Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Other Camps

Key Nazi personalities in the Camp System The Labor & Extermination Camps

Auschwitz/Birkenau Jasenovac Klooga Majdanek Plaszow The Labor Camps

Trawniki

Concentration Camps

Transit Camps | |||

Majdanek Concentration Camp (a.k.a. Lublin KL) Reception, Prisoners Daily Life, Sub- Camps

Reception of Prisoners

Most prisoners were brought to Majdanek in freight trains in tightly closed, crowded cattle cars deprived of any sanitary facilities, without food and water.

The newly arrived were unloaded in the vicinity of the Lublin railway station, on a siding situated on the premises of the SS Fur and Clothing Works 1.5 kilometers from the camp.

The SS- men, shouting and cursing pushed and beat the prisoners descending from the train, then arranged them in fives, and marched the column to the camp at a rapid pace.

Surrounded by a dense cordon of SS-men and military police equipped with machine guns, as Zacheusz Pawlak recollects the arrival in Lublin of a transport from Radom on 8 January 1943 – “we had to march quickly. Some of the guards were holding dogs on leashes, the dogs barking furiously and baring their teeth at the prisoners. These were specially trained dogs. If a prisoner dropped out of the column even three steps, they immediately jumped at the victim. The SS-men and the military police terrorised the column by shouting and beating”.

Only the larger groups of prisoners deported from prisons, ghettos and camps arrived at Majdanek in trains. The smaller transports, usually from the Lublin district were brought in trucks.

As in every concentration camp, the newly arrived were subjected to the ritual of reception. After passing through the camp gate, the new arrivals were directed to barrack 44, where they had to surrender all they had with them and on them.

Naked – whatever the season of the year or weather conditions – they were rushed, with shouting and beatings to the nearby bathhouse, where all their body hair was removed, most frequently with dull razors, which caused acute pain.

From there they were taken to the neighbouring room to take a bath. They first underwent disinfection by submerging in concrete tubs filled with a Lysol solution. Next came the bath proper, which according to prisoners accounts, rarely occurred without various harassments. For example, hot water alternated with cold water, and so on. After such a “purification” , the prisoners were issued with rags, most often in the wrong size, to replace the clothes worn previously.

Division lll, which thenceforth took responsibility for the prisoner, directed them to the assigned compound and barrack. There followed registration, where numerous forms were filled in with personal details.

Next each new prisoner received a number and a triangle. The number replaced the prisoners name and the triangle indicated the cause of imprisonment. The numbering system applied in the Majdanek was different from those in other concentration camps, where the number increased as new prisoners arrived.

In Majdanek, the numeration went up to 20,000 and never exceeded that number. The newly arrived received the number of deceased prisoners. There were separate numeration systems, both up to 20,000, for men and for women.

The manner of identification was almost the same as in other concentration camps, Soviet Prisoners of War had the letters SU painted on the back of their jackets.

The number and triangle were worn by the prisoner on his clothes – the number, printed on a piece of white linen 14x 4.5cm, was placed on the left breast of the jacket or the dress and on the left trouser leg above the knee.

Besides, the prisoners received round badges, 3.8cm in diameter, with the number impressed on it, to be worn on a piece of wire around the neck.

Above the number, the prisoners wore the triangles printed on a square piece of linen, with a side of 8cm. In the middle of the triangle there was a letter indicating the prisoners nationality.

After fulfilling all the formalities, each new arrival had to undergo a quarantine, during which the functionaries taught them close order drill, forming ranks at the roll call, removing and putting on caps, marching in work-gangs, keeping order in the barracks,

Also those who, immediately after arriving in the camp had been accommodated in the compounds underwent quarantine. Still wearing their own clothes they were forced to learn close order drill, and only afterwards were they formally admitted into the camp.

This was the case, for example with transports arriving in January and February 1943 from Radom, Warsaw and Lvov.

Plunder of Property

Each new arrival was informed that they must place all their property for depositing, for possession of money or valuables was punished.

The looted property details was entered into a special register by the unit concerned with the management of property belonging to the prisoners in Division IV.

