The Germans invaded Denmark on 9 April 1940, in a combined

attack against Norway, a few hours later the Danish

Government accepted the German ultimatum and surrendered.

At the beginning of 1942 Himmler and Heydrich enlisted the

zealous aid of the Foreign Office to get the Nuremberg

anti-Jewish laws applied to all Western countries under

military occupation.

In Holland, a totally occupied

country this pressure could not be resisted, in France a

half-occupied country, it was half-resisted. In the case of

Denmark a nation which retained its neutrality under German

occupation, with a monarchy and constitution both

unimpaired.

Here the pressure of Ribbentrop and

Himmler was resisted with ninety-five per cent success –

almost the only bright spark in a truly dark and depressing

tale of murder and misery.

In January 1942 it was

reported in the American press that the King of Denmark had

threatened to abdicate if the German demand for Nuremberg

legislation was pressed.

As a consequence, Rademacher

the SS watch-dog over the Diplomatic Corps, advised Cecil

von Renthe- Fink, the Reich plenipotentiary in Copenhagen,

“to find occasions to point out that it would be prudent for

Denmark to prepare in good time for the Final Solution.”

But Denmark was not prudent, and in June 1942, when the

Germans were pressing for a Danish “Jewish badge” decree,

similar to which had been in force in the Reich since

September 1941, King Christian was reported to have said

that he would be the first Danish citizen to wear the badge.

Himmler now tried to proceed against the Jews in Denmark in

the guise of security measures. On 24 September 1942 he

ordered Heinrich Muller, the head of the Gestapo, to insert

the names of Jews in a list of Danish Communist and

resistance leaders whom he proposed to arrest.

No

doubt Himmler believed he could rely on the co-operation of

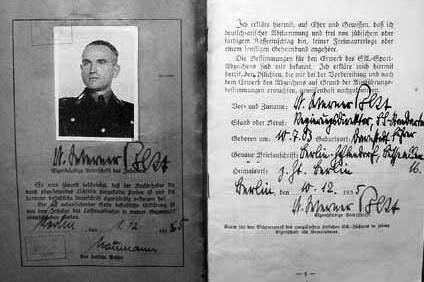

Renthe-Fink successor, Karl Werner Best, since Best had once

been legal advisor to the Gestapo – but Best who had left

the Gestapo to escape the clutches of Heydrich, was now

relieved of the worst anxieties of a successful careerist by

the death of his enemy.

Moreover, as a Reich

plenipotentiary in a quasi-neutral country, Best desired a

quiet life above all things, so his report to Ribbentrop on

28 January 1943, was quite daring. Best suggested that,

since the proposed measures would certainly create a

constitutional crisis in Denmark, the Danes should be asked

only to dismiss their Jews from the civil service.

Under Himmler’s prodding Ribbentrop returned to the charge,

and on 24 April, Best replied that out of 6,500 Jews in

Denmark only 31 were civil servants. Of course, there were

the 1,351 refugees from the Reich whom the Danish Government

had hitherto protected, but Best suggested that the Danes

would not be able to do this any longer if the refugees were

given back their German nationality.

Such a step was,

however, impossible under the 11th decree supplementing the

Reich Law of Citizenship, which could not be retracted in

the case of refugees in Denmark without upsetting the whole

legal fabric of the deportations from Germany.

Himmler still insisted on the full application of the Final

Solution in Denmark and Ribbentrop as usual, gave way. On 22

May he informed Best that while he could not take

instructions from Himmler, the next steps might be discussed

with Himmler in the precincts of the Foreign Office, if

necessary in Ribbentrop’s presence.

Nothing however was done till August when a disturbance in

Denmark gave Himmler the pretext he required. On 5 August

1943, Sweden renounced the 1940 agreement by which German

troops stationed in Norway were permitted to use her railway

system.

This action inspired the Danish dock workers

at Odense to refuse to repair German ships. There were riots

and arrests and on 9 August, the Danish Premier Scavenius,

threatened to resign if the Danish courts were required to

try the arrested men.

