Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Other Camps

Key Nazi personalities in the Camp System The Labor & Extermination Camps

Auschwitz/Birkenau Jasenovac Klooga Majdanek Plaszow The Labor Camps

Trawniki

Concentration Camps

Transit Camps

| ||||

The Destruction of the Jews of Greece

The declining Jewish population in Greece in 1941 probably did not exceed the 67,200 of the 1931 census. In 1945 the officially registered survivors numbered rather more than 10,000

If the Germans believed in March 1943 that they were saving Greece from Jewish strangulation, they could have spared themselves the trouble, for this was a fast-dying community.

Two- thirds of Greek Jewry lived in Salonika, the only Spanish Jewish settlement of Turkish times to prosper and expand since the creation of the Greek kingdom. Yet, in the twentieth century, the Salonika Jews declined.

In 1900 when they numbered 80,000 they constituted nearly half the cities population.

On 9 April 1941, Salonika, on the eve of the German occupation had probably 260,000 inhabitants only 46,000 of them Jews. Emigration had been forced by poverty and also by a certain degree of anti-Semitism, which became stronger after the expulsion of the Turkish population In 1923-24.

But Salonika was not a place where the Germans could count on the native population doing their work for them. This is shown by the fact that they hesitated to apply the Final Solution till a year after the first murderous Jewish deportation trains had left France and Slovakia.

Apart from the usual arrests of Jewish notables and the conversion of the Jewish Community Council into something resembling a German –appointed Judenrat, there were no specific anti-Jewish decrees till July 1942

Yet, in the winter of 1941 the Salonika Jews were scarcely better off than their brethren in the starving ghettos of Poland. The invasion had deprived Greece of her normal produce exchange of dried fruits, tobacco, and olive oil against wheat.

In November famine was already in sight. Although in March 1942 the British Government sent some wheat shipments – under safe conduct from the enemy- to Athens, 20,000 of the Salonika Jews starved and there was an outbreak of spotted typhus.

This situation did not prevent the German administration office of the “Salonika – Agais Command” decreeing in the month of July heavy labour conscription for all Jewish males from eighteen to forty-five years old. But the Todt Organisation had difficulty in finding three or four thousand men for railway construction among this debilitated mass of people.

Consequently, in October, exemptions were freely sold, and finally Dr Alfred Merten, counsellor to the Military Administration, stopped the conscription on payment of a community fine of 2,500,000 drachmas.

The Germans began the Final Solution in Salonika, as they had begun it in Poland, by destroying the vestiges of Jewish history, the archives and liturgic scrolls, and finally the grave-stones. These were removed for road-metal from the great Salonika cemetery on 6 December 1942, when SS- Sturmbannfuhrer Wulff of Eichmann’s office was making a preliminary survey.

Shortly afterwards Eichmann was said to have paid a brief visit, bringing his adjutant Rolf Gunther. The deportations were to be carried out by Dieter Wisliceny, who arrived from Vienna with Anton Brunner on 6 February 1943.

The preliminary steps were now taken in quick succession, the order to wear the Jewish badge, on that very day and the creation of a ghetto three weeks later – in fact three ghettos, one of them the “Baron Hirsch” quarter to which Jews were brought from the Macedonian hinterland being enclosed.

This place was a hutted camp near the railway station, which had been constructed in the year 1903 for Jewish refugees from the Mogilev and Kishinev pogroms to be inhabited subsequently by 2,000 of the poorest Salonika Greeks.

While the changes were taking place at “Baron Hirsch” Wisliceny and his associates established themselves in two Jewish villas in the Hodos Velissariou, which they proceeded to get up like a Port Said brothel.

The Jews of Salonika failed to realise the importance of Wisliceny’s arrival and the evil his presence boded, though on 14 March 1943 they were informed that the 2,800 country Jews in “Baron Hirsch” were to go to Krakow.

A train of forty box-cars transported them away on the following day – it did not arrive in Auschwitz till 20 March 1943. Following the selection 417 men and 192 women are admitted into the camp. 2191 people are killed in the gas chambers.

