Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Holocaust Prelude Early Nazi Leaders Nazi Propaganda Nazi Racial Laws Sinti & Roma Kristallnacht The SS SS Leadership Wannsee

Prelude Articles Image Galleries

| ||||||||

THE EVOLUTION, STRUCTURE, & MEMBERSHIP OF THE RSHA

Largely adapted from Michael Wildt’s article ‘The Spirit of the Reich Security Main Office’ first published in Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions Vol 6, Issue 3 (Dec 2005) pp 333-349)

The creation of a Political Police force was an early objective of National Socialism. Prussia was the largest state in Germany, including as it did the capital, Berlin, as well as other major cities. On 26 April 1933, Hermann Göring, initially acting as Prussian Minister of the Interior and then as Prussian Minister President, established the Secret State Police Office (Geheimes Staatspolizeiamt - Gestapa), which evolved into the Secret State Police (Geheime Staatspolizei - Gestapo). The Prussian police force had consisted of the uniformed or Order Police (Ordnungpolizei - Orpo) and the plain clothed Criminal Police (Kriminalpolizei – Kripo) which included the Political Police (Staatspolizei – Stapo). It was the political sections of the Kripo, together with the Stapo that were taken over and became the Gestapo, headed by Rudolf Diels.

At the same time as Göring was creating the Gestapo in Prussia, Heinrich Himmler was consolidating power as Police President of Bavaria, a position to which he had been appointed on 9 March 1933. Reinhard Heydrich occupied the position of chief of Department VI of the Bavarian Police, the political division. Heydrich was also head of the Security Service of the Reichsführer-SS (Sicherheitsdienst - SD), the intelligence branch of the SS, an office he had effectively created in 1931. The SD was intended to keep the opponents of the NSDAP under surveillance, to provide protection for the leadership and to fend off possible dangers from within the Party. As Himmler stated: "The SD will discover the enemies of the National Socialist concept and it will initiate countermeasures through the official police authorities." Throughout 1933-34, Himmler gradually gained control of all of the German States' police forces, except for that of Prussia, which remained under Göring's jurisdiction, until on 1 April 1934, Diels was removed as head of the Gestapo, signalling the accession of Himmler on 20 April as head of a unified national police force. Heydrich was appointed head of the Gestapo and immediately began a programme of drastic reorganisation. With effect from the summer of 1934, the SD was declared the sole intelligence service of the Party. Whilst the other branches of the police were employees of the State, members of the SD were employed by the Party, which paid their salaries. Most senior Gestapo men were recruited from among professional police officers; in contrast, the SD attracted an elite of ambitious intellectuals – lawyers, economists, professors of political science and the like. Although Heydrich now controlled both the SD and the Gestapo there was considerable overlapping in the areas of responsibility of the two organisations. This could sometimes lead to bewildering conflicts of interests. The SD had a monopoly of political intelligence, whilst only the Gestapo had the authority to carry out arrests or interrogations and send people to concentration camps. But the Gestapo still carried out its own intelligence work, which it could only do with information supplied by the SD. Both the Gestapo and the SD were responsible for "churches, sects, other religious and ideological associations, pacifism, Jews, right-wing movements, other anti-State groups, economics and the press". Clearly, some kind of rationalisation was required in the interest of greater efficiency. This was achieved when on 17 June 1936, the Party post of the Reichsführer-SS was amalgamated with the government office of Chief of the German Police, providing Himmler with the title of Reichsführer-SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei (RFSS u ChDtPol). Technically, Himmler was subordinate to Wilhelm Frick, the Minister of the Interior, but in practice he acknowledged only one superior – Adolf Hitler. The police were divided into two main branches: the `Main Office of the Security Police’, (Sicherheitspolizei – Sipo) headed by Heydrich, included the Gestapo and the Kripo. The `Main Office of General Police’ (Ordnungpolizei - Orpo) headed by Kurt Daluege was responsible for the Municipal Police (Schutzpolizei), the Rural Police (Gendarmerie) and Local Police (Gemeindepolizei).

