Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Occupation German Occupation of Europe Timeline

-

[The Occupied Nations]

Poland Austria Belgium Bulgaria Denmark France Germany Greece Hungary Italy Luxembourg The Netherlands Norway Romania Slovakia Soviet Union Sudetenland | ||||||||

POLISH FORT-NIGHTLY REVIEW London, Tuesday, May 1 1945 Issue No. 115 Polish Women in German Concentration Camps

Foreword

A wave of indignation is passing over the world today as the result of the revelation of the conditions in which the prisoners in German concentration camps have lived and died.

Unfortunately, not even the most horrible of these revelations is new to Poles, for they know the German concentration camp methods only too well, the deaths of thousands of people from “heart attacks” in one day as the result of an injection of phenol, and the unfailing ingenuity of German everyday brutality.

The Press has already given horrible details of the concentration camp at Buchenwald. In this camp, as in all German camps, there were also Polish prisoners. Out of some 50,000 Polish prisoners held there until recently, the Allied troops have managed to release only 3,500 altogether; the others have either been carried off from the camp by the Germans, or have died.

And yet as Florian Sokolow, a correspondent of the Polish Telegraph Agency, reports in his message from Buchenwald on April 21st, the conditions of existence in this camp were comparatively much better than those in the great camps in Poland: in Oswiecim or Majdanek.

This is what he writes:

“For that matter, Buchenwald is not among the worst of the concentration camps. It was a camp of slow death by exhaustion, sickness and hunger. The number of those put to death there by various kinds of torture is 51,000, a comparatively small proportion of the total number of Buchenwald’s victims.

A former prisoner in Oswiecim (Auschwitz in German nomenclature), Sokolow, goes on, “whom I met there, told me that by comparison with Oswiecim, Buchenwald was a paradise.”

This view is confirmed in the Parliamentary Deputation Report on Buchenwald as quoted in “The Times” on April 28th:

“One of the statements made to us most frequently by prisoners was that conditions in other camps, particularly those in Eastern Europe, were far worse than at Buchenwald.

The worst camp of all was said by many to be at Auschwitz; these men all insisted on showing us their Auschwitz camp numbers, tattooed in blue on their left forearms.”

In this number of the POLISH FORTNIGHTLY REVIEW we give two extensive reports on the conditions of existence in the women’s concentration camp at Brzezinka (Birkenau in German nomenclature) as well as a shorter note on the medical experiments made on women in the same camp.

This camp was close to the notorious camp at Oswiecim, in south –eastern Poland, and was in fact part of it. All the stories are from eyewitnesses, women and girls who were imprisoned in Brzezinka, and they have reached Polish official circles in London by devious routes.

They relate to the second half of 1943 and the beginning of 1944.

The camp at Brzezinka was one of the three main concentration camps for Polish women. The others were that at Majdanek, near Lublin, and at Ravensbruck. At the moment of writing this second camp is still in German – held territory.

AN EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT OF THE WOMEN’S CAMP AT OSWIECIM – BRZEZINKA (Birkenau)

Autumn 1943, to Spring 1944

At the outset I want to say that the details given below are strictly true and authentic. They are not dictated by any desire for propaganda, by hatred, or love of exaggeration.

On the contrary, instead of making the picture more glaring, I shall try to tone it down, to make it more credible. For the reality I have to write about is so horrible that it is difficult to expect that anyone who hasn’t seen it should believe it. Yet it is the reality. Please believe this short account of that reality, and believe my words as you would believe someone returned from the dead.

The women’s concentration camp at Oswiecim has officially no connection whatever with the men’s camp. They are two separate worlds. The data concerning either of them do not apply to the other.

Founded a year or more after the men’s camp had been started, the women’s camp is at present passing through that same process of successive horrors which the men’s camp has already experienced. The results are still more terrible, for women have less powers of resistance and are more helpless than men.

Some Figures

The serial number of the women at present in the camp runs into the eighty thousands. Of this number, 65,000 women of various nationalities have died during the past two years.

The majority of the deaths have been Jewesses, but several other nations have contributed large quotas. The total number of Polish women who have passed through the camp is reckoned at fifteen to sixteen thousand. Of these 5,500 are still alive, the others are dead. The number of released women are insignificant, and do not amount to one percent of the total.

The women’s camp is an abyss of misery, a horrible slaughter house for thousands upon thousands of women. Their ages range from ten to seventy. The crimes for which they are incarcerated are equally varied: in addition to serious political cases, and women soldiers captured with arms in hand, there is a Poznan woman who refused to sell her favourite cat to a German woman.

Her hard bed is shared by a twelve- year old girl who, while collecting her father’s geese, happened unknowingly to cross the frontier, so-called near Czestochowa. She has been here for two years as a serious political criminal.

The nationalities are just as varied: Polish, Russian, Ukrainian, Yugoslavian, German, French and Jewish. The Jewesses are the most numerous and most unfortunate of all. At first the conditions at Brzezinka were so horrible that very few of those who came to the camp in the early days are still alive. A great transport of a thousand women brought from the Fordon prison two years ago, is recalled by only four women still alive.

There are very few low serial numbers left in Brzezinka, and they are very rare. When one listens to the stories of those still left one is seized with indescribable horror. Although there has been a great improvement in conditions since then, the mortality continues to be enormous. For instance, out of a number of prisoners transferred from the Pawiak prison in Warsaw on October 5th, two- thirds have died.

