Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Holocaust Prelude Early Nazi Leaders Nazi Propaganda Nazi Racial Laws Sinti & Roma Kristallnacht The SS SS Leadership Wannsee

Prelude Articles Image Galleries | ||||||

Zbaszyn Deportation to the Border Town Camp – 1938

The town was first mentioned in historical sources from 1231, and it received its city charter before 1311. As a result of the Second Partition of Poland in 1793 it became part of the Kingdom of Prussia and was administered within South Prussia.

After the Napoleonic Wars, the town was within the Grand Duchy of Posen and later the Province of Posen. It became part of the German Empire in 1871. In 1918 it became part of the Second Polish Republic. In 1938 the town’s population stood at 5,400 which included 360 Germans and only fifty two Jews.

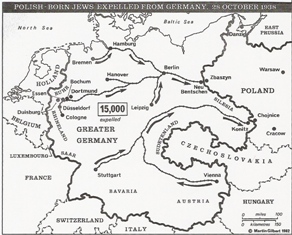

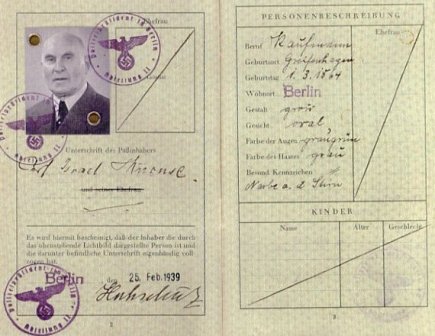

On the 27 October 1938 the Nazis began arresting Jews of Polish nationality in Germany with the intention of expelling them to Poland. The Nazis took this decision was the issuing of a decree by the Polish Ministry of the Interior on the 6 October 1938 which called for the passports of Polish citizens residing abroad would have to be checked and revalidated.

Those passports not re-validated by the 29 October 1938 would no longer entitle their holders to return to Poland. According to a report submitted by the Polish consulate in Opole (Oppeln in German) the German police came to the homes of the Jews at night to present them with the expulsion orders, forcing the Jews to get dressed at once and taking them to the Polish border which the Jews had to cross illegally.

Those expelled in this manner had no time to arrange their affairs or hand over their businesses. When they reached the border the German escorts often fired shots into the air in order to frighten the Jews even more and hasten their crossing over the border.

Expulsions took place all over the Reich, but the actions conducted by the police differed from location to location. Most often only the head of the family was expelled, but sometimes whole families were deported. The deportees were taken by train to the Polish border, usually in the vicinity of Zbaszyn and Beuthen. The Germans estimated that some seventeen thousand Jews were deported, but the precise figure may never be known.

The action by the Germans took the Polish authorities by surprise, and some Polish consulates, such as the one in Frankfurt am Main advised its Jews to comply with the German orders, while other consulates tried to help in various ways.

The Polish consul in Lipsk, Feliks Chiczewski permitted those destined for expulsion to take refuge in the building and garden of his office. In this way the expulsion of about half the Polish Jews in the city was foiled, according to German police estimates.

Local Polish authorities estimated the number of Jews expelled to the Zbaszyn district on the 28 and 29 October 1938 at 6100. Other estimates put the figure much higher as 12,000. The majority of those expelled from the Reich came by train, but large groups also arrived on foot, sometimes subjected to beatings as they were forced across the border onto Polish soil.

Among the deportees were elderly people, some who died during the journey, there were also cases of suicide and many of those who made it across the border had to be treated in hospital. One of the Jewish families caught up in this “aktion” were the Grynszpan family from Hannover, the father Zindel recalled the deportation:

“On the 27 October 1938 – it was Thursday night at eight o’clock – a policeman came and told us to come to Region II. He said, “You are going to come back immediately, you shouldn’t take anything with you. Take with you passports.”

When I reached the Region, I saw a large number of people, some people were sitting, some standing. People were crying, they were shouting, “Sign, Sign, Sign.” I had to sign, as all of them did. One of us did not, and his name, I believe, was Gershon Silber, and he had to stand in the corner for twenty-four hours.

They took us to the concert hall on the banks of the Leine and there, there were people from all the areas, about six hundred people. There we stayed until Friday night, about twenty-four hours.

Then they took us in police trucks, in prisoners’ lorries, about twenty men in each truck and they took us to the railway station. The streets were black with people shouting, “The Jews out to Palestine.”

After that, when we got to the train, they took us by train to Neubenschen on the German-Polish border. It was Shabbat morning, Saturday morning. When we reached Neubenschen at 6am there came trains from all sorts of places, Leipzig, Cologne, Dusseldorf, Essen, Bielefeld, Bremen. Together we were about twelve thousand people.

When we reached the border, we were searched to see if anybody had any money, and anybody who had more than ten marks, the balance was taken from him. This was the German law. No more than ten marks could be taken out of Germany. The Germans said, “You didn’t bring any more into Germany and you can’t take any more out.”

The SS were given us, as it were, protective custody, and we walked two kilometres on foot to the Polish border. They told us to go – the SS men were whipping us, those who lingered they hit, and blood was flowing on the road.