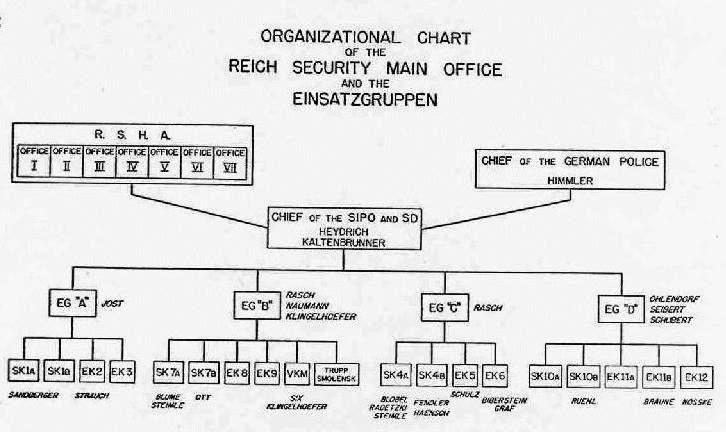

The final major reorganisation of the police occurred on 27 September 1939, when Himmler issued a decree creating the Reich Security Main Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt – RSHA), fusing the Sipo and SD, with Heydrich as head of the new organisation. Thus was created a monstrous bureaucracy that was to oppress and terrorise Europe. Heinrich Müller was placed in charge of the Gestapo, with Arthur Nebe as head of the Kripo. The headquarters of the RSHA were situated at the former Gestapo building at the Prinz-Albrecht-Straße 8 in Berlin, with other offices spread across the city and other branches located throughout Germany. Much to the displeasure of Heydrich, who wanted to control of all of the police forces, the Orpo remained outside of the ambit of the RSHA. The completed police state was now in place and ready to begin its campaign of wholesale atrocity and murder. Six Einsatzgruppen, numbering some 1,800-2,250 SD, Sipo and SS members, followed closely in the wake of the Wehrmacht as it invaded Poland. Selected by the RSHA, they were responsible for killing some 15,000 Jews and members of the Polish intelligentsia during the months following the invasion. With the commencement of `Unternehmen Barbarossa’ in June 1941, this figure was to be dwarfed by the activities of the four Einsatzgruppen and their assistants in eastern Poland and the Soviet Union. Testifying on 3 January 1946 at the Nuremberg trial of the principal war criminals, Otto Ohlendorf – at the time still in his late thirties – shocked his listeners with the frank admission that he, as the leader of Einsatzgruppe D, had been responsible for the murder of 90,000 people in the Soviet Union during 1941–42. Even 50 years on, US prosecutor Telford Taylor remembered Ohlendorf as a handsome young man, who had spoken softly and with great precision and apparent intelligence. Taylor recalled the paralysing silence in the courtroom which had followed Ohlendorf’s detached and emotionless testimony only too clearly. It was also 50 years later that Daniel Jonah Goldhagen raised a key question. Most reflections on Nazi perpetrators or explanations of their deeds had sought – and continue to seek – possible motives that might have induced ‘ordinary’ Germans to commit genocide. There must have been factors that had eroded moral barriers or cultural boundaries in such a way as to have rendered ordinary people capable of perpetrating monstrous crimes. What Goldhagen asked was: were the perpetrators indeed forced to commit these crimes, or were they willing, even eager, to persecute and exterminate the Jews? Did these men murder because they had to, or because they were allowed to do so? This question cannot simply be answered by supporting one side or the other. Obviously, there is no simple or unambiguous answer. The significance, however, lies in the asking. There are, in fact, numerous images of Nazi perpetrators. First, there is the image of the SS men as sketched by Eugen Kogon, a former inmate of the Buchenwald camp, in the immediate post-war period. He portrayed them as brutal, poorly educated, primitive and socially deprived individuals, unable to hold down normal jobs in civil society. Even when the Nuremberg Trials revealed that the German élite – lawyers, physicians, officers, and entrepreneurs – were deeply involved in the mass murder and genocide, a majority of post-1945 Germans were still eager to believe that these men were exceptions, a misled criminal minority. Furthermore, in the atmosphere of the beginning of the Cold War, it was not long before former war criminals were viewed as unjustly sentenced warriors against communism, who should now be released from prison. The second image of the perpetrators of Nazi crimes is the picture of Adolf Eichmann in his glass booth in the Jerusalem District Court. Hannah Arendt and her dictum about the `banality of evil’ shaped the image of Nazi perpetrators in the decades that followed. This was due not only to the impact of her reasoning and her brilliant prose style, but was also the result of a concurrent shift within the social sciences. This is confirmed by the fact that Raul Hilberg, who published his famous book on the Holocaust in the same period, also portrayed the perpetrators as part of the normal, smoothly functioning modern bureaucracy that was responsible for genocide. Hilberg was interested not so much in individuals as in administration, bureaucracies, procedures, and structures.

