Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Other Camps

Key Nazi personalities in the Camp System The Labor & Extermination Camps

Auschwitz/Birkenau Jasenovac Klooga Majdanek Plaszow The Labor Camps

Trawniki

Concentration Camps

Transit Camps

| ||||||||||

Auschwitz Concentration Camp Pery Broad – SS Man The following pages are extracts from the reminiscences of Pery Broad Member of the SS personnel in Auschwitz Concentration Camp.

Gas

One day corpses of Russian prisoners of war were dragged out of a dark cell. As they lay in the yard they looked strangely bloated and had a bluish tinge, though they were relatively fresh. Several older prisoners who had been through World War One remembered seeing corpses like that. Suddenly they understood …. Gas.

The first attempt at the greatest crime, which Hitler and his helpers planned and committed in a frightening way, never to be expiated was successful. The greatest tragedy could then begin, a tragedy to which millions of happy people, innocently enjoying their lives, finally succumbed.

From the first company of the SS Totenkopfsturmbann, stationed in the Auschwitz Concentration Camp, SS Hauptscharfuhrer Vaupel selected six particularly trustworthy men. Among them were those who had been members of the Black General SS for years. They had to report to SS-Hauptscharfuhrer Hossler.

After their arrival Hossler cautioned them to preserve the utmost secrecy as to what they would see in the next few minutes. Otherwise death would be their lot. The task of the six men was to keep all roads and streets completely closed around an area near the Auschwitz crematorium.

Nobody should be allowed to pass there, regardless of rank. The offices in the buildings from which the crematorium was visible were evacuated. No inmate of the SS garrison hospital was allowed to come near the windows of the first floor, which looked onto the roof of the nearby crematorium and the yard of that gloomy place.

Everything was made ready and Hossler himself made sure that no uncalled- for persons would enter the closed area. Then a sad procession walked along the streets of the camp. It had started at the railway siding, located between the garrison storehouse and the German Armaments Factory (the siding branched off from the main railway line, which led to the camp).

There at the ramp, cattle vans were being loaded, and people who had arrived in them were slowly marching towards their unknown destination. All of them had large yellow Jewish stars on their miserable clothes.

Their worn faces showed that they had suffered many a hardship. The majority were elderly people. From their conversation one could gather that up to their unexpected transportation they had been employed in factories that they were willing to go on working and to be as useful as they could.

A few guards without guns, but with pistols well hidden in their pockets, escorted the procession to the crematorium. The SS men promised the people, who were beginning to feel more hopeful that they would be employed at suitable work, according to their occupation.

Explicit instructions how to behave were given to the SS men by Hossler. Previously the guards had always treated new arrivals very roughly, trying to keep them at “arms length” with blows, but there were no uncivil words just now. The more fiendish the whole plan.

Both sides of the big entrance gate to the crematorium were wide open. Suspecting nothing the column marched in, in lines of five persons, and stood in the yard. Somewhat nervously the SS guard at the entrance waited for the last man to enter the yard. Quickly he shut the gate and bolted it.

Grabner and Hossler were standing on the roof of the crematorium. Grabner spoke to the Jews, who unsuspectingly awaited their fate. “You will now bathe and be disinfected, we don’t want any epidemics in the camp. Then you will be brought to your barracks, where you’ll get some hot soup.

You will be employed in accordance with your professional qualifications. Now undress and put your clothes in front of you on the ground.”

They willingly followed these instructions, given them in a friendly, warm hearted voice. Some looked forward to the soup, others were glad that the nerve-racking uncertainty as to their immediate future was over and that their worst expectations were not realised. All felt relieved after their days full of anxiety.

Grabner and Hossler continued from the roof to give friendly advice, which had a calming effect upon the people. “Put your shoes close to your clothes bundle, so that you can find them after the bath.”

“Is the water warm?”

“Of course, warm showers – what is your trade?

A shoemaker ?

“We need them urgently, report to me immediately after.”

Such words dispelled any last doubts or lingering suspicions. The first lines entered the mortuary through the hall. Everything was extremely tidy. But the special smell made some of them uneasy. They looked in vain for showers or water pipes fixed to the ceiling.

