentieth-century Austrian literature. Arthur Schnitzler, Peter Altenberg, Karl Kraus, Franz Werfel, Stefan Zweig, Franz Kafka, Friedrich Torberg, Hans Weigel, Elias Canetti, Jura Soyfer, Hilde Spiel - each name stands for a specific chapter in Austrian literary history. The birth of Nazism caused yet another dramatic rupture in the historical development of the city in general and its Jewish community in particular. Before 1938, the Jewish community was one of the largest in Europe numbering some 185,000. After 1945, a small but active Jewish community reestablished itself again; today, it comprises about 7,000 members – of the 10,000 to 12,000 Jews who live in Vienna at present.

During the past two decades, the city has stepped up efforts to face up to the history of Jews in Vienna, including both positive and negative aspects, and to reexamine Vienna’s Jewish heritage. In addition to the Jewish institutions that have sprung up over the last few years – thanks to the support of the City of Vienna – a number of museums and memorials evoke the city’s Jewish heritage. Is Austria, by taking such concrete measures, finally coming to terms with its past? (Let's examine)

Jewish Vienna Today The traditional religious center of Jewish life in Vienna is the Vienna City Temple. It is the only synagogue that survived the pogrom of November 1938. The building complex at Seitenstettengasse 4 houses not only the synagogue, but also the offices of the Vienna Jewish Community, the Vienna Chief Rabbi, the editorial offices of the official community newspaper Die Gemeinde, the Jewish community center which stages various events and the Library of the Jewish Museum.

Near Seitenstettengasse, in the heart of the so-called “Bermuda Triangle” – a popular bar and restaurant hotspot – there is yet another focal point on Judenplatz which confronts visitors with Jewish life past and present: the Shoah Memorial and the Judenplatz Museum, opened in fall 2000.

On the way from Seitenstettengasse to Judenplatz, you pass the Old City Hall (Altes Rathaus – Wipplingerstrasse 8, 1010 Wien), where the Documentation Archives of the Austrian Resistance are located; they document the crimes of National Socialism and include important materials about right-wing extremist and racist developments in Austria.

Long pursued half-heartedly, the issue of compensation and restitution of the victims of National Socialism has been addressed at various levels in the past decade. The appointment of the Austrian Historical Commission in 1998 at last marked the creation of a body to scientifically and comprehensively investigate the whole complex of expropriation of Jewish property in all areas of business and society. On January 17, 2001 the Republic of Austria committed itself to reparations under the Washington Agreement that compensate for property and assets that were stolen during the Nazi era. Under the Austrian General Settlement Fund Law (“Entschädigungsfondsgesetz”), a general fund was set up in 2001 to comprehensively address open claims regarding compensation for victims of National Socialism.

Jewish Vienna Then The signs of Anti-Semitism's approaching collapse are increasing:

Vienna is still the stronghold of anti-Semitism, and Dr. Carl Lueger, the Burgomaster, its most notorious exponent in Europe. For nearly three years the administration of the Austrian capital has now been in the hands of the anti-Semitic party, but the signs of its approaching collapse are increasing.

Upon the head of Dr. Lueger, that greatly overestimated man, the shadows of evening are already beginning to descend. Only a year ago the interesting face and slender figure of "handsome Carl" were to be seen in a hundred representations of every kind; women displayed his picture in brooches and medallions, every barrel organ in the suburban courts and alleys, and every band in the Prater beer gardens, played the "Lueger March" amid frantic applause. Today Lueger's portrait is hardly anywhere to be seen, the notes of the "Lueger March" have ceased to assail unwilling ears, and the barrel organs have taken out the Lueger plate. In office anti-Semitism still is, but on the minds of the befooled million a light has begun to break. Lueger's lieutenants--Schneider, Gregorig, Gessmann and Vergani---feel this change even more than their leader himself. Indeed the Christian Social leaders, who on every opportunity were hailed by the multitude, now feel no longer even safe; their houses have to be watched day and night by the police. Now the people's leaders have to be protected from the people by the police. To any critical observer it has been clear that the anti-Semitic regime could not last long. It is a peculiarity of this singular movement that it soon works itself out. Germany first started it. But the movement makes no progress there; in fact, it is now less than it was ten years ago.