For many years, the bureaucrat, the technocrat, the armchair culprit was (and continues to be) the dominant image of the perpetrators of Nazi crimes. In popular conception, these perpetrators focused on their own duties, accepted the administrative tasks assigned them, and carried them out correctly and conscientiously without feeling responsible for the overall consequences. In short, they perceived themselves as small cogs in a huge machine that was beyond their control. This image not only corresponded to the defence formulated by numerous perpetrators, but also matched the daily experience of many individuals in a modern, bureaucratic society with a clear-cut division of labour. Genocide was seen as an industrialised, production-line form of killing. The bureaucrat became a technician of death, who maintained and optimised his part in the huge machinery of annihilation without wasting a thought on the murderous meaning of the entirety, much less bothering himself about moral scruples. If historians considered questions of ideology or intent at all, they focused only on Hitler, Goebbels, Himmler, and the like – that is, on the very top level of Nazi leadership. Thus, the longstanding debate between ‘intentionalists’ and ‘functionalists’ has been an unequal one. The largely invalidated ‘intentionalist’ concept of the Third Reich was of a traditional dictatorship, in which one furious anti-Semite at the top could induce an entire society to commit genocide. The `functionalist’ breakthrough occurred in the 1980s and 1990s; research, based on documents from East European archives opened after 1989, has yielded new information about the large number of middle-ranking SS officers, the officials in the occupation administrations, the army officers responsible for mass murder, the disastrous conditions in the ghettos, and the deportation of Jewish victims to the extermination camps. This more recent research on Nazi perpetrators has brought to light individuals who were able to decide what to do, who were able to choose to act in one way or another. Studies by Götz Aly, Susanne Heim, and others have shown that many of these individuals were university-educated – not part of a marginal or excluded minority, but members of the mainstream elite from the very heart of German society. For all the new insights, however, Goldhagen’s question remains unanswered. Were these university graduates forced to plan, to design and even to execute genocide, or were they allowed to do so? In recent years, the image of Nazi perpetrators has been broadened to include the many radicals and the high degree of radicalism among them, but still very little is known about the process of radicalisation. As students, none of the young men who were later to play a leading role in the RSHA had envisioned the systematic annihilation of the European Jews. Even thereafter, when they joined the SD and the Gestapo, there were no indications of plans for genocide being generated among them. Nonetheless, they were the ones who ultimately not only took part in the planning of genocide, but also executed the actual plans as leaders of the Einsatzkommandos and Einsatzgruppen. A total of about 3,000 people, including secretaries and lower officials, were employed in the RSHA in Berlin. About 400 men (and one woman) had positions at the highest level, as Referenten (departmental officials), Gruppenleiter, or Amtschefs (heads of office). Research into a sample of 221 individuals who constituted the leadership corps that worked in the RSHA more or less continuously has produced some interesting results. 77% were born after 1900; most were from lower-middle-class families and were the first in their families to attend university, with two thirds of this group actually completing their university degrees, and one third (or 50% of those who studied at university in the first place) gaining a doctoral degree. The generation of those who were children or youngsters during the First World War and, from their perspective, were therefore denied the opportunity of ‘proving themselves’ on the front lines, formed the reservoir from which the RSHA recruited its leadership corps, and included among their number Heinrich Himmler himself. For this young generation, the lack of opportunity to prove themselves as brave warriors represented an enduring blow to their self-confidence. It infused them with a feeling that they would have to prove themselves in the future. And the fact that these young men became such merciless, cruel officers during the Second World War may be related to the circumstance that they had never seen a battlefield before, that they had not been soldiers like their fathers or older brothers, that they lacked the image of martial masculinity. This was a generation of young gamblers – and of non-believers in bourgeois society. What these youngsters experienced first-hand was not so much the so-called home front during the First World War as post-war shortages, political upheaval, revolution, violence and hatred. They lived through the post-war