Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Other Camps

Key Nazi personalities in the Camp System The Labor & Extermination Camps

Auschwitz/Birkenau Jasenovac Klooga Majdanek Plaszow The Labor Camps

Trawniki

Concentration Camps

Transit Camps | |||||||||||||

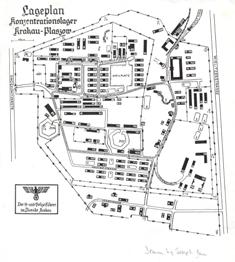

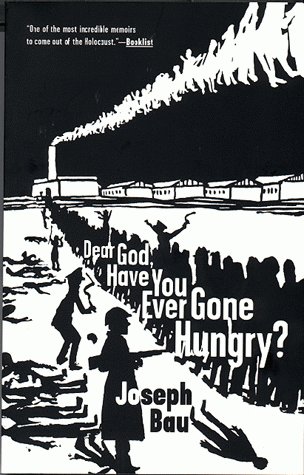

Plaszow Concentration Camp Joseph Bau’s – Journey Through the Past

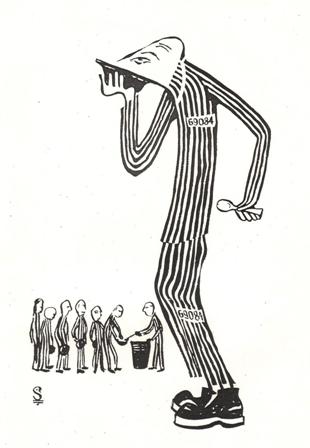

Former Plaszow inmate Joseph Bau (Prisoner Number 69084) invites the reader to a virtual tour of Plaszow Concentration Camp, as it was in 1944.

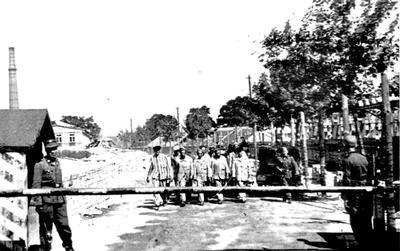

Here is the Main Gate – thousands of people pass through it – in rows of three, keeping time to the monotonous pace of the rasping bellows of the Kapo, “Links, Links, Links” to the accompaniment of the hollow echoing of wooden shoes. The road -block loomed above the shaven heads of these innocents, whose only crime was imprinted on their identity cards – that they bore the title “Jude.”

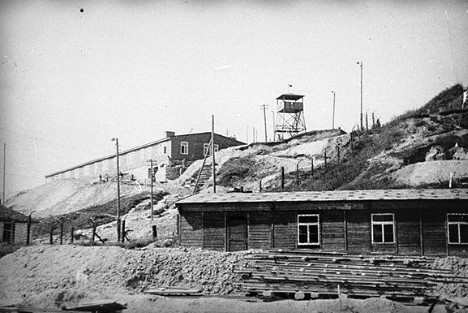

In those days, in those glamorous days of the death camps, a very apt slogan was born – “You enter here, through the main gate – You exit through the chimney.” On two sides of the main gate, on the left and on the right, running to a height of three metres, is the electrified fence, the length of which is four kilometres.

The fence surrounds the entire camp. It comprises two barbed wire lines of walls. Between the barbed-wire of the inner wall are strung high-tension wires, on porcelain insulators. Along the outer rim of the entire length of this wall of death, the area is surrounded by a complex arrangement of barbed-wire of five metres depth.

Above this fortified wall are perched 13 watchtowers. Each watch tower was equipped with a machine gun, phone unit and with a revolving searchlight set upon its roof. Day and night these towers were manned by SS guards, and in between the two lines of wall, the dogs were unleashed, trained to attack people clad in striped prisoner garb.

This quilt of fortifications and obstacles, set up to prevent any possibility of escape from the killers net, was constructed by the imprisoned ones themselves, under the tutelage of the German “experts” and according to the inspired plans with their demonstrated efficiency in the erection of camps.

We have passed the gate. Today there is no SS guard, menacing gun at the ready to count us. Nobody searches our pockets for bread or sugar, nor does our Kapo inform us in his animal –like bellow “Zwei und Zwanzig Haeftlinge von der Bauleitung” (twenty-two prisoners from the building detail) and look here, we have already arrived in the area that once was in the sole possession of the “angel of death” and his trusted helpers, the Waffen –SS and Polizei Fuhrer.

To this place, even the sun would have not dared to seek access. Those in the know were convinced that she (the sun) would not have received a “Passier erlaubnis” (permission to enter) from the authorities in charge. Today the laws of the jungle no longer apply. We are walking, unbound, but in respectful silence as be-fits this sacred place. Beneath our shoes tiny pebbles rustle…. pay attention to these stones, please listen, they are weeping, and when you lift one such stone, you will feel the texture of marble.

If you should squeeze one between your fingers, you would see that it is no ordinary stone – there are Hebraic inscriptions engraved on its surface. Yes, all the roads in Plaszow camp are paved with tombstones of desecrated graves. A special detachment of the imprisoned ground the magnificent tombstones into pebbles and gravel and a second group of imprisoned pressed the pieces into the earth of the cemetery, with the aid of sledge-hammers and hand rollers.

Presently, we are passing by two very notable structures. On the left, a two storey building (155) built before the war, which houses the headquarters of the duty officer, the telephone communications centre and the radio room, which is connected to a system of loudspeakers that reach the entire camp.

During an “Aktion,” dance tunes and lively music were broadcast from here. On May 14th (one of several fateful dates) for example, providing a musical background for the sick and the young children who were being sent to the ovens of Auschwitz from here, the radio technicians with their sense of humour, could be heard singing the German lullaby “Goodnight Mammy.”

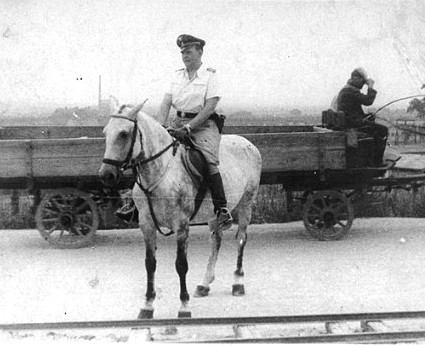

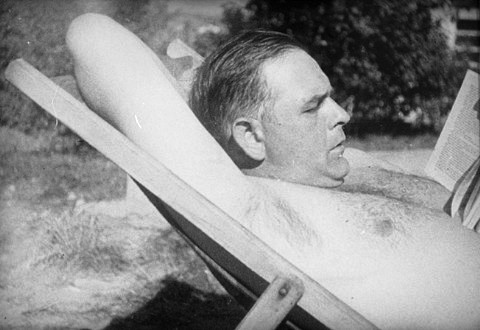

On the other side of the road stood the hut of the officer in charge of the camp, the “Kommandantur” (201). Here was the the headquarters of “Kommandant” Amon Goeth – a hideous and terrible monster who weighed more than a hundred and fifty kilos and who reached a height of more than two metres.