Clothing was recorded on personal forms titled Effecten-Verzeichnis, money on a money card – Geldkartet, and valuables on a separate form attached to the Effecten- Verzeichnis.

The depositing of the property was confirmed by the prisoner with their own signature. The property of prisoners of Jewish descent was entered into the register only after January 1943.

The prisoners employed in the Effektenkammer packed all these things into special sacks, attaching labels showing the prisoners numbers.

The sacks were stored in barracks number 43 and 44. When a prisoner was transferred to another camp, his or her sack followed them, the date of the transport and the name of the camp was entered into the register.

In the event of release, the property was returned and the prisoner had to annote as such in the appropriate spaces on the above mentioned cards.

When a prisoner died, the deposited property was turned over to his family. If the address was lacking, the belongings deposited became the property of the camp.

From 1943 onwards, the money, valuables and clothing left by prisoners who had died , Poles, Jews, Soviets passed into the possession of the SS Economic and Administrative Head Office.

The plunder was particularly ruthless as regards the property of Jewish prisoners. During previous incarceration in ghettos and camps they had been deluded with hopes of survival, so they tried to take with them whatever they still possessed, particularly money and valuables.

The Camp authorities attempted to seize these things right away. Since transports doomed to immediate extermination were not subjected to registration procedures, the SS were able to easily conceal the plunder.

Deceit was often resorted to, as in the case of the Jews from Czechoslovakia who had been promised good living conditions in the General- Government and were permitted to take with them money, securities, jewellery, and luggage up to 50kg per person. All the above were plundered by the camp authorities at Majdanek.

The new arrivals, seeing their property was being plundered, at times tried to conceal small valuable objects in shoe heels, or conceal them on their person. These measures were of little avail, since the SS men carefully searched all new arrival. While taking a bath, in the disinfection tube, prisoners were ordered to make appropriate movements, so the SS-men could discover hidden valuables.

Even if a prisoner managed to smuggle some valuables or money, the SS-men would often find it during searches of barracks or on the prisoners themselves returning to the camp from work.

The money or valuables found on prisoners was treated as “owner-less” and turned over to the treasury of Division IV, and this was the case with any money and valuables found on prisoners in the Majdanek sub-camps.

Until the end of 1943, Division IV shipped the property of Jewish prisoners to the storehouses of the Aktion Reinhard (SS- Standortverwaltung Lublin, Altachenverwaltungsstelle) located at 27 Chopin Street in Lublin, where all the valuables left by the Jews murdered in the death camps and ghettos were deposited.

The prisoner’s property was disposed of by the WVHA, which deposited money and valuables in a special account at the Reichs Bank, whereas other property was turned over to the Reichs Ministry of the Economy.

From the autumn of 1943, following the completion of Aktion Reinhard, the Majdanek camp administration sent all the plundered belongings direct to the WVHA.

Because of the lack of source materials it is impossible to estimate the dimension of plunder or to give any concrete total figures. All that can be offered is some illustrations:

From an analysis of 300 money cards of former Jewish prisoners that the average money deposited was 103 RM. The SS also looted clothing and other personal effects, as an example on the 20 July 1943 3900 women’s mantles, 2250 men’s overcoats, 700 coats and 1450 jackets were shipped from Majdanek to Chopin Street.

The receipts from 20 August the storehouse of Aktion Reinhard received 1800 women’s overcoats and 2900 dresses. Six days later, 3000 items of women’s clothing were received, followed by 103.80 square meters of fabric for men’s clothes, 73.20 square meters of fabric for women’s clothes and 70 headscarf’s on 28 August. These things were looted from the transports of Jews from the Warsaw and Bialystok ghettos.

Even the prisoner’s hair, cut upon their admission to the camp, was of value to the Third Reich, making socks for submarine crews, and for the railway staff.

Division IV established a commercial contract with Paul Reimann’s firm at Kostrze near Wroclaw, where it sent the hair collected from the prisoners. According to extant reports between 15 September 1942 and 26 June 1944, 730kg of human hair was gathered and shipped to this firm.

