The destruction of the Jews of Italy The Italian Government surrendered its forces to the Allies on 8 September 1943, and on the following day General Mark Clark launched Operation Avalanche, the landing of Allied troops on the coast of Italy, near Salerno.

On the 10 September 1943 the Germans occupied Rome, Mussolini’s officials perhaps guided by Mussolini himself tried to substitute half-measures to thwart deportation to the gas chambers in the death camps in the east.

But after his captivity on the Gran Sasso, Mussolini was a deflated balloon, and the Italian government was much weakened, the Gestapo wasted no time, aided by the Jewish registration lists created in the days when Mussolini and his fascist government had issued anti-Jewish decrees.

It was most unfortunate that many of the native and refugee Jews who made their way south following the Allied forces landings in Calabria should have waited in Rome, when the Germans occupied the city on the 10 September 1943 about 8,000 Jews fell into German hands, a sixth of the Jewish population of Italy.

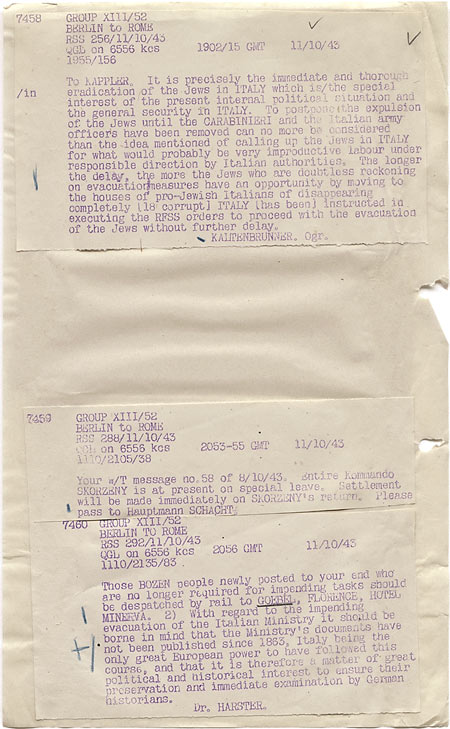

By the end of September 1943 it was known to the German Embassies in Rome and the Vatican City that Himmler intended to send these Jews to the Auschwitz – Birkenau death camp. On the 30 September Bishop Hudal, rector of the German church in Rome warned General Stahel, the Town Commandant, that the Pope might take a position against the deportations.

Stahel decided not to carry out the deportations without the permission of the Foreign Office, at the same time Mollhausen, the German Consul-General in Rome, wrote personally to Ribbentrop, recommending internment in Italian labour camps rather than deportation.

The response could have been predicted, Ribbentrop would not intervene with the SD, from whom Stahel took his orders – the first round-up of Jews in Rome occurred on 18 October 1943.

The always compliant Baron Ernst von Weizsacker was now very much on the spot as Ambassador to the Holy See. Much was made at Weizsacker trial of the warnings which he gave both to the Vatican and the Jewish community leaders of the impending action.

The only certain intervention of von Weizsacker is the forwarding of Bishop Hudal’s protest to the Security Police commander, Obersturmbannfuhrer Hubert Kappler. But that was only on 22 October 1943 after the round-up had already taken place.

According to Gerhard Gumpert, Weizsacker’s First Secretary, Kappler was persuaded that Hudal’s warning to Stahel had been inspired by the Pope. Kappler was now too frightened to continue the actions.

This version of events does not ring true firstly because Kappler did inh fact continue the round-ups, and secondly because the action of 18 October had taken place without the least protest from the Vatican. The best witness is Weizsacker himself, writing to Dr Karl Ritter, Minister for Special Purposes at the Foreign Office in Berlin:

“Although pressed on all sides, the Pope did not allow himself to be drawn into any demonstration of reproof at the deportation of the Jews of Rome. The only sign of disapproval was a veiled allusion in Osservatore Romano on 25-28 October, in which only a restricted number of people could recognise a reference to the Jewish question.” Pope Pius Xll negative attitude towards the Jews, he never renounced the 1933 concordant with Hitler and who only denounced the National Socialist regime, only after the German surrender in spring 1945. However, there can be no doubt regarding the sympathy and practical assistance of the clergy in Rome, monasteries and convents sheltered a very large portion of the Jews who were warned in time and who went into hiding.