His infamy preceded him, set the fear of death in people, terrified the masses and accounted for much chattering of teeth. He ran the camp through extremes of cruelty that are beyond comprehension of a compassionate mind.

Employing tortures which surpassed anything designed by the inquisition, he would dispatch his victims to hell, for even the slightest infraction of the rules, he would rain blow after blow upon the face of the hapless offender, and would observe with satisfaction born of sadism, how the cheek of his victim would swell and turn blue – how the teeth would fall out and the eyes would tear.

Anyone who was being whipped by him was forced to count in a loud voice each stroke of the whip and if he made a mistake, was forced to start counting over again. During “interrogations” which were conducted in his office, he would set the dog on the “accused” who was strung by his legs from a specially placed hook in the ceiling.

In the event of escape from the camp, he would order the entire group from which the escapee had come, to form a row, would give the order to count to ten, and would, himself, kill each tenth person. At one morning parade, in the presence of all the imprisoned, he shot a Jew, because, as he complained, the man was “too tall” – then as the man lay dying, he urinated on him.

Afterward, he shouted to a friend of the dead man: “What, this doesn’t please you?” and shot him too and urinated on him as well.

T here was one case of a man who, in hunger, had stolen a potato from the store room. On the orders of the camp commander the “suspect” was hung near the gate of the residential quarters, with a potato stuck between his teeth and a sign attached to his collar which read – “I am a potato thief.” Once he caught a young boy who was sick with diarrhoea and who was unable to restrain himself, and forced him to eat all of his excrement.

A fter a meal of raw meat mixed with fresh blood for him or his dogs, the “Kommandant” would tour the barracks, having with him, two bull-dogs trained to attack people. After his “visit” the results of the “harvest” would be tallied:

“Twenty to nothing, Fifteen – Nothing, Thirty – Nothing.” This “nothing” was, however, always on our side. It might have been possible to kill the monster “Kommandant,” but then the scorecard might have read “Twenty-four thousand” (them) to “One” (us).

In the “Komandantur” hut, there also was located the Bau-Leitung (the building administration). There in the Bau-Leitung, Jewish engineers worked according to the crazy instructions and the frenzied pace laid out by the “Kommandant” and were successful in meeting totally unrealistic completion schedules in the execution of projects which no engineer in his right man would concede were possible to accomplish.

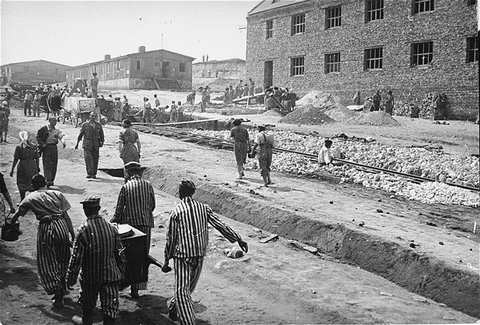

Groups of “Barracken – Bau” (brarracks builders) laboured, sometimes without relief, day and night, at double time, under work norms which were first doubled, then quadrupled , in order to complete the “hot order” by its scheduled date.

Responsible for putting all the rantings of the “Kommandant” into effect was the engineer Grunberg, and he was paid “in full” for any shortcomings in the projects, or for any delay in their execution. Engineer Grunberg knew that the “Kommandant” would not kill him and so took upon himself any mistakes. Without a word he would absorb the blows that would have sent a heavyweight boxing champion to the canvas.

After those terrible punishments, Grunberg the engineer no longer looked like a member of the human race – but despite everything, he was forced to continue his work, without medical attention or even first aid.

Above the “kommandantur” hut of my Plaszow there burns an eternal lamp, next to a memorial plaque which reads:

“Dedicated to the sacred memory of Sigmunt Grunberg, who sacrificed himself to save others.” We the grateful imprisoned of Plaszow will not forget you.

I too worked for a certain period in the Bau-Leitung, as a draughtsman, I was responsible for charting a map of the camp. I too, more than on one occasion got “twenty across the arse” according to the official rules and several times, was saved only by a miracle from certain death.

Before us, “Leichen – Halle (164) the remains of an elegant building built in the eastern style, that had served as a funeral hall before the war. The Germans converted the building into a horse stable. Over a period of time, as the number of horses, confiscated from the Jews, increased to over one hundred, the stables were moved to a special camp and the building was demolished with explosives.

For some strange reason the demolition was not completed, perhaps they left these fractured walls as a statue and as a sign to commemorate the devastated Jewry of Poland. The road turns to the left.

We are now passing by “Wach- Kaserne (163) a single –storey building of a military installation built in the shape of a quadrangle. Surrounding the broad yard, stand the huts, which contain the rooms of the Ukrainian militia, a kitchen dining hall, canteen, work-shops for tailors, Jewish shoe-makers and an arsenal.

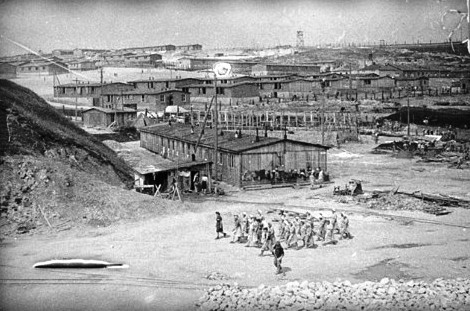

Because of the gloomy atmosphere, the gate leading into the yard has been decorated with a tower of the type found in the Middle-Ages. Constructing the military barracks was most difficult. It was winter. Fierce and icy winds were blowing, snow and sleet fell like rain, and the building was constructed on the down-slope of a hill, in muddy drenched earth.

Scores of people fell victim to the construction of this lofty edifice, in which all the imprisoned of the camp had been involved. With the exception of a group of builders, carpenters, plumbers and tinsmiths, who worked day and night without holidays, the remainder of the people who were involved in another work project – transported the work materials.

After the morning roll-call, and before the evening roll, everyone took part in this parade, carrying on their shoulders planks, pipes, stones and bricks. And wouldn’t you know it, when one part of the building was already standing, a barrow filled with bricks suddenly pushed against and knocked down one of the columns and the whole building collapsed like a deck of cards.

The SS man Hujar, who was in charge of the building project, blamed the failure on the work engineer, Diana Reiter, and began to beat her. She was a small frail woman, and after the initial blows, she fainted…. but the SS man continued to hack at her.

He struck her body, which was falling to pieces, with a wild passion. I heard only the sound of the whip and saw only a red face covered in sweat and grime, rising and falling. Finally, the SS man Hujar, fired off an extra volley of bullets into the pile of bones, rags and blood as if he wanted to be quite certain that the lady-engineer would never get up again.

And now, here is the “Das Graue Haus” (the grey house) – (171). This structure was built before the war and when it became part of the camp, some very famous SS gentlemen lived there; Hujar, Zdrojewski, Landesdorfer, Eckert and Glazer.

In the basement was a prison cell – and not just any prison, but the real thing, a real chamber of horrors. There was a very narrow jail made of iron, just big enough to stand in, not unlike a wall closet that has been hermetically sealed.