The hall meanwhile was getting packed. Several SS men had entered with them, full of jokes and small talk. They unobtrusively kept their eyes on the entrance. As soon as the last person had entered, they disappeared without much ado. Suddenly the door was closed. It had been made tight with rubber and secured with iron fittings. Those inside heard the heavy bolts being secured. They were screwed too with screws, making the door air-tight.

A deadly paralysing terror spread among the victims. They started to beat upon the door, in helpless rage and despair they hammered on it with their fists. Derisive laughter was the only reply. Somebody shouted through the door, “Don’t get burnt, while you make your bath.”

Several victims noticed that covers had been removed from the six holes in the ceiling. They uttered a loud cry of terror when they saw a head in a gas-mask at one opening. The “disinfectors” were at work. One of them was SS Unterscharfuhrer Teuer, decorated with the Cross of War Merit.

With a chisel and a hammer they opened a few innocuous looking tins which bore the inscription “Zyklon, to be used against vermin. Attention, poison. To be opened by trained personnel only.” The tins were filled to the brim with blue granules the size of peas.

Immediately after opening the tins, their contents were thrown into the holes which were quickly covered. Meanwhile Grabner gave a sign to the driver of a lorry which had stopped close to the crematorium. The driver started the motor and its deafening noise was louder than the death cries of the hundreds of people inside, being gassed to death.

Grabner looked with the interest of a scientist at the second hand of his watch .Zyklon acted swiftly; it consists of hydrogen cyanide in solid form. As soon as the tin was emptied, the prussic acid escaped from the granules.

One of the men, who participated in the bestial gassing, could not refrain from lifting for the fraction of a second, the cover of one of the vents and from spitting into the hall. Some two minutes later the screams became less loud and only an indistinct groaning was heard.

The majority of the victims had already lost consciousness, two minutes more and Grabner stopped looking at his watch. There was complete silence, the lorry had driven away. The guards were called off and the cleaning squad started to sort out the clothes, so tidily put down in the yard of the crematorium.

Busy SS men and civilians working in the camp were again passing the mound, on whose artificial slopes young trees swayed peacefully in the wind. Very few knew what terrible event had taken place there only a few minutes before and what sight the mortuary below the greenery would present.

Some time later, when the ventilators had extracted the gas, the prisoners working in the crematorium opened the door to the mortuary. The corpses, their mouths, wide open were leaning on one another. They were especially closely packed near to the door, where in their deadly fright they had crowded to force it.

The prisoners of the crematorium squad worked like robots, apathetically and without a trace of emotion. It was difficult to tug the corpses from the mortuary, as their twisted limbs had grown stiff with the gas.

Thick smoke clouds poured from the chimney – this was the beginning in 1942. Transport after transport vanished in the Auschwitz crematorium, day after day. Victims began arriving in ever greater numbers and the murdering had to be organised on a grand scale. The mortuary proved too small for such quantities. The cremation took too long.

And Hitler was impatiently awaiting the extermination of millions of Jews from France, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Poland, Greece, Italy, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Jews kept coming in cattle vans from transit camps such as Verne, near Paris, Westerbork in Holland, Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia, Antwerp, Warsaw, Salonika, Cracow, Berlin, later also Budapest.

So Birkenau had to be enlarged – a year later things had already changed.

The Two Little Farmhouses

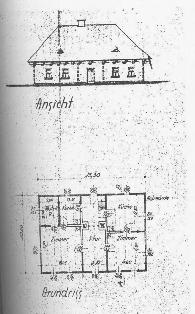

At some distance from the Birkenau camp, which was growing at an incredible rate, there stood, amongst pleasant scenery, two pretty and tidy looking farmhouses, separated from one another by a grove. They were dazzlingly whitewashed, cosily thatched and surrounded with fruit trees of the kind that usually grew there. Such was the first hasty impression. Nobody would have that it credible that in those insignificant little houses as many people had perished as would have filled a city.

The attentive spectator might have noticed signs in many languages on the houses. The signs read: “To disinfection.” Then he might observe that the houses were windowless, but had a disproportionate number of remarkably strong doors, made air-tight with rubber and secured with screwed down bolts, with small wooden flaps were fixed near the bolts.

Near the small houses there were several incongruously large stables, such as was used in Birkenau to accommodate prisoners. The roads leading to them bore the tracks of many heavily loaded vans.

