Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Other Camps

Key Nazi personalities in the Camp System The Labor & Extermination Camps

Auschwitz/Birkenau Jasenovac Klooga Majdanek Plaszow The Labor Camps

Trawniki

Concentration Camps

Transit Camps

|

|||||||

Buchenwald Concentration Camp

Buchenwald concentration camp was one of the largest on German soil, with one hundred and thirty satellite camps and extension units. The name “Buchenwald” was given to the camp by Heinrich Himmler on 28 July 1937.

Buchenwald was situated on the northern slope of Ettersberg, a mountain five miles north of Weimar, in Thuringen. The camp was established on 16 July 1937 when the first group of prisoners, consisting of 149 persons mostly political detainees and criminals was brought to the site.

Buchenwald was divided into three parts – the “large camp,” which housed prisoners with some seniority – “the small camp,” where prisoners were kept in quarantine and the “tent camp,” set up for Polish prisoners sent there after the German invasion of Poland in 1939.

Besides these three parts were the administration compound, the SS barracks and the camp factories. The commandants were SS- Standartenfuhrer Karl Koch from 1937 -1941, who later served at Majdanek and SS- Oberfuhrer Hermann Pister from 1942 until 1945. Other notable SS officers who served at Buchenwald:

Large groups of prisoners began to arrive in the camp shortly after its foundation and by the end of 1937 their number reached 2,561 most of them “politicals.” In the spring of 1938 the number of prisoners rose rapidly as a result of the operation against “asocial elements” the victims of which were taken to Buchenwald, by July 1938 there were 7,723 prisoners in the camp.

Another 2,200 from Austria were added on 23 September 1938, all of them Jews. A further 10,000 Jews were imprisoned after Kristallnacht – 9/ 10 November 1938 and at the end of November the camp prison population exceeded 18,000. By the end of the year most of the Jewish prisoners were released and the camp population had dropped to 11,000.

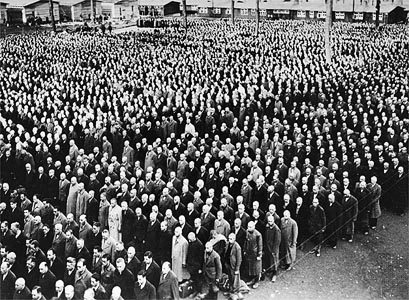

The outbreak of war was accompanied by a wave of arrests throughout the Reich, which brought thousands of political prisoners to Buchenwald. This was followed by an influx of thousands of Poles, who were housed in the tent camp. As of 1943 following the completion of armament factories in the vicinity of the camp, the number of prisoners grew steadily to 63,048 by the end of 1944 and to 86,232 in February 1945.

In the eight years of its existence from July 1937 to March 1945, a total of 238,980 prisoners from thirty countries passed through Buchenwald and its satellite camps, of these 43,045 were killed or perished in some other fashion there.

The German Jews that arrived in 1938 were subjected to extraordinarily cruel treatment, working fourteen to fifteen hours a day – generally in the infamous Buchenwald quarry – and enduring abominable living conditions.

The Nazis’ object at this point was to exert pressure on the Jews and their families to emigrate from Germany within the shortest possible time. Thus in the winter of 1938 -1939, 9,370 Jews were released after their families, as well as Jewish and international organisations, had made arrangements for their emigration. Of the Kristallnacht detainees, in the short time that these prisoners were held in Buchenwald, 600 were killed, committed suicide, or died from other causes.

The number of Jewish prisoners rose again after the outbreak of the Second World War, when Jews from Germany and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia were brought to the camp and by September 1939 the Jewish prisoners numbered some 2,700.

Resistance cells were formed in Buchenwald from the first years of its existence. In 1938 such a cell was established by members of the German Communist Party in the camp, who included some of that party’s most prominent figures.

At first the aim of the resistance cells was to plant their members in the central posts available to inmates, to support one another, and to have a say in developments within the camp. Up to the end of 1938 the internal administration of Buchenwald was for the most part, in the hands of the criminal prisoners.

When it was discovered that the criminals and some of the SS personnel were involved in corruption and stealing from the Kristallnacht prisoners, the camp administration removed the criminal prisoners from most of their posts, and their influence gradually passed into the hands of the political prisoners. Some resistance cells, mainly those belonging to the Left, managed to plant some of their members in key positions held by prisoners in the internal camp administration, thereby facilitating their clandestine facilities.