In the winter the women are decimated by typhus, in the summer by malaria. All through the year bad hygienic conditions, starvation and a horrible ruthless, humiliating regime prevail.

Conditions of Work

Seven hundred Polish women work in the camp itself, in the kitchen, the laundry, the tailoring department, the packing department, the clothing warehouse, the office etc. They are all privileged individuals, for they work with a roof over their head and in moderate temperature.

All the others with the exception of five hundred at present “parked” in hospital go to work out of doors. This work is compulsory winter and summer. Frost, rain, snow, heat, nothing holds up the march of the columns to work in the fields. Only when there is a dense mist are they kept in barracks, for fear they should escape.

This is the only rest they have, as Sunday is not observed. The work assigned to the women is very hard. In the winter the rivers Vistula and Sola were cleaned up, and the women digging out the channels stood up to their knees in water all day. Another group carried stones and paving for roads. Heavy artillery wagons, no longer in service since the army was motorised, and so transferred by the Wehrmacht to the camps, were hauled along by the women.

The work lasts twelve hours each day, it should not be forgotten that the workers are inadequately clothed, have no outdoor clothes, and go winter and summer in the same clothing which they wear in the barracks, and are undernourished into the bargain.

Food

The food at Brzezinka is terrible: a quarter kilogramme of bread each day, five dekagram’s of margarine or sausage, a decoction of leaves and herbs morning and evening (un-sweetened), soup made of turnips in the afternoon.

Never of anything else but turnips and prepared in a specially repulsive fashion. It is really horrible, and after it the soup given in other prisons seems tasty. It has no fat or any other positive elements, and is completely valueless.

Such food is not sufficient for a day’s work and so it is only the food parcels which keep the women alive and only ten per cent of them receive parcels.

Distinguishing Marks

On arrival at the camp every woman is at once tattooed with her number on the left forearm. The shaving of the head, which was compulsory until recently, has been stopped.

Then all her clothes are taken and all articles in exchange for the striped camp uniform. The number is repeated on the clothes, striped with the addition of a triangle and a letter indicating the women’s nationality.

A red triangle indicated political “criminals,” a green one thieves and a black one anti-social behaviour i.e. sabotage and prostitution. The Jewesses are given stars. They do not wear the striped garment, but ragged civilian clothing, with a great red cross painted with oil paint between the shoulders.

They are not entitled to receive parcels or write letters. It is worth mentioning here that the Jewesses given numbers amount to some ten percent, of the total number of Jewish women brought to Brzezinka. Of the transports of Jews which arrive every day from all over Europe, ten percent of each group go to the camp, are given numbers, and live out their lives in a barrack, to perish successively in the monthly selections.

The other ninety percent go straight from the railway to the gas chamber and the crematorium. They suffer a briefer torment. How many there have been of these condemned it is impossible to calculate. The ten percent mentioned above numbered a total of almost forty thousand.

The Camp Authorities

Birkenau is divided into Camp A and Camp B. The camp commandant is the notorious murderer and executioner Tauber. That name must not be forgotten, he has on his conscience the lives of many thousand women.

Just as notorious are the Ober Drexler and her assistant Hasse. These are the lowest dregs. Under them are two “camp seniors,” (Lageralteste). In Camp A she is “Bubi” the former president of a Lesbian club in Berlin. In Camp B she is “Stenia” a very cruel woman with sadistic instincts.

The immediate authority over the prisoners is the “block,” she may be a German, a Polish woman, a Czech, a Yugoslavian. In general they are bad types, though among them are some outstanding women.

It depends on them whether the life of a prisoner is tolerable or not, for they can even make for a certain alleviation of the prisoner’s lot. The other categories of officials the “capos,” work supervisors are the same as in the men’s camp.

The Camp

The camp covers an enormous area. It is adjacent to the gypsy concentration camp, in which there are swarms of gypsies, who like the Jews have been brought here from all parts of Europe. At the moment they are not being slaughtered, but the mortality among them is very high. They have no rights and are not allowed to go to hospital.

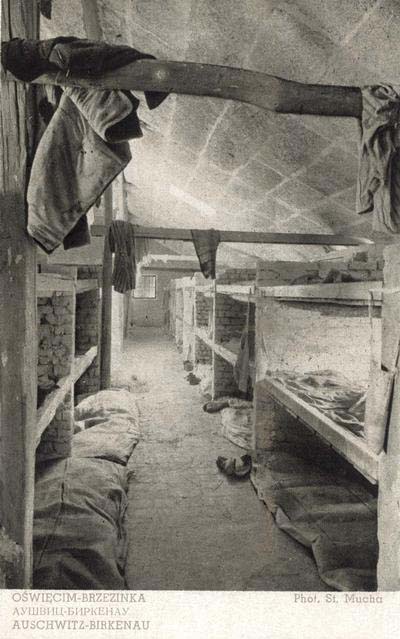

Within the bounds of Brzezinka there are six chimneys or crematoria which are always in use and belch smoke all day, and flame at night. The living barracks or “blocks” are of two kinds, the old ones are of brick and the new ones of wood. It is warmer in the brick barracks in the winter time, but instead of beds they have the notorious bunks which hold up to eight persons.

