Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Holocaust Prelude Early Nazi Leaders Nazi Propaganda Nazi Racial Laws Sinti & Roma Kristallnacht The SS SS Leadership Wannsee

Prelude Articles Image Galleries | |||||

The Kindertransports

The history of the Kindertransports is a poignant tale of rescue, separation, loss and integration following the persecution of the Jews in the Nazi Reich and countries annexed by the Germans during the latter part of 1938.

Following the Kristallnacht outrage against the Jews on the 9 November 1938 as a response to what was happening to the Jews in the Reich a debate was held in the House of Commons as a direct result of an appeal by the British Jewish Refugee Committee.

The British Government had just refused to allow 10,000 Jewish children to enter Palestine, but with the atrocities in Germany, there was a change of heart, best expressed by the words of British Foreign Minister Samuel Hoare, “Here is a chance of taking the young generation of a great people, here is a chance of mitigating to some extend the terrible suffering of their parents and their friends.”

The British Government agreed to permit an unspecified number of children under the age of 17 to enter the United Kingdom. The children were allowed to enter the British Isles on temporary travel documents, with the belief that the children would re-join their parents at a later date, when things returned to normal. However it was private citizens or organizations had to guarantee to pay for each child's care, education, and eventual emigration from Britain. In return for this guarantee, the British government agreed to allow unaccompanied refugee children to enter the country on temporary travel visas. It was understood at the time that when the “crisis was over,” the children would return to their families.

Parents or guardians could not accompany the children. The few infants included in the program were tended by other children on their transport. A £50 Sterling bond had to be posted for each child, “to assure their ultimate resettlement.”

A number of people and organisations rose to the immense challenge of organising the transports, Jews, Christians and Quakers worked together to get the children out of Germany and the annexed territories.

The framework for the refugee operation was formed by Lola Hahn – Warburg several years earlier, Lord Baldwin, Rebecca Sieff, Sir Wyndham Deeds, Viscount Samuel, Rabbi Solomon Schoenfeld, who saved approximately 1,000 Orthodox children.

In addition Nicholas Winton rescued nearly 700 Jewish children in Prague, Professor Bentwich organiser of the Dutch escape routes and the Quaker leaders Bertha Bracey and Jean Hoare (cousin of Sir Samuel Hoare) who herself led a planeload of children out of Prague.

According to a scrapbook Winton kept, 664 children came to Great Britain on transports that he organized. In the research compiled for the documentary “The Power of Good: Nicholas Winton,” aired on Czech television in 2002, researchers identified five additional persons who entered Britain on a Winton-financed transport, bringing the official number to 669 children. The available information indicates that some children who were rescued have not yet been identified.

Worthy of mention Truus Wismuller - Meyer, a Dutch Christian who stood up to Adolf Eichmann in Vienna and brought out 600 children on one train, organised a transport from Riga to Sweden and helped smuggle a group of children onto the illegal ship Dora bound from Marseille to Palestine. She also was responsible for guiding the last transport through burning Amsterdam to the freighter Bodegraven in May 1940.

The first sealed train transport left Germany on the 1 December 1938, it arrived in Harwich from the Hook of Holland, carrying two hundred children, all of them orphans, who had left Germany with just twenty-four hours notice, each with two bags of clothing.

After the children's transports arrived in Harwich, those children with sponsors went to London to meet their foster families. Those children without sponsors were housed in a summer camp in Dovercourt Bay and in other facilities until individual families agreed to care for them or until hostels could be organized to care for larger groups of children. Many organizations and individuals participated in the rescue operation. Inside Britain, the Movement for the Care of Children from Germany coordinated many of the rescue efforts.

Among the German Jews who found refuge in Britain via the Kindertransports was Eric Lucas, who recalled his journey from Germany, his moving account deserves not to be abridged:

“The town where we lived was the border-control point, as beyond it stretched the still free towns of Belgium and Holland. In just over an hour the train would speed through the fertile lowlands of Belgium, and would take me right to the Channel Port of Ostend.

I was the only passenger who boarded the train at that station. To travel abroad, to leave the country was only granted to emigrants and those who had a special reason connected with the interest of the state.

The travellers were few, but the customs officials and the guarding soldiers were many. The men on whose whim hung one’s final leaving were the sinister tall figures in new black uniforms.

When I was at last allowed to board the train I rushed to the window to look for my parents whom I could not see until I had left the customs shed. They stood there, in the distance, but they did not come to the train.

I waved timidly and yet full of fear, after the control I had just passed, but even that was too much. A man in a black uniform rushed towards me, “You Jewish swine – one more sign or word from you and we shall keep you here. You have passed the customs.”