Later following the outbreak of the war and the influx into Buchenwald of political prisoners from the occupied countries, more resistance groups were formed on the basis of nationality. In accordance with an order issued on 17 October 1942, which ordered all Jewish prisoners held in the Reich to be transferred to Auschwitz concentration camp, all Buchenwald’s Jewish prisoners were deported to Auschwitz except for 204 essential workers.

In 1943 a general underground movement that included Jews came into being, called the International Underground Committee. The resistance movement in Buchenwald scored some impressive successes, primarily the acts of sabotage it carried out in the armaments works that employed Buchenwald prisoners. Underground members also smuggled arms and ammunition into the camp.

In 1944, transports of Hungarian Jews began coming to Buchenwald from Auschwitz concentration camp, after a short stay in the main camp most of them were distributed among the satellite camps, where they were put to work in the armament factories.

In August 1944 Wing Commander Yeo- Thomas, who was a British Air Force officer who was betrayed and captured in Paris in 1944, working with the French resistance, later awarded the George Cross, described his arrival at Buchenwald concentration camp:

About midnight their carriage was detached from the train and shunted along a side-line bordered by barbed-wire fences. On the platform of the station also surrounded by barbed wire an SS officer and SS guards were awaiting them. The Feldgendarmarie officer handed over to the SS officer a brief-case containing their documents and the latter took over command.

Under their new escort the prisoners were marched off through an unreal, pale, moonlit world. The ground crunched under their feet and occasionally there were weird howls from unseen dogs, but otherwise the night was silent and eerie. Faint lights appeared in the silver grey darkness and gradually grew brighter than the twinkling of the stars – they came from Miradors set up all around the camp in case any of the prisoners might be tempted to escape.

The darkness of a square building with a tower was thrown up into the sky against the lesser darkness of the night, and the prisoners were halted in front of an iron gateway bathed in pale mean light.

Guttural words were exchanged between the NCO in charge of their escort and an unseen guard behind the ghostly gate. Then the gate was opened and they were marched into a large compound surrounded by low huts lying in the darkness against a shimmering curtain of moonlight. Here was awaiting them another escort clad in what appeared to be a variant of the old Keystone comedy striped convict garb.

Light in this plain of macabre shadow came upon them with blinding suddenness, from electric bulbs hanging from the roof of a huge hall into which they were pushed by the warders, whose grotesque clothing they now saw clearly for the first time: clad in blue and white vertical striped suits and dark berets, these tough and expressionless officials wore black armbands on which was lettered in white “Lagerschutz, “ but to make it quite plain that they too, were men under authority, on their jackets and on their trousers were red triangles with numbers on white tapes sewn on below the triangles.

The prisoners were led into a long room, made to lay their belongings on a long table and lie down on the cold tiled floor to sleep. Ordered to undress they were then marched into a large room fitted with shower baths, beneath which they washed themselves with a gritty, lather-less soap

When they had dried themselves with rags they were moved on into another room, from whose ceiling a number of electric clippers hung on long wire. Under each clipper was a stool and behind each stool stood a striped barber, himself completely shorn except for a long tuft of hair running from his brow to the back of his head.

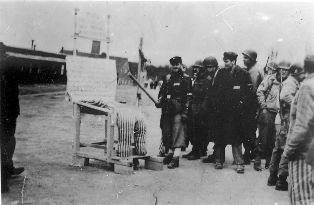

They were then taken to the quartermaster’s store where they were issued with their prison uniforms, multiform in their incongruity: Tommy received a pair of blue and white striped underpants with long lacing legs, a pair of old grey trousers tailored for a man six foot tall and weighing twenty stone, a faded blue mechanic’s jacket with sleeves which came down to his elbows and a back which barely reached his waist, a striped forage cap , a pair of wooden clogs and a white night-shirt trimmed with red round the neck.

Then they paraded in front of a middle-aged and shifty- eyed Schreiber who filled out their identity forms in accordance with their answers to his questions. When he noted their particulars the registrar issued them with number tapes and red triangles to sew on their jackets and trousers – Yeo –Thomas was given the number 14,624.