But from Germany anti-Semitism, nevertheless, made its way first to Russia, her Polish provinces, and to Rumania. There the ground had been well prepared as even before that time society and legislation had been anything but favorable to the Jewish race. It had always held an exceptional position, and been tolerated only. In those countries, the anti-Semitic doctrine resulted merely in violent but isolated outbreaks of the mob against the Jews. Such fits repeated twice or thrice resulted in an influx of pauper Jews into England and America; but for about ten years little or nothing has been heard out of this movement.

Boycotting the Jews:

Consequently the watchword constantly given to the befooled multitude was: "Don't buy of Jews, don't read Jewish newspapers!" Of the million and a half of inhabitants of this capital, about 120,000 are Jews. But of the 4,000 physicians half are Jews, and of something like 1,000 lawyers, some 650 belong to what Lord Beaconsfield called "The superior race"!

There was a superabundance of the elements with which to excite the envy and all the low instincts of the lower classes, and besides that the anti-Semites appeared under the well sounding and enticing name of "Christian Socialism." The oppressed were promised help and salvation. It is, however, true that the large, well organized Social Democratic party, the only self-reliant and enlightened party in Austria, was not to be misled and corrupted by the reactionary demagogues. But the mass of the lower middle class, which is badly off, and which is in a transitional economic condition, the small tradesmen, who daily receive new wounds from capitalistic industry, the badly paid lower officials, the great army of servants and petty folk adopted the anti-Semitic doctrine with fiery zeal. These people have the franchise, but the Social Democratic workers have not. When the elections came, the anti-Semites were victorious, as they desired to be. Their first act after obtaining the upper hand was to cut out the municipal budget of 15,000 florins an item of the 9,000 florins for school requisites for poor children. The items for building new schools, for the supply of drinking water, for almshouses, for the feeding and nursing of the sick poor were also considerably reduced. Now we are threatened with reductions in the salaries of the teachers, who are already poor enough. Workmen and teachers are refused the use of the rooms in the Town Hall in which they used to hold their meetings. The Jewish shorthand writers to the Diet have been dismissed. Jews cannot get places in the municipal administration, and they are excluded from supplying goods to the municipality, from building, and doing other municipal work. The Vienna Volunteer First Aid Society, a model philanthropic institution, which has served most towns in Europe as an example, was refused the customary modest annual subvention of somewhat more than 5,000 florins because most of the doctors connected with it were Jews--although they gave their services gratis! On the other hand, the Town Council has voted some 250,000 florins for churches, conventual schools and church societies. It is, in short, a struggle against education and culture that this remarkable party which calls itself Christian Social has inscribed on its banner.

- New-York Tribune Illustrated Supplement, [ dated 1889 ]

Jewish Vienna Today Judenplatz - Place of Remembrance

Since the erection of the Shoah Memorial and the establishment of a museum about medieval Jewry, Judenplatz has become a place of remembrance. Here you also find excavations of the medieval synagogue which can be accessed through the museum in the Misrachi House (Judenplatz 8, 1010 Wien). It contains documentation of the first Jewish settlements in the Middle Ages, which date back as far as the eleventh century, and of the first major expulsion of Jews in the years 1420-21, the so-called “Vienna Geserah.” The Jewish community was completely annihilated at that time – an anti-Jewish relief on the building at Judenplatz 2 (“Zum grossen Jordan“) serves as a reminder of this disastrous event. Austria’s Catholic cardinal Schönborn arranged for a memorial plaque to be placed on the house at Judenplatz 6, as a reminder of the anti-Jewish role of the Catholic Church; and in April 2001, the Jewish Community placed another memorial plaque, this one devoted to those who helped Jews during the Nazi era, on the so-called Misrachi House at Judenplatz 8.

The memory of National Socialism and the Holocaust is kept alive by the imposing memorial to victims of the Shoah by British artist Rachel Whiteread. The concrete cube depicts outwardly-facing library walls. It measures ten by seven meters, and is almost four meters high. On the ground around the memorial, the names of the places where 65,000 Austrian Jews were killed are inscribed. This memorial was erected by the City of Vienna at the initiative of Simon Wiesenthal and unveiled on October 25, 2000 after a long series of controversies. At the same time, the Judenplatz Museum, which documents the history of Vienna’s Jews in the Middle Ages, was opened.

