Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Revolt & Resistance

Acts of Resistance

Jewish Resistance

Groups Jewish Resistors Allied Reports Anti-Nazi Resistance Nazi collaborators

| ||||||||

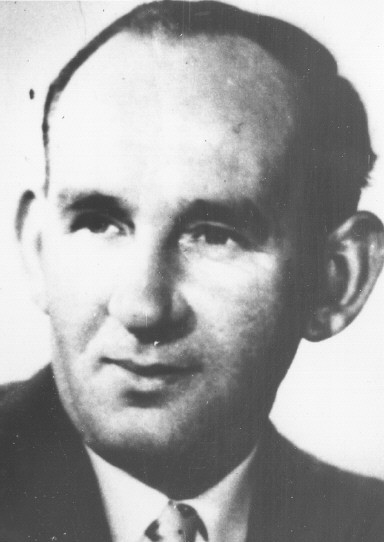

Alexander Pechersky Leader of the Sobibor Revolt Testimony

I was born in Kremenchug in 1919, but spent my childhood in Rostov. After I finished my secondary studies I entered a music school. Music and theatre were the most important things in my life. I directed amateur dramatic circles and took a great interest in the arts.

In 1941 I joined the army with the rank of second lieutenant, and was soon promoted to first lieutenant. Taken prisoner in October 1941, I caught typhus, but concealed the disease, fearing to be killed.

In May 1942, I tried to escape with four other prisoners, but we were caught and were sent first to the disciplinary camp of Borysov and then to Minsk. During a medical examination it was discovered that I was Jewish. I was locked up with other Jews in a place nicknamed “the Jewish cellar,” where we spent ten days in complete darkness.

We were allowed 100 grams of bread a day and a jug of water. Then on September 20 1942 we were transferred to the labour camp of Sheroka Street in Minsk, where I lived until my deportation to Sobibor.

In September 1943 we were told that Jews would be transferred to Germany, but that families would not be separated. At 4am a silent crowd left Minsk, the men on foot, women and children in trucks.

We gathered at the railway station where a freight train awaited us. Seventy people were crowded into a box-car, and after four days we reached Sobibor. We stopped during the night and were given water. The doors opened, and facing us, was a poster Sonderkommando Sobibor.

Tired and hungry, we left the car. Armed SS officers stood there and Oberscharfuhrer Gomerski shouted “Cabinet makers and carpenters with no families forward.”

Eighty men were led into the camp and locked in a barrack. Older prisoners informed us about Sobibor. We had all fought in the war and suffered in labour camps but we were so horrified about Sobibor that we could not sleep that night.

Shlomo Leitman, a Polish Jew from Sheroka, was lying at my side. “What will become of us?” he asked. I didn’t answer pretending to sleep. I couldn’t get over my reaction and was thinking of Nelly, a little girl who travelled in my boxcar and who was, no doubt, dead already. I thought of my own daughter Elochka.

On September 24, I wrote in my diary: “We are in the camp of Sobibor, we rise at 5.00 am, get a litre of warm water, but no bread, at 5.30 we are counted, at 6.00 we leave for work, in columns of threes, Russian Jews are in front, then Poles, Czech and Dutch.”

I remember when the SS man Frenzel ordered us to sing, Cybulski was walking at my side, “What shall we sing?” he asked and I answered, “We only know one song: Yesli Zavtra Voyna.” It was a patriotic Russian song and it gave us hope for freedom.

Soldiers led us to the Nordlager, a new section of the camp. Nine barracks were already built there and others were under construction. Our group was split in two, one part was sent to build, the other to cut wood. On our first day of work, fifteen people got twenty-five lashes each for incompetence.

On September 25, we unloaded coal all day and were given only twenty minutes for lunch. The cook* was unable to feed us all in such a short time. Frenzel was furious and ordered the cook to sit down. Then he whipped him while whistling a marching tune. The soup tasted as though it had been mixed with blood and although we were very hungry, many of us were unable to eat.

Our arrival at the camp made a great impression on the older prisoners: they knew well that the war was going on, but had never seen the men who fought in it. And these newcomers could handle arms!

We were approached by men and women who made us understand that their wish was to get out of hell. I couldn’t speak Yiddish so Shlomo Leitman who was born in Warsaw, acted as interpreter. We could understand some Polish as it resembles Russian.