And so I stood at the window of the train. In the distance stood a silent and aging couple, to whom I dared neither speak nor wave a last farewell, but I could see their faces very distinctly in the light of the oncoming morning.

A few hours previously, first my father and then my mother had laid their hands gently on my bowed head to bless me, asking God to let me be like Ephraim and Menashe.

“Let it be well with you. Do your work and duty, and if God wills it, we shall see you again. Never forget that you are a Jew, do not forget your people, and do not forget us.”

Thus my father had said and his eyes had grown soft and dim, “My boy – it may be that we can come after you, but you will never be away from me – from your mother.”

Tears streamed down her infinitely kind and sad face. With a last effort she continued in the old, so familiar Hebrew words, “Go now, in life and peace.”

Standing at the window of the train, I was suddenly overcome with a maiming certainty that I would never see my father and mother again. There they stood, lonely and with the sadness of death. Cruel hands kept us apart in that last intimate moment. A passionate rebellious cry stuck in my throat against all that senseless brutality and inhuman cruelty.

"Why, O God had it all to be like that?"

There stood my father and my mother, an old man leaning heavily on his stick and holding his wife’s hand. It was the first and last time in my life that I had seen them both weep. Now and then my mother would stretch her hand out, as if to grasp mine – but the hand fell back, knowing it could never reach.

Can the world ever justify the pain that burned in my father’s eyes? My father’s eyes were gentle and soft, but filled with tears of loneliness and fear. They were the eyes of a child that seeks the kindness of its mother’s face, and the protection of its father.

As the train pulled out of the station to wheel me to safety, I leant my face against the cold glass of the window, and wept bitterly. Those who have crossed the Channel, escaping from fear of death to safety, can understand what it means to wait for those who are still beyond it, longing to cross it, but who will never reach those white cliffs, towering over the water.

Despite the best efforts by Eric Lucas to obtain a visa for his parents to come to England, he was not able to secure such a document, and four years later his parents perished.

The fate of Isaac and Sophie Lucas, was tragic, but not unique, probably Isaac was murdered in Auschwitz, but this cannot be confirmed for certain whilst recent research has revealed that Sophie was deported from Koblenz to Izbica on the 22 March 1942.

Sophie probably perished in the Aktion Reinhard death camps either at Belzec or Sobibor, but that may never be known for certain. The children arriving in Britain who had pre-arranged sponsors waiting for them were sent to London to be met and taken to their new homes.

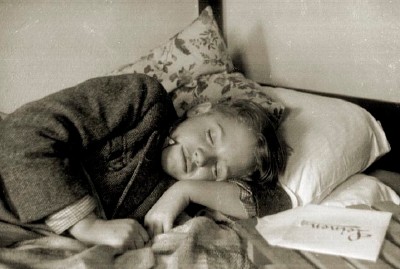

Those who did not have foster parents waited in Dovercourt, a summer holiday camp, and similar places until foster families came forward to look after them.

Many organisations and individuals helped settle the Jewish refugees into a new life in England including the Refugee Children’s Movement, the B’ Nai B’rith, The Chief Rabbi’s Religious Emergency Council, the Y.M.C.A. and Society of Friends. As well as individual donations of money, bedding and clothes, large property to serve as hostels were also made.

The children from the Kindertransports were dispersed to many parts of the British Isles, in private homes, boarding schools. Others lived in hostels and farms in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Those older than fourteen years of age, who did not go to boarding schools were often absorbed into Britain’s labour force, either in agriculture, or in domestic service. Some older children, as soon as they reached eighteen years of age joined the Allied armed forces, and played their part in defeating the Nazis.

After the war, many children from the children's transport program became citizens of Great Britain, or emigrated to Israel, the United States, Canada, and Australia. Many families, Jewish and non-Jewish opened their homes to take in these children, the vast majority were well treated, and close bonds were developed, some which were life-long. Most of these children would never again see their parents, who were murdered during the Holocaust.

In 1988 Bertha Leverton, herself a Kindertransport member, living in London planned a 50th anniversary local reunion of the Kindertransports and in June 1989, over 1,200 people attended from many countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia and other countries attended an international reunion.

The Kindertransports were a remarkable humanitarian venture approximately 10,000 children were rescued on the transports that commenced on the 1 December 1938, and the last one which left continental Europe on the 1 September 1939.

Sources:

Kindertransports Association (KTA) The Holocaust, by Sir Martin Gilbert, published by Collins London 1986 Die Juden Deportationen aus der Deutschen Reich, by Diana Schulle and Alfred B. Gottwaldt, published by Marixverlag 2005 Wiener Library USHMM Yad Vashem Holocaust Historical Society Private Collections

Copyright: Victor Smart, Chris Webb, & Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T 2009

|