There was also a narrow cell for lying in, into which it was only possible to gain access by shoving a person inside head-first. There was a special whipping bench, chains for hanging, ivory handled whips made of dried cow’s hide.

In addition to these particular auxiliary aides there were, of course, isolation cells, dark and wet with a small opening in the door through which water could be passed. In most cases, anyone who merited the professional ministrations of this particular institution did not emerge from there under his own steam – he was dragged out by his legs straight to the communal grave where others who had shared the same fate, awaited him: others, who had also been dispatched on the very same day

We have come to an intersection. Before us SS – street, which leads us to the “Neu Gelende” (new territories). Across its entire length stand the villas of the officers (117, 179, 181, 183), and the red villa (178) “Rotes Haus” that belonged to Kommandant Goeth.

We turn right onto “Berg Strasse,” in the direction of the entrance to the residential barracks. On the left, at the foot of the hill, the “Stein-Bruch” (the quarry) stretches forth. The quarries were a symbol of the concentration camps and an inseparable part of them. Plaszow quarry, however, was somewhat different from the others. Here women hauled rocks from the crushed boulders in freight cars, out to the “Neu Gelende” to the point at which the SS road began.

The railway, which they called, “Manschaftzug,” comprised the railway cars (in each car two tons of stones) and was hitched up to 70 women, in two rows. Emaciated women, pale and hungry, dressed in sacks and rags, did the work of a train’s locomotive. The labour went on for 12 hours, from six in the evening till six in the morning, without any attention being paid to the darkness of the night, the cold, the mud, the downpour of rain storms, ice or snow.

During a single shift, the work norm for these women meant traversing the entire circuit 15 times. The boulders were broken down in the quarry by members of the “Straf-kommando” (punishment detail). Those people wore a red circle printed on their backs were sent to the “Straf-kommando” where they did the most arduous labour.

Their Kapo was a German racist who, from top to bottom, oozed pure German blood. The sign of the “green triangle” he wore bound across his chest with great pride, emphasised his superior pedigree – “Berufs- Verbrecher” (professional criminal).

It was a source of great pleasure to him to kill people. When he was not provided an opportunity to inflict death upon others, for lack of choice he would murder some Jews. He would boast that he had belonged to the famous Dillinger gang in America, and had, as a token of special recognition to his outstanding career, earned a life sentence in jail.

He loved to knock his victims to the ground, put a stick at their throats and stand on both ends of the stick, or at times, on the man’s neck. Another of his specialities was to order someone from his group to carry upon his back a large, heavy rock and run around in a circle with it, while he stood in the centre, like in a circus, beating upon the poor creature with his whip until the man fell, squeezed beneath the rock.

He had, as the Kapo of “Stein- Bruch,” many other methods of causing death – many that he invented himself and only unto himself did he permit the right of putting these into practice. The hut which stands next to the quarry is the “Hur Haus” (brothel) – (173). It serviced the SS. Because of “Rassen Schande” (Race Shame), Jewesses were not “employed” there.

The second hut (172), situated close to the road, was designated for the officers of the “Verwaltung” (administration). Here, the central index of all prisoners was located. Here Jewish clerks made ready lists of the sick, the old, the children and those who had refused to work: all those selected for burning.

Here also they would compile lists of food and supplies needed in the camp kitchen. In the “Verwaltung” were stashed away all the reports of the “parades” in the “Appell Platz” and all the “Baracken Regulierung” (barrack regulations) were posted there.

Here was situated the “Lagerfuhrer” (officer in charge of the residential barracks) and here in the yard, the hanging tree was at the ready. One winter the “Bau-Leiter” got into an argument with the “Largerfuhrer” and wanted to make him mad…. in this instance it was me who served the role of principle victim.

At the time I was working with the camp electricians. One day I was summoned to the “Bau-Leitung” to make a sketch of the new camp. That evening the “Bau-Leiter” instructed me to remain in the office with the engineers.

He said that everything had been taken care of and I was free to miss the evening roll call, but it turned out to be a very funny trick indeed, that he had played. The “Bau-Leiter” had made no such call to the “Verwaltung” and did not notify the Kapo of the electricians that I was with him.

When, later that night, we were returning home, Grunberg, the engineer, announced to the “Lagerfuhrer” who was standing at the gate, “Zwei und Zwanzig Haeftlinge von Bauleitung und ein Elekritker” (twenty two prisoners from building administration and one electrician) …. it turned out that I had been reported missing during roll call at the “Appell Platz”

They had searched for me all over the camp for several hours. I was responsible for the fact that all prisoners had been forced to stand in the snow instead of going in to eat and rest after their hard work – at least, this is how the “Lagerfuhrer” explained it to me, as he beat me about the head with his whip.

After scores of blows to my skull, I thanked him in the most pleasant possible manner. I asked his forgiveness and promised him that I would never again cause him such problems. Like a drunk, barely conscious, I joined the group of engineers returning to the camp. The next day, I heard the “Bau-Leiter” telling a group of SS men how he had screwed the “Lagerfuhrer.”

We are past the second gate and we are now completely enclosed in a camp within a camp. The residential camp is again sub-divided into a number of fenced and re-fenced camps: the men’s camp, the women’s camp, a camp for Poles – and inside the smaller, that is the residential camp which is inside the large camp, there were further smaller camps, enclosed by barbed wire.

Each mini-camp like this, then, had its own gate and guard. Whenever someone with some duty to perform had to pass through these gates of hell – whether departing or returning, he would come to a halt in front of the guard and, standing at attention, would remove his cap and, in a loud voice and in a tone suited to the eminence he was addressing, would request permission thus:

“Prisoner 69084, has a duty to perform …. to ….. and requests permission to enter or to leave.”

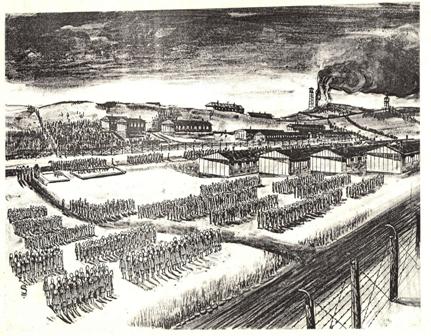

In every hut there was a “Baracken- Altester” (barracks supervisor) and in each mini-camp there was a Kapo and from each of these worthy notables, permission had to be sought in turn. Gentlemen, over on the right you see the “Appell Platz” (the parade ground). A broad expanse of which, twice daily 24,000 people assembled. According to the number of residents and going by the rules of the normal world, Plaszow camp should have enjoyed the status of a medium sized city.

At certain times we would all stand sometimes for an entire day, sometimes through the night and a few times, day and night, without a pause, on our feet constantly, in silence, without food and without the right to go the “Latrines.”

God help anyone who moved out of line or said something or sat on the ground. People would sleep while standing, would wet their pants and right up to the last moment were unaware of what waited them. Twenty-four thousand Jews stood, from morning till night, in dumb silence and it was possible to hear a fly buzzing in the air.