If the visitor discovered in addition that from the doors there led a van track to some pits, hidden by brushwood fences, then he would certainly guess the houses served some special purpose. The NCO on duty crashed his way through the buildings occupied by the commandant’s staff. A whistle sharply shrilled through the silent night. “A transport has arrived.”

Tired and cursing the SS men jumped from their beds, covered with the finest eiderdowns. There were the drivers, employees of the section receiving new transports and of the prisoners property stores, the camp leaders and disinfectors, all of were on duty that night to receive new transports.

“Verflucht nochmal – these transports keep on arriving all the time, not a moment’s rest, where does this one come from?” “I think it’s from Paris. But there is one from Westerbork already in the station, we must push it quickly to the siding. A big transport from Theresienstadt has been reported due to arrive early in the morning.

Hell – that lot in Lublin don’t work anymore it seems. Everything comes to us. Well let’s hope the Frenchmen have at least brought plenty of sardines with them.”

They had meanwhile dressed. Motorcycles were being started up in front of the barracks and were driving away. Six large lorries had left the garages and were driving towards the transport ramp in Birkenau. The medical orderlies were driving in an ambulance. Driving through the rutted roads made some tins loose. They bounced on the floor of the ambulance, their labels read: Zyklon. The sleepy disinfectors cowered on the side benches. Round gas mask containers which hung above their heads, noisily struck one another.

SS- Oberscharfuhrer Klehr was sitting in front beside the driver, his steady work with arriving transports had won him a KVK (War Merit Cross). The ambulance proceeded straight to the innocuous looking farmhouses, “the bunkers” as those gas chambers were generally called.

Meanwhile the lorries had come up to the ramp. A long train consisting of closed freight cars was standing at one siding of the shunting yard. The doors of the cars were fastened with wire. Flood lights threw a glaring light on the train and the ramp. Anxious faces were visible in the small hatches, which were barred with barbed wire.

The sentries had taken their positions around the train and at the ramp. Their commander reported to the SS leader, responsible for the reception of the transport, that all sentries were on guard. The cars could be unloaded.

The commander of the escort squad which had guarded the train on its journey, usually a police officer, handed over the transport list to the SS man of the receiving squad. The list contained the name of the place where the transport had come from, the number of the train, and the names, surnames and dates of birth of the Jews brought to Auschwitz.

The SS men of the camp garrison had meanwhile made the newcomers get off the train. A pell-mell of all colours could be seen on the ramp. There were smart Frenchwomen in fur coats and silk stocking, helpless old men, children, their heads in curls, old grannies, men in their prime, some wearing fashionable suits, others in workmen’s clothes.

Mothers with infants in their arms were alighting together with sick persons, who had to be carried by helpful people. First of all the men and women had to be separated, amidst heart-breaking scenes of farewell. Husbands were separated from their wives, mothers waved goodbye to their sons for the last time.

Both columns were made to stand on the ramp in lines of fives, several meters apart from one another. If someone, unable to restrain his pain at the separation from his beloved, once again ran over to the other column to press the hand of, or say a few consoling words to his dearest, an SS man would brutally hit him and make him go back to his column.

The SS doctor then began to segregate those fit for work from those he considered unfit. Mothers with babies were unfit as a rule. Just as those who had impressed him as being weak or sickly. Portable wooden step-ladders were brought to the rear of the lorries. The SS men of the receiving squad counted all those who climbed in. They also counted the persons fit for work, who then had to march on to the camp for men, or for women.

The entire luggage was to be left on the ramp. The prisoners were told, it would be brought later by vans. This was true, but the prisoners would never see their property again. All their belongings would be sent to safes, stores and canteens of the camp administration.

Smaller bags with personal things as well as their clothes would be taken from them on entry to the camp. These poor victims of the frenzied drive to destroy presented an unspeakable misery after they had left the camp sauna.

Once fashionable and lively women and girls, they now had their heads shorn and a prisoner’s number tattooed on their left forearms – and they were clothed in sack-like blue and white striped smocks. The majority of them soon broke down, unable to bear the hardships of their fate.

The lorries with all those, who were not to be used for work in the camp had meanwhile departed. The SS men were asked what the big fires, visible from afar, were for. Their replies were not very reassuring. Most of them took little pains to keep the prisoners in the dark as to their future.