In these suffocating lairs sometimes twelve to fourteen women have to lie, in the summertime that is an indescribable torture. The wooden barracks are better, for instead of the bunks they have three- tiered beds, but on the other hand it is as cold inside these barracks as outside.

The sanitary arrangements are a nightmare of camp life. A permanent defect of the camp is the repeated and chronic shortage of water. There have been times when the prisoners could not wash themselves for weeks or even months. The camp is surrounded by a trench and by wire, which is said to be charged with high tension current. Said to be, because in fact the current is rarely switched on owing to the necessity for economy.

So that this fact may not come to light, the guards in the guard-houses are ordered to shoot anyone who goes anywhere near the wire. They may not allow a suicide to approach the barrier. Only recently the guard had a day off as reward for killing a prisoner.

The ground at Brzezinka is miry and clayey, the women’s camp which covers an area of well over a thousand acres, is built on a swamp on saturated clayey leas. The camp had previously been the scene of the terrible death of several tens of thousands of Soviet prisoners of war, who were killed by starvation.

These unhappy wretches chewed the grass and had to resort to cannibalism, their bodies were sucked down into the swamp and they had no other form of burial. Then the miry soil which constituted one enormous grave, was covered over with rubble and the barracks built on it.

Streets were marked out and Brzezinka came into being, in addition to the normal malaria which had been chronic in the district for many years, innumerable infections caused by the decay of human bodies buried only just under the surface spread in the area.

And as there is no other water in Brzezinka except that lying above the subsoil, one can imagine the sanitary conditions which prevail. All over the camp not a blade of green is to be seen, nothing ever grows on the clayey earth, which is trampled over by thousands of feet. There is too much tears and blood in this soil for it to produce anything.

Only rats and mice multiply on it. The lice became a plague of the camp for there was no way of escaping them, they were everywhere. After the last typhus epidemic, which carried off Germans too, energetic steps were taken to delouse the camp and there was a decided reduction in the number of lice.

There remained the other plague of rats, they were innumerable and loathsome, they gnaw at the corpses waiting to be taken to the crematorium, they attack the sick and deprive the healthy of all possibility of sleep. The railway station of Oswiecim lies just over a mile from Brzezinka, a sideline has recently been built over which the trains loaded with prisoners run right into the camp through the wire.

The Hospital

A large part of the camp is occupied by the “park” as the hospital is called. It consists of over a dozen barracks. This hospital, unique in its kind, calls for extensive description separately.

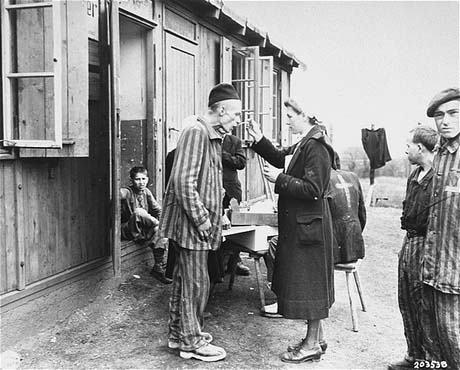

It is distinguished by its primitive and anti-hygienic conditions and the complete absence of medicaments. There are doctors, the majority of them Polish women, who work with incredible devotion and self-sacrifice, but their labour and good will are not of much benefit, for they haven’t even the simplest and most essential of medical supplies.

Last winter, during a terrible typhus epidemic – there is a typhus epidemic every year – the “park” became a scene of moving tragedy. The sick were crowded in it so much that the feverish half-delirious women lay four to each narrow bed.

About 300 women died every day – some 9,000 monthly, the bodies were dragged out of the block and flung in a heap, like piles of wood. A heap of these emaciated, distorted bodies with wide open eyes and mouths lay in front of every hospital building.

Before the lorries arrived each evening to remove this daily contribution and take it to the crematorium the bodies were gnawed by rats of which there are numberless multitudes in the camp, and pecked by the rooks.

At this period when the head doctor, a German, came to inspect the blocks, he paid not the least attention to the piles of bodies, or to the doctor’s requests for medicines, but closely examined the walls to see if there was any dust or spider’s webs anywhere.

And if he noticed anything of this kind he talked threateningly about the necessity to observe hygienic conditions. But why raise the question of medical supplies, for that matter, when there was even a lack of water in the hospital and the sick died of thirst?

In the February the typhus epidemic died away by itself, having carried off over twenty thousand victims. The mortality in the camp has dropped for the time being, but an outbreak of ordinary summer malaria is expected soon, and that will continue till September. The only preventative against malaria is quinine, but there is none whatever in the camp.

The Prisoners Powers of Endurance

Oswiecim takes its greatest toll of life among the youngest of its inmates. Proportionally girls up to the age of twenty have the greatest mortality rate (and there is a huge number of such girls in the camp), together with women over fifty.

The middle- ages best survive the long starvation and hard labour, members of the intellectual classes die more rapidly than those of the working class. Among the nationalities of which so many are represented at Brzezinka, the French women proved to have the lowest powers of resistance (there are only 26 of them alive in the camp, and at one time they numbered several hundred), while the Russians and Yugoslavians are the strongest and have the greatest powers of endurance.