On a regular day of merely mundane tortures, at six in the morning, at Appell time we would stand according to our assigned places of work. A Kapo arranged us in rows of threes and reported to the SS man on duty. Number of healthy prisoners capable of working. Number of sick who had received “Schonung” (permission to stay in barracks)

Number of deaths, that had occurred during the night, and whose bodies had been transferred to the “Himmel Kommando” (the heaven squad). On the other side of the “Appell Platz” stood those who had completed the night shift, and who were arranged according to their barracks. Over these the “Baracken – Altester” presided and he would provide a detailed report to the SS man on duty. Number of people who returned alive from the work detail. Number of dead returned on stretchers

At six in the evening, the process was inverted. The reports were checked by the SS men, according to the general number of prisoners. In the event of a mistake or inaccuracy in the accounting, we would all remain standing until the unfortunate who had fallen asleep in his bunk or had joined the wrong group or who had been “sent some place” and had failed to notify of such was found.

Between Berg-Strasse and the Appell- Platz, there are two pools full of dirty water and covered with algae, in the same condition now as they were then. After a number of fires broke out in the camp, the “Kommandant” had ordered that the small huts that were built too close together (five metres apart) be demolished and from these materials longer huts be built: less comfortable they might be, but at the required distance of 15 meters from one another.

To prevent fires, they organised a group of fire-fighters, and dug 15 pools that were never used, but which provided a perfect spot for mosquitoes to breed. Every single one of the imprisoned had lice, bugs and his own personal collection of fleas. The flies and mosquitoes were just one more unbearable suffering inflicted on everyone.

Now we are turning onto the street that passes between the two rows of men’s barracks. The entrance to the hut is in the middle of the Northern wall. A long corridor divides the hut into two parts. In each section, two halls: in each hall, two rows of bunks from floor to ceiling. In the corner, next to the door, cooking utensils and a large pail of water. In the middle of the hallway, a small stove for heat in the winter. No where will you see a closet, not even a simple trunk, because for the people who live in this hut, apart from the lice, there was absolutely no private property.

Sometimes problems arose over who had title to a nail which was stuck in the bunk post, who had the right to hang some rag there, while it was taking up room that rightfully belonged to a towel, or to some wet rag-cloth. All those articles were the property of the SS Polizeifuhrer, such as a dish and a spoon, wooden shoes, caps and side bags were rolled up into a single bundle in the striped jacket, which served as a pillow under one’s head in such a manner, one was able to protect one’s “riches” from being stolen.

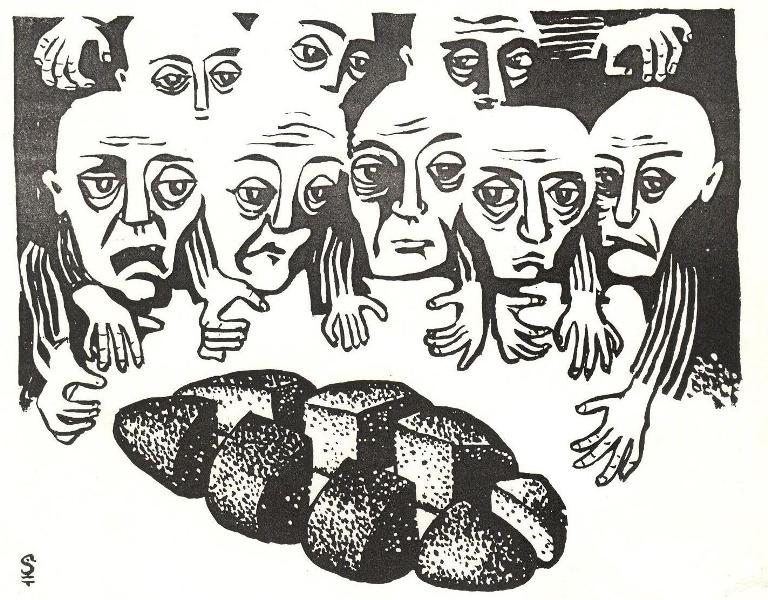

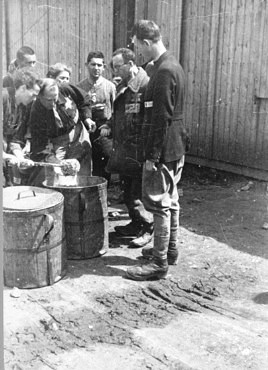

Sometimes in the night, someone who knew how to restrain himself, would add a half-slice of bread to his dirty and stinking little bundle, for breakfast. Each evening the “Baracken- Altester” would distribute the food ration, a loaf of bread (1 kilogram) for four people and a cube of margarine for 12 people. In the morning, we received a quarter of litre of tepid, black water which we called coffee.

We have arrived at the street that separates the men’s and women’s camp. As usual the barbed wire signifies a boundary between the two camps. Across from us, a side entrance to the “Frauen Lager” and the entrance to the “Ordnungsdienst” – civic order service, or more simply put – The Jewish Police.

Before we visit here, we’ll go and take a look at some other historic sites of importance, rendered holy by the blood of our brothers. Over here, Quarantine Camp, two huts (15, 16) and a Latrine (17) surrounded by barbed wire. This is where the new Jewish cemetery of Krakow used to be. After the destruction of the ghetto, after the “Action,” the final one, the Germans brought to this place, all those who had hidden themselves in their homes and had not shown up for the transport (13.3.1943).

At this spot, a deep pit had already been prepared in the ground, and inside it, they killed more than 2,000 people. In order to cover the bodies with earth, they brought up people from nearby huts. By the time my group arrived, the work was already close to completion. The surrounding tombstones were already sanctified with blood of the martyrs and were covered with layers of spattered brain-matter.

From out of the soft earth protrude arms and legs, I saw a woman’s hand moving, and a finger beckoning, it reaches slowly upward, inch by inch, just like an own, as if it were pleading and warning that the day of revenge was still to come. To this common grave, the Germans added more of their victims from smaller “Aktionen.” When the pit was full, they moved the killing ground to some old trenches from World War One and over the mass grave, they ordered that a “Latrine” be built (17).

Next to the Quarantine, or that section of the hill which had been levelled and paved, stands the Wash House (49) the Clothes Storage (48) and the Delousing Centre (50). In preparing the spot for building they had used the “Bagger.” All the earth taken out of the slope by the tractor was thrown onto the steep descent at the other end of the field.

The tractor would remove the earth from the cemetery, alive with rotting bodies, covered with infesting maggots, dispersing the “sleepers” who were even then not entitled to their final rest. The tractor driver was called “The Dentist” because he would remove the gold fillings from any skulls which fell from the earth mounds with a hammer.

In this place, my father, blessed be his memory, met his death. He was killed by the SS man, Green. This tractor (Bagger) plays a significant symbolic role in his death. He went under the Bagger, it was said of him, or of any Jew who had been murdered by the Germans, even if killed in some other spot and when someone would naively ask “what did you mean, he went “under the tractor,” they would answer him in an oblique manner and, no less symbolically: “haven’t you heard? He didn’t want to eat his “Hors d’oeuvres.”

