Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Revolt & Resistance

Acts of Resistance

Jewish Resistance

Groups Jewish Resistors Allied Reports Anti-Nazi Resistance Nazi collaborators

| ||||

The Jews of Chelm & Escape from Borek Forest

Jews may have been present in Chelm in the 12th Century and contributed one of the largest and most important communities in Poland by the 16th Century. Over time the Jews of Chem inexplicably earned a reputation for simple –mindedness, giving rise to many entertaining stories and making Chelm or Chelmer bywords in the Jewish world.

Disaster struck the Jewish community in Chelm in the mid-seventeenth century, when one of Bogdan Chmielnicki’s armed Cossack units burst into the town, killing many Jews.

On the eve of the Second World War there were about 15,000 Jews in Chelm, by circa 1941/ 1942 the population according to Das General Government by Du Prel, was around 35, 000 made up of 18,000 Poles, 12,000 Jews and 5,000 Ukrainians.

The Germans occupied the city on 9 October 1939 immediately instituting a regime of severe persecution, such as the incident described below:

“In December 1939 several hundred Jews from Chelm were taken in trucks to Hrubieszow, where together with more than a thousand Jews from Hrubieszow they were forced to walk to the Soviet border.

The Jews were told that they would be going out to work. Many women and children tried to join their men-folk, not wishing to be separated from them, but were ordered to return home. Craftsmen, shoemakers and carpenters were ordered to lead the march.”

Hirsch Pachter recalled:

“We started marching, One girl succeeded in following the marchers, shouting “Father” all the way. At the first village, they took the girl away. We do not know what happened to her, but we heard a shot.”

The marchers were divided into about ten groups of two hundred men each. At the end of the first day’s march, on the evening of the 2 December, twenty Jews were taken out of Hirsch Pachter’s group – two rabbis, two synagogue beadles, and other people with long beards – they were never seen again. From the other groups, a further two hundred men were taken away.

Early on 3 December the march resumed. At the first village, three bearded Jews were lead away, Shmuel Topocostok, Benjamin Rosenberg and a man by the name of Loewenberg.

As Loewenberg was led away, Pachter later recalled, “his son jumped up, and said, “Leave my father alone, I will take his place. Take me,” and they said, “You come along too,” and they took both of them and the other two. Pachter added, “They were all shot in the back of their heads and the bullets came out of their foreheads.”

The third day of the march, December 4, saw further shootings, the Germans competing as to the number of Jews they could kill in a specific time. “They would lay a hand on a man. He would lie down – whoever did not want to lie down would be hit on the head with a rifle butt and the blood ran.

But most people were so tired that they could not resist. We were only shadows after all this marching. The slaughter on that day was horrible.”

Of the eighteen hundred Jews who had set off from Hrubesziow, more than fourteen hundred were murdered on that day. The surviving marchers had been given nothing to eat but a small bread roll each. Seeing a fifteen –year old boy without any food at all, a fellow marcher threw him a piece of his own roll. When the boy bent down to pick it up, he was shot, by the commander of the march himself.

“He shot him, Pachter recalled, “but he did not kill him, and he ordered another man to finish the job. The other one apologised in a way – as if to say that the boy had jumped out of line, and if he had not done that he would not have been shot.”

Two hundred marchers reached the Soviet border on the morning of December 9, starving and in pain from their torn and bleeding feet. “The sun was rising,” Pachter recalled, “We were told to sing.

Whoever would not sit down and sign would be shot. We started singing Jewish melodies. All day the marchers sat, and sang. That night they were taken to a bridge across the River Bug, which marked the border, and ordered to march across it, hands held high, shouting “Long Live Stalin.”

A Judenrat was then appointed and in October 1940 the Jews were confined to a ghetto, which was sealed in late 1941. Hunger and disease claimed many lives, deportations to the Belzec death camp commenced on the 11 April 1942.

Further deportations of the Jews of Chelm to Sobibor death camp commenced on 22 May 1942, when 3,000 Jews were packed into cattle cars and transported there for extermination, followed by 2,000 Jews from Slovakia who arrived in the ghetto on the same day.

On 28 May 1942 four Jews were executed by a German Security police firing squad, their last moments captured for posterity by an unknown German camera man, their crime unknown.

In June 1942 another 600 were sent to Sobibor as able bodied workers, and on 27 -28 October 1942, 3,000 Jews were led on a forced march to Wlodawa for deportation to Sobibor, very few survived.

