Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Revolt & Resistance

Acts of Resistance

Jewish Resistance

Groups Jewish Resistors Allied Reports Anti-Nazi Resistance Nazi collaborators

| ||||

Rudolf Vrba "I escaped from Auschwitz"

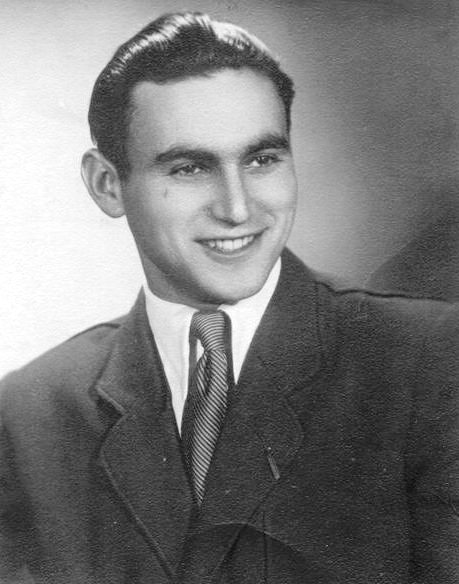

Rudolf Vrba was born as Walter Rosenberg in Topolcany, Czechoslovakia in on September 11, 1924 as the son of Elias Rosenberg (owner of a steam saw-mill in Jaklovce near Margecany in Slovakia), and Helena neé Grunfeldova of Zbehy, Slovakia. At the age of fifteen he was excluded from the High School (Gymnasium) of Bratislava under the so-called "Slovak State's" version of the Nuremberg anti-Jewish laws and forced to study at home.

On June 14th, 1942, he was deported first to Majdanek where he met with his brother "Sammy" who would later be murdered there. After being "duped" into volunteering for what was represented as a "Work Farm" assignment he was was transferred to Auschwitz on June 30, 1942. After six months in Auschwitz, he was transferred to Birkenau (Auschwitz II) and had the number 44070 tattooed on his arm.

The "Farm Work" consisted of excavating the bodies (for later burning), of over 100,000 prisoners that had already been murdered and buried at Birkenau. This horrific labour almost took his life, however his luck changed when a Viennese prisoner, trusted by the SS, discovered he could speak German and transferred him to a store-room, named Canada, where the clothing and belongings of the dead were sorted.

Although severely beaten after being caught smuggling some goods to friends, Vrba rose to become a camp registrar, and it was in this role he began to calculate and "mentally record" the figures of those transported to, and murdered in the camp.

Vrba met a fellow prisoner by the name of Alfred Wetzler, Wetzler was 24 years old at the time and the two men became extremely close friends. The men came to trust each other implicitly and decided to try to escape together.

With the help of the camp underground, at 2 p.m. on Friday, April 7, 1944 the two men climbed inside a hollowed-out hiding place in a wood pile that was being stored to build the "Mexico" section for the new arrivals. It was outside Birkenau's barbed-wire inner perimeter, but inside an external perimeter the Nazi guards kept erected during the day. The other prisoners placed boards around the hollowed-out area to hide the men, then sprinkled the surrounding area with a strong smelling Russian tobacco that was soaked in petrol, then dried and would help to keep the guard dogs away. This was a trick they had learned from a Russian POW Dmitry Volkov, who had escaped Auschwitz but had been recaptured.

Two weeks after escaping from Auschwitz, on April 24, 1944, Vrba and Wetzler met up with members of the Slovakian underground Working Group, or Jewish Council. The head of the Working Group, Dr. Oskar Neumann, a German-speaking lawyer, placed the men in separate rooms and asked them to begin writing down and describing their accounts. Eleven days after escaping, Vrba and Wetzler crossed the Polish-Slovakian border. They met a farmer who put them in touch with a Jewish doctor, Dr. Pollack, who had a contact, Adre Steiner, in the Slovak Judenrat (Jewish Council) in Žilina, which now called itself the Working Group, and regarded itself as an underground movement.

Vrba and Wetzler spent the night in Čadca in the home of Mrs. Baeck, a relative of the well-known rabbi Leo Baeck, and met the Working Group the next day, April 24, 1944. The head of the Working Group, Dr. Oskar Neumann, a German-speaking lawyer, placed the men in different rooms in a former Jewish old people's home, and interviewed them separately over three days.

Vrba believed that many of the 437,000 Hungarian Jews sent to Auschwitz between May 15 and July 7, 1944 — when 12,000 Jews were being dispatched by train every day — would have resisted or hidden had they known they were to be killed and not resettled.

He later wrote in his memoirs:

"From the testimony of survivors such as Elie Wiesel, it seems clear that the Jewish masses assumed that if something truly horrible was in store for them, these respectable leaders would know about it and would share their knowledge ... It is my contention that a small group of informed people, by their silence, deprived others of the possibility or privilege of making their own decisions in the face of mortal danger."