economic disaster leading to the hyperinflation of 1923, which turned bourgeois society upside down. This last point was of major importance, as bourgeois values such as hard work, diligence and thrift – and attendant adages asserting that one would enjoy a peaceful old age if one only worked hard and saved one’s money – became worthless. Living in such times meant that one came to despise bourgeois values: the promises of bourgeois society seemed to be a deception. Discontinuity, a break with the past and a focus on the future became the hallmarks of this generation. That future, however, was not so much envisioned in terms of favourable material conditions or of the rational and dispassionate appraisal of resources, as imagined to depend on one’s will and mental strength. For the young men who would later take up leadership positions in the RSHA, the years spent at university would prove to be among the most decisive in their lives. Only about one quarter of the RSHA leadership came from families with a university background; 60% were from the lower middle class, with fathers who were small businessmen, technicians, engineers, craftsmen and, above all, civil servants in intermediate or higher positions. The Reich Security Main Office was an institution for social climbers. Significantly, more than three quarters of those in the top ranks of the RSHA had passed their Abitur (the school-leaving examinations), and, as mentioned above, two thirds had attended the university while nearly one third also held doctorates. Thus, the leadership corps of the RSHA was by no means a collection of human failures: it was not recruited from the margins of society, but was part of the academically educated bourgeois élite. More than half of those who held a university degree had studied law or political science, but a significant proportion, about 22%, had majored in the humanities – in subjects such as German literature, history, theology, journalism and philology. The highest positions within the RSHA were taken up by lawyers, historians, philologists, and journalists. Those who held degrees in fields other than law were, for the most part, to be found in positions in the SD. Numerous members of the RSHA leadership had been activists in the National Socialist Student Association (Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund, NSDStB). All those who, in their later SS biographies, mentioned membership of the NSDStB before 1933, also listed the political offices they had held in the organisation. Mere membership was not enough: what really counted was one’s activism. These student activists saw themselves as the revolutionary core of a movement aiming to fundamentally revamp the university according to völkisch principles. They called for the dismissal of all politically liberal or leftist, and especially of all Jewish professors. These men already perceived themselves as members of a future leadership élite. Their goal was to become leaders, not citizens – not the elected, but the chosen, natural élite of the people. These young law and political science students designed a model of law and of the state that had little in common with the Weimar constitution. Their concept of leadership was not based on laws or legal principles, but rather on history and actions. Leadership, action, ideas – these were the dominant elements in the political thinking of these young men. Leadership, they maintained, was confirmed by deeds. A leader proved himself through the superiority of his deeds and their success. Success alone counted and legitimated both actions and ideas. Deeds legitimated themselves. The world view (Weltanschauung) of this generation was characterised by a specific structure of political thought rather than by specific political content. Politics was always understood as a dramatic, absolute, unlimited expression of the will, which was not to be subordinated to regulatory norms or moral laws. What is significant in the academic debates of this generation about state, Volk and Weltanschauung is the connection between theory and practice, between ideology and politics. None of these young academically educated men who imagined that they were the future élite of a New German Reich regarded themselves as intellectuals, as disinterested scholars. Scholarship had to be political; Weltanschauung had to prove itself in practice; ideas could prove their worth only through deeds. Those who were to become the leaders of the RSHA did not want to be bookworms or scholars, but aimed instead to become a kind of spiritual leadership which would not only outline new plans and concepts, but realise them. Cultural anti-Semitism was, of course, also a characteristic shared by these young students; in this respect, they did not differ from the bulk of the rest of the German educated middle class of the period. This was an ideology that always sought to realise the total goal, the whole utopian enterprise: it was incapable of compromise and proved itself through acting, not through arguing. Success or failure alone