At the site of the old wash house, they finally erected a huge and modern wash-house. It had about 200 showers, but it was possible to bath only at night, and then not always, due to the lack of water. The greatest problem in getting access to the water involved the location of the camp. It stood above the city, and at quite a distance from the municipal waterworks. In addition the main pipe was not suited to the amounts of water needed.

Once we had already sent our clothes into the “Entlausung” (delousing chamber) and had soaped our bodies with soda, and the soda had already begun to burn on our sores, over the millions of red spots where we had been bitten by bugs, fleas and lice, then it dawned on us, that neither was there enough water, nor was the water heated.

Under each shower, you generally had two people, and both would try to direct the water-flow onto their bodies, everyone in the hall shouting and raving “Wasser, Wasser.” (water, water) – but in vain, the “wasser” was in no hurry to arrive. Those in the know said the Germans deliberately turned off the main water tap. They said the Kapo for the showers was “just having fun.” Sometimes there was no need to even turn off the tap …. the water just didn’t arrive.

The “Entlausung” did not function properly either, the temperature never reached even the minimum required. Once, I forgetfully left a candle in the pocket of my striped jacket. I was apprehensive, fearing that the candle would melt in the great heat and that my only clothing would be stained, but the candle emerged unscathed from the test, and so did the lice, who were also alive and well.

Well gentlemen, as you can see, the road that once led to the “Leichen – Halle” is now closed. The electrically charged fence which surrounds the residential camp, runs through it. Please come on back to the “Frauen- Lager.”

On the left, you will note, the “Appell- Platz.” In the distance, set above “Berg – Strasse” rows of barracks standing out against a green mound in the background. There is silence all around, just birds chirping in the air, and from afar, we can hear the noise of trains, and the clatter of train cars…. wait, wait, those are not birds chirping, it’s wheels of the barrows grinding.

Here I can see them clearly now, through the “Appell-Platz,” a long line of shadows, dark and obscured, are advancing, pushing wheelbarrows… and in each barrow is a naked body, from its head, a trail of blood flows as it bounces back and forth across the whistling front wheel. I just noticed that’s not the rattle of a train engine, that’s the scream of the SS men.

All the Kapo’s shrieking at once “Mutzen ab!” Get into threes, get into threes” and down below to the side of the “Steinbruch” a black vehicle approaches, inside is the “Kommandant” wearing a white cap and a white sweater (not a good sign). The silence of death, under a layer of heavy cloud, conceals the rows upon rows of shaven heads, protruding out of their striped pyjamas…. “Hey you there, you dirty son of a bitch, don’t you hear? Do you want to go under the Bagger?”

I understand, suddenly, that the Kapo is addressing me…. “Oh, I’m sorry. No, no, it’s nothing. Nothing happened. I was just remembering something.” We are moving once again, now on towards the women’s camp.

The weather is fine today, it is peaceful, only the birds are chirping in the air, and from afar we can hear the noise of trains, and the clatter of train cars. We are presently entering the Jewish police station, the OD (15). The hut is located in the Women’s Section of the camp. The officer in charge of the OD was one Hilewicz, and his assistant was Finkelstein.

They were both killed, along with their families, a few months before the camp was dismantled. The OD men wore tailored uniforms of brown-green cloth, a round cap with a visor, over which ran a yellow stripe. In one cruel hand they wielded, always, their own personal weapon, a whip, accompanied always by loud and insulting curses, they kept order during the working hours, and with the aid of these whips and their curses, they sent forth innocent people to the “Selektionen” and the “Aktionen.”

Whip in hand and mouthing obscenities, they would take an active part in many of the tortures. Using a blow of the whip and their orders, which they issued in German, they assisted the SS men in the running of the daily parades and, whip in hand, they “tended” to the prisoners in the camp jail. For all their great services which they rendered to cruel Germany, they received, in payment, a double ration of soup, more cooking oil, an entire loaf of bread, two portions of jam, and the right to sleep with their women in special cells that afforded some privacy.

Once, while I was taking the map of the camp in to Hilewicz, the OD brought a man into the station. He was dressed in civilian clothing, a white shirt and tie, shoes tied with laces. It appeared that he had tried to run away from the camp, Hilewicz hit him, kicked him in the gut and shouted, “Gib a kik, a “meshuggener” (Take a look at this crazy).

I stood to one side and gazed at the poor man, who looked pretty normal to me. I looked at the strangers garb, and at all the other incongruities which surrounded me, and asked myself, “who indeed are the crazies here?” In the Frauen –Lager (women’s camp) there were 10 huts. Inside, they were arranged pretty much like the men’s huts. Three tiers of bunks, a stove and water pail in the fireman’s corner but behind the scenes, in both the men’s and women’s camps, besides their shared characteristics of murder, starvation and torture, they also had their romantic sides.

No particular attention was paid to sexuality. Who was able to even think about things like that? Still despite everything, life went on, and love was conscripted into the background. Logic would have dictated that in conditions where death lurked in every corner, to a fearful and trembling soul there would be scant opportunity for sentimental feelings.

When the SS caught a pair of lovers, even in the early stages of love-making, while they were just sitting on the bunk with their arms linked, or were standing embracing in a dark corner, only one outcome awaited them both, a shared death.

Any male who remained in the Women’s Camp after the gates were closed was put to death on the spot, and there is no need to elaborate about what happened to women who were pregnant. Pharaoh had wanted to kill only the male off-spring. He was not concerned about the females… Hitler improved on this system. He took it one step further by seeking to prevent Jewesses from even conceiving, murdered the infants along with their mothers. And yet, in this mine-field, still roses bloomed.

Once, while I was working in the “Bau-Leitung,” I was standing in front of the hut doing a sun tracing. I had directed the large frame with a sketch in it on which I was working, and inside which I placed some special paper which was sensitive to rays of sunlight, towards the cloudy skies… but the sun had refused to do me the honour of coming out from behind the drawing.

I was walking about, disappointed and frustrated. I did not know how I was going to explain to the Nazi “Bau-Leiter,” the expert in killing, but who was totally ignorant about engineering, how to explain to him, that without the sun, it was impossible to copy this important plan. At the fateful moment, a female clerk wearing a striped dress came out, stopped next to the frame which was still awaiting the sun’s ultra-violet rays, and asked:

“What are you doing?” “My dear lady” I answered, “I am waiting for the sun, and she refuses to come to me. Do you think that perhaps, in your kindness, you might stand in for her?” That is how I met my wife, Rifka.

On the following day, I brought her a bunch of wild flowers, hidden in my striped cap. I wanted to thank her for her help and to tell her that the tracings had been successful, but before I could open my mouth, one of the clerks grabbed the flowers, crumpled them nervously, quickly threw them into the wastepaper basket and chased me out of the office.

“Get out of here! You crazy! Don’t you know the “Kommandant” is in the next room?” A few days later I met Rifka standing in the soup line-up, I gave her my first kiss by the light of the moon, behind the latrines. After that, every morning, before the parade, I would bring her hot water from the kitchen to her hut and I would polish her shoes with cuff and sleeve.

In the camp, the male imprisoned covered their shaven heads with a white kerchief. I wore my cap, but in my pocket I would also carry a white kerchief – my free entrance ticket into the women’s compound.

