Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Holocaust Prelude Early Nazi Leaders Nazi Propaganda Nazi Racial Laws Sinti & Roma Kristallnacht The SS SS Leadership Wannsee

Prelude Articles Image Galleries

| |||||

Leni Riefenstahl

Helene Bertha Amalie “Leni” Riefenstahl was born in Berlin on the 22 August 1902 and began her career as a ballet dancer, employed by Max Reinhardt among others, for dance performances in the early 1920’s.

Her father Alfred Riefenstahl was said to have wanted his first child to be a son so that he could carry on the firm that had provided a secure amount of wealth to the Riefenstahl family. However, as the young girl Leni grew into young adulthood, she felt her passions grow in the artistic direction that had been a staple of her mother’s life.

At the age of 4, Leni began to write poetry and paint. Along with this, Leni felt that from a very early age she was an athletic child, due to the behest of her father. At age twelve, she recalled joining a local gymnastics and swim club called "Nixe". It was her mother that noticed that Leni had quite the artistic bent. She perceived that Leni had the ability to paint with a natural understanding of composition and balance, which were two of the profound qualities in the later films of Leni Riefenstahl.

In 1925 she made her film debut as an actress in Der Heilige Berg the first of a series of well photographed movies about the Alps, made by Arnold Franck, the father of the mountain cult in the Wiemar cinema.

Riefenstahl became a leading figure of this cult, starring in Franck’s Der Grosse Sprung (1927), Die Weisse Holle vom Piz Palu (1929), Sturm uber dem Mont Blanc (1930) and Das Blau Licht in 1932, which she co-authored and directed for the first time, produced and played the leading role in, winning a gold medal at the Venice Biennale.

Riefenstahl first remembered hearing of the political name of Adolf Hitler around the filming of Das Blaue Licht. However, at this time, Hitler was a large political force in German politics. Riefenstahl attests to a naivety about the political world due to her rigorous and involving filmmaking during Hitler’s political rise that his name had sadly no recognition for her. Yet, Hitler had noticed Leni and her work in Das Blaue Licht along with the earlier Arnold Fanck films and would later call on her and her talents for the Party.

In late February of 1932, she attended one of his election speeches at the excited and overcrowded Berlin Sports Palace. Once again, like at the films, she was struck by the power of this moment that she had to make up her own mind and meet the speaker. She quickly wrote a letter to the Nazi paper "Völkischer Beobachter", in which she requested a meeting with Hitler before she had to leave Germany for a Arnold Fanck shoot in Greenland.

In 1933 she made her last film for Franck titled SOS Eisberg, before being appointed by Hitler as the top film executive of the Nazi Party. Hitler saw Leni Rifenstahl as a director who could use aesthetics to produce an image of a strong Germany imbued with Wagnerian motifs of power and beauty.

In 1933 he invited Reifenstahl to direct a short film, Der Sieg des Glaubens (The Victory of Faith), which was filmed at that year’s Nuremburg Party Rally. This film was the template for her most famous work, Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will), shot at the Nuremburg Party Rally of 1934.

Reifenstahl initially refused Hitler’s commission for the film, but relented when she received unlimited resources and full artistic control for the film. Triumph of the Will, with its evocative images and innovative film technique, ranked as an epic work of documentary film making, and is widely regarded as one of the most masterful propaganda films ever produced.

It won several awards, but forever linked the artist Leni Reifenstahl with National Socialism.

Equally stunning were Reifenstahl’s directorial efforts in Olympia, which captured with haunting effectiveness the images of the 1936 Summer Olympic Games in Berlin. It was for Olympia that Reifenstahl pioneered numerous cinematographic techniques, such as filming footage with cameras mounted on rails. Olympia’s forceful blend of aesthetics, sports, and propaganda again won Rifenstahl accolades and awards, including Best Foreign Film honours at the Venice Film Festival and a special award from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) for depicting the joy of sport.

By her own account, the advent of the Second World War and the rapid escalation of violence under the Nazi regime had an unfavourable effect on both Reifenstahl and her career. Early in the German invasion of Poland, she witnessed an incident that seemed to shake her confidence in the movement she had glorified in her films.

During the Invasion of Poland, Riefenstahl was photographed wearing a military uniform and a pistol on her belt in the company of German soldiers. she had gone to the site of the battle as a war correspondent. On 12 September 1939 she was in the town of Końskie when 30 civilians were executed there, in retaliation for an alleged attack on German soldiers.

While accompanying German troops near Konskie, the filmmaker witnessed the execution of Polish Jews and this upset her so much, she halted filming and went to Berlin, to seek an audience with Adolf Hitler.

Her distress was short-lived, she was back in the General Gouvernment and filmed the victory parade along the Ujazdowsskie Avenue on the 5 October 1939. The podium where Hitler took the salute was located in front of the Ujazdowski Park near Chopin Strasse.

In 1940 Riefenstahl commenced filming on Tiefland (Lowlands), a story set in the Spanish Pyrenees, this was a project she had earlier shelved when persuaded by Hitler to film Triumph of the Will.

In 1944 she married Wehrmacht Major Peter Jacob, but this marriage ended in divorce, and during the 1960’s she developed a life-long relationship with Horst Kettner, who was forty years her junior.

In the post-war years she was the subject of four denazification proceedings which finally declared her a Nazi sympathiser. Although never a member of the Nazi Party, Reifenstahl found it difficult to overcome her association with the propaganda films she had made during the early Nazi period. Riefenstahl later said that her biggest regret was meeting Hitler: "It was the biggest catastrophe of my life. Until the day I die people will keep saying, 'Leni is a Nazi', and I'll keep saying, 'But what did she do?'" She won more than 50 libel cases against people accusing her of knowledge having to do with Nazi crimes. Most of the negatives for Riefenstahl's finished films and other production materials relating to her unfinished projects were lost towards the end of the war. The French government confiscated all of her editing equipment, along with the production reels of Tiefland. After years of legal wrangling these were returned to her, but the French government had reportedly damaged some of the film stock whilst trying to develop and edit it and a few key scenes were missing although Riefenstahl was surprised to find the original negatives for Olympia in the same shipment.

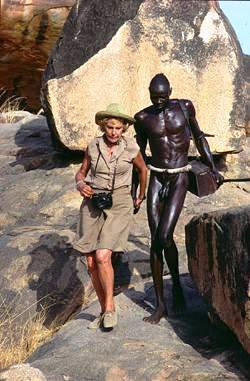

She had new ideas for Africa that saw her stretching herself artistically because she "was seeking in Africa was something far more then the romanticized version presented in Hemingway’s writing. She was looking for a total escape from the pressures of civilization, with its noisy and building cities, scandal-seeking newspapers, and corruption. The photojournalist George Rodger had first celebrated the ceremonial wrestling matches of the Nuba and, inspired by his work, Leni Riefenstahl made a number of lengthy visits to a people comparatively untouched by the modern world. Knowing nothing of her past, they accepted her as a friend. The result was several fine books of photographs, including The Last of the Nuba (1974).

Sources:

The Third Reich Politics and Propaganda. Welch, David (1993). New Fetter Lane, London: Routledge. "Leni: The life and work of Leni Riefenstahl, by Steven Bach". The Independent. Mathews, Tom (2007) Fall Weiss by Slawomir Wucyna, published by Agencja Wydawniza 1997 Leni Riefenstahl: A Memoir by Leni Riefenstahl, Picador Reprint edition, 1995 The Holocaust Chronicle, Publications International LTD Deutsches Bundesarchiv Wiener Library USHMM

Copyright David Nash & Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T 2010

|