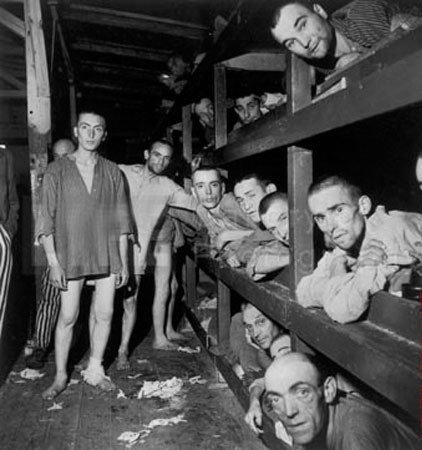

It was broad daylight by the time these processes were accomplished. As they were marched across the camp the prisoners had their first glimpse of their fellow inmates, and it was anything but reassuring. The compound was filled with emaciated, hairless wretches shuffling wearily round and round in heavy wooden clogs. The eyes of those listless sub-human creatures were mean with terror.

On the faces of many of them a sticky stream of yellow rot oozed from purulent sores set in the middle of purple weals. Others were so weak that they staggered as they walked.

Even when their clothes were too short for them they were too wide because of the thinness of the frail bodies which they covered. The new prisoners, too, had difficulty in walking, because they were not used to their loose- fitting clogs, and they stumbled and staggered across the rough stony ground.

They were glad when they were halted before and then marched into a hut surrounded by barbed wire – on the outside of the hut was the number 17. This hut was really not so much a hut as a block with wings. At the entrance was a small corridor, with a washing room with troughs and a circular basin on one side and a lavatory with urinals and latrine pans on the other.

The room in which the Blockaltester took their names and numbers had also the appearance of public-school comfort, fitted with rows of lockers and furnished with a number of trestle tables and a partitioned –off- cubicle for the Blockaltester.

But their own dormitory which was situated in another wing of the block was much less luxurious and consisted of three tiers of long rows of bunks set two by two. Two men were to sleep in each bunk. The palli-asses were only half-filled with straw and the blankets, of which there was only one to each bunk, were dirty and long enough to cover only half a man.

Beginning on 18 January 1945 when Auschwitz and other camps in the East were being evacuated, thousands of Jewish prisoners arrived in Buchenwald. The Auschwitz evacuees included several hundred children and youths, and a special barracks which came to be known as “Children’s Block 66,” was put up for them in the tent camp.

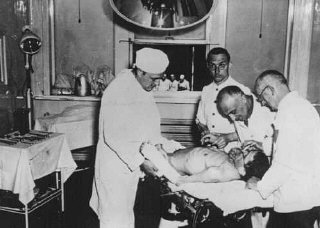

This block housed more than six –hundred children and youths, most of whom survived. The Jewish prisoners were deprived of the privileges and exemptions granted to the other inmates, and Jewish prisoners were used for medical experiments. On 6 April 1945, the Germans began evacuating the Jewish prisoners. The following day, thousands of prisoners of various nationalities were evacuated from the main camp and the satellite camps.

Of the 28,250 prisoners evacuated from the main camp, 7,000 to 8,000 either were killed or died by some other means in the course of the evacuation. The total number of prisoners from the satellite camps and the main camp who fell victim during the evacuation of Buchenwald is estimated at 25,500.

In the final days of the camp’s existence, resistance members who held key posts in the internal administration sabotaged SS orders for evacuation by slowing down its pace, and as a result the Nazis failed to complete the evacuation.

By 11 April 1945 most of the SS men had fled from the camp. The underground did not wait for the approaching American forces to take control but did so themselves, together with armed teams of prisoners, in the process trapping several dozen SS men left in the camp.

On that day, 11 April 1945 some twenty-one thousand prisoners were liberated in Buchenwald, with four thousand Jews among them, including about one thousand children and youths.

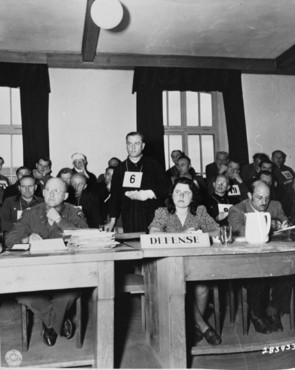

In 1947, thirty one members of the Buchenwald camp staff were tried for their crimes by an American court. Pister, his deputy Max Schobert, Krautwurst and Wolff were condemned to death and hung, resulting from evidence given by Yeo-Thomas.

Sources:

Encyclopedia of the Holocaust - Israel Gutman (Ed) - New York 1990. Robin Cohen’s Family Album of Photographs. The White Rabbit by Bruce Marshall, published by Book Club Associates 1984 Holocaust Historical Society USHMM

Copyright CW & Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T 2007

|