Among the more outstanding women who died in the camp last winter was the wife of General Mikhailovich, the Commander – in – Chief in Yugoslavia, and among the Polish women were Maria Sadowska (Stronska), Natalia Hiszpanska, Zofia Kraczkiewicz, Lucia Charewiczowa (docent of Lwow University) and the painter Jewniewiczowa.

Deaths last year included Emilia Grocholska, the well-known publicist, Zarzycka, the writer and the grey-haired poetess Savitri (Anna Zahorska), who was left to die outside a block, after being beaten up with sticks.

Escapes

Many minds are occupied with the thought of possible escape. There are frequent escapes from the men’s camp, and eighty percent of them are successful. Up to a hundred escapes each month, and last January, when mists were especially common, some 160 prisoners got away.

Almost every day while a roll call is being held, the sirens begin to wail to announce that someone’s escape has been discovered. At the sound patrols composed of capos, guards and others go off to seek the prisoners.

They do not appear to be very fervent in their searches. On the other hand, escapes from the women’s camp are very rare, and only a few cases are known to have occurred.

Degradation

Are the starvation and everyday torments of life as we have described it the worst side of a stay in Brzezinka? Does the horror of the camp system depend on them?

There are still worse things, the horror derives from the complete denial and destruction of humanity. Once a prisoner has arrived at the camp, she ceases to be a human being; she is only a number, an animal, and less than an animal.

Everything will rather be forgiven her than any display of human dignity, of shame, of noble indignation. The Germans carry through their programme of dehumanization, of humiliation and subjection with incomparable consequentiality and with the systematic order peculiar to that nation.

Despite their stupidity the Germans have realised that the nature of the women determines the nature of the nation. To destroy the woman is to destroy the morrow of their hated neighbours.

So the few who do not die must go back home mutilated, feminine modesty is a powerful moral factor, it is equivalent to the conception of feminine virtue. So let modesty and honour perish. This is the purpose of the mass compulsion on the prisoners to strip themselves bare and to march naked past Germans.

And so a line of beautiful naked girls, naked pregnant mothers, naked old and exhausted women walks along. They are scarlet with shame. An SS man calls out jeeringly: “Forward the political ladies! Forward!”

The tears pour down the faces of some of the girls and fall on their bare breasts. A gang of men from the men’s camp is working mending the road along which the procession marches. Their naked wives, sisters, mothers pass them by only a few paces away.

And something fine and moving happens: without a word of command, all the men turn and stand with their backs to the road. Not one of them moves, or turns his head until the women have passed. Like the old story of Lady Godiva.

The procession reaches the bath, called “Sauna” and the water of the showers washes away the tears. A group of SS men come up and watch the bathing women, looking for volunteers for “Puf,” the brothel. At present women can apply voluntarily, but if there are no volunteers, the SS men would select their victims.

A crowd of naked girls from Lowicz district huddles in terror in one corner like an anxious frightened herd. But a German woman, a former cabaret singer, breaks away from the larger crowd, and proudly displays her still not entirely ravaged body while she sings pornographic German songs.

Encouraged by her example another, a withered gypsy starts out and begins to dance a fiery Cossack dance. She is lissom, her bare thighs swing round, she drops to a squatting position to kick out her legs, the two dry pieces of skin which were once breasts smack together. The SS men laugh aloud in their amusement and lash at the dancer with their whips when she halts breathless. The Lowicz girls weep aloud.

Part of the system of dehumanizing the prisoners consists in compelling them to perform even the most intimate physiological necessities in public. There is no chance of isolation in the camp, and a moment of solitude is an empty dream.

The woman slave is always one of an animal herd, always surrounded by a crowd, incessantly hunted, cuffed, heaped with the most horrible expressions. This slave, a living number, does not possess a change of under-linen, cannot call the least thing her own, and has an unchallenged right to only one thing: to death, and the inhabitants of the camp avail themselves abundantly of that right.

Like Slaves in Ancient Egypt

Rain falls very often in Oswiecim, the district has the heaviest rainfall in Poland. Through the slanting streams of cold autumn rain one sees a long row of great, heavy ex-artillery wagons loaded with rubble or rubbish, moving along a “Lagerstrasse.”

These wagons are drawn by undernourished, emaciated women in striped overalls. Twenty pull at the shafts and traces, sixteen – eight on each side – turn the spokes of the wheels with the movement known to the world from the slaves depicted on Egyptian bas-reliefs.

They work like that all day, wet through. Their miserable clothing, made from wood-pulp, is soaked through in an instant. On the other hand it takes long to dry out. When after the roll-call the labourers return to their barracks they are glad to throw off their wet rags, and to wrap themselves in dry blankets.

But the clothing does not get dry during the night, and when they have to get up at daybreak next morning they draw on a wet overall, put on soaking wet boots. They will shiver with the cold until the kindly sun has pity on them, warming and drying them.

But suppose the downpour lasts several days!

When the gleam of the sunset shines on the accursed high-tension wires surrounding the camp, when the evening roll-call brings all the inhabitants of the camp without exception together, the mortally weary columns of women workers move up from all directions. Some of them are carrying burdens on stretchers.

Others haven’t stretchers, so they drag their burdens along the ground….. what are those burdens? The dead bodies of their comrades who have died at work that day. Sometimes one or two, sometimes more. The stretchers are short. The legs and arms hang stiffly, helplessly.