A considerable number of the Majdanek staff were involved in theft from the Reich and corruption. Property was misappropriated by the Camp Commandants Koch, and Florstedt – by the Chief of Division III, Hackmann – by SS non-coms Laurich, Gossberg – Kapos Kostial, Knott and others – by criminals acting as trustees, Peter Burzer, Theodor Hessel, Peter Wyderko, Julian Lang and many others.

Clothing

The complete set of clothes included – shirt, underpants, jacket, trousers and round cap without a visor. In the winter, the prisoner received additionally an overcoat without any lining of any sort.

The clothes were made of poor quality fabric with grey and blue stripes, so called pasiak. The women’s clothes were made of the same grey-blue fabric and consisted of a long sleeved dress and a white headscarf. In the winter, women were issued striped jackets and grey stockings. The set was complete with wooden shoes known as Dutch clogs or leather shoes with a wooden sole.

Beginning from 1942 such clothes were issued in Majdanek only to political and asocial prisoners. In 1942, striped clothes were given only to prisoners brought from other camps to assume functions in the so-called self-government of prisoners.

Soviet POW’s the first to have been brought to Majdanek, retained their military uniforms and hostages were allowed to wear their own clothes.

The Camps Inspectorate issued instructions on 26 February 1943, to camp commandants that prisoners employed within the bounds of the camp should wear appropriately marked civilian clothes.

In keeping with this instruction, prisoners were issued the most worn-out clothes of murdered Jews. On the backs of the jackets were painted in oil the large red letters KL separated by a broad stripe of the same colour. Similar stripes were painted on the trousers.

The children in Majdanek camp did not wear striped clothes. They could wear their own clothes or received civilian clothes left by adults.

The Prisoner’s Day

As soon as a prisoner had passed through the gate of their compound, they were immediately subjected to the full regime of the camp regulations.

Their day was filled from morning till the evening roll call with a maximum amount of activity – they were in constant haste, always fearful of beatings and vexations.

In the spring and summer period - from April till September, the reveille took place at 4am, and in the autumn and winter period at 5am.

Some barrack leaders, however, ordered the prisoners up earlier. Upon hearing the signal, the prisoners had to get dressed quickly, make the bunks, go to the latrine, drink the morning coffee, clean the barracks, and then the barrack leader would drive them out into the roll call yard amidst yelling and cursing.

Whatever the weather might be, the morning roll call commenced at 5am, in the summer and at 6am in the winter. In the roll call yard, the prisoners usually had to stand facing their own barrack. Perfect order had to be maintained while the number of prisoners was being reported. At the command: Stillgestanden, Mutzen ab, Augen links (Attention, caps off, eyes left), the whole column had to perform all movements correctly. “If only someone moved, budged, or turned his head, he would be beaten black and blue.”

In the initial period the sick and infirm were helped to stand up and still by their fellow inmates. Later they were laid on the ground, in mud and snow. Only from November 1943 they were allowed to stay in the barracks during the roll call.

The morning roll call for the whole compound lasted on average, half an hour, but only when the number of prisoners in the various barracks reported by the Blockfuhrers to the Rapportfuhrer talied with the figures supplied by the camps administration.

Otherwise, another roll call was ordered, which lengthened the time standing in the square by at least half an hour. At the command: Arbeitskommando formieren – the prisoners went running to form work gangs, hurried by the Kapos and the work overseers. After the work gangs had left, only the functionaries would stay in the compound – their task was to tidy the roll call yard.and supervise work gangs working the camps and the new arrivals who were still under quarantine.

At 11:45 am a lunch break was ordered. All the gangs working within the camp, or a short distance away would come running or marching very quickly back to their compounds. The returning prisoners were often searched by SS-men, in which task Schutzlagerfuhrer Thumann excelled.

There followed a check of the number of prisoners, so called Zellappell, in the roll call yard. If a prisoner was missing, a search would be instituted, which at times could last for several hours, during which the prisoners standing in the roll call yard would not be given anything to eat.

If however, everything was in order the prisoners received lunch, consisting of a ladleful of watery soup, this being frequently accompanied by harassment. After eating, or strictly speaking drinking the soup, the bowl had to be washed and placed in the barrack.

Around 1pm the gangs of prisoners would set out back to work, which in spring and summer lasted till 6pm, and in autumn and winter till 4:30pm

Fatigued, maltreated often running and dragging the dead behind them, the work gangs returned to their compounds for the evening roll call.