The Judenplatz Museum is to be found in the building at Judenplatz 8, which also houses the orthodox-Zionist organization Misrachi (Misrachi synagogue on the first floor; Bnei Akiva youth center on the second floor). The museum on the ground floor is connected to the memorial. In the Memorial Room for the Victims of the Shoah, there are three computer terminals where visitors can learn about the lives and ultimate fates of the 65,000 murdered Austrian Jews. In the basement of the building, the architects Jabornegg & Pálffy installed a museum that not only offers archeological findings from the excavations on Judenplatz, but also boasts a multi-media presentation of Jewish life in the Middle Ages, a medieval city model, and documentation about the medieval synagogue. The museum rooms also grant direct access to the impressive excavations of the medieval synagogue. It was one of the largest synagogues in the Middle Ages, and you can still see the foundations of the hexagonal bima, the raised lectern for the reading of the Torah, as well as the foundation of the Torah shrine and parts of the walls and floor of the women’s shul.

Jewish Vienna Then ...and then I came to Vienna

It is difficult today, if not impossible, to say when the word, "Jew," first occasioned special thoughts in me. In my father's house, I cannot recall ever having heard the word, at least while he lived. I believe the old gentleman would have regarded special emphasis on this term as culturally backward. He had succeeded over the course of his life in becoming more or less cosmopolitan, an outlook that survived alongside a quite rough and ready nationalistic sentiment and which even colored my own.

In school, too, I found no cause which would have led me to change this received image. In high school I did learn to know a Jewish boy, whom we all treated cautiously, only because various experiences had taught us to doubt his reliability. But we didn't care all that much one way or the other [about Jews].

Not until I was fourteen or fifteen did I bump into the word, "Jew," more frequently, mostly in the context of political discussions. I felt slightly averse [to this practice] and could not fend off a feeling of unpleasantness which always came over me when religious squabbles were unloaded in front of me. But at that time I did not see the question as something special.

Linz possessed very few Jews. In the course of centuries their exteriors had become Europeanized and human-looking. Indeed, I even took them for Germans. The nonsense of this conception was not clear to me because I saw just a single distinctive characteristic, the alien religion. Since they had been persecuted because of it, as I believed, my aversion toward prejudicial remarks about them became almost detestation.

I did not yet so much as suspect the existence of a systematic opposition to Jews. Then I came to Vienna. Caught up by the fullness of impressions in the architectonic realm, downcast by the difficulty of my own lot, I did not at first grasp the inner stratification of the people in this gigantic city. I did not see Jews, despite the fact that Vienna already counted two hundred thousand of them among two million people at this time. My eyes and my senses could not keep pace with the flood of values and ideas of the first few weeks. Only when calm gradually returned and the agitated image began to clear did I look at my new world in a more fundamental way and also come upon the Jewish question.

I don't wish to assert that the way I got to know them was particularly pleasant. I still saw only the religion of the Jews and for reasons of human tolerance held aloof from attacks on this religion, as any other. Consequently, the tone struck by the antisemitic press of Vienna appeared to me as unworthy of the cultural heritage of a great nation. The memory of certain occurrences in the Middle Ages oppressed me; I would not wish to see them repeated. Since the papers in question were not generally well thought of (for reasons I had not yet fathomed), I mainly saw them as products of anger and envy, more than as the results of a systematic, albeit false, perspective.

I was strengthened in my opinion by what appeared to me as the immeasurably more worthy form in which the really big newspapers answered these attacks or, what occurred to me as still more praiseworthy, how they simply failed to mention them at all, that is, condemned them through silence.

I zealously read the so-called world-press (Neue Freie Presse, Wiener Tageblatt, etc.) and was amazed by the scope of what it offered its readers as well as the objectivity of its individual articles. I respected the aristocratic tone but was often somewhat uncomfortable with the overstated style. Yet this might have been in keeping with the verve of the whole metropolis.

Since I then regarded Vienna in this way, I thought of this explanation of mine as a valid excuse.... Adolf Hitler Mein Kampf

Today in Vienna Jewish families today live all over the city. The second district, Leopoldstadt, has a particularly high Jewish population, attracting mainly less wealthy Jewish settlers on account of the relatively low housing costs. This area has a high foreign population overall, with immigrants from all over the globe. There are also several Jewish institutions, for instance kindergartens of various Jewish groups, the Zwi Perez Chajes School, the Lauder Chabad Campus, the Jewish Vocational Education Center, prayer rooms, ritual baths and other religious educational institutions, and a Hakoah sports ground again in the Prater. You will also find Jewish shops, kosher supermarkets, butchers, bakers, restaurants, snack bars and, in the area around Tempelgasse, the Sephardic Center and Synagogue, as well as the new Jewish Center and ESRA psychosocial institution not far from the remnants of the Leopoldstadt Temple. Recent decades have also seen the emergence of a Jewish Institute for Adult Education (Volkshochschule) at Praterstern which also gives non-Jews the opportunity to learn more about Judaism in courses on Yiddish, kosher cookery, Israeli folk dancing, Klezmer music and religious issues.