The continuous radio messages from abroad, telling about conditions in Germany, meant that the unhappy people partly foresaw what was in store for them at Auschwitz. But many of them could not bring themselves to believe, not till their last moments, that Germans who liked to represent themselves as a nation of philosophers and poets to the world could be capable of such barbarous deeds.

The prisoner’s squad was now busy at the ramp, loading the scattered trunks and boxes into lorries. The engine driver, instead of taking the empty train from the siding, tried to stay on the ramp as long as possible. He kept hammering around the inside of the locomotive, watching for a favourable opportunity to snatch some food or valuables scattered on the ramp. In a business- like way the SS men of the receiving squad compared their total of the arrivals with the number on the list. A small difference would be of no importance. A small note would be put next morning under the glass cover of Grabner’s desk. It was quite laconic.

Arrivals on ….. with transport No….. 4722, fit to work 612, unfit to work 4110.

Each SS man then got a slip for his special ration and vodka, one fifth of a litre for every transport. No wonder that alcohol was freely flowing in the commandant’s staff mess. The higher camp officials, the prominent leaders got special ration cards too, even if they had nothing to do with a transport.

The ramp was soon deserted and empty, except for the wooden step-ladders which hundreds of thousands of people had mounted, people whose lives were shortly to end, in matter of minutes only. The lorries had been driving back and forth several times in order to bring all those who were condemned to die to the bunkers. The people had to undress in the stables and were then crowded into the gas chambers.

The inscriptions pointing to “disinfection” the talk of the SS men and, above all, the pleasant look of the little farmhouses had many times made those who were about to die feel hopeful. They expected to be employed at some less heavy work, suited to their physical condition.

But it also occurred that whole transports were fully aware of their impending fate. The murderers had to be very careful in such cases. Otherwise they could be shot with their own pistols, as had happened in the case of SS-Unterscharfuhrer Schillinger. From the moment when everybody had been locked n the gas chambers and the doors bolted, the task of the majority of the SS men was over. Just as in the old Auschwitz crematorium, the “disinfector” now had to do his job.

Only the sound of lorries was not considered necessary here. The SS authorities in question probably did not realise that the inhabitants of the small village of Wola, situated not far from there across the Vistula, had often witnessed the scenes of terror at night.

Thanks to the bright frames from the pits, where corpses were continually burnt, they could see processions of naked people marching from the barracks, where they had undressed, to the gas-chambers. They heard the cries of people, brutally beaten because they did not want to enter the chambers of death, they also heard the shots which finished off those who could not be squeezed into the gas chambers, which were not roomy enough.

In the daytime Polish civilian workers were busy building big new crematoria, in the vicinity of the farm-houses used as gas chambers. They worked within the camp area, at a distance of several hundred metres from the farm-houses, so they were able to see prisoners tugging objects from the doors, loading lorries and driving them to the pits, over which clouds of smoke were forever hovering.

Specialists in this kind of work laid a thousand or more corpses, layer upon layer in the pits. Layers of timber were placed between the corpses, and then the “open air” theatre. was set on fire with methanol. The SS men in Auschwitz murdered systematically and with pleasure, but they were just as eager to fill their pockets.

When a gas chamber had been opened and ventilated and the corpses dragged outside by the prisoners who were forced to perform this horrible job, then one of the SS criminals detailed to the gruesome task began to extract gold teeth from the jaws of the corpses, using a special tool. He collected them in a pot.

Even the hair, shorn in the sauna from the heads of the new arrivals, was converted into money. If one asked an SS man, pointing to the corpses of men and women lying on the ground together with the children who lay as if asleep, why these people had to be exterminated?

Then as a rule one got the answer, “It must be so.” And that answer seemed, in his opinion, to be quite conclusive. Such was the influence of propaganda, which found with them an only too eager acceptance, due to their sadistic tendencies, to their megalomania and their intellectual limitations. These creatures, who hardly deserved to be called men, considered themselves the representatives of a highly developed race fully entitled to deprive members of another race of the right to live, more, to exterminate them by all possible means.

They did not regard Jews as human beings, the proverb Des einem Tod ist des anderen brot was never better illustrated than in the extermination camp Auschwitz. The thugs of Auschwitz enjoyed a life of comfort and pleasure till 17 January 1945, when the advancing Soviet Army put an end to their gruesome deeds.