determined whether one was right or wrong. This unlimited, radical ideology, this unbound connection between ideology and politics had already proved to be a threat to all liberal, democratic and, of course, Jewish professors and students at Germany’s universities before the Nazi rise to power. It became a greater menace to them thereafter. However, once this specific ideology had fused with an institution intentionally designed to have no limits, these two radical elements would initiate a process of dynamic radicalisation. If the professional life of the later RSHA leaders is examined, the biographical option of a career in politics is repeatedly encountered. Even to those who, like Hans Ehlich or Erwin Weinmann, for example, were respected physicians, with substantial incomes, families, homes and so on, there came a time in their lives when they decided to realise their political vision, to leave their jobs and join the SS. Politics, in the sense of policy making, of creating a new political order in Europe, had always been a serious option in their lives. But National Socialism’s political victory offered them an opportunity to join one of the Nazi regime’s most powerful institutions: the political police. What was special about this historical situation had little to do with the observation that, in times of political upheaval, young political activists can be expected eagerly to await an opportunity to intervene in events, rather than watch from the sidelines. What was unique in this case was the character of the institutions they joined. As a result of Himmler’s and Heydrich’s success in the intra-Nazi struggle for control of the police in 1936, both the police and the formerly relatively insignificant SD developed into institutions charged with much more than their original functions, namely terrorising the opponents of the Nazi regime. In keeping with the SS’s racist perspective, the police and the SD were destined to take on a much larger task: “to protect”, as Himmler put it in 1937, “the German people as a total organic being, its life force, and its institutions, from destruction and decay”. And Himmler added that the authority of a police charged with such duties “cannot be interpreted in a restrictive manner”. It was not the state that was at the centre of National Socialist political thought, but the Volksgemeinschaft, (the German ethnic community) and the `Aryan’ race. Hitler himself had repeatedly pointed out in Mein Kampf that the state was only a tool for race and Volk. The new political order the National Socialists intended to establish was the racist Volksgemeinschaft: a revolutionary, utopian and destructive order, not an old-fashioned dictatorship. In the “struggle to the death” against those labelled as the Nazis’ ideological opponents – that is, above all against the Jews as the embodiment of the “anti-race” or “anti-Volk” – the police had to be completely free to resort to any conceivable means to win the war of worldviews. “Were we to fail to fulfil our historical duty”, Heydrich asserted in an article published in Das Schwarze Korps in the autumn of 1935, “through being too objective and too humane, then no one will make allowances for mitigating circumstances. They will merely say: they did not fulfil their duty to history”. There is an important distinction here. Even where a repressive, authoritarian understanding of the state holds sway, one finds rules, regulations and a legal order – albeit not a democratic order, but one which state institutions respect. These rules may be repressive, but even people subjected to individual suppression or persecution in such a dictatorship can rely on them. The existence of a state order implies a legal order. When the political order is based on race and Volk, no one can define the limits or fix a system of rules and regulations, because race and Volk are fluid terms defined politically, rather than by a legal order. The creation of the racist Volksgemeinschaft as a political order in Germany meant not only that the bourgeois state was destroyed but, in particular, that boundaries could be ignored and that political action was no longer limited. Policy making was transformed into ‘policing’. The Reich Security Main Office, a mixture of state institutions and Nazi Party organisations, was not a police authority in the sense of the Prussian administration. It was a new type of uniquely National Socialist institution, linked directly to the Nazi concept of Volksgemeinschaft and to the organisation of the Nazi state. The RSHA was a creation of the police authority in the sense that it was a supervisory body, an organisation that defined its task as the implementation of overall racist control. Here, the police was not an instrument for preventing crimes or persecuting criminals, but aimed to establish a total racist order and to exterminate the regime’s enemies. This concept of a police authority, which was political in an all-encompassing sense, corresponded to the ideological will to create a new political order, set apart from all that was old and conventional. Consequently, active involvement in the RSHA was also perfectly possible for those who did not view themselves explicitly as National Socialists, since it offered a link between the will to participate in designing a new political order and a structure through which this order might be created. Those who saw themselves as the élite of a New German Reich believed that they had found the tool, the institution through which to realise their utopia. Allowing Weltanschauung to move beyond previous boundaries, rather than drawing up such limits, was the trademark of a new and radical institution like the Reich Security Main Office. The RSHA was a flexible organisation. This was precisely the kind of political ‘fighting administration’ (‘kämpfende Verwaltung’) Heydrich had called for. It was capable of expanding or shrinking, building new departments and dissolving old ones, shifting priorities or establishing new ones, and initiating intra-agency task forces. For all the slow-moving administrative procedures that were also typical of an entity like the RSHA, it could enter into new dynamic phases in order to realise its political goals. Both the political police and the SD were subject to numerous changes and reorganisations: they were institutions that underwent constant change at the hands both of their own respective policy makers and of the leaders of the Nazi regime, depending on the political framework and definition of their tasks. For example, new ‘groups’ responsible for the occupied areas were created. Even Heinrich Müller, the head of the Gestapo, did not have such a group in mind when he planned the various divisions and departments in the autumn of 1939. Eichmann’s Office IV B 4 – the equivalent of a department in size and importance – became a central office for deportation in all of Europe. Such new core sections, both in Eichmann’s apparatus and in the important group IV D, no longer employed the kind of criminal police commissar who had been trained as a policeman in the Weimar Republic and had then become a Gestapo officer because of his anti-Bolshevist verve. Now there were significantly younger men, some of them administrative lawyers, some SD people, most of whom had been ‘on active duty’ before or after they took up administrative positions in the RSHA.