Nevertheless, on the night of 18 October 1943 1,270 Jews were arrested of whom 235 had to be released. On 23 October 1,035 Jewish men, women and children arrived at Auschwitz- Birkenau, and 839 people were murdered in the gas chambers.

Until 4 June 1944 when the Allied forces liberated Rome the Germans continued to deport Jews in small batches, approximately a quarter of Rome’s Jews were deported while the rest spent eight haunted months in hiding.

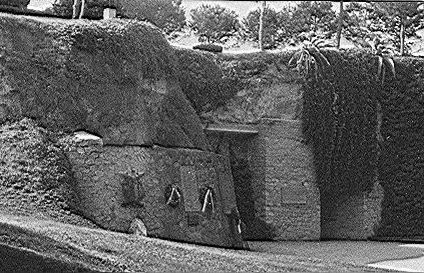

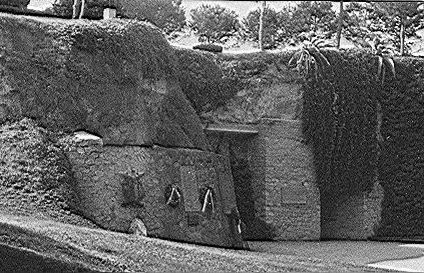

Adreatina Caves where 335 were murdered |

Only 102 Jews of the 2091 deportees survived the war, another 75 victims were murdered on 24 March 1944 in the Adreatina Tunnel, for which SS – Hauptstumfuhrer Erich Preibke who had fled to Argentina after the war had ended, but was extradited to Italy to stand trial. He was at first tried and released. Then on a re-trial, he was found guilty of war crimes and sentenced to serve fifteen years in prison on 14 April 1997.

On 23 March a bomb was thrown at a company of German Security Police marching along the Via Rasella. On learning that 32 of them had died, Hitler ordered the death of ten Italians for each German.

The order was conveyed through Field-Marshall Kesselring, General von Mackensen of the 14th Army, and General Malzer, Town Commandant of Rome. Finally, it was passed to the executioner, the same Obersturmbannfuhrer Kappler, who was responsible for the mass round-up of Jews in October 1943.

The 335 victims were shot under Kappler’s eyes in the Ardeatina Tunnel, they included people whom the Italian fascist police had selected at random, plus 75 Jews whom Kappler had thrown in as a matter of course.

As soon as the armistice was announced in September 1943 a police commando of the SS left Novara for Lake Maggiore, arresting numerous Jews in Licino, Stresa, Baveno, and Pallanza. These Jews disappeared completely, but a number of bodies were said to be recovered by fishermen from the lake.

Incidents like this were common but, after a few weeks, casual murder was replaced by methodical destruction, early in October 1943, Martin Sandberger, a former Einsatzgruppen commander in Russia, took over the Gestapo in Mussolini’s capital Verona, while Theo Dannecker, who had been Eichmann’s representative in Paris and Sofia, became Jewish Commissary for Italy.

The task which confronted Sandberger and Dannecker was complicated by the dispersed nature of the Jewish population in Italy, but a bonus was the availability of a number of empty prisoner of war camps north of the Apennines. The German Army had succeeded in removing the British prisoners, who were held by the Italians, at a time when Badoglio’s dealings with the Allies were still in doubt.

Under the Fascist Republic, the SD filled these camps with the Italian opposition, the Yugoslav partisans and any Jews they could find, all being destined for deportation to the Reich.

There was however, a time-lag between the Rome deportation of 18 October 1943 and the deportations from the North Italian camps, which did not begin until February 1944, a law of the Italian Fascist Republic was announced on 1 December 1943, ordering the committal of all Jews to concentration camps. About a fifth of the Jews living in Italy, partly refugees from abroad and partly the remains of the native community who had not gone underground or emigrated, were rounded up during the twenty months of the Fascist Republic.

The number of names of Jewish deportees, received by the Search Committee for Deported Jews, is 10,271, of whom some 2824 were sent to Auschwitz in 1944 from a single collecting centre, the camp at Fossoli di Carpi near Modena. Since this was classed as a mere transit camp, families were not broken up nor the sexes segregated.