As a consequence, the Germans

introduced martial law at Odense, and on the 24 August 1943

– the day that Himmler was made Minister of Interior – the

Danish resistance movement blew up the German – occupied

Forum Hall in Copenhagen, and on the following day all the

Danish shipyards were on strike.

On the 28th the

Scavenius Government resigned, on the 29th General von

Hannecken, the German military commander, proclaimed martial

law throughout Denmark. The Danish defence forces were

interned, while the small Danish fleet either scuttled

itself or sought internment in Swedish ports.

But even now Best and von Hannecken could not take over the

government of Denmark, since they had to rely on a Committee

of Ministerial Directors to act for the absent Danish

Cabinet.

It appeared to Best, nevertheless, that this

provided the opportunity for deportations, and on 8

September 1943 he asked for police reinforcements and help

from the German Army, “so that the Jewish problem can be

handled during the present siege conditions and not later.”

But as a witness at the War Crimes trial in Nuremberg on 31

July 1946, Best tried to put the cart before the horse, he

claimed that he had only approved of martial law for Denmark

after Himmler had fixed the date for the deportations,

which, he feared would cause riots.

At the same time

he warned certain Danish politicians of Himmler’s plans, yet

according to his report to von Ribbenentrop, Best had made

it clear to the Danish Foreign Office that the arrest of

Jewish notables ”had nothing to do with the Jewish

question.”

The truth would seem to be that Best, in

company with von Hannecken and even the Security Police

chiefs in Denmark was seized at the last moment with a fear

of the world publicity which the action ordered by Himmler

would inevitably follow.

On 18 September Rolf Gunther

arrived in Copenhagen from Berlin, with a special commando

of members of Eichmann’s office. The station commander of

the Security Police in Copenhagen, Standartenfuhrer Rudolf

Mildner, at once perceived what matters would be charged to

his responsibility and flew to Berlin to get Kaltenbrunner

to withdraw the commando, but without success.

Best in the meantime, continued to cover himself either way.

Thus on the night of the round-up, he promised Ministerial

Director Svennigsen of the Danish Foreign Office to forward

the King’s petition that the Jews should be interned in

Denmark.

But Best had already tried to interest

Ribbentrop in a far less honorable proposal, proceeding from

Helmer Rostig , a former League of Nations Commissioner in

Danzig, now head of the Danish Red Cross.

This was

that the Jews should be interned in place of the Danish

soldiers, “to show that Germany was at war not with the

Danes, but with the Jews,” and that fifty to hundred Jews

should thereafter be deported for each Danish act of

sabotage.

Furthermore, on 28 September Best assured von Ribbentrop

that the deportations would start as soon as the steamer

Wartheland berthed in Copenhagen, and he complained that

through the non-co-operation of von Hannecken, the Security

Police were unable to proceed with the round-up in Jutland

and Fuenen.

Von Hannecken had in fact been engaged in an intrigue to

shift the responsibility on to Best’s shoulders. He had

asked Keitel on the 23rd to suspend the round-up during the

period in which the German Army was responsible for

maintaining order, if indeed, it was not possible to cancel

altogether such unpopular measures, which would mean “the

loss of Danish meat and fats.”

Keitel replied that Gottlob Berger, Himmler’s chief of

personnel would be in charge of the “aktion.” Von Hannecken

thereupon refused to lend the Security Police the use of his

Feldgendarmarie and Secret Field Police – a direct challenge

to Keitel and the High Command.

On 29 September Ribbentrop telegraphed Best that he had read

his complaint to Hitler in the presence of Keitel, who

denied that he had banned the use of Wehrmacht police, and

swore that he would demand an explanation from Hannecken.

But the latter told the Danish Commission in 1945 that, even

after the rocket he got from Keitel, he only provided fifty

men of a guard battalion to cordon the embarkation on board

the Wartheland.

At the Nuremberg War Crimes Trial, Colonel – General Alfred

Jodl, chief of the operations section of the High Command,

insisted that these fifty men must have been policemen. He

had telephoned von Hannecken to have nothing to do with the

deportation order, which was Himmler’s affair.