Over the past 300 years, the Leopoldstadt district has been home to the most concentrated settlement of Jews in Vienna. It was also the location of the so-called Mazzes-Insel (“Matzoh Island”), where poor Jewish families lived, often in close quarters. The settlement dates back to the seventeenth century, when the so-called ghetto in the Unterer Werd could be found in today’s Carmelite Quarter; this neighborhood was destroyed at the end of the seventeenth century during the second major expulsion of Jews during the reign of Emperor Leopold, and a church was erected on the foundations of the synagogue. Since then, this city district has been known as Leopoldstadt. A small part of the Leopoldstadt Temple (Tempelgasse 5, 1020 Vienna) has been preserved. On the square where the large temple once stood there is now a modern building which houses ESRA and other organizations.

However, this expulsion did not prevent a new settlement by Jews in the city only a few decades later – this part of the city once again became the focus of Jewish settlers.

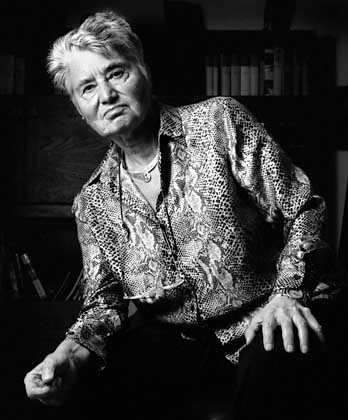

Inteview with Holocaust Survivor Ruth Klüger (Courtesy of Spiegel Online) "Vienna Reeks of Anti-Semitism" Ruth Klüger was born in 1931 to a Jewish family in Vienna. In 1992 she published the story of her ordeal in numerous Nazi concentration camps in her highly praised memoirs "To Continue To Live." |

SPIEGEL: Ms. Klüger, at the moment you have a research post at the University of California in Irvine, and before that you were a guest lecturer at the University of Göttingen. Do you sometimes go back to your home town Vienna?

Klüger: Yes. SPIEGEL: But the emotions you experience in Vienna must be very different to how you feel in Göttingen?

Klüger: Yes, what is strange is … how should I put it? Our personalities are such that we instinctively rely on our own experiences rather than using our brains. For me Göttingen is not a Nazi town, even though I know that Braunschweig is very nearby…

SPIEGEL: Braunschweig is of course where Hitler was made a German citizen in 1932.

Klüger: Exactly. But Vienna reeks of anti-Semitism. For me every cobblestone in Vienna is anti-Semitic. If I hadn’t fled with my mother and her friend in time, by the end of the war I could have ended up in Bergen-Belsen. But I have never been there, and I don’t go to these concentration camp memorial sites.

SPIEGEL: These memorial grounds are certainly not built with you in mind.

Klüger: It is just not my camp.

SPIEGEL: But you do you travel occasionally to Vienna?

Klüger: I did a guest professorship there. It was very unpleasant. The people I had to work with were awful.

SPIEGEL: So you believe that anti-Semitism is still deeply ingrained in the city? That it will always be there?

Klüger: Vienna will never be rid of anti-Semitism. I have the feeling the city doesn’t even want to be. When I got the invitation to go there, I couldn’t help thinking: “This is the university where your father studied.” And the first few weeks I was there, I couldn’t shake of the feeling that my father was standing behind me. I kept asking myself what he would have said if he had been there. And after a few weeks I knew what he would have said: “You are pretty stupid to have come here.”

Today, one cannot be Jewish in Vienna without remembering the Holocaust. Police vigilantly guard every Jewish event, memorial and institution; personal identification is required for entry. Although 10 synagogues exist, they do so against the shadowy backdrop of the 93 prewar synagogues that were destroyed by the Nazis. There are those who whisper that the Austrians “would do it all again if they could.” However, despite the indicators of Austrian apology and the revival of a Jewish community in the city, Vienna and its Jews retain an awkward tentativeness; born, perhaps, of unfamiliarity and disuse. ...even the Jews are unsure how to be Jewish. Time Line: History of the Jews in Vienna |

1194: Duke Leopold V installs Shlom as mint master. Shlom is the first Jew whose settlement in Vienna can be documented.