My wanderings back and forth continued even during “Aktionen” and “Selektionen. “ A few times we came very close to being separated for good and on some occasions we were saved by a miracle, some very tricky situations… until one day, for four rations of bread, I purchased a silver spoon.

For an additional four rations of bread, a jeweller in the watch-workshop made up two rings from the spoon. That evening, next to my mothers bank, we organised a speedy wedding – in the complete absence of rabbi, wedding guests, or music, indeed with neither salad nor mayonnaise, nor any of the rest of the formal wedding requirements. I simply stated, “Behold thou art betrothen unto me.”

We received my mother’s blessing and with my newly wedded wife, I went off to her barracks- here to this hut, to celebrate my wedding night. We got onto the bunk on the third tier and with halted breath waited for the “lights out” – but on that very night the “Barraken- Altester” did not put out the lights because the Germans had arranged that a search for male prisoners be conducted in the women’s camp.

A strategic assessment of my situation convinced me it was already too late for me to escape, and that any verbal explanation would be of no avail. There remained only two choices, either to confront the present danger head on, or to deal with it through deception. My wife’s two bunk mates began covering me with all manner of rags and tatters and then the three of them feigned sleep. However, they did not really fall asleep, because of the frantic level of their own anxiety and because the pillow below their heads kept trembling with fear.

At the conclusion of the search, the agonised cries of two young guys, could be heard as they were beaten to death when the identity of their sex was discovered, I had been saved once more. While I was busily trying to change the manner and direction in which I was lying, from the entrance of the hut could be heard the trumpet call for morning parade in the men’s camp.

I jumped from the bunk with alacrity. At the run, I covered my head with the white kerchief and attempted to leave the women’s camp, but the gate was closed. I paused at the electrified fence, at a loss of what to do, out of hope and out of breath. I knew just one thing, if in another five minutes I had not shown up at the “Appell-Platz” this was to have been my last night on earth and that if I tried to climb over the fence, the results would likely to be just as bad, only that death on the fence would come more quickly and would be more honourable.

I chose a suitable interval when the beam of the searchlight had passed into the distance as it revolved away from me. I took my farewells from this cruel world in haste, from my life that had not even had the opportunity to commence, from my mother, my brother and from my wife, who was in a second, about to become a young widow…. and I jumped towards my death.

My fear must have lifted me clear over the buzzing wire and to this day, I do not understand how I was twice saved in a single night. When I appeared in my group at the “Appell- Platz,” they announced that the special parade had been cancelled.

We are now entering the “Frauen- Lager” via the main gate. We are descending some stairs made out of smashed marble tombstones. These fragments which still bear the names of those who were buried here, crunch beneath our feet, they beg to announce that their bones and their skulls, emptied of their gold fillings, now seek their final rest, beneath the wash-house, beside the bones which were riddled with bullets, and never afforded the luxury of a tombstone.

We are standing across from the laundry (23). Inside, they would wash the underwear, sweat-shirts and blouses of the victims of an “Aktion.” Before sending the loot off to the clothing warehouse, the blood and sweat stains were cleaned off, buttons were added for those that had come loose during their anxious disrobement and holes were mended where bullets had turn through them – since there must be Ordnung muss sein.

We the prisoners did not have anything to launder, we lived, walked and slept, always in the same bit of clothing and as for underwear and undershirts, shirts? – we had even forgotten what their use was. In brief, we didn’t have any “change of clothing.”

In the laundry there was a special service section for the SS team and the noble officer’s corp. One evening the “Kommandant” sent his white sweater for laundering. While it was drying, one of the women from the laundry detail sat on guard with it an entire night, staring at it all the while, only at the sweater that was hanging there ….. it must not be stolen, or fall to the floor, or who knows what.

Nothing should happen to that precious sweater – that it should be clean and dry when they came to get it next morning. And now the spiritual and commercial centre of the camp, the Latrines (27,32), two long units, each about 30 metres in length. Inside from both sides are uneven wooden boards, and in them 30 holes. In the middle of the Latrine, a sort of long trough, and above it, a pipe with several taps that didn’t always work.

In the morning before the parade, or at night after work, this is where all the residents of the camp would congregate. People would wash, or at least clean their teeth, at every available tap, while several waited in line. Around these some 60 men, and between their moans and groans they would tell each other the latest news and the most current jokes. Between them would pass “kibbetzers” who were waiting with ill-concealed impatience for those who were still sitting and spitting, to finish talking and go.

In the “Latrines” it was possible to meet old friends, and transact important business, it was possible there to exchange bread for cigarettes, or for sugar, and if one was so fortunate as to have some money, that lucky fellow was able to purchase even hard-boiled eggs, butter or soft and sweet candies, products of the bootleg and mysterious “Krowka” factory.

At times, in order to get the lazy ones out, the OD men would burst inside armed with their whips, or the SS men with their loaded revolvers, and then everyone would get out of there in an insane turmoil…. some of them running half naked and wet.

And in the middle of their blind gallop would still be trying to dry their faces with their fingers, some would run off without even a sense of direction, holding their pants in their hands still defecating as they ran and alongside, ran the “merchants” looking among those in flight, for their last customer, who had purchased something from them, but had not yet had time to pay for it.

Once, during the winter, the “latrine” was closed temporarily and a long line of would-be customers was waiting at the entrance. Suddenly, for a couple of seconds, the sun broke through a layer of clouds and without much thought cast a few rays of sunshine across the camp’s barracks.

One of the men standing in line for the “latrines” shut his eyes and turned his face towards the warmth. The SS man who happened by choice there, fell upon the “sunbather” slapped him across the face and shouted at him with contempt: “Die Sonne ist nicht fur Juden” (The sun does not shine for Jews). The “Villa” standing next to the “Latrina” is in fact the bakery. The building was built way back, before the flood. It used to belong to the Jewish community of Krakow and was used as a recreational spot for children.

In the early days of the camp, it used to be the “Kommandant’s” headquarters. When he moved into the “Red House” the building was converted into a bakery. Grunberg, the engineer, installed two baking ovens here, capable of baking 4,500 loaves a day – but the growth of the population consumed all that bread very rapidly… the liquidation of the ghetto’s in the vicinity and the transfer of the remaining refugees to Plaszow added more hungry mouths.

There was an urgent need to build an additional oven. Three ovens all together then supplied 24,000 imprisoned with 6,000 loaves of bread per day, which is to say, that every Jew received 250 grams of dry, heavy, dark-brown dough, baked in great haste from flour mixed with sawdust.

But hunger clouded our taste buds – we ate this bread of poverty with a relish, thinking that we were feasting upon festive honey-cakes. The bread stood at the peak of our wretched lives – our whole beings revolved around it. Bread was the “exchange commodity” at the stock exchange “latrines.” Bread was the price fixed on any article – we bought with bread… we earned our daily bread.

Once, in order to make the people work harder the “Kommandant” promised that we would all receive a “bonus” to our regular bread ration if we completed building the “Wach- Kaserne” on time, and indeed after the work was completed according to plan, we got the promised bonus – half a loaf of bread for each of us.