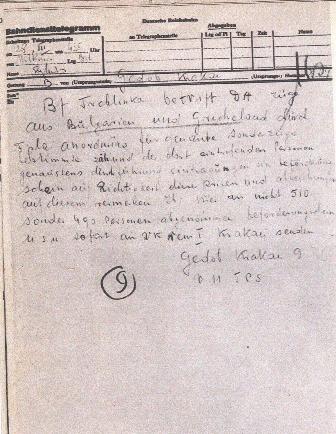

The next transport from “Baron Hirsch” was traced by a commission of inquiry at Siedlce in 1945 to the death camp Treblinka where it arrived on 26 March 1943.

Henceforward “Baron Hirsch” was filled, emptied and refilled every three days, so that by the end of March 1943, 13,435 Jews had been shipped out in five trains.

By the middle of May, when the Organisation Todt labour conscripts were moved, the great bulk of Salonika Jewry departed 42,830 people in sixteen trains.

The 1,000 –mile journey to Auschwitz or the 1200 mile journey to Treblinka took from five to nine days. Food was supplied to the deportees for ten days, chiefly bread, dried fruit and olives. Wisliceny stated at the Nuremburg War Crimes trial that the food and trucks were provided by the Transport Command of the Wehrmacht.

Samuel Willenberg an inmate of Treblinka witnessed the arrival of a transport from Salonika:

“During those days of March 1943, a train’s whistle signalled the arrival of a new transport. This time a most strange crowd issued forth from the cars. The new arrivals with tanned faces and jet black curly hair, spoke among themselves in an unrecognizable language. The baggage they took with them from the cars was tagged “Salonika”

Rumours of the arrival of Greek Jews spread like lightning. Among the arrivals were intellectuals, people of high station, a few professors and university lecturers. While they had come all this way in freight cars, the strangest thing to us, that the cars had not been locked and sealed.

Everyone was well dressed and carried lots of baggage. Amazed we eyed marvellous oriental carpets, we couldn’t take our eyes off the enormous reserve of food. We began salivating as we stared at bags loaded with delicacies, fruits and drinks.

Besides food, these Jews took along a reserve of clothing various and sundry accessories, trinkets. They all disembarked from the freight cars in perfect order and serenity. Attractive well –dressed women, children as pretty as dolls, gentlemen tidying up their lapels.

Miete found three German speaking Greeks and appointed them translators, they moved about with armbands embellished with the Greek colours. Not a single one grasped where he was and what his fate was to be. The truth only penetrated when they were being led naked, supposedly to the baths, and suddenly the first blows fall.”

Since October 1942 the chairman of the Jewish Council had been Rabbi Koretz who, because the Germans had kept in some months in Vienna had a taint of collaboration.

Consequently, on 17 March 1943 when he made a speech in the Monasteriotes Synagogue, extolling the new life in Poland, he was so ill-received as to require police protection. Yet in spite of the distrust of Koretz there was practically no resistance to the deportations.

It was believed that the emigrants would be better off than the labour conscripts, some of whom got married in order to be included in the deportation trains for the “Krakow ghetto.”

The Germans used many subterfuges. Some witnesses who survived Auschwitz have claimed they were shown grants of land in the Ukraine, which were bought by Salonika Jews into the death camp.

Furthermore Mme. Vaillant – Couturier has described the fictitious picture- postcards of a place called Waldsee, by which Jewesses from Salonika were made to invite their relatives to join them.

Another subterfuge is mentioned by Dr. Albert Menasche, Dr Merten assured Rabbi Koretz that the deportations were no more than a security measure to remove potential communists from the military zone. They would not affect the middle classes. Thus 900 intellectuals and people of means were kept in “Baron Hirsch” camp after the departure of the Organisation Todt workers.

They were then told a different story – as privileged Jews they would be sent to the “Free Ghetto” Theresienstadt. In fact the train, which carried 880 of them away on 1 June 1943 went to Auschwitz. This transport arrived in Auschwitz on 8 June 1943 and after a selection 220 men and 88 women are admitted into the camp. The other 572 deportees are murdered in the gas chambers.

Those who survived the war from the Salonika deportations to Auschwitz, Treblinka and Majdanek can almost be numbered on one’s fingers.

The journey alone lasted several days, crowded together in poorly ventilated box-cars, many of the Jews commenced the journey in poor-health, but the Salonika Jews brought to Auschwitz spotted typhus, which was the worst epidemic imaginable.

Birkenau was quarantined during June 1943 and during September and October 1943 all the Salonika Jews were liquidated. It was not possible to fill more than two Auschwitz transports with Jews from Athens, so effectively were they hidden in this great city.