A band playing a lively march comes out to meet them, involuntarily the slaves’ weary legs fall into step, the rhythm is communicated to the dead, and the hanging hands, the helpless feet begin to keep time.

Death in Oswiecim

In November last year the annual typhus broke out in Brzezinka. It was especially violent in its course. In November, December and January the deaths amounted to nine thousand per month. Three hundred women a day.

The hospital blocks were overcrowded, four sick women lay on each narrow pallet, try to imagine the picture of four women in a high fever, pressed close together, unable to stir, with bodies covered all over with the itch and ulcers, eaten alive with lice and fleas.

There could be no thought of fighting the epidemic, for there were no medical supplies, they did not exist at all, not even the simplest and most primitive. Nothing. And of what avail was the devotion and good-will of the doctors (most of them Polish women) when all they could do was to certify the disease and had nothing which to treat it.

And so the sick died , died without religious consolation- without a friendly word of farewell. Young girls died for whom their mothers were waiting yearningly at home, mothers died for whom little children were waiting at home. Some departed with resignation, others clung desperately to life, “I cant die, I promised mother I’d come back for certain,” one dying girl complained.

The block personnel carried out the bodies and flung them down in the yard outside the doors, by evening a large pile of bodies was gathered, lying in the mud or snow, naked yellow and blue, fearfully emaciated, arms flung out, flung down carelessly, legs straddled with staring eyes. For death in Oswiecim, the death which is the comrade of every prisoner, is entirely lacking in piety, beauty and respect. It is as ugly as if Satan himself, the lord of the camp, was playing with humanity and its after-death hopes.

The bodies lay in the yard all day, for the lorry carrying them to the crematorium came only in the evening. All this time the rats rummaged among them. But once it happened that the rats gnawed at the forearm of a dead woman and destroyed the number there tattooed, the only proof of her identity, and owing to the bureaucratic complications this caused, the camp authorities ordered that the lorry was to come twice a day, so as not to leave so much time the rats.

The epidemic was at its height at Christmas time. A huge fir tree hung about with electric lamps shining brilliantly stood in the “Lagerstrasse.” The light picked out the pile of dead bodies, but the merry sounds of music came from the “Sauna.”

The local band was giving a concert - the death-wires rang with the frost, as though this sound had a suggestive power, more than one desperate woman made her way towards it that night. The guard in various parts of the camp opened fire again and again. The “posts” sitting in their towers were firing, for they were not allowed a suicide get near the wire. They had to shoot her first.

A year ago a “post” got a week’s leave for shooting a prisoner, they were lucky, every time they wanted to visit their girls, they watched for a woman prisoner getting too close to the wire, and their leave was assured.

The Jews

Health and strength, honour and life – it is not sufficient to deprive the prisoners of these in order to consummate the work of dehumanizing them: the prisoners must be robbed of their heart. Perhaps the greatest torment of a stay in the camp was the sight of the terrible tragedy of the Jews which was open to all the camp to see. In Brzezinka there were six chimneys or crematoria, they were never idle.

Not an evening passes without the prisoners seeing the flames leaping out of the broad chimneys, sometimes to a height of thirty feet, not a day passes without heavy billows of smoke pouring from them.

The cremating of the bodies of these who die in the camp is only a small part of the crematoria’s functions. They are intended for the living rather than the dead. And every day trains draw into the camp along the sideline, bringing Jews from Bulgaria, Greece, Rumania, Hungary, Italy, Germany, Holland, Belgium, France, Poland and until recently from Russia.

The trains bring men, women and children, and old people. Ten percent of the women in each train are sent to the camp, are given a number tattooed on them, a star on their clothing and the numbers of those in the camp are thus increased.

The others are sent straight to the gas chamber, the scenes which take place there defy all powers of description. But as ten percent of the transports brought to the camp amount to over thirty thousand Jewish women, what is the total figure of the victims whom the crematoria have consumed?

It is terrible to think, terrible to watch when lorries pass through the Lagerstrasse carrying four thousand children under ten years of age – children from the ghetto in Terezin in Bohemia – to their death. Some of them were weeping and calling, “Mummy,” others were laughing at the passers by and waving their hands.

Fifteen minutes later not one of them was left alive, and the gas – stupefied little bodies were burning in the horrible furnaces. But who will believe that this is true? Yet I swear that it was so, calling on the living and the dead as my witness.

Stupefied by gas…. Yes, for gas was dear, and the “special command – Sonderkommando servicing the death chamber, used it very economically. The amount of gas used kills the weaker organisms, but only sends the stronger organisms to sleep for a little while. The latter revive on the crematoria lorries and are flung alive into the roaring fires.

The fact that they are transferred to the camp and given a number does not save the ten percent of Jewish women from death: it only postpones death. Every month a “sorting” or selection goes on in the camp. Irrespective of the weather and time of year all the Jewish women have to report naked at the roll-call. The camp authorities examine them and assign a certain proportion to the “chimneys.”

Who can say what governs the decision as “to the choice?” They select not only old, sick women, but young girls with healthy handsome bodies. As the selection takes some days, those condemned do not go straight to the “chimneys,” but remain for the time being locked up in the notorious “Block No 25.”

There they await their fate, naked and despairing. They get nothing more to eat and drink after that. And so through the grated windows comes a terrible howl of despair, an imploring wail: “Water, water for God’s sake, water! If you believe in Christ, give us water!”