At that time the camp had a visit from an inspector of the Red Cross. When he entered the bakery and asked the Jewish baker how much bread each prisoner was getting every day, the “Kommandant,” who was standing behind this inspector, lifted two fingers above his head in order to assist the baker in making the right calculation.

Besides the bakery, in the same area, fenced in with barbed wire, stands the Kitchen (37). This is the most important structure in the whole camp. Here, in 60 cooking vats, food for all the striped ones was prepared according to a regular time-table. In the morning a mug of black and bitter water that was referred to as coffee, the afternoon, a litre of boiled water with a few lonely grits floating on the surface of the container. The colour of the soup depended on the amount of salt.

When the cooks added only a small amount of salt, the soup was light blue in colour, and on those times when they honoured us with enough salt to melt the snow, at those times we drank green soup. There were however some changes in the menu, there was one period when they distributed “sago” – small translucent balls, moist and runny with no colour, taste or smell – their shape reminded one of frogs eggs.

For desert they added to this banquet a teaspoon of jam, some purple and sour berries that had been left over in a factory manufacturing fruit drinks from raspberry concentrate. There was one very brief period when they suddenly opened up the storeroom and administered legal rations to us. People started getting diarrhoea from this abundance of calories.

For a whole week we gorged ourselves on yellow cheeses, citrus preserves, and condensed milk in aluminium cans. We fixed “goggle moggles” from fresh eggs and white sugar. We were given soup made with real meat, noodles but after this incomprehensible abundance, the black bread and “sago soup” soon re-appeared.

Once, I was passing the kitchen area and I noticed a few agitated people rushing about wildly at the entrance. They told me furtively that one of the vats had toppled over and spilled out all its contents onto the floor. Unfortunately, I did not have a container at hand. I quickly ran off to look for something that would do, and on the junk pile of the hospital (Kranken- Revier), I found an old discarded “night potty,” rusted and missing a handle.

I washed it off with sand and snow, attached a piece of wire for a handle and arrived back in time to scoop up the remains of the soup with my hands from the floor. Speaking about food, later on in Brunnlitz Camp, because of miserly rations of food, devoid of calories or vitamins, the prisoners there started turning into “musselmen” (walking skeletons covered with skin), home to the bugs and lice that lived in and on them.

I for example, weighed 34 kilos. You ask how I know my weight. The Germans would weigh us once a month in order to catch the wily ones that might have discovered some system of eating, which was keeping their weight up above the norm.

After the morning parades, the camp commander would rebuke us with the following:

“You are all a bunch of gluttons. According to my calculations you should have fallen behind two months ago. Apparently you are stealing food.” Gentlemen, we are now entering the “Kranken –Revier” (18, 19, 20). We gave this worthy institution the lofty title of “Hospital” but it was in fact the “sick people’s quarters.”

As the title of the place suggests, the Germans isolated all the sick here in order to prevent epidemics, and, in the event of a “transport” to the ovens of Auschwitz, not to have to seek unproductive people from their barracks.

The Nazi persecutors had never had any intentions of administering a hospital in the concentration camp – not even a first –aid station. Put more plainly one may define this public utility as the “death house.” Here, doctors, under the supervision of an SS officer, assisted the sick imprisoned to die more speedily. In their favour, however, I should add that at the time and at this place, dying in bed was to choose a “luxury” death.

And if someone nevertheless, and despite of it all, insisted on deluding himself and sought salvation here, please understand that, in the first place, under the established system of darkness, without medications, without needed supplies and without sanitation, it was impossible to provide medical attention at all.

In the main, the doctors and nurses would treat only injuries which were incurred through beatings, black eyes, fractured bones and broken arms. Neither did it follow that in every case after a sadistic attack the injured victim, even though he might be streaming with blood, be referred to the “Kranken – Revier” even for first aid.

Sometimes the “Kommandant” would send him to the stone quarry to heal his wounds through hard labour, or would simply shorten the man’s torture by providing him a merciful death with a bullet in the head and a kick up the arse. The two huts standing to the side (1,4) were reserved for those who were ill with contagious diseases. There, was only one treatment, only one, an injection of kerosene or benzine.

In the light of these very persuasive facts, people did their utmost not to fall ill, or at least to create that impression. Thus it was the number of brave visits to the “Kranken – Revier” was not very large. It is possible the nature of our starvation diet may have provided us with some measure of immunisation from the more conventional forms of illness.

It is equally possible that our bodies had become so injured to the cruelties which abounded that they had somehow overcome the weaknesses to which they might have been more vulnerable during “peacetime.” People simply “dried up,” their musculature adhered to their bones, their reservoir of strength was drained to its limits and despite their best intentions, they were rendered “work-evaders.”

And being “unproductive” as was self-evident, they were killed, hung, burnt or simply murdered in the name of the laws of Germany. Our clothing comprised only a striped jacket, made of light cloth, without lining, a cap from the same cloth, and wooden shoes without laces and no socks.

Shirts and underwear were not included in the basic clothing of a prisoner and along with other extras such as sweaters and coats were forbidden to the imprisoned. God forbid the Germans should discover that somebody was wearing some other article under his striped jacket. He would no longer be in need of anything to wear at all.

The corpses they threw naked into the ditch and their clothing was sent to the laundry and from there to the storage facility to be used once more. If a woman was wearing a brassier or panties, the SS men would daub her breast with red lacquer paint.

During heavy rains and gusting storms we walked about drenched to the bone…. during snowstorms we froze into pieces of ice and I don’t remember a single occasion when I caught cold or the flu. I never even had a runny nose. Perhaps I did in fact get ill, but caught up in the flood of other horrible afflictions, I didn’t even notice.

Once with the aid of a little bribery and at the cost of a loaf of bread, I got a chance to visit the dentist. I asked for a filling for a molar that was giving me pain. As soon as I sat down on the chair the SS man in charge of the “Kranken-Revier” came in and looked inside my mouth, and issued forth this edict “Take out his front tooth, No anaesthetic.”

And so it was. I was afraid to say a word and fearful to cry out when they dug out my front teeth, clean and healthy. Interestingly, from that time on, the pain in the rotten molar ceased forthwith.

Behind the “Kranken- Revier” is an open lot. Here, the Germans had planned to build a crematorium. Parts had already arrived and were being stored in the warehouse – but the heavy losses suffered by the “Master Race” never quite made it possible to construct this modern and efficient edifice, through which Hitler’s order for a “final solution” was to have been carried out.

Here we are moving up onto the most infamous hill in the camp, Hujowa Gorka. This place is rendered holy in the name of thousands of Jews who were murdered here by the Nazis by fire, the sword, by wild beast, by hunger, by thirst, by pestilence, by strangulation, by starving.

The crude nickname of this historic site is related to the SS man Hujar, who directed the “Aktionen” here. Perhaps with this crude definition the imprisoned sought to emphasise the lack of compassion and the scorn which a whole world displayed, in that it knew, and never responded.