1204: First mention of a synagogue in Vienna (excavations on Judenplatz).

1238: Emperor Friedrich II takes the Jews of Vienna under his protection as “Chamber Vassals”.

1244: First Jewish Privilege of Duke Friedrich the “Pugnacious”.

1267: The church forbids social intercourse between Christians and Jews and ordains a dress code for Jews.

1420-21: The Jews, impoverished by a large fire in the “Jewish City” and subsequent plundering, have become dispensable. Albrecht V permits the expulsion of Jews from Vienna and Lower Austria. The more affluent among them are blackmailed and imprisoned, then burned at Erdberger Lände. Some prisoners commit suicide beforehand. The synagogue is destroyed (excavated remnants can be viewed today at Judenplatz).

From 1584: Individual “court-freed” Jews settle in Vienna. “Court Freedom” notably means the exemption from tolls, custom duties and community taxes.

1624-25: Jews are restricted to a ghetto in “Unterer Werd” consisting of 15 dwelling houses. In the decades that follow, the Jewish community grows to 132 houses.

1670: Emperor Leopold I decrees, mainly for religious reasons, a second expulsion of Jews from the city and country. The former Jewish area is renamed Leopoldstadt (Leopold’s City).

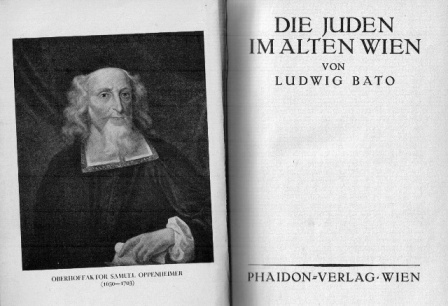

Circa 1680: Samuel Oppenheimer (and his household) and later Samson Wertheimer are granted the privilege of returning to Vienna as “Court Jews.” They are active mainly as military suppliers and mediators of international loans for the emperor. By 1700, there are ten privileged Jewish families living in Vienna.

1722: Diego D’Aguilar, a Marrano (forcibly baptized Spanish Jew), is called to Vienna to reorganize the tobacco monopoly. He helps finance the building of Schönbrunn Palace with 300,000 florins.

1718 – 1736: Due to peace treaties with the Ottoman Empire, Sephardic Jews who are subjects of the sultan are granted certain freedoms within the Habsburg Empire. They are permitted to form a legally recognized community in Vienna.

1763: Founding of the Vienna Chevra Kaddisha (Burial Fraternity).

1764: Restrictive laws governing Jews are established by Empress Maria Theresia, including severe restrictions on residence permits and privileges.

1781: A court decree by Joseph II forbids the charging of the Leibmaut poll tax which had been paid by Jews to enter certain cities since the Middle Ages.

1782: Joseph II passes the Toleranzpatent (Edict of Tolerance), which lifts numerous discriminating laws. However, the Jews gain no rights as a community.

1812: Convinced of the anti-Napoleonic loyalties of the Viennese Jews and their readiness to contribute financially, Franz I permits the opening of a temple and school at Dempfingerhof in Seitenstettengasse. Individual Jews are knighted. Salons, such as those of Fanny von Arnsteins and Cäcilie von Eskeles, become cultural centers.

1826: Consecration of the so-called City Temple, built by Joseph Kornhäusel.

1848: Jews are strongly represented among the activists of the Bourgeois Revolution.

1852: The Israelitische Cultus-Gemeinde (Jewish Community) is constituted with temporary status. Jewish immigration to Vienna from the provinces of the monarchy increases.

1858: Consecration of the Leopoldstadt Temple. The orthodox community moves from a small temple to the (later famous) Schiff Shul, the second most important synagogue in Vienna.

1867: Constitutional law: Complete equality of all citizens of Austria, including Jews. At the same time, anti-Semitism increases.

1890: Israelitengesetz (Jewish Law) to regulate the “external legal relationships of the Jewish religious community.”

1896: Theodor Herzl founds political Zionism with the publication of his brochure “The Jewish State.”

From 1897: Mayor Karl Lueger attracts petit bourgeois voters with economically motivated anti-Semitism.

1909: Founding of the “Hakoah” sports club.

1906 – 1911: Adolf Hitler lives in Vienna.

1914: Outbreak of the First World War. Jewish refugees from the Eastern war regions arrive in Vienna in large numbers.