The evening roll call could last for two or three hours, and were especially long if a prisoner escaped, or fell asleep somewhere in the camp. Any prisoner found asleep were brought to the roll call yard for punishment. Until the autumn of 1943 such “escapees” were hanged on the gallows in the presence of the prisoners assembled at the roll call.

Another cause of the lengthening of the roll calls was the inflicting of punishment for transgressions of camp regulations. From the autumn of 1943 the roll calls were shortened considerably in order to exploit prisoner manpower more effectively.

The roll call was followed by supper and “leisure time” until lights out at 9pm, when silence was to prevail in the camp. The reality was entirely different, however, during the construction of the camp SS- men forced prisoners to do various additional jobs in “leisure time” such as tidying, levelling of the compounds, planting flower beds and planting trees.

If there were no additional tasks a prisoner could spend their leisure time talking with friends from other barracks, writing letters or washing. In some barracks in the men’s compounds functionaries organised drinking parties for themselves, during which they fought with one another, yelled, searched prisoners, maltreated them and even murdered them.

Housing Conditions

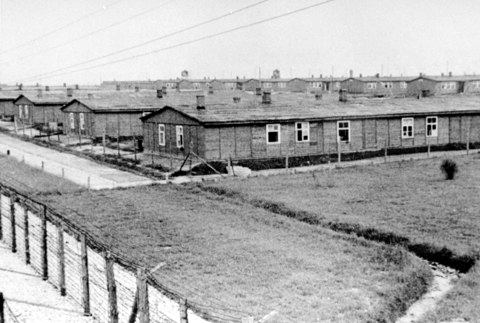

The Majdanek Concentration camp housing conditions consisted of primitive wooden barracks without elementary furnishings. The barracks were grossly overcrowded, with the constant influx of new prisoners, created inhuman living conditions.

In 1941 and 1942 the prisoners already imprisoned in the camp were waiting for new barracks to be assembled in order to ease the overcrowding in the existing barracks.

Prisoners arriving in early 1943 found the barracks in Compounds 3,4 and 5 erected but unfinished, without doors and windows and without any furnishings.

Prisoners accounts indicate a barrack housed on average 500 to 800 and even up to a thousand prisoners. According to the original plans of construction the barracks in Compounds 1, 2 and 5 were better constructed and were known by the prisoners as “dwelling barracks”, were supposed to house 550 prisoners each, whereas the stable barracks in Compounds 3 and 4 were supposed to accommodate 521 or 750 persons each.

The congestion in the barracks was at its worst during May to August 1943, when thousands of Jews from the Warsaw and Bialystok ghettos and Poles expelled from the Zamosc region were brought to the camp.

The number of prisoners living in the barracks in Compounds 3,4and 5 then exceeded a thousand in each, and for some Jewish groups there was no place at all, and they were lodged in the empty space between Compounds 4 and 5 where coal was heaped.

No prisoner could lay down freely on the floor for lack of space. They would lie down, at a command, on one side and also at a command, turn to the other side.

In the spring of 1943, partitions began to be put up in Compounds 1, 2 and 5 and after the barracks had been connected to a water main in the autumn of that year, the part at the head of the barracks was set aside for sanitary purposes.

Most barracks then comprised, a sleeping area and a small area for cleaning purposes. In addition there were in each barracks, tables, a closet for the prisoners files and some stools.

The barrack leader and the barrack clerk had separate bunks, separated from the rest by a special partition, whilst the other prisoners slept in 250 bunks. Each bunk was provided with a pallet and a bolster stuffed with straw or wood chips and with a blanket.

Throughout the history of the camp the individual compounds were allocated for various purposes:

Compound 1 – set up in late 1941 initially accommodated Soviet Prisoners of War and later civilian male prisoners. In the same year a hospital was established there, and in 1942 occupied the whole northern row of ten barracks.

The southern part was occupied by prisoners dwelling barracks and had a separate chancery. The hospital was moved to Compound 5 in September 1943, and the prisoners who were fit to work were transferred to Compounds 3 and 4.