But anyone who gives them water, or even approaches a window is in danger of death herself. Even so, there were Polish women who did not hesitate to give the condemned water or snow at night. This heroism was rather of service in demonstrating to themselves that they were still human, for what did a few buckets of water mean to a thousand condemned?

The despairing wail, the wail of dying animals, did not cease for several days and nights in the summer. It rent the heart, until at last silence fell. Lorries drove up and executioners went into the death block. They seized each woman in turn by arms and legs, swung the bodies and flung them on to the lorry. The heads crashed hollowly against the floor or side. When full the lorry set off to take its terrible load to the chamber.

I am writing the truth, the very truth that I have seen all this time with my own eyes, and that even so it is only a small part of what I have seen. I pass over in silence a number of no less horrible facts: the misery of the mothers, the “regulation” killing of newly-born babies, the sombre “Block 10,” in which women are subjected to horrible and murderous experiments as though they were rabbits, the weekly selection of Aryan women in the hospital, compulsory until recently, etc.

If I wanted to tell everything, I should never finish"

REPORT MADE BY A GIRL FIFTEEN YEARS OLD

The concentration camp for women at Oswiecim is really at Brzezinka (Birkenau) not far from Oswiecim, but the address for both men and women is the same: “Auschwitz Konzentrationslager.”

The men and women’s camps at Brzezinka are newer, and are much worse than the men’s camp at Oswiecim, because of the lack of organisation.

The women’s camp occupied a large area, and consists of thirty blocks – or barracks – both brick and timber. The locality is unhealthy, swampy. The camp is surrounded by wire charged with high-tension electric current. The men’s camps have two rows of this type of fencing.

Guards huts are placed at intervals along the wire, the guards are equipped with both ordinary and hand-machine guns. Similar huts are scattered quite thickly about the area outside, for a distance of several kilometres from the camp. The blocks inside the camp consist of barracks for living accommodation, hospitals, warehouses for storing the prisoners’ belongings, baths, tailors’ shop and kitchen.

Of the living barracks, one is set aside as a punitive block – No. 25 and one for better conditions- No.12. This last barrack is occupied by office workers (political officials), workers in the warehouses and members of the camp band.

A normal block contains from 800 to 1,000 and more women. Such a block is a very long barrack; in it are three rows (lengthways), of three –tiered bunks, or rather compartments. On each compartment sleep from five to eight people, each compartment is three times as broad as a prison bed.

The bedding consists of straw palliasses and two blankets for three persons. It depends on ones ingenuity whether one gets more blankets. Most of the prisoners sleep in their clothes. All they possess, e.g. packets of food, and small personal belongings, is stored under the palliasse, in a hole of the roof etc.

The barrack has many windows in the walls and roof, in the winter there are two iron stoves for the entire barrack, buckets for the usual purposes stand in the yard outside the barrack. One is allowed to go out to them at night.

In Block No 12 each person has her own bed, sheet, blankets and the block is clean. Accommodation is better than usual in the punitive block, for there is more room, but the block is completely isolated from all the others and one cannot have any contact with others, which is quite easy in the case of prisoners in other blocks.

Inhabitants of Block No.12 do not go outside the camp to work, but do particularly hard work inside, such as digging trenches, carrying soil without regard to the weather.

A commandant is in charge of the camp with German wardresses in uniform under him. They guard the camp area inside and take the roll-calls. The guards huts are serviced by men – many of them Ukrainians. In addition there are “posts” consisting of youngsters in Gestapo uniform, who supervise work in the fields – these are not to be feared.

There are also men in charge of various sectors, known as commands, who are specialists on the work which they supervise. In addition to these German authorities there are the minor authorities drawn from the women prisoners themselves.

One is the senior in the camp, and under her are the block supervisors, known as “blocks,” who are in general authority over the particular barrack, with the added privilege of being allowed to beat their charges, which they are fond of doing.

Under these are the “stubes” who are responsible for sections of the block, the “block” has her own room attached to the barrack, the “stubes” sleep with the other prisoners.

There are also women prisoners who supervise during labour, these usually being German criminals. The “stubes” wake up the prisoners at about 4a.m. at five a.m. there is coffee, and at 5.30 the prisoners go outside the block for roll-call, which is at six a.m.

After it there is the march to work, dinner is taken at the place of work from twelve to two o’clock. Work ends at five o’clock, there is the march back to the camp, and at six o’clock the roll-call and supper.

After the supper the prisoners are left to themselves until nine p.m. – after which there must be silence - and the lights in the barracks are turned off. The entire area of the camp is brilliantly lit up all night

Most of the prisoners work in the open, the weaker go to collect medical herbs, work in the tailor’s shop and twist ropes. Most of them are older women. The doctor decides whether a prisoner is to be assigned lighter work. The food each day is: morning only coffee, dinner tinned soup or with margarine; supper, coffee, two hundred grams of bread with jam or margarine, or something similar.

Twice a week each prisoner gets half a loaf of bread additional. Food parcels can be received even every day – they arrive unbroken. Bread and food constitute the currency with which one can buy anything, from warm clothing to the regards of the “block” or even hospital nurse. It is a fundamental condition of survival that the prisoner must have a large quantity of food sent to the camp.