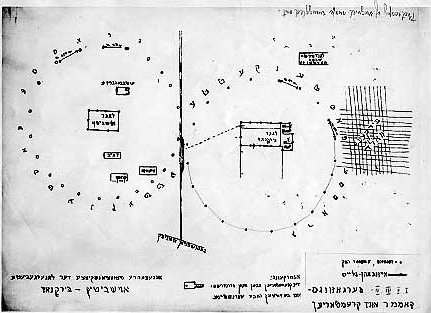

After handing being interviewed, Vrbda and Wetzler compiled a full report complete with sketches and drawings of the camp topology and crematorium. This report was turned over to the Slovakian Jewish Council, and Vrba felt his job was over.

The report was written and re-written several times. Wetzler wrote the first part, Vrba the third, and the two wrote the second part together. They then worked on the report together, and ended up re-writing it six times As they were writing it, Dr. Neumann's aide, Oscar Krasniansky, an engineer and good stenographer, who later took the name Oskar Isaiah Karmiel, translated it from Slovak into German with the help of Gisela Steiner, producing a 32-page report in German, which was completed by Thursday, April 27, 1944.

Vrba and Wetzler spent the next six weeks in Liptovský Mikuláš, and continued to make and distribute copies of their report whenever they could. The original Slovak version of the report was not preserved, according to Czech historian Miroslav Kárný. The German version contained a precise description of the geography of the camps, their construction, the organization of the management and security, how the prisoners were numbered and categorized, their diet, the selections, gassings, shootings, injections, and deaths from the living conditions themselves.

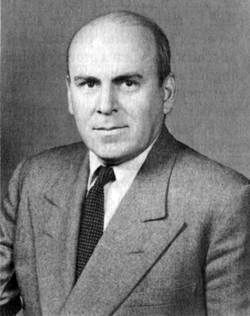

On 29th June, 1944, the 32-page Vrba-Wetzler Report was sent to John McCloy, former legal counselor to the major German chemical combine I. G. Farben, and was the Assistant Secretary of War from 1941 to 1945. Attached to it was a note requesting the bombing of vital sections of the rail lines that transported the Jews to Auschwitz. McCloy investigated the request and then told his personal aide, Colonel Al Gerhardt, to "kill" the matter. McCoy received several requests to take military action against the death camps. He always sent the following letter: "The War Department is of the opinion that the suggested air operation is impracticable. It could be executed only by the diversion of considerable air support essential to the success of our forces now engaged in decisive operations and would in any case be of such very doubtful efficacy that it would not amount to a practical project." In August, 1944, Leon Kubowitzki, an official with the World Jewish Congress in New York, passed on an appeal from Ernest Frischer, a member of the Czech government-in-exile, to take military action against the concentration camps. McCloy rejected the idea as it would require "diversion of considerable air support" and "even if practicable, might provoke even more vindictive action by the Germans."

Vrba wrote in his memoirs that, as the Germans were preparing the mass deportations to Auschwitz, the Jewish communities in Slovakia and Hungary placed their trust either in the Zionist leadership (people such as Rudolf Kastner, the de facto head of the Aid and Rescue Committee), or in Orthodox Jewish leaders, such as Rabbi Weissmandl and Philip von Freudiger.

The Nazis were aware of this, which is why they lured precisely those members of the community into various negotiations, supposedly designed to lead to the release of some, or even most, of the Jews, but probably regarded by the Nazis as a way of placating the Jewish leadership into not spreading panic, in order to avoid an uprising. Vrbar later wrote: "That the negotiators and their families were in fact pathetic, albeit voluntary, hostages in the hands of Nazi power was an important part of these 'deals'."

It is alleged that Kastner who had received a copy of the Vrba-Wetzler report, failed to distribute it, and instead engaged in private negotiations for a trainload of 1,684 Hungarian Jews to escape to Switzerland.

When the report was completedThe Slovak Judenrat gave Vrba papers in the name of Rudolf Vrba, showing that he was a "pure Aryan" going back three generations, and supported him financially to the tune of 200 Slovak crowns per week, equivalent to an average worker's salary, and as Vrba wrote, "sufficient to sustain me in an illegal life in Bratislava."

He fought as a machine-gunner in a unit commanded by Milan Uher, and received the Czechoslovak Medal for Bravery, the Order of Slovak National Insurrection, and the Order of Meritorious Fighter. He legalized his new name after the liberation of Czechoslovakia. Vrba later emigrated Britain, where he worked at the Neuropsychiatric Research Unit at Carshalton, Surrey, and then for the Medical Research Council. He gave testimony at the Eichmann trial and also wrote a series of articles for the Daily Herald, which led to his vivid memoir, I Cannot Forgive, which was later translated into several languages.

Rudolf Vrba, who is survived by his second wife and a daughter, died on March 27, at the age of 81, one month before his book was due to be republished in Britain under the title I Escaped from Auschwitz.

Read the full text of the Vrba-Wetzler report [HERE]

Sources:

Vrba, Rudolf. I Escaped from Auschwitz, Barricade Books, 2002

Copyright: Anthony Skelton & Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T 2008

|