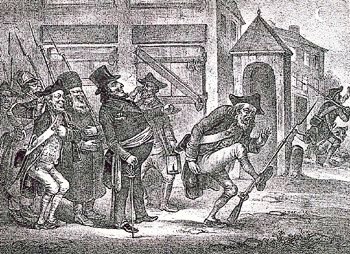

March 12, 1938: German troops march into Austria. The same night, the SA raids Jewish apartments and businesses.

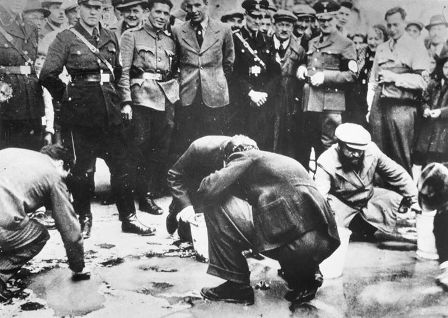

March through June 1938: Widespread anti-Jewish acts of violence. Jews are removed from public service. First deportations to Dachau concentration camp. Introduction of the Nuremberg racial laws. The Jewish Community is permitted to take up its official duties again, allowing official emigration.

Summer - Fall 1938: Numerous discriminatory decrees and edicts, such as the requirement that Jews take the first name “Sara” or “Israel” and the ban of Jews from public parks. Closing or “Aryanization” of many Jewish shops.

November 9 and 10, 1938: November Pogrom: Devastation and arson of all Viennese synagogues and temples. 6,547 Jews are arrested.

By May 1939: About 100,000 Jews have left the territory of former Austria.

October 1941: Start of mass deportations from Vienna. By the end of 1942, only 8,102 Jews remain in the city. By the end of the War, 65,459 Austrian Jews have been murdered in the concentration camps. Only 5,816 live to see the liberation of Austria.

April 1945: Re-establishment of the Vienna Jewish Community.

September 1945: Provisional re-opening of the City Temple, the only Jewish synagogue in Vienna that was not completely destroyed in 1938.

After the War: Much of Vienna becomes a camp for Displaced Persons from the East. Most are Jews who want to emigrate to Palestine.

From 1970: Vienna becomes a “bridge” for Soviet Jews, who cannot emigrate directly to Israel from the USSR. Many remain in Vienna.

1978: Talmud Torah School becomes a public school.

August 1981: Bomb attack by Palestinian terrorists at Seitenstettengasse 2.

1984: Re-opening of the Zwi Perez Chajes School, a high school founded before the Second World War by Chief Rabbi Chajes.

1988: Jewish Institute for Adult Education is founded.

1989: Establishment of the Jewish Museum of the City of Vienna.

1990-91: “Vienna Yeshiva,“ a vocational school for Jewish social work, becomes a public school.

November 18, 1993: Opening of the Jewish Museum of the City of Vienna at Dorotheergasse 11

1994: Official institutionalization of ESRA, a project aimed at psychosocial and sociocultural integration of traumatized Holocaust victims and their descendents.

1999: Opening of the Lauder Chabad Campus at Rabbiner Schneerson Platz close to Augarten.

October 25, 2000: Unveiling of the Shoah Memorial and opening of the Judenplatz Museum.

2001: Establishment of the Department for Restitution Matters within the Municipal Administration of the City of Vienna.

2004: Official opening of Theodor-Herzl-Platz on Vienna’s Gartenbaupromenade in the 1st district.

2005: The City of Vienna launches the Information Platform for Restitution in April. In May agreement is reached by the General Compensation Fund of the Republic of Austria and the Vienna Jewish Community (IKG) concerning outstanding restitution claims.

2008: Opening of the “S.C. HAKOAH Karl Haber Sport- und Freizeitzentrums” in the Prater

|

Sources:

Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (14th ed., Munich, 1932), pp. 54-70. Translated by Richard S. Levy.]

Karl Lueger and the Ambiguities of Viennese Antisemitism, by Robert S. Wistrich © 1983 Indiana University Press.

Hakoah Vienna: 100 Years Old and Still Powering On : Karen ProppJudisches Museum Wien http://www.jmw.at/

http://www.spiegel.de/international/0,1518,435879,00.html

Hitler in Vienna 1907-1913: Clues to the Future. By J. Sydney Jones. (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2002

WienTourismus (Vienna Tourist Board). Private Collections Copyright Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T 2010 |