I wanted to know the topography of Sobibor. Camp Number 1 where we lived, included workshops and kitchens. Camp Number 2 the reception centre of the new arrivals, had storage for the belongings stolen from the prisoners , a corridor led to Camp Number 3 and its gas chambers.

On September 26, twenty-five prisoners were whipped, a young Dutchman tall and lean, was chopping wood, but was not strong enough for the task. The SS guard hit him on the head. Astonished I stopped working. Furious, the guard shouted, “I give you five minutes to chop this wood, if you fail, you will get twenty-five lashes.”

I hit the wood as though it were his head. “You did it in four and a half minutes,” said the Nazi looking at his watch. He offered me a cigarette. “Thanks, I don’t smoke,” I replied.

27 September. We were still working at the Nordlager. At 9 a.m. Kali-Mali, from Sheroka, whose real name was Shubayev, told me, “All the Germans have left, only the Kapo is here, why?”

I answered, “I don’t know, but let us see where we are.” A prisoner informed us, “If they are not here, it means that a convoy has just arrived, look over there at the Camp Number 3.” We heard a terrible scream from a woman, followed by children wailing, “Mother, mother.” And, as if to add to the horror, the bawling of geese joined the human wailing.

A farmyard was established in the camp to enrich the menus of the SS men, and the bawling of the geese covered the shrieks of the victims.

My helplessness at these crimes horrified me, Shlomo Leitman and Boris Cybulski were livid, “Sasha, let us escape, we are only 200 metres from the forest, we can cut the barbed wire with our axes and run,” said Boris. “We must escape all together and soon: winter is near and snow is not our friend,” he added.

On September 28, one week after I arrived at the camp, I knew everything about the hell of Sobibor. Camp Number 4 was on a hill: each section was surrounded with barbed wire and was mined. I was informed of the exact place occupied by the personnel, the guards and the arsenal.

Next day, the 600 prisoners, men and women were taken to the station to unload eight cars of bricks. Each of us was forced to run and fetch eight bricks; the one who failed was whipped twenty-five times. We finished our work in less than an hour and we returned to our commando’s. The reason for the haste, a new convoy was just entering the station.

Our group of eighty men was finally led to Camp Number 4, I was working near Shlomo; another prisoner from Sheroka approached me and whispered, “We have decided to escape; there are only five SS officers, and we can wipe them out. The forest is near.”

I replied, “Easier said than done, the five guards are not together. When you finish with one, the second shoots at us; and how shall we cross the minefields? Wait the time is near.”

At night, Baruch (Leon Feldhendler)** told me, “It is not the first time that we have planned to finish with Sobibor, but very few of us know how to use arms. Lead us, and we shall follow you.” His intelligent face inspired trust and gave me courage. I asked him to form a group of the most reliable prisoners.

On October 7, I gave to Baruch (Feldhendler) my first instructions on how to dig a tunnel. “The carpenters’ workshop is at the end of the camp, five metres from the barbed wire; the net of three rows of barbed wire occupies four metres to fifteen metres; let us add seven metres, the length of the barrack.

We shall start digging under the stove and the tunnel will be no more than thirty-five metres long and eighty centimetres deep, because of the danger of mines. We shall have at least twenty cubic metres of earth to hide, and shall leave that earth under the floorboards. The job must be done only at night.”

We all agreed to start working: the digging of the tunnel would take us fifteen to twenty days. But the plan presented weak spots: between 11pm and 5am six hundred persons had to pass in Indian file the thirty-five meters of the tunnel and run a good distance from the camp in order to avoid the posse of the SS.

I said, “I also have other ideas, meanwhile, let us prepare our first arms: seventy well whetted knives or razor blades.” Barauch (Feldhendler) said that the Kapo’s were interested in our plans and could be very helpful, since they walked freely in the camp. I thought that their help was vital, “All right, I accept,” I said.

October 8 1943. A new transport arrived. Janek, the carpenters’ supervisor, needed three prisoners to help him. Shlomo, another prisoner and I were chosen and sent to Camp Number 1. That same evening, Barauch (Feldhendler) brought Shlomo seventy well whetted knives.

October 9: Grisha, who was caught sitting while cleaning wood, got twenty-five lashes. It was a bad day, thirty of our people had been flogged for various transgressions and we were exhausted. In the evening Kali-Mali came to the barracks, out of breath.