The last Jews were sent to Sobibor death camp where they were exterminated on the 6 November 1942.

Borek Forest

The Germans established prisoner of war camps for Russian soldiers on Lwowska Street, Chelm and Italian soldiers were also imprisoned there after Italy abandoned the Nazi cause. The Germans murdered an estimated 30,000 Soviet Prisoners of War and Italian Prisoners of War and buried them in the Borek woods, near Chelm.

Josef Reznik, a Jewish soldier in the Polish army, had been incarcerated in Majdanek, and then was taken to the Lipowa Street camp in Lublin, was taken back to Majdanek in November 1943 to be murdered as part of the Aktion Erntefest.

He was selected along with 300 other men by SS- man Rolfinger, and taken to the Borek forest to exhume the bodies and cremate the corpses as part of the Sonderkommando 1005.

At the Eichmann trial in 1961 Reznik testified as to the conditions as to which he and his fellow prisoners worked and lived in Borek forest:

“There they took us to pits, to some sort of trenches. I was digging with my spade. I hit the earth once or twice, and all at once the spade slipped and I realised that the spade had struck a human head, and such an evil smell came out of the earth. Then Rolfinger screamed at me and said, “Why did you stop? Don’t you know there are bodies lying there?”

There in the first trench, which was 150 or 170 metres in length, there were about ten thousand corpses. They brought a mill for grinding the bones. Our people sifted the bones, so that the gold could be extracted, if there were any in the teeth. Rolfinger and his deputy Raschendorf, SS men from Chelm, took all the gold.

The bones were brought to the grinding machine, and the ground bones were later brought to the fields and scattered there. There was such a stench that one could not keep one’s mouth open.

We worked for three months, there were eight or nine graves, I cannot tell exactly, and one trench they kept open for more people. All that time, they were bringing in new people in trucks. The persons that were brought, the dead bodies – I do not know whether it was from gas or from the air- were still warm, with no clothes, like Adam and Eve.”

The Germans used gas vans in the Chelm area, stationed at the Gestapo office in Chelm, possibly these vans were also kept at Majdanek near the SS garage.

Reznik described what he saw when he opened one grave:

“We were digging in one of the trenches and took out a certain number of corpses. The number was reported to Rolfinger who supervised the work. He looked at his notes and said, “Here five or eight more Jews are still missing. You must dig and find them.”

So I put in the spade again, and suddenly a wall collapsed, and there was another seven or eight corpses, and next to one of them was a ritual slaughterer’s knife, and he still wore the Star of David. Rolfinger knew exactly how many corpses were in each trench.

After removing the bodies, chloride was spread in the pits. We filled the pits and we put soil on top. Over these pits, after filling them up, we also sowed grass. The corpses were burned, one thousand at a time. There were two such stacks for burning, such a mound of corpses burned for two or three days.

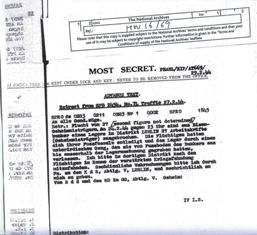

Reznik described his escape - this German police decoded message about the escape was intercepted by the Allies at their Bletchley Park British Intelligence complex, the escape took place during the night of 24 February 1944.

“We were put in fetters in our hut. In all four corners were machine guns. For every sixty or sixty-five of us, there were forty-five Security Police, not counting the SS who were there. And later, they put chains on us, each one ninety centimetres long, with shackles around our legs.

We were deep down in a bunker, with a heavy iron door on it, barred with a heavy iron bolt – all this to prevent our escape. We dug a tunnel, at a depth of 2.10 meters, fifty metres in length. This took us over two months of work, and the tunnel led to a new trench which was to receive fresh corpses.

Our chains were inspected every day, one day immediately after the inspection we decided to break our chains. I do not want to brag, I broke the chains of eight men, with a kind of tool that could twist the chain, and it broke.

Many ran away with the shackles on their legs. I managed to remove the shackles and fled through the trench. I remained alone. Four people saved themselves.”

Today at the site of the mass murder and cremation site there is a large memorial for the Soviet Prisoners of War and a smaller one for the Italian Prisoners of War murdered there.

Sources:

Eichmann Trial Transcripts – Nizkor Holocaust Journey by Sir Martin Gilbert published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson London 1997 Holocaust Historical Society Das General Gouvernement by Dr Max Freiherr Du Prel, published by Konrad Triltsch Verlag Wurzburg National Archives – Kew

Copyright: CW H.E.A.R.T 2008

|