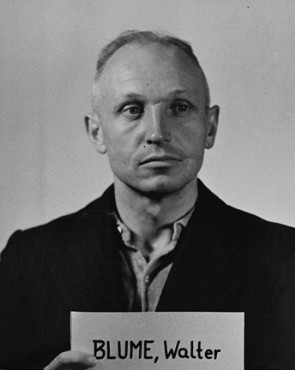

The RSHA was also a mobile organisation. It did not limit itself to operating from Berlin, with a staff of officials sitting behind their desks doing paperwork and writing orders that someone else had to carry out. One illuminating example is the case of Dr Walter Blume. Born in 1906 in Dortmund, he was the son of a teacher. Walter Blume grew up in a Protestant family, studied law and, as a student, was a member of right-wing groups. In 1933 – Blume was 27 years old at the time – he became head of the political police in Dortmund. One year later, he was ordered to Berlin as a member of the central Gestapo board; a few months later he became the head of the Gestapo in Halle and then held the same position in Hannover. In 1939, he became head of the Gestapo in Berlin. From there he moved to the RSHA, where he was responsible for all personnel matters of the Gestapo and the Criminal Police. In 1941 Blume became the leader of Einsatzkommando 7a, which killed thousands of Jewish people in the Soviet Union. He returned to the RSHA in the autumn of 1941, was sent to Slovenia a year later and given charge of combating partisan groups. Next he was ordered to Düsseldorf in the capacity of chief of the regional police. In 1943 Blume was appointed chief of the police forces in occupied Greece. He returned to the RSHA in late 1944. Blume is an example of a man suited to all assignments, who functioned equally well behind a desk in Berlin, at execution sites of in the Soviet Union, and as the chief of the German police forces in occupied Greece. The RSHA was run by men just like him: flexible, mobile, eager, able to perform their duties everywhere. They were not bureaucrats or technocrats. They understood that their task was ideological, that they were part of a project that had to be realised not in Berlin alone, but wherever they happened to be assigned. They linked their work in the central office in Berlin to practical operations elsewhere; they participated in the actual practice of terror, rather than creating the horrors of the occupation regime simply through regulations and decrees. The RSHA as an institution was itself as mobile and flexible as the men who ran it. Its central office was in Berlin, but it realised its full power and potential at local level. Ideally, the plan of those who constructed the RSHA was to unite under one institution political initiative, problem analysis and operational organisation, together with implementation. No administrative or legal norms were to limit that institution: it was to be allowed to act everywhere and with all available means “for the coordination of all the political business of the SS”, as Himmler’s written order of 25 June 1942 stipulated. War created the necessary context for the further development of the RSHA. War made it easier to kill, and made murder an everyday practice. The entire legal framework of a bourgeois society – insurance, property rights, financial agreements, and all the other rules and regulations with the potential to hinder RSHA operations – vanished in the occupied areas. There were no troublesome clerks and bureaucrats insisting on laws and agreements, no civil rights or criminal code. The RSHA could act as it saw fit without restraints or political reservations. The war against Poland was undoubtedly a watershed. The operations of the Einsatzgruppen, most of whose leaders became part of the RSHA leadership a short time later, were far more horrible than the acts of terror that had been committed by the same men in their earlier positions as Gestapo or SD leaders. In autumn 1939 the Einsatzkommandos carried out executions that were similar in method to the mass executions later practiced in the occupied Soviet territories. During the operations in Poland, numerous SS leaders who were later, within the RSHA, to be responsible for the `Final Solution’ learned to think on a ‘large scale’ and to cross all the limits of civilisation. In a sense, the practice of genocide in Poland in the autumn of 1939 marked the actual establishment of the Reich Security Main Office. After occupying Poland, the Nazi regime planned to annex western Poland and to ‘Germanise’ it. ‘Völkische Flurbereinigung’ (or ‘ethnic cleansing’) was the term Hitler coined for this task. What institution could be better suited to the assignment than the RSHA? In late October 1939 Himmler ordered that one million people – Jews and Poles – be forcibly removed from western Poland to the so-called Generalgouvernement (the Nazis’ term for occupied central Poland). Besides dedicated personnel, this large-scale expulsion required trains, deportation areas, barracks and food for the deportees (even if the actual intention was to allow them to starve). There was a shortage of trains because the German army needed them for the French campaign. And the German occupation administration in the Generalgouvernement refused to allow the tens of thousands of deportees to enter because there was a shortage of accommodation, food and other necessities. As a result, the number of people scheduled for deportation was first reduced and the deportations postponed. In the end, the entire plan was abandoned. The ideological vision of the world as an arena of the will – in which reality was an object to be shaped in whatever way one desired – had been put to a difficult test by the many obstacles which the RSHA faced. Yet all these very real obstacles did not cause the leaders of the RSHA to lose any