He informed me that Grisha and seven of our men were ready to escape and asked us to join them. “Come with us, the site near the barbed wire is badly lit, we will kill the guard with an axe and then we will run to the forest.” We went to find Grisha, and I explained to him that reprisals would be terrible even if his plan succeeded. I had to use threats before I persuaded him to plan only a collective escape.

October 10: I saw an SS officer with his arm in a sling. I was told that it was Greischutz back from his leave. He had been wounded in a Russian air raid. Later, Shlomo an I met the Kapo Brzecki*** who knew that we were preparing something. “Take me with you; together we shall accomplish more. I know the end awaits us all,” he said, and he also asked us to include the kapo Geniek. I answered, “Could you kill a Nazi?” He thought for a moment, and replied, “Yes, if it is necessary for our cause.”

October 11: That morning, we heard screams followed by shots. We were locked up in the barracks and guards stood around us. The shooting lasted a long time and seemed to be coming from the Nordlager. We feared the prisoners had tried to escape before we were ready. Soon we learned the cause of the fusillade, a group of new prisoners already undressed, had revolted and had tried to run in the direction of the barbed wire.

The guards began to shoot and killed many of them instantly. The others were dragged to Camp Number 3. That day, the crematorium burned longer than usual. Huge flames rose up in the grey autumn sky and the camp was lit with strange colours. Helpless and distressed, we looked at the bodies of our brothers and sisters.

October 12: It was a terrible day: eighteen of our friends, many from Sheroka, were sick. Several SS men, under the direction of Frenzel, entered our barrack and asked the patients to follow them. Among them was a young Dutch prisoner with his wife, and the unfortunate man could hardly walk. The woman was running after the group screaming, “Murderers, I know where you are taking my husband. I can’t live without him! Assassins, murderers.” She died with the group.

Shlomo and I ordered a meeting for 9.00 pm, at the carpenters’ workshop. Baurach (Feldhendler) Shlomo, Janek, the tailors Joseph and Jacob, Moniek and others were present. We posted a sentry at the entrance. Moniek went to fetch Brzecki and, when both returned, I asked Brzecki again if he had thought over the consequences of his decision; if the plan failed, he would be the first to die.

He said, “I know it, but we must get rid of the SS officers and this should take one hour, if we could do it in less time, so much the better. For that purpose, we need efficient and determined men, since one moments hesitation would be fatal, and I know some capable people, who can do the job.”

At 3.00 pm Brzecki was to lead three of his men to Camp Number 2 under any pretext that he would find himself. Their task would consist of liquidating the four officers present. Baurach (Feldhendler) would lead the SS men to a place where the prisoners would be waiting, and would prevent anyone from leaving Camp Number 2 once the action had begun.

At exactly 4 o’clock, another team would cut the telephone wires from Camp Number 2 to the guards’ quarters. The same team would hide those wires in such a way as to make it impossible to reconnect the telephone on the same day. At the same time, we were to start killing SS officers, they would be invited, one by one, into the workshops where two of our men would execute them. At 4.30 pm everything would be finished.

At the same time Brzecki and Geniek would assemble the prisoners for the usual evening roll call. In front would be the Soviet prisoners who were to take over the arsenal and the rest of us would cover them. Once the arsenal was open, armed men would head the group and kill the guards at the gate. If they resisted we would fight with the arms taken from the officers.

Near the workshops and the officers’ villas was a mesh of barbed wire. There the ground was mined, but less dangerous. Stones were to be thrown in order to destroy the mines.

These were the details of the plan: I added that I had long discussions with Shlomo and I couldn’t think of anything better. I asked everybody to think it over again, and a new meeting was planned for the next day, under the strictest secrecy.

Just before the revolt, an idea occurred to me and I wanted to check if it was right. Having observed the behaviour of the guards for a long time, I knew that every morning each of them got five bullets for his rifle. I also noticed that, with the changing of each guard, the bullets were handed over to the next guard. This meant that the guards who were not on duty had no bullets.

In order to check my findings, I asked Brzecki to find an excuse to send me to the guards’ barracks. On October 13 at 10.00am, the carpentry workshop got an order to send a man to the barracks in order to repair the doors. Janek sent me there and, while I was visiting the rooms, I was glad to see that my idea was correct.