They tore away their little baggage from them, they treated us in a most barbaric fashion – this was the first time that I’d ever seen the wild barbarism of the Germans. They shouted at us, “Run! Run!” I myself received a blow and I fell in the ditch. My son helped me, and he said, “Run, run, dad – otherwise you’ll die.”

When we got to the open border- we reached what was called the green border, the Polish border- first of all, the women went in. Then a Polish general and some officers arrived, and they examined the papers and saw that we were Polish citizens, that we had special passports. It was decided to let us enter Poland.

They took us to a village of about six thousand and we were twelve thousand. The rain was driving hard, people were fainting – some suffered heart attacks. On all sides one saw old men and women. Our suffering was great – there was no food – since Thursday we had not wanted to eat any German bread.”

While at Zbaszyn, Zindel Grynszpan also recalled the Jews were put in stables still dirty with horse dung. A lorry with bread arrived from Poznan, but there was not enough bread to go round. Zindel Grynszpan sent a postcard to his other son Herschel in Paris, describing the horrors his family had experienced. Herschel enraged about the treatment his family and others had suffered shot the German diplomat Ernst vom Rath in Paris.

The Nazis used this as a pretext to launch the Kristallnacht pogrom, which saw synagogues and businesses burnt and looted, and Jews murdered or incarcerated into concentration camps. The deportees were only allowed to take ten Reichsmarks per person and no valuables or securities, so they were unable to travel further inside Poland, due to lack of funds.

During the initial phase of the expulsions the Polish police stopped groups of Jews who had entered Poland illegally and sometimes forced them back into Germany. At first, most of the expellees coming over the border near Zbaszyn were kept close to the point where they had crossed into Poland, but later on they were taken to Zbaszyn.

Some of the people were able to make their way into the Polish interior, particularly those who had relatives and friends, whilst those not so fortunate remained in the railway station, on a nearby lot, or in the streets. The Polish authorities put former stables at the disposal of the deportees. By the 31 October 1938 the police had listed 5,799 expellees arriving in Zbaszyn. On that day the central Polish authorities issued an order forbidden Jews to leave the town.

The Polish authorities hoped that the concentration of large numbers of Jews expelled from Germany near the border would exert pressure on the Germans and induce them to begin negotiations to hasten the return of the Jews back to their former homes. During the initial stage, the local inhabitants of Zbaszyn responded to the authorities appeal and provided the refugees with warm water and some food.

On the afternoon of the 30 October 1938 help arrived from Warsaw supplied by Emanuel Ringelblum and Yitzhak Gitterman of the Joint Distribution Committee, who were to form the General Jewish Aid Committee for Jewish Refugees from Germany in Poland, established several days later on the 4 November 1938.

A committee to help the refugees was also set up in Zbaszyn headed by a Jewish flour-mill owner named Grzybowski. The refugees were housed in army barracks and in buildings forming part of the flour mill, and fifteen hundred of them were accommodated in private dwellings. Expenses were met by the aid committee.

The restriction on the movement of the refugees, confining them to Zbaszyn, was a violation of their civil rights and led to protests. Some managed to escape, in spite of the precautions taken by the police, at times with the help of local inhabitants.

The Polish authorities did not consider the ban on some refugees leaving Zbaszyn as anything other than a temporary measure, and when negotiations with the Germans dragged on, the refugees were issued permits to leave the town. At the end of November 1938 the Polish authorities decided to close down the camp in stages, at the time there were approximately four thousand refugees in Zbaszyn.

The refugees sought out relatives and friends in Poland and many Jewish communities rallied to their aid. Some of the refugees obtained emigration visas and left the country. A number of young people joined the agricultural training camps of the He-Haluts Zionist movement.

The expenses of maintaining the camp were borne by a national committee supported by local committees were significant 2.8 million zloty and by the Joint Distribution Committee 700,000 zloty.

A number of institutions were formed in the camp to serve the refugees, by a delegation from the national committee and the Joint Distribution Committee working in co-operation and headed by Emanuel Ringelblum.

They provided the refugees needs and gave support to the local offices, which could not have handled all the many requirements on their own. The camp was run by a main office, with sub-offices for supplies, housing, legal affairs, information, registration, emigration, postal and employment, children, cultural activities, welfare, health, supervision and control and a court of honour.

A fifty-bed hospital was established, as were a dental clinic and a first-aid station , workshops, vocational and language courses, classes for children and even sports clubs, which played local Zbaszyn teams.

Ringelblum in a letter written on the 6 December 1939 described the period he spent in Zbaszyn working with the refugees, which demonstrated just how much was achieved:

Negotiations between the Polish authorities and the Germans came to an end on the 24 January 1939, when an agreement was signed under which the deportees were allowed to return to Germany, in groups not exceeding one hundred at a time, for a limited stay to settle their affairs and liquidate their businesses.

The proceeds of such liquidation would have to be deposited in blocked accounts in Germany from which withdrawals were practically impossible.

The Polish government, for its part, enabled the families of the deportees to join them in Poland. These arrangements took until the summer of 1939, and most probably, a small number of refugees were still on their temporary stay in Germany when the Germans invaded Poland on the 1 September 1939.

The Encyclopaedia of the Holocaust

Copyright: James Ardolin & Norbert Brenner H.E.A.R.T 2008 |