This

got back to Best via Colonel von Engelmann of the Abwehr

which was the German equivalent of MI 5. Best then

telegraphed Ribbentrop on the eve of the deportation action

“that Keitel’s order for co-operation had been revoked, and

that Keitel had misinformed the Fuhrer.”

One is to gather from al this that, except for those who

were conveniently dead like Himmler, no German carried out

the Fuhrer’s order in Denmark. In reality, the misgivings of

Germans in office played less part in saving the Jews than

the unique geographical position of Denmark, separated by a

bare ten miles of sea from the neutral Government of Sweden,

the only Government to offer unconditional asylum to an

entire Jewish population which was threatened by the Final

Solution.

But in October 1943, the Ministers of

neutral countries had less reason to be susceptible to the

German mailed fist than, for instance, the Swiss Ministry of

Justice and Police, which had refused to admit Jewish

refugees from the terror in France precisely a year earlier.

Geography and the changed way of neutrality did not however

explain everything. No rescue would have been possible if

the bulk of the Danish nation had not been sympathetic and a

very large number of ordinary people disposed to risk their

lives out of common charity.

The figures are eloquent, only 284 Jews were arrested on the

night of 1 October, of whom 50 were released and only 202

embarked in the Wartheland. They were mostly people who were

too old to hide from the police. Casual arrests in the next

few days brought the number to 477, but more than 6,000 full

Jews and 1,376 half-Jews were smuggled into Sweden in

fishing boats between 26 September and 12 October 1943.

On the morning after the round-up, Best suggested that the

interned Danish soldiers should be released at once to show

that the “Danish peasant boys” were not being treated like

Jews. Von Hannecken at the same time demanded the

abandonment of martial law.

It suited Himmler to

believe that Denmark was now “Jew –Free” and both requests

were soon granted. Best was less successful in trying to get

some of the Danish Jews out of the clutches of Eichmann’s

office. He believed that it might appease Danish public

opinion if a Jewess, aged 102, could be brought back from

Theresienstadt together with a few other very old people.

On this project von Thadden, the successor to Luther and

Rademacher , reported back to his chief Wagner, on 25

October that the RSHA thoroughly disapproved, because it

would create an impression of weakness among the Jews, if

any were brought back to Copenhagen.

In the meantime,

the Foreign Office maintained unreal negotiations with the

Swedish Government. Unofficially, the Danish Jewish refugees

were in Sweden enjoying complete liberty.

Officially they were still in hiding in Denmark and the

Swedish Government offered to intern them if the Germans

would hand them over. On 4 October the Swedish Minister in

Berlin begged that Sweden might at least be allowed to take

the children.

Weizsacker was no longer von

Ribbentrop’s First Secretary of State – since his transfer

to the Vatican, his place had been taken by Adolf

Steengracht von Moyland , who formally refused the offer,

upbraiding the Swedish Minister in Berlin in terms which he

recalled as follows:

“In very severe words I

criticized today’s Swedish morning press and told him that I

was unable to imagine what further reactions might be

possible in Sweden after the newspapers had voiced such

incredible language.

If the occasion arose, this attitude would force us to

answer in a manner not to be misunderstood. It was not

appreciated here why Sweden was unequivocally taking the

side of Bolshevism, while our blood and the blood of our

allies was being expended to keep the Communist danger from

Europe and thus also from the Nordic countries.”

It had been decided early in September that the Danish Jews

should go to Theresienstadt not Auschwitz. About 360 were

sent via the port of Swinemunde, and of these twenty died on

the journey and fifty in the camp.

Werner Best was

sentenced to death by a Copenhagen court in August 1946,

soon after his appearance as a witness at the Nuremberg War

Crimes Trial.

His appeal was not heard by the High Court till 20 July

1949, when in the light of new evidence, his sentence was

reduced to five years imprisonment. He was released on 29

August 1951.

Sources:

The Final Solution by G. Reitlinger –

Vallentine Mitchell &Co Ltd 1953 .

Beretning fra

Centralkontoret for s rlige Anliggender for Stork benhavn,

1946

PRO UK