Key Biographical Details of some of the SS men mentioned above

Pery Broad

Pery Broad was born on 25 April 1921, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the son of a Brazilian businessman and a German woman. Soon after his birth his mother took him to Germany, his father remained in Brazil.

He attended primary and secondary schools in Berlin. As a reward for his early membership in the Hitler Youth, he was awarded a gold membership pin. He graduated from high school in December 1940 and attended the Technical College of Berlin until December 1941when he had to leave, because he could not get his Brazilian passport renewed and residence permits were no longer being granted.

He volunteered and was put into the Waffen-SS, because of his myopia he was sent to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp instead of to the front. He was assigned to guard duty at first but in June 1942 he was transferred to the Political Section, where he stayed until the evacuation of the camp.

On 6 May 1945 he was taken prisoner by the British near Ravensbruck, after his release from internment by the British between 1947 and July 1953 he worked in the offices of a sawmill in Munsterlager and with a manufacturer of electrical equipment located in Brunswick, at whose Dusseldorf office he was last employed before his arrest prior to the Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt, where he was found guilty of war crimes, and sentenced to four years hard labour.

Maximilian Grabner

Maximilian Grabner was born on 2 October 1905 in Vienna, Austria. He worked in Kattowitz in the State Police Office, and was then transferred to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp, where he was head of the camp’s Political Section. He held this post until 1 December 1943 when he was arrested for corrupt practices and a special SS court sentenced him to 12 years imprisonment in 1944.

After the war he was tried in Krakow by The Supreme National Tribunal with other senior members of the Auschwitz – Birkenau camp staff, and found guilty of war crimes. He was executed on 12 December 1947.

Franz Hossler

Franz Hossler was born on 4 February 1906 in Oberdorf, Germany. He was manager of the camp kitchen in the main camp during 1940 -1941 and also Rapportfuhrer for a short time. In 1942 he commanded the prisoners’ squad at Miedzybrodzie near Zywiec, where prisoners built a rest home for the SS, known as Sola Hutte.

Between 1942 and 1943 he commanded various prisoners’ squads, among them the Sonderkommando, then he worked in the Employment Section.

From 27 August 1943 to January 1944 he was camp leader of the women’s camp at Birkenau, he was then transferred to Dachau, where he commanded a squad in one of the local sub-camps till June 1944, when he returned to the main camp at Auschwitz, as base camp leader until the evacuation.

In 1945 he was a member of the garrison at Mittlebau – Dora, after the evacuation of this camp in April 1945 he was transferred to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where he was captured by the British. He was tried for war crimes after the war and was found guilty and executed on the 13 December 1945 at Hameln.

Josef Klehr

Josef Klehr was born on 17 October 1904 in Langenau, Upper Siliesia, the son of a teacher at a reform school. After completion of his compulsory schooling he was apprenticed to a carpenter.

In 1932 he joined the General SS “because of economic hardships.” In 1934, he applied for a job at his father’s institute, but there was no vacancy. However, he finally did get a job there as a porter.

At the end of 1934 he took a job as a male nurse in a Silesian nursing home, and in mid-1938 he became an assistant prison guard at Wolhau. He went into the Waffen –SS after receiving his induction notice in August 1939.

He reached Auschwitz after stints in Dachau and Buchenwald. There he was assigned to the medical corps and was detailed to what he calls the “disinfection department.” During his time at Auschwitz he conducted selections and murdered untold numbers of prisoners by injecting phenolic acid into their hearts.

After the evacuation of the camp he served briefly in Czechoslovakia, and on 2 May 1945 he was taken prisoner by the American forces in Austria. His SS membership earned him a three and a half year labour camp sentence by the Goeppingen de-Nazification court, but he won on appeal against the sentence.

Thereafter he worked as a carpenter in Brunswick. Arrested and brought to stand trial in Frankfurt, the Auschwitz trial, Klehr was found guilty of war crimes, and sentenced to life and an additional fifteen years hard labour.

Sources:

KL Auschwitz Seen by the SS – Published by Panstwowe Muzeum w Oswiecimiu 1978 Auschwitz – Nazi Extermination Camp, Interpress Publishers Warsaw 1985 The Camp Men by French L. Maclean, published by Schiffer Military History, Atglen PA 1999. Auschwitz by Bernd Nauman, published by Pall Mall Press London 1966 SS Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum Archives.

Copyright F. J Frasier H.E.A.R.T 2008

|