Although it was handed over to the SD after the Badoglio armistice, the administration stayed in Italian hands and was relatively mild. According to Primo Levi, who survived Auschwitz, it was even possible to get drunk.

The Jews were sent to Auschwitz whenever the camp, which contained other categories of internees, became too full. 650 Jews, some of them from Tripoli, left on 22 February 1944 arriving in the Auschwitz – Birkenau death camp on 26 February, following the usual selection 526 people were killed in the gas chambers.

Primo Levi who was in this transport recalled in his memoirs:

“With the absurd precision to which we later had to accustom ourselves, the Germans held the roll call. At the end the officer asked “Wieviel Stuck?” (How many pieces?) The corporal saluted smartly and replied that there were “six hundred and fifty pieces and that all was in order.”

Then they loaded us on to the buses and took us to the station of Carpi. Here the train was waiting for us, with our escort for the journey. Here we received the first blows – and it was so new and senseless that we felt no pain, neither in body nor in spirit. Only a profound amazement – how can one hit a man without anger?

There were twelve goods wagons for six hundred and fifty men – in mine we were only forty-five, but it was a small wagon. Here then, before our very eyes, under our very feet, was one of those notorious transport trains, those which never return, and of which, shuddering and a little incredulous, we had so often heard speak.

Exactly like this, detail for detail – goods wagons closed from the outside, with men, women and children pressed together without pity, like cheap merchandise, for a journey down there towards the bottom. This time it is us who are inside.

The doors had been closed at once, but the train did not move until evening. We had learnt of our destination with relief, Auschwitz- a name without significance for us at the time, but it at least implied some place on this earth.

The train traveled slowly, with long unnerving halts. Through the slit, we saw the tall pale cliffs of the Adige Valley and the names of the last Italian cities disappear behind us. We passed the Brenner at midday of the second day and everyone stood up, but no one said a word.

The thought of the return journey stuck in my heart and I cruelly pictured to myself the inhuman joy of that other journey, with doors open, no one wanting to flee, and the first Italian names….. and I looked around and wondered how many, among that poor human dust, would be struck by fate. Among the forty-five people in my wagon only four saw their homes again, and it was by far the most fortunate wagon.

We suffered from thirst and cold – at every stop we clamored for water, or even a handful of snow, but we were rarely heard – the soldiers of the escort drove off everybody who tried to approach the convoy. Two young mothers, nursing their children, groaned night and day, begging for water. Our state of nervous tension made the hunger, exhaustion and lack of sleep less of a torment. But the hours of darkness were nightmares without end.

Our restless sleep was often interrupted by noisy and futile disputes, by curses, by kicks and blows blindly delivered to ward off some encroachment and inevitable contact. Then someone would light a candle, and its mournful flicker would reveal an obscure agitation, a human mass, extended across the floor, confused and continuous, sluggish and aching, rising here and there in sudden convulsions and immediately collapsing again in exhaustion. Through the slit, known and unknown names of Austrian cities, Salzburg, Vienna, then Czech, finally Polish names. On the evening of the fourth day the cold became intense – the train ran through interminable black pine forests, climbing perceptibly. The snow was high.

It must have been a branch line as the stations were small and almost deserted, during the halts, no one tried any more to communicate with the outside world – we felt ourselves by now “on the other side.”

"There was a long halt in open country – the train started up with extreme slowness, and the convoy stopped for the last time, in the dead of night, in the middle of a dark and silent plain. That dark and silent plain was Auschwitz."

On 30 June 1944 another transport from Fossoli di Carpi nearly 1,000 Jews arrived in Auschwitz – Birkenau, from which 582 Jews are murdered in the gas chambers,

The transport from Fossoli di Carpi which conveyed 300 Jews to Auschwitz –Birkenau was the final transport from that camp, as the Allied forces were approaching the Gothic Line, and the province of Modena had become a combat zone.

The chief transit camp was now Gries near Bolzano, 180 miles closer to Vienna and Auschwitz. From Gries a final small transport reached Auschwitz-Birkenau on 28 October 1944, a few days before gassing was halted in early November.

Most of the Gries transports went to Mauthausen concentration camp, where the rate of human destruction was just as dreadful as Auschwitz. On 25 February 1945, a transport of 150 Jews returned to the Gries Sammellager, because the Mauthausen train was blocked by a successful Allied bombing raid on the Brenner Pass.