October 14: “On the night of October 13 we distributed knives and hatchets, as well as warm clothes.” I was to remain in the carpentry workshop where, from the window, I could watch what was happening in Camp Number 3. In the next barrack, Shlomo and a team of twenty men were repairing our wooden beds.

According to our plan, at 4.00 and at 4.15 pm, two SS men were to appear at the tailors’ workshop. At the same time, two officers Greischutz and Getzinger **** were in another workshop. Frenzel was supervising the building of some cupboards.

Rosenfeld’s job was to kill him. Friedrich Gaulstich would enter the carpentry workshop where Shlomo would be waiting. Other SS officers of Camp Number 2 were to be enticed into different workshops.

Each of us had his task: Shubayev, aged twenty-five, a railway engineer from Rostov, a good and simple buddy, would go to the tailors’ workshop with Moniek. Cybulski, a thirty-five year old driver, a former truck driver from Donbass, and accompanied by Michael and Bunio. Guided by Brzecki, they were to go to Camp Number 2 to meet Barauch (Feldhendler).

At 2pm, SS Unterscharfuhrer Walter Ryba came to Brzecki, he had a machine gun, and that worried me. That morning Frenzel noticed that Janek was better dressed than usual, but Geniek reassured us. Brzecki had to go to Camp Number 4 with other prisoners in order to stack wood. The guard took his machine gun only because he was the sole supervisor.

Geniek was to lead the four men to Camp Number 2. At first he asked us to postpone it to the next day, but that was impossible. Although the details of our plan were known only to the committee and a small group, the other prisoners felt that something was going to happen and kept asking: “Well, when will it be?”

On the eve of October 14th, the older people said prayers, it was Yom Kippur, the day of Atonement. ***** Some inmates told them, “Better pray for Sasha to help you.” They answered, “We are praying to God to help Sasha.”

We had another reason for not postponing our plan: On October 14 Gomerski was on vacation. The Lagerfuhrer Frenzel was a bastard but, compared to Gomerski, he seemed a choirboy. “Tomorrow may be too late,” I said to Geniek, “we have to do what we decided, and you must obey.”

At 3.20pm Geniek came to Cybulski’s barrack with Shlomo and the two others. Two officers were killed by Wajspapier in the shoemakers’ barrack while Jacob was giving them their boots. At 4.15 I heard that Cybulski, Michael and Barauch (Feldhendler) had accomplished their mission at Camp Number 2. At 4pm I had met Luka, the Dutch girl****** and told her, “The officers will soon be dead, be ready to escape.” As she trembled, I added, “What we are doing is the only way to survive, we have no right to give up living, we must avenge ourselves.”

At 4.30pm, Brzecki returned from Camp Number 4 with the commando and Unterscharfuhrer Gaulstich arrived soon afterwards. Shlomo told him, “We have done the repairs in the barracks, now the workers do not know what to do.” The SS man went in: Shlomo’s hatchet awaited him.

Frenzel didn’t come, and later we learned that SS officer Ryba had been killed in the garage. Now it was vital to leave, Brzecki whistled and prisoners were directed to Camp Number 1 in a disorderly way. This infuriated the guard, a Volksdeutsch from the Volga region, he was killed with an axe.

A new group coming from Camp Number 2, entered Camp Number 1 where prisoners were just learning what was happening. A Ukrainian guard began to shoot, a mighty “Hurrah” was heard. “Forward, Forward shouted the prisoners.

They were running towards the gate, shooting with rifles, cutting barbed wire with pliers. We crossed a minefield and many lost their lives. My group marched towards the quarter where the SS lived, and several of us were killed. Between the camp and the forest there was an immense clearing and here, too, many fell.

At last, we got to the forest, but Shlomo and Luka were missing. We walked all night in a column, one by one. I was up front, followed by Cybulski, while Arkady brought up the rear. We were all silent, from time to time, a light was visible in the sky.

After walking three kilometres we reached a canal, that was five or six metres wide and quite deep. Suddenly we saw a group of men. Arkady went crawling off to investigate. He found Shubayev and many other friends. Together we built a bridge with tree trunks, and then I learned that Shlomo had been wounded while escaping. Unable to run, he asked to be put to death. Of course nobody listened to him and he stayed behind with other prisoners.