degree of confidence in their ability to achieve the goal of Germanising the annexed regions and making the Reich ‘Jew-free’ (‘judenrein’). As the Wehrmacht’s victory over France in 1940 became obvious, an old anti-Semitic plan to expel the European Jews to Madagascar was revived. It could only be realised if Germany gained control of the seas. Without a victory over Britain, the plan would remain a chimera. Nevertheless, the German Foreign Office and the RSHA created detailed plans for deporting the Jews to Madagascar. Within the Nazi leadership, the ‘Madagascar plan’ was earnestly discussed – until it became apparent that Hitler preferred attacking the Soviet Union to attacking Britain. Notwithstanding the scholarly debate about the seriousness of the ‘Madagascar plan’, the fact of the matter is that this alternative was pursued eagerly within the RSHA, and the number of Jews slated to be deported to Madagascar reached more than three million. After its failure only a few months earlier in western Poland, where the RSHA had been unable to expel the targeted number of one million Jews and Poles, it nevertheless proceeded to plan a deportation operation three times larger than the first. Moreover, within a period of only a few months, the RSHA had broadened the scope of its plans to include not only the Jews from Germany and western Poland, but those from all over western Europe. Another aspect of this plan is also significant. The RSHA operatives were, of course, aware of the fact that the island of Madagascar had neither enough space, nor the agricultural land, food and water resources to sustain an additional three million people. It was clear that at the very least, tens of thousands of people would die of starvation or as a result of epidemics. Although the ‘Madagascar plan’ as outlined in the summer of 1940 was not explicitly a plan for genocide and mass murder, it still clearly bore the stamp of genocide. The failure of this plan, therefore, did not mean the end of the intentions it harboured. Hitler complained that the ‘solution to the Jewish question’ was hampered only by territorial problems: there was no place to which he could deport the Jews. Therefore, the war against the Soviet Union raised the hopes and expectations of the racial planners within the RSHA. All their problems now seemed to disappear. The Jews could be expelled to the East. Once again, these new expectations made the plans more monstrous. In December 1940 Himmler spoke of nearly six million Jews who were to be deported – a number derived from plans prepared by Eichmann’s department within the RSHA. This total included west European Jews and the Jews from south-eastern Europe as well, even though this region had not yet been occupied by the Nazis. In the space of a single year, the number of potential deportees had increased from one to six million, and the area from which they were to be driven out had been extended from western Poland to all of Europe. Despite all obstacles – and, in late 1940, none of these barbaric plans had been realised – the RSHA did not give up the project of making Germany and occupied Europe ‘judenrein’ and establishing a new racist order across the continent. Although all these plans had failed, the RSHA had been unwilling to rethink the plan itself, or even to revise it. The project had to be realised at all costs and despite all obstacles; if the difficulties increased, then the ‘solution’ simply had to be designed more radically than before. These men could not turn back, but could only become more radical. Therefore, if there were no place to which the Jews could be deported, then other means of reducing the number of those people had to be considered. The war against the Soviet Union opened up an apparent and, again, radicalised solution to this dilemma. After the expected rapid victory, the European Jews were to be deported to the East. At the same time, the Einsatzgruppen of the RSHA were to be charged with the radical task in this war of Weltanschauung of liquidating ‘Judeo-Bolshevism’ by murdering the Soviet party and state functionaries and the Soviet intelligentsia. In March 1941 Hitler conveyed his orders regarding ‘Special Tasks Commissioned by the Führer’ (‘Sonderaufgaben im Auftrag des Führers’) to Himmler. These were to form the political basis for the Einsatzgruppen to act with far-reaching executive powers, and with the greatest possible degree of freedom with respect to the Wehrmacht. The SS and police leaders were to decide completely independently who was to be considered part of the ‘Judeo-Bolshevist’ intelligentsia and not part of the military. Heydrich expressly left it up to the local Einsatzkommando leaders to decide who was to be executed. The description of the groups of people who were to be murdered was only a kind of general guideline. The academic debate about the differences in the practice of the various Einsatzgruppen fails to recognise the practical character of an order that was first and foremost an authorisation. Only in the rarest of cases, when the persons giving and receiving an order were in the same place at the same time, were orders unequivocally defined instructions for action. In most other situations, orders had to be modified and adapted to fit the specific situation. The leaders of the Einsatzkommandos had been specifically selected by the RSHA because they were expected to be able to reach an appropriate decision that matched the intentions of Heydrich’s order, even under conditions that might be difficult to determine completely and precisely beforehand. The RSHA under Heydrich had gained the political upper hand with respect to the ‘solution of the problem of the European Jews’ in 1941, and it proved to be a constantly forward thrusting, radical element in the Nazi regime’s decisions regarding deportation. With the September 1941 decision to deport the German and Austrian Jews to the occupied Polish and Soviet areas while the war was still going on, the last barrier to all-out genocide fell. Self-made constraints, such as disease and epidemics in the overcrowded ghettos, where people were forced to live in disastrously unhygienic conditions and with insufficient food, or the definition of ‘Jews who were unable to work’ as ‘Ballastexistenzen’ (‘creatures whose very existence is a burden’, worthless people – a term beloved of the euthanasia enthusiasts and the eugenicists who preceded them) offered the perpetrators the legitimacy for realising genocide as a ‘solution to a problem’. Again, the failure of the National Socialist deportation plans did not motivate a change in the established goals, but, instead, the desire to realise those goals at all costs through ever-more radical means.