By way of a common grave, the Nazis used two trenches that had remained in place since the First World War. In these pits they exterminated entire groups of people. The picture was the same most times. Those selected for execution from the first group would undress, deliver up their clothes, lay down upon a layer of unfinished boards set down upon the timbers, one next to the other and then, the Germans would open fire on them with machine-guns.

The condemned from the second group undressed, handed back their clothing, covering those not yet quite dead from the first group with a layer of wooden timbers, they lie down upon those same timbers…. afterwards comes a third group, then a fourth… and so the pyre bonfire is made ready. Whoever, is last pours the benzine and sets the conflagration alight…. then he too is killed, and thrown into the fire. People did not open their mouths, the Germans had shut their mouths tight with plaster.

Once, one of the candidates for the inferno was saved through a miracle. He escaped from “Hujowa Gorka” and related what the “Wachmanner” (Russian prisoners of war who collaborated with the Nazis) were doing. After a number of Jews from the “Bonarka” group had been annihilated, they raped the body of a murdered Jewish girl and stood in line shouting: “Quick, quick before she goes cold.”

This spot is the most elevated, from here you can see almost the entire camp. From here it is also possible to see the other side of the wire fence, a road and the houses of the free citizens of Plaszow.

In those days, during the national reign of “Kommandant” Goeth, we did not pause to contemplate the surroundings. We were the slaves of Hitler, enslaved at hard labour with all the terrible significance involved in constituting a caste of slaves and, in the role of slaves such as these among other forms of disenfranchisement, were deprived also of the right to “be idle.”

Whenever an undisputable order issued forth from even the most petty little clerk or German work-foreman which compelled someone to pass along this street, that someone did his utmost to run as quickly as possible and not to “see” too much.

Any chance meeting with someone wearing the deaths-head insignia on his cap compelled the Jew, the sub-human, to remove his striped cap, to stand at attention and to announce in a loud voice his personal number, what he was doing there and to where he was going.

An encounter such as this ended well if it concluded with only a kick in the backside or a brutal slap across the face. There was one other reason that prevented us from being awed by the panorama – each day there were “bonfires” on “Hujowa Gorka” and the stench of roasting human flesh cast a stifling odour and dense smoke which covered all the scenic wonders and blocked the whole world from our view.

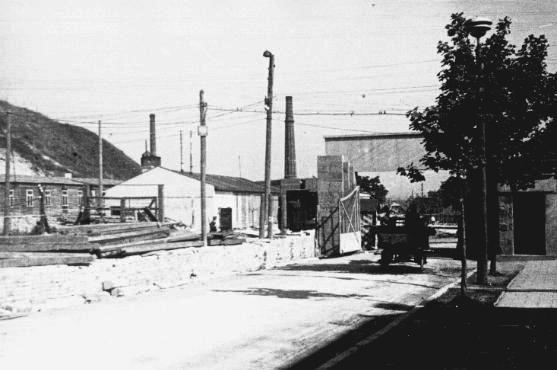

Today the camp is covered with silence. The tapping of hammers has died down. You no longer hear the sound of gunfire, or guttural German curses, or the noise of the machines in “Industrie Gelende” (Industrial Area).

When the camp was first started, when the well-oiled machine of war and destruction was grinding tens of thousands of Jews and their belongings beneath its wheels, during that period of total destruction without any perceivable end in sight, there was in the camp a very clever Jew, named Yizhak Stern who, with the aid of Mietek Pemper and along with Grunberg, the engineer, explained to “Kommandant” Goeth that his camp could be of great assistance to Germany in its contribution to the war effort.

Instead of killing the Jews, why not exploit them and their machinery which had been left behind in the ghetto. They could be used to produce armaments. This idea did not bring great rewards to the Nazi army, but it did save the lives of nearly 20,000 Jews who were already selected for the “Himmel –Kommando.”

In order to prepare the plan –specifications for the workshops that would be supplying the soldiers at the front, we worked in the “Bau-Leitung for some days and nights. The higher-ups in Germany had agreed to the suggestion and had begun sending in their orders …. and that’s how the workshops in the “Industrie Gelande” got started.

Over here, in the first row, next to the Berg Strasse, you see the locksmiths and tinsmiths hut (84) and next to them, the hut of the metal workers (89). Further down this row, is the central warehouse (81). Across from us, two huts, belonging to the carpenters (91, 94), the printers (92) and the brush factory (95). Later a new section was added to the “Industrie Gelande”, the “Neu Gelande,” 17 huts of tailors, furriers and upholsterers.

After some months, some fateful developments transpired there. The work camp was officially changed to a Concentration Camp. We were handed over from the cruel hands, of the zonal –police of Krakow district into the murderous grasp of the entirely German office of the SS- police.

The camp gained a lofty new title – “Konzentration- Lager – Plaszow” and the “Kommandant” got himself a more secure position without having to worry about being transferred to the front-line. Even the workshops came out ahead – they were already functioning properly and there was no longer any reason why they should be extending assistance to the army.

Accordingly, the workshops began performing with alacrity only those jobs which meant the independent needs of the camp, and also filled private orders from the SS officers and the officers in command at the very highest ranks.

The tailors in the “Mess Schneiderei” sewed custom suits, and the cobblers in the “Mess Schusterei” mended and made shoes for the “Kommandant,” his friends and their superiors. In the print shop they printed “bulletins” of the resistance for their agent provocateurs, notices of executions that had taken place and any manner of secret and other questionable documents.

In the central warehouse (“Zentral Magazin”), the property which they had looted from the Jews was stored and catalogued: camera’s watches, gold teeth, cooking utensils and more, as well as other aides-to living which had belonged to people who were no more, to people who had recently gone “under the Bagger” or to “Hujowa Gorka” or to people who had long since gone to their deaths.

That warehouse was the cause of “Kommandant” Goeth landing in a German prison, branded as a thief. According to an old Jewish proverb, he should have been found innocent, since, “he who steals from a thief is not liable” – but the high court of Germany was working under the mis-assumption that the Jewish treasures were the legitimate property of the Nazi people.

Meanwhile, the war had ended, and the “Kommandant” came to his end in a Polish prison where, after a brief trial, he was hanged. That’s about it gentlemen, you’ve seen almost the whole camp, but actually you saw very little indeed, merely a few droplets, a single drop in an entire ocean.

To tell of “Konzentrations – Lager – Plaszow” is almost like lifting up with one hand a huge skyscraper in which are concealed the sufferings and the torture of tens of thousands of Jews. We are descending now down “SS Strasse,” on the left the villas of the officers (177, 179, 181, 182,183) who assisted “Kommandant” Goeth in his notorious career.

Here is the “Red House” (178) which belonged to Goeth in which he lived and, in the end, in which he packed his boxes with Jewish treasures. At the rear of “Red House” the doggie –hotel (Hunde Zwinger) which housed the dogs trained to track down people wearing striped clothing.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

You can learn more about Joseph Bau [here]

Sources: Plaszow – (Unpublished Document) Robin O’Neil Drawings by Joseph Bau Holocaust Historical Society Ghetto Fighters House USHMM www.Gedenkendienst.org PK - Krakow

Copyright Chris Webb & Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T 2008

|