In September 1943 the women prisoners were accommodated in Compound 1, in both the hospital and the barracks in the southern part.

In April 1944 healthy and sick women were transported to Auschwitz and Ravensbruck , Compound 1, was again occupied by men.

In May of that year, Jewish women brought from the forced labour camp at Budzyn were accommodated in three barracks, separated from the rest by a barbed wire fence. Between May and July 1944 this compound, one of two functioning, accommodated both men and women.

Compound 2 – from its establishment in the spring of 1942 until the winding up of the camp, was occupied by men. For the first year the inmates were from various nationalities, but after 1942 the camp was predominantly made up of Jews.

From the spring of 1943 right up to the liberation, this compound housed a hospital for former Soviet POW’s who had served in Wehrmacht auxiliary units and had been severely wounded.

Compound 3 - was occupied by men throughout the functioning of the camp. The first group of men were accommodated there in May 1942 when the northern row of barracks was almost ready.

These were hostages brought from the transit camp in Trawniki and other detention centres. Until the autumn of that year, the compound had housed almost exclusively persons detained for partisan activity.

During the summer of 1942, the barracks where hostages were living were surrounded by barbed wire. In spite of the sweltering heat, the prisoners were not allowed to leave the barracks.

Beginning from January 1943, Compound 3 began to be filled with political prisoners arriving from various prisons in the General Government.

During the year Jews from the Warsaw and Bialystok ghettos were incarcerated there, as were prisoners brought from other concentration camps and numerous transports of peasant families from the pacified villages of the Zamosc region.

In the autumn of 1943 and early 1944, transports of sick prisoners from Buchenwald, Dachau and Sachenhausen were housed there.

Following the evacuation of the prisoners to Auschwitz and Gross Rosen in April 1944 the compound remained empty until the liberation.

Compound 4 – like Compound 3 was occupied by men. From the autumn of 1942 until the camp was liberated hostages were accommodated there. Since, as is known, they were charges of the Ordnungspolizei, the compound was treated as a transit camp for that branch of the German police.

During 1943 and 1944 the compound also housed political prisoners brought from prisons and concentration camps as well as Soviet POW’s. In 1943, workshops of the Ostindustrie Company and the DAW were installed in some barracks there.

Compound 5 – the last to be occupied by prisoners was opened in October 1942. It accommodated women evicted from the Lublin districts of Wieniawa and Dziesiata and later Jewesses from the liquidated ghetto in Majdan Tatarski.

After a relatively short stay they were transferred to a Majdanek sub camp the SS- Bekleidungswerke at the former airfield. New transports of women arrived in Compound 5 in early January 1943, from Radom and somewhat later from Pawiak prison in Warsaw and the prison in Lvov. The arrival of these transports marked the beginning of the women’s concentration camp – Frauenkonzentrationslager – as a separate part of Majdanek.

During 1943, the compound was filled with transports of Byelorussian women and children, Jewesses mainly from the ghettos in Warsaw and Bialystok, women prisoners from the General Government and Ravensbruck and Auschwitz.

In the summer of 1943 the number of inmates in Compound 5 totalled between 6000 – 8000 women and children. When the first transports arrived in January 1943 the compound was still unfinished – it was completed during the first few months of that year.

During the same period thanks to the efforts of Stefania Perzanowska, a doctor from Radom, one barrack was set aside as a women’s hospital. From September 1943 due to rampant diseases another five barracks were allocated as hospitals.

After the women had been transferred to Compound 1, in September 1943 the 22 barracks were turned into hospitals for men. In July 1944 the compound was set up as a transit camp for persons forcibly employed by the Wehrmacht in the construction of fortifications around the town.

Food

Majdanek had its own farm and garden where fruit and vegetables were grown. To some degree Majdanek was self-sufficient as regards the feeding of the prisoners and SS- staff.

Food which were not produced by the Farm or the garden was received from the Food and Agriculture Department of the Office of the Head of the Lublin District.

The management of food provision was the concern of Abteilung Verpflegung in Division IV. Its chief task was to supply food products to the kitchens in the prisoner compounds and to the SS- mess hall. The prisoners ate their starvation rations three times a day, always in front of their barracks, except in winter, whatever the weather conditions.