A few hundred were detected after the first registration, and there were also some hundreds in privileged categories who left Athens for Bergen- Belsen on 2 April 1944.

The Athens deportees reached Auschwitz in better shape than the Salonika deportees. On 21 August 1944 a secret camp radio transmission mentioned 1838 Greek Jews surviving in Birkenau.

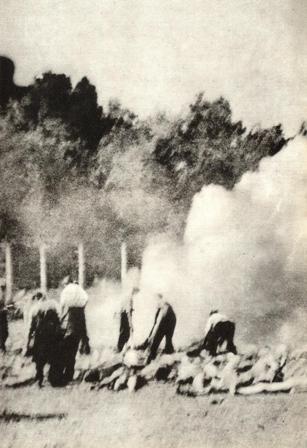

This figure included 300 of the April deportees who had been selected for work in the Sonderkommando which served the gas chambers and crematoria.

All these men including some well-known members of the Salonika intelligentsia, worked the death factory during the deportations from Hungary, Lodz and the Krakow region and died in the mutinies at the crematoria on 7 October 1944.

A Greek Jew working at Crematoria ll, wrote shortly before the revolt of the Sonderkommando, “to take a revenge for the death of my father, my mother, my beloved sister Nella.”

More than three hundred Greek Jews were among the Sonderkommando preparing for the uprising, among them Errera de Larissa, a former lieutenant in the Greek army.

The three photographs taken in Birkenau in the summer of 1944 were probably taken clandestinely by Alex, a Greek Jew, who was a member of the Sonderkommando:

Armando Aaron from Corfu recalled the arrest and journey to Auschwitz:

“On Friday morning 9 June 1944 members of the Corfu Jewish Community came, very frightened, and reported to the Germans.

The square was full of Gestapo men and police and we went forward. There were even traitors, the Recanati brothers, Athens Jews, after the war they were sentenced to life imprisonment.

There were 1650 people, after we gathered here, Gestapo men with machine guns came up behind us. It was six o’clock in the morning. The day was fine.

We were arrested here on 9 June and we finally arrived in Auschwitz on 29 June. Most were burned on the night of the twenty-ninth. We stayed in Corfu for five days in the fort. No one dared escape and leave his father, mother, brothers. Our solidarity was on religious and family grounds. The first group left on 11 June 1944. I went with the second convoy on 15 June.

We were on a boat called a zattera – that’s a boat made of barrels and planks. It was towed by a small boat with Germans in it. On our boat there were not many Germans, but we were terrified. You can understand, terror is the best of guards.

The journey was terrible, no water, nothing to eat, ninety in cars that were good for only twenty animals, all of us standing up. A lot of us died. Later they put the dead in another car, in quicklime. They burned them in Auschwitz too.”

On 16 August 1944 the last transport from Greece reached Birkenau – it contained the entire Jewish population of the island of Rhodes, some 2500 people. In June 1944 Lieut- General Kliemann, the commander of the Rhodes garrison, received a visit by two SS- officers, presumably members of Eichmann’s office.

Immediately afterwards, he posted notices ordering all Jews to reside in a particular group of villages from which they were transferred to some military barracks.

Then came the order of “Ost- Agais Command” that they should be off the island by 17 July 1944, but the action was postponed to the beginning of August, when the Jews were embarked in some old caiques, and these set sail for the Greek mainland.

346 men and 254 women were selected from the Rhodes transport to work in the camp the remainder were killed in the gas chambers. Whilst impossible to be precise, it would appear that about 10,000 Greek Jews survived the holocaust from the 1931 census figure of 67,200.

Sources:

The Final Solution by G. Reitlinger – Vallentine Mitchell &Co Ltd 1953 Auschwitz Chronicle by Danuta Czech published by Henry Holt New York 1989 Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka by Yitzhak Arad published by Indiana University Press – Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987 The Holocaust – The Jewish Tragedy by Sir Martin Gilbert published by Collins London 1986 Auschwitz – A History in Photographs – published byPanstwowe Muzeum Oswiecim- Brezinka 1990 Shoah – by Claude Lanzmann – published by Pantheon Books New York 1985 USHMM

Copyright 2007 Mark Symonatis H.E.A.R.T

|