Our group numbered fifty-seven people. After walking another five kilometres, we heard the noise of a train. We were on the edge of a wood, an area of bushes in front of us. Dawn was approaching and we needed a safe place to hide. I knew the Nazis were after us and we thought that a group of trees near a railway wouldn’t attract the attention of our enemy. We decided to remain there during the day, camouflaged by branches.

At dawn, it was raining. Arkady and Cybulski left to explore the terrain on one side, Shubayev and I on the other. We found an abandoned site near the forest. Cybulski and Arkady reached the railway line. Poles were working there, but without a guard. We hid and posted two sentries nearby; these sentries were to be changed every three hours. All day, planes were flying over our heads. We heard the voices of the Polish workers.

At night, we saw two men looking for something, we understood that they were fugitives who had returned from the direction of Bug, “Why haven’t you crossed the river?” I asked. They told us that they had been near a village where they learned that soldiers were sent along the Bug River to check all points.

I asked if they had met Luka, and they assured me that they had seen her in the forest, leaving for Chelm with Polish Jews. We formed a new column, Cybulski and I leading, Arkady and Shubayev in the rear. After five kilometres we reached the forest, but we couldn’t find enough food so we decided to split into small groups, each taking a different direction. My unit included, Shubayev, Cybulski, Arkady, Michael Itzkovich and Simon Mazurkewich.

We set off eastwards, guided by the stars. We walked at night, and hid during the day. Our objective was to cross the Bug River. We approached little villages to beg for food and to ask our way. We were often told, “Prisoners escaped from Sobibor where people are being burned, they are looking for fugitives.”

We reached the village of Stawki, a kilometre and a half from the Bug River. We had spent the day in the forest and, at sunset, three of us entered a hut. A thirty- year old peasant was cutting and gathering tobacco leaves, an old man was near a stove. In a corner, a baby’s cradle was hanging from the ceiling, and a young woman was rocking it. “Good evening, may we come in?”

“Come in, come in,” answered the young man. “Draw the curtains,” said Cybulski. We sat down, everyone was quiet. “Could you tell us where to cross the Bug?” asked Shubayev. “I don’t know,” said the young man. “You must know, you have been living here long enough. We know that there are places where the water is low, and the crossing easy.” I said. “If you are so sure, then go. We know nothing, and we have no right to go near rivers.”

We talked a little longer, and told them that we were escaped war prisoners and wished to return home. At last the young man said, “I shall show you the direction, but I won’t go to the river. Find it yourselves, be careful, it is guarded everywhere since prisoners escaped from a camp where soap is made with human fat. The fugitives are being chased everywhere, even underground. If you are lucky, you will get to the other side. I wish you luck.”

“Let’s go before the moon rises.” “Wait” said the young woman, “take some bread for the way.” We thanked them and the old man blessed us with the sign of the cross. The same night, October 19 we crossed the Bug. On the 22nd, eight days after the uprising, we met a unit of partisans of the Voroshilov detachment.

A new chapter began.

Notes:

* The cook was Herz Cukerman

** Baurach – this was Leon Feldhendler

*** Brzecki was probably Kapo Pozycki who died in the revolt.

**** SS- Oberscharfuhrer Anton Getzinger was not killed in the revolt, he died some weeks before the revolt, in an accident in the Nordlager. Graetschutz and Gaulstich were killed during the revolt.

***** It was not Yom Kippur it was Sukkoth

****** Luka was in fact from Hamburg, Germany, her fate is unknown, but it is unlikely she survived the aftermath of the revolt.

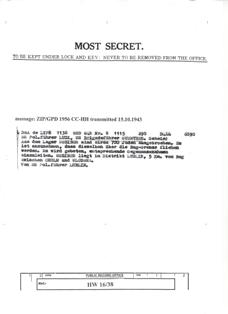

Sources:

Sobibor – Martyrdom and Revolt by Miriam Novitch published by the Holocaust Library New York 1980. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka by Yitzhak Arad, published by Indiana University Press 1987 Hidden Letters published by Star Bright Books 2008 Bilsky, Leora. "Judging Evil in the Trial of Kastner", Law and History Review, Vol 19, No. 1, Spring 2001 Russian Federation Archives

Copyright: Chris Webb & Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T 2008

|