One has to compare the results of this unintentional air attack on a strongly defended Brenner Pass with the Allies decision not to bomb the railway lines heading to Auschwitz- Birkenau, were relatively undefended, how many thousands of Jews perished, as a result of this strategy. About 5000 Jews were shipped to Auschwitz and the Reich from other Italian towns and transit camps, a collective transport from Rome, Trieste and Fiume reached Auschwitz in December 1943, and 132 Jews were sent from Trieste. This particular transport arrived on the 4 April 1944, and 103 Jews were killed in the gas chambers.

The case of Trieste was unusual since, as a former Austrian city, it was incorporated into the Reich on 23 September 1943, as the capital of a new Gau, Trieste – Kustenland. Friedrich Rainer was appointed Gauleiter and his friend from the Austrian Anschluss days of 1938, Odilo Globocnik, was appointed as Higher SS and Police Leader by Himmler.

Odilo Globocnik, who was born in Trieste on 21 April 1904, and he brought with him to Trieste a number of SS and Police members who had served under him as part of Aktion Reinhard, the mass murder programme of Polish Jews.

Before the war there were more than 5,000 Jews in Trieste, but less than half remained behind when the Germans occupied Trieste. There was a round-up on the 9 October 1943 and a second on the 19 January 1944, when Dr Morpurgo, secretary of the Community Council, was taken, and the old-peoples home, “Pia Casa Gentilomo” was liquidated.

The 70 inmates from the old-peoples home were kept for seven days in the rice warehouses at San Sabba before being shipped to Auschwitz, where they arrive in the camp on 2 February 1944. The buildings of Riseria di San Sabba, in the outskirts of Trieste were constructed in 1913 and had been vacant for years, when the Germans took them over. The warehouses were first used as a prison -however, in October 1943 the complex was converted into a Polizeihaftlager – (police detention camp).

The premises were ideal for this purpose, three high buildings which included cells, storage rooms, dressmaking and shoe-making workshops and living quarters for the SS and police staff.

The tall old chimney, in combination with an enlarged old oven was used for cremating thousands of victims a small gas chamber was built in the courtyard. The installations were made ready under the supervision of Erwin Lambert, the “flying architect” of T4 and Aktion Reinhard, who supervised the improved gas chambers at Treblinka and Sobibor.

The crematorium was tested on 4 April 1944 with the burning of seventy corpses, from 20 October 1943 until early 1945 approximately 25,000 partisans and Jews were interrogated and tortured at San Sabba, between 3,000 to 5,000 of them were killed, either by shooting, beating or in the gas chamber.

SS – Sturmbannfuhrer Christian Wirth was the camp commandant until he was killed by partisans on 26 May 1944, he was replaced by SS-Obersturmbannfuhrer Dieter Allers who remained as camp commandant until the dissolution of the camp in April 1945.

In late April 1945 as Yugoslav partisans prepared to liberate Trieste, on 29 April 1945 the Germans blew up the crematorium in order to destroy the evidence of their crimes.

The camp staff fled the camp and went into hiding, hoping to escape justice, there was no trial for the crimes committed at San Sabba.

Returning to the history of Trieste on the 25 January 1944 Globocnik dissolved the Community Council and closed the synagogue, and thereafter the Jews of Trieste led an underground life.

On the 30 April 1944 23 Jewish men and women who enjoyed Swiss consular protection arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau, they were deported because a bomb had exploded in a German officer’s mess in the Via Gegha.

During the whole period of the German occupation, some 600 Trieste Jews were deported to the death camps and only 400 -500 living in great destitution were discovered after the entry of the 8th Army on 7 May 1945.

Sources: The Final Solution by G. Reitlinger – Vallentine Mitchell &Co Ltd 1953. Auschwitz Chronicle – by Danuta Czech, published by Henry Holt and Company – New York, 1989. Holocaust Journey – by Sir Martin Gilbert, published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1997. Belzec Death Camp – by Michael Tregenza – The Wiener Library Bulletin 1977. Holocaust Historical Society. The Jewish Museum of Deportation and Resistance Copyright Chris Webb &

Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T 2008 |