For breakfast, a prisoner received about half a litre of black ersatz coffee without sugar, or tea brewed from weeds. Once or twice a week coffee or tea was replaced with a soup surrogate, water with wholemeal added.

Lunch which came at 12 o’clock consisted of three quarters of a litre of soup made of turnip, rotten potatoes, kale, dried cabbage leaves, and from the spring of 1942 of weeds growing wild within the camp.

It was only in the autumn of 1943 that soups prepared from weeds were stopped from being served. The prisoners then began to receive soups made from turnip, potatoes, beet pulp, carrot, and sometimes cabbage or barley soup. These soups were thicker and small amounts of fat, meat or horse sausage were added.

Supper, the basic meal, was served after evening roll call. It consisted mostly of coffee or another brew and 5-7 ounces of bread. At times the brew was replaced by soup, and a few un-peeled potatoes.

On occasions the prisoners received as an addition to the bread, a slice of horse sausage, a spoonful of marmalade, margarine, or cheese.

The prisoners daily diet contained less than a 1000 calories, well below the norm for people undertaking hard labour. Due to the poor food rations both in terms of quality and quantity, a very large number of prisoners were doomed to die, within a short space of time.

On these rations after a short time the skin became grey-blue, grew thinner, became parchment-like, hardened then peeled off. Hair became coarse, and the head took on an elongated form, with the cheek- bones and eye-sockets becoming more prominent.

In Majdanek these prisoners were called gamle, which in the German Silesian dialect means idiots, in Auschwitz emaciated prisoners like those described above were called Moslems

In the last phase of starvation, prisoners no longer felt hungry, refused to accept any food, were unable to emit any sound. Self-preservation vanished – they were past any help.

They perished under the blows of the Kapos sticks, or the SS-men’s rifle butts, they died in barracks, in the fields, in the hospitals, in the so-called Gammelblocke, where those still giving any sign of life were taken to the gas chambers.

Punishments and Executions

In the Majdanek concentration camp whipping by SS-men or trusties was the most frequently applied punishment. Prisoners were whipped until they lost consciousness for minor offences. Whipping was inflicted on both healthy, sick and even dying prisoners – a prisoner was often whipped because he was Jewish or a Gypsy.

Aside from the informal whippings, there took place official punishments where floggings were carried out on the basis of reports for an offence.

These offences could be committed by individual prisoners or groups, and reports were submitted by SS-men or functionaries to the camps authorities – Division III.

The punishment was inflicted after the evening roll call. The flogging was administered on a special table officially known as the Block, but called by the prisoners “the grand piano”. The top of the table was made of thick boards, was semi-circular. The prisoner to be whipped put his or her feet behind a special board at the rear of the table and laid down on their stomachs, while two SS-men or Kapos held their arms twisted back in between the shoulder blades.

Two other SS-men or Kapos then beat them with whips or sticks. The number of strokes varied from 10 to 200 and more. The “offender” had to count the strokes in German, which to many was a considerable problem, and this caused additional strokes.

The consequences of this type of punishment were always dangerous – it resulted not only in cut skin, but frequently caused internal injuries to the kidneys etc.

From the autumn of 1943 the floggings were curtailed lest it should render the prisoner unable to work. The cruellest of the SS-men included the Commandant of Compound 3, SS- Unterscharfuhrer Groffman, who during the roll call, walked up and down the compound searching for victims.

He positioned a prisoner slightly aslant, aimed his hand at the place he intended to strike, and next with a single blow at the stomach, the liver, the heart or the ear knocked the prisoner down.

Another sadist SS-man Gossberg, smashed heads whilst SS – Unterscharfuhrer Franz Josef Fritsche killed prisoners with a spade, a rifle butt or whatever was at hand.

The greatest murderer in Majdanek’s history was Anton Thurmann, who was brutal and sometimes personally whipped prisoners – giving them 300-400 lashes.

Prisoners were also immersed in fire tanks and cesspools, and the “pillar” was also used where a prisoners wrists were tied behind him, and being raised on a post to such a height that his feet did not touch the ground.