The parcels may contain soap, tooth-powder, tooth-brushes, toilet paper, but no clothing, prisoners may write once a month and receive letters several times a month. Prisoners are sent to the hospital on developing a temperature of 38 degrees C, but the prisoners are afraid of the hospital owing to the ease with which infectious diseases can be picked up there.

A separate barrack for infectious diseases has now been established, there are an average of two thousand sick in a camp of twelve thousand. Half of them are infectious, with typhus, typhoid and dysentery. Almost all who have been any time in the camp have had all these.

Formally the daily mortality was 200, but now it averages fifteen to fifty, the hospital is overcrowded with three patients on each bed. A German doctor is in charge, but under him are some thirty women doctors, prisoners of various nationalities.

Owing to the in-sanitary and un-hygienic conditions the camp is dirty and lousy, there is nowhere to wash and nothing to wash with. There is a bath and change of clothes once a month, a new washing place has now been made, and maybe things are better.

When a transport of prisoners arrives it goes to the transit barracks. There political women officials – themselves prisoners – take down personal details and tattoo numbers on their arms (it is not very painful) then others shave all heads (this is done only once, and afterwards one may grow one’s hair).

They collect all the clothing, see the prisoners through the baths and issue camp clothing: a shirt, drawers, an overall, an apron, kerchief, socks or stockings, boots and foot-wraps. One can keep one’s own house slippers, but all others are taken. The clothing issue in the winter is the same, plus a ragged cowl and a cotton kerchief.

The new arrivals when dressed are placed in a quarantine block, whence, however, they go out to normal work the next day, after three weeks they are transferred to the permanent blocks.

The Jewesses have a special mark on their arms, the German women are not tattooed or shaved, the prisoners have triangular badges on their arms: red to indicate political prisoners, green for criminal prisoners, black for prostitutes. Jewesses have badges sewn on their chest. All the types of work have special clothing.

In the winter the women work exactly like the men, they pull down houses, uproot tree stumps, shift snow – all useless work, the only reason for it is to tire out the prisoner. Every day several women frozen to death are brought in.

The morning and evening roll-calls last several hours, and are held in the frost outside the barrack, the sick were carried out to the roll-call and it was forbidden to cover them with anything. (The hospital has no roll-call whatever now.) There were no separate hospital blocks whatever, and the sick lay together with the well. Hospital blocks were organised only in February – March.

Now things are still better, for three branches have been organised in the hospital; for light illnesses and inflammation of the lungs, typhus and dysentery – formerly they were all kept together.

There were no closets whatever in the winter, one had to relieve oneself beyond and between the blocks, this together with the swampy ground created an un-crossable mire of filth, which the prisoners were ordered to clean up with their bare hands, without any implements.

There was no water whatever, water was brought from Oswiecim for the soup and coffee, there was no means of washing at all. The dirt and lice were appalling. From time to time a general roll-call was held and this meant standing for several hours, sometimes up to twenty in the frost.

And then every tenth woman or women picked at a glance, or through caprice, or those who were not strong enough to run at full speed to the block after the roll-call, were transferred to the punitive block, at that time this simply meant a wait of a few days before transfer to the gas chamber. Such roll-calls were quite frequent.

At that time every fifth man was taken, one night at 2a.m. a roll-call was held to be spent on the knees and it lasted till nine a.m. It was held outside the block in the frozen filth.

Now the roll-call lasts an hour at the most. In the winter the average daily mortality is between two and three hundred. Of prisoners brought to the camp some time ago only an average of ten to twenty percent remained alive.

Recent transports of prisoners have a relatively low mortality, the majority of the deaths are Jewesses, or Greek women, who cannot stand the climate. Apart from this almost all the prisoners suffer from dysentery, probably owing to the complete non-observance of cleanliness.

MEDICAL EXPERIMENTS

Report on Block 10 in Women’s Camp at Oswiecim – Brzezinka

For nearly twelve months – the writer is reporting in March 1944 – block number 10 has been set apart for experiments. It holds about 450 women who are the patients of Professor Schumann, Professor Glansbeg*, Doctor’s Wirt** and Weber.

The first experiments were made by Professor Schuman on young girls aged between fifteen and eighteen, the experiments consisted of sterilization by light and later operations for the incision of ovaries were performed.

In recent months no new operations have been performed, the last operations were performed three months ago on ten girls who were previously given the light treatment. One of the patients died immediately, probably from internal haemorrhage, owing to a faulty operation. Of the other nine, two are still seriously ill and the others still have to lie in bed.

At the moment Professor Glansberg has 175 women patients, one cannot say for certain what he is doing to them. All that is known is that he injects a fluid, which he alone knows the nature of, into the womb, in order to fill the ovary ducts, then he takes Roentgen photographs.

It is probable that he is testing a new method of taking Roentgen ray photographs of the womb and ovary ducts, which in general is not injurious to the health. These operations are repeated again and again (four to five times) on the same women at different periods of time.

Glansberg detains the women on whom he is making these experiments, and sees that no other experiments are made on them. It is not known what intentions he has for them in the future. He performs all the operations himself with the assistance of untrained personnel, who have no idea what he is doing.

Some four months ago Dr Samuel carried out an operation on the instruction of Dr Wirths; incision of the mucous membrane at the entrance of the womb. This is intended as part of a series of investigations into early diagnosis of cancer. The operation itself is a light one, with no lasting ill-effects.