At the beginning of the Nazi regime, the protagonists who were later to join the RSHA did not think in terms of genocide. But genocide as a possibility was inherent in their thinking. The war in the East provided the geographical space in which the process of radicalisation could lead to genocide. Whereas there were numerous legal and administrative obstacles for the RSHA to overcome within the territory of the Reich, such limits, characteristic of a legalistic bourgeois society, did not exist in the East. The dismantling of limits there also meant the dismantling of bureaucracy, as well as the deregulation and the personalisation of decision-making processes. In Estonia, Lithuania, the Ukraine, and the Crimea, neither the German legal code nor the handbook for German administrative officials was valid. The young university educated men serving as Einsatzkommando leaders were on their own there. They were local rulers, far removed from the central office in Berlin, who made life-and-death decisions. These men had never been little wheels in a huge machine of destruction, never mere functionaries who only looked at their narrow task, never bureaucrats obeying only the orders that came from above; these men had designed the concepts, and constructed and operated the apparatus that led to mass murder and genocide. These RSHA men did not see themselves as ivory-tower scholars or mere thinkers. On the contrary, the success of a theory had to be demonstrated in practice. Racism and anti-Semitism could be found all over Europe, but in Germany they entered into a unique union with a Weltanschauung fomented by the human utopias and historical myths of the nineteenth century. Always dramatic, ruthless, unbounded and oriented toward the whole, this Weltanschauung feared nothing. This project – not only of recreating Germany with a new ‘race’ but of creating a new racial order for all of Europe; not merely of designing a braver new world, but turning it into a horrific reality – led droves of intellectuals, academics and scientists to become ready supporters of the Nazi regime. At last, philosophers could believe that they were in power; physicians could see themselves in the role of uncontrolled designers of human life; historians could think themselves in a position to shape world history. The participation of these RSHA members of the intellectual élite in the National Socialist crimes and their role as perpetrators was not exclusively functional, rational and technical, as they tried to convince the world after the war. Failure to acknowledge the passion behind the mask of rationality, will in turn result in a failure to recognise the energy and enthusiasm of these perpetrators.

Sources:

Aly, Götz and Heim, Susanne, Architects of Annihilation: Auschwitz and the Logic of Destruction, Phoenix, London, 2003. Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1997. Browning, Christopher R. Fateful Months: Essays on the Emergence of the Final Solution, Holes & Meier, New York, 1991. Browning, Christopher R. The Path to Genocide: Essays on Launching the Final Solution, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997. Butler, Rupert. An Illustrated History of the Gestapo, BCA, London, 1992. Goldhagen Daniel Jonah. Hitler's Willing Executioners, Little, Brown and Company, London, 1996. Hilberg, Raul. The Destruction of the European Jews, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2003. Höhne, Heinz. The Order Of The Death's Head, Pan Books Limited, London, 1972. Kogon, Eugen. The Theory and Practice of Hell: The German Concentration Camps and the System Behind Them, Berkley Books, New York, 1998. Padfield, Peter. Himmler – Reichsführer-SS, Macmillan Publishers Limited, London, 1991.

Copyright H.E.A.R.T 2007

|