The death penalty was inflicted for more serious offences. Jews attempting to escape who were recaptured were as a rule hanged on the gallows.

Executions by hanging were carried out during the evening roll call in the presence of the camp commandant, the head of Division III , a physician, and the SS staff of a given compound.

In Compound 3, the hangings were performed by the Kapos Karl Galka, and Peter Wyderko. In the women’s compounds the executions were carried out by the crematorium chief Erich Muhsfeldt.

Working

The gangs that built the camp remained at the disposal of the Construction Board. Between 1941 and 1944 an estimated 70 working gangs were employed at various construction tasks, such as earthworks, building and outfitting work.

Earthwork accounted for the bulk of the jobs performed – it included levelling the ground, extraction of sand and stone, building roads, embankments, pillar-boxes, drainage ditches, wells and drillings of water mains and sewage

All these jobs were performed by a large number of gangs, at least fifteen were employed from mid-1942 to mid-1943 and 1,000 to 2,000 prisoners were employed.

Building work encompassed the construction of barracks, watch towers and fences, facilities for mass extermination. The most numerous among these groups were the gangs building the individual compounds, cellars for potatoes, laundries, administrative buildings and fences.

During the period from the autumn of 1941 to the end of 1942 about 1,000 prisoners were engaged in these tasks. A much smaller number of prisoners not more than 500, were employed by the Construction Board, at outfitting work. This work required skilled labourers such as electricians, glaziers, plumbers etc.

Clerical staff were employed at the Camp Command, the Political Division, Division III , the Post Office, the Employment Office , in various sections of Division IV. The prisoners working in these units were mostly educated people with a good command of German and clerical skills.

About 20 gangs were constantly engaged in cleaning work – their task was to keep clean the SS and prisoners living premises.

The cleaning of the prisoners compounds and the removal of snow in the winter was the concern of the Feldkolonne. In 1942 and 1943, there were teams of 15-20 prisoners in each compound who removed the faeces from cesspools to the camp gardens. As a rule Jews were employed to perform this exceptionally dirty and hard work.

Its only advantage was that, because of the stench from the barrels and prisoners clothes, the SS-men and functionaries usually left the group alone, thus the Scheisskommando – as it was commonly called avoided beatings.

In the years 1942 –44 other work gangs were engaged in removing garbage from the Camp Command, the guards quarters and the camp farms, in cleaning the kennels, stables and so on.

In 1943 upon the completion of a number of camp buildings and facilities, permanent work gangs were set up to carry out regular maintenance and improving the appearance of the camp, such as planting shrubs, and flower –beds.

A number of work gangs were employed in various workshops and storehouses – about 60 –100 prisoners worked in the carpenters shop, manufacturing furniture for the camp staff, repairing furniture and making alterations in the barracks.

The blacksmith and locksmith workshops rendered services to the Construction Board for the barracks and sewage and water mains construction.

Those employed in the electric workshop repaired electrical wiring, as well as loudspeakers, radio sets and electric stoves brought in by SS-men.

Early in 1943 the camp authorities established a car repair shop, in which a gang of 20 prisoners engaged in switching petrol and diesel oil powered vehicles into natural gas powered ones and in replacing worn out parts. Another gang cleaned vehicles in the garages.

An exceptionally large number of prisoners were employed in the tailors workshops, 270 persons. Initially only men worked there, but from 1943 women were employed, and they soon became the majority.

The sewing room repaired chiefly confiscated clothes as well as prisoners linen and striped clothes. A group of women knitted earlaps, socks and gloves for the German army. A gang of men sewed and repaired uniforms for SS-men.

Over a hundred persons were employed in the shoemaker’s shop, repairing prisoners and soldiers shoes and sorting out and repairing footwear to be taken to the Reich.

In the camp storehouses, both men and women prisoners were employed in the Effekenkammer, they received and stored prisoners belongings. They searched the clothes of murdered Jews for money and valuables and sorted out and prepared the clothes for shipment.

The farm gangs worked from the early spring till the late autumn. They engaged in ploughing, sowing, weeding, grass mowing, grain harvesting, root plant lifting, threshing or growing potatoes and vegetables.

About 1500 prisoners were employed on the farms – they worked very hard in the open air regardless of weather, under the brutal supervision of functionaries and SS-men.

The work gangs whose task was to supply prisoners and SS-men with food was organised on a permanent basis. Some of them delivered potatoes and vegetables to the kitchens in the prisoner compounds, others prepared meals. The carrying of cauldrons with food to the barracks was the job of room seniors.

About 15 work gangs carried out sanitation and special tasks – including working in the bathroom and barber’s shop for new arrivals and those already staying in the camp.

The Sonderkommando in view of the character of its work, was tightly isolated from the others. Their job was to remove bodies from the gas chambers and burn them on pyres or in the crematorium ovens.

The part of the Sonderkommando which burnt dead bodies in the Krepiecki Forest seven kilometers away from Majdanek in 1942 –43 was called the Waldkommando.

The fate of the Sonderkommando members was foredoomed – now and again they were executed as being unwanted witnesses to the greatest crimes.

The SS institutions had priority in utilising prisoner manpower – particularly by the Deutsche Ausrustungswerke (DAW) and Ostindustrie.

The DAW had existed in Lublin 1941 and employed the prisoners confined in the labour camp at Lipowa Street. As the work expanded, some of the prisoners were transferred to a separate labour camp in Chelmska street and some to Pulawy.

In 1943, a total of 5500 prisoners worked in these three factories. In 1942 the DAW opened in Majdanek a ski-repair shop employing 60 people, and the next year a shoemaker’s shop employing over 200 prisoners.

The Ostindustrie opened four workshops in Lublin. They included a brush making and basketry workshop, a brick kiln, a metal works and a pharmaceutical factory.

All of them employed prisoners from Majdanek, some 2000 in 1943, almost exclusively Jews. The first of these workshops was located in a former airfield in the vicinity of the camp produced munitions baskets and brushes also in the camp itself.

Altogether close to 1,500 men and women prisoners were employed in the manufacture of baskets and brushes. The metal works which dismantled weapons, repaired metal equipment and dissembling gun carriages, employed 240 prisoners, while the small pharmaceutical factory directed by the SS garrison physician from Lublin, Dr Sekel, was staffed by 35 Majdanek prisoners, Jewish physicians and pharmacists from Holland.

The SS Fur and Clothing Works – SS- Bekleidungswerke, a branch of the Majdanek camp from the autumn of 1942, operated its own labour camp. Before the opening of the camp 1200 prisoners were brought from the main camp each day to work on the building site and at sorting out the clothes collected.

The SS and Police Central Construction Board in Lublin used Majdanek prisoner labour during the construction of a supply base for SS units in the occupied Soviet territories.

During the years 1942 –43 prisoners were employed on the building site of a Supply Storehouse of the HSSPF Southern Russia and the Caucasus, in which various military equipment and food were to be stored, a Motor Vehicle Supply Post of the Ordnungsdienst in the East, and in 1944 they built a Motor Vehicle Park for the Eastern Territories.

In addition to working in SS enterprises, Majdanek prisoners were employed by the Lublin Zentralbauleitung at the construction of a Sewage Gas Plant, and on the building site of a huge stadium for the Majdanek SS-men. A total of about 600 prisoners were employed there.

Prisoners of the Majdanek camp were also hired by civilian institutions and organisations in Lublin, such as the Central Agricultural Office which employed about 130 persons, the Tobacco works and the town laundry, power station and railways.

Various building firms availed themselves of the cheap prisoner labour. The number of prisoners employed altered frequently, depending on the jobs to be done. The average employment for one building enterprise amounted to 45 prisoners.

According to the price list fixed by the WVHA, civilian firms paid four marks per skilled worker per day and three marks for an unskilled worker. Until the 1 June 1943 SS enterprises paid only 30 pfennigs per work day, regardless of a prisoners skills – from that day onwards, the rates were equal for both SS an other enterprises.

Sources: Majdanek – The Concentration Camp in Lublin by Josef Marszalek – Interpress Warsaw 1986 Holocaust Historical Society National Archives Kew Copyright: Rowland Hille, Heart 2007-02-07

Copyright SJ H.E.A.R.T 2007

|