But it frequently leads to later flooding as the result of a clumsy operation. Dr Samuel adopted a rapid tempo in operating (three or more a day) which was not at all required by him. The operated patients were sent by the next transport to Brzezinka.

These experiments have been discontinued for the past four months. In order to keep his post Dr Samuel torments a large number of women with daily gynaecological investigation and photography (ceroscopy).

The Hygiene Laboratory No. 1 has established the blood groups of almost all the women and have taken blood samples from those suitable. The blood served for the preparation of test serum, necessary in establishing the blood group.

Blood samples have been taken from 150 women in six months. The quantity averaged 100 to 150 cm. These women receive additional soup and one additional ration of bread and sausage.

Other experiments are now being made: the saliva is being examined in order to establish an element in the blood group. This is being done by Dr Munch. It consists of a subcutaneous injection of diluted streptococcal toxin, which is aimed at proving whether there is any inflammatory centre in the organism. These experiments are innocent enough.

At present the following experiments are continuing:

(a) Professor Glansberg’s injections (b) Dr Samuels colcoscopy (c) The Hygiene Laboratory’s experiments

From the scientific aspect these experiments are senseless, but they affect the women’s state of health, namely:

Notes

* Professor Glansberg is probably Professor Carl Clauberg ** Dr Wirt is probably Dr Eduard Wirths

Short Biography of Medical Personnel Named in Above Report

Professor Dr Carl Clauberg – Reserve SS Major General – was born in 1898 into an artisan family in Wupperhof, Germany. An infantryman in World War One, he later studied medicine and advanced to head doctor at the women’s university clinic in Kiel.

In 1933 he joined the Nazi Party and was quickly considered a fanatical representative of its Weltanschauung. The same year he was appointed professor of gynaecology at the University of Konigsberg.

In 1942 he approached Heinrich Himmler, Reichsfuhrer – SS who was already interested in Clauberg’s research and he asked Himmler for an opportunity to perform sterilization experiments on a broad scale.

In December 1942 Clauberg came to Auschwitz and in April 1943 obtained Block 10 for his experiments. Looking for a “cheap and efficient method” of making women sterile, he injected corrosive liquid into the uterus without using anaesthesia.

Clauberg fled from the advancing Red Army to Ravensbruck concentration camp where he continued his experiments, it is estimated that he conducted sterilization experiments on about 700 women.

In 1948 he was tried in the Soviet Union and sentenced to twenty-five years in prison, however, he was freed in an amnesty in 1955 and returned to Kiel, boasting of his “scientific achievements.”

Only after the Central Council of Jews denounced him was he arrested in November 1955, he died in 1957 shortly before his trial was due to commence.

Horst Schumann M.D – First Lieutenant of the Luftwaffe and SS Major – was born in 1906, the son of a general practitioner in Halle on the Saale. A member of the Nazi Party since 1930 and in the SA since 1932, Schumann received his medical degree in Halle in 1933 and was employed in the health office in Halle in 1934.

When the Second World War began in 1939 he was conscripted as a subordinate physician in the Luftwaffe. Summonsed in 1935 by Viktor Brack, department head of Operation T4, to participate in the euthanasia programme as a doctor, Schumann accepted.

In January 1940 he became director of the Euthanasia Institute of Grafeneck in Wurttemberg, where people were killed by engine exhaust. In the summer of 1940 he became director of the Sonnenstein Institute near Pirna.

As a member of the secret operation known as 14f-13 Schumann belonged to a committee of doctors who selected prisoners in Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Dachau, Flossenburg, Gross Rosen, Mauthausen, Neuengamme and Neiderhangen, who were especially weak and incapable of working, and who were subsequently taken to euthanasia institutes and gassed.

On the 28 July 1941 Schumann went to Auschwitz for the first time where he selected 575 prisoners to be taken to Sonnenstein where they were put to death by gassing.

On the 2 November 1942 he returned to Auschwitz to test a “cheap and rapid” mass sterilization method for both men and women using x-rays. He carried out his experiments on young healthy good looking Jewish men, women and girls whom he chose himself.

Hardly any of his numerous victims survived, the people died from burns, from additional surgical procedures, exhaustion or psychic shock.

In 1944 before he left Auschwitz he reported to Heinrich Himmler that “castration of men in this way is pretty much ruled out, or an expense is required that is not worthwhile.”

In October 1945 he surfaced in Gladbeck, where he registered with the police and was made municipal sport physician. With a refugee grant he opened his own practice in 1949 and did not attract the attention of the authorities as a wanted Nazi criminal until 1951.

Since 21 days elapsed between his identification and the attempt to arrest him – and in addition he was probably warned by the Gladbeck municipal physician’s council – Schumann had already escaped when the police showed up at his house.

According to his own account in subsequent years he served as a ship’s doctor and worked in the Sudan after 1955, escaping from there in 1959 through Nigeria and Libya to Ghana.

Not until 1966, after the fall of Nkrumah did Ghana extradite Schumann to West Germany, and four years later the trial against Schumann began, but due to his poor health it was stopped a year later.

Schumann died on the 5 May 1983

Eduard Wirths, M.D. – SS First Lieutenant was born in Wurzburg in 1909, he came from a Catholic family associated with Democratic Socialism and worked as a rural doctor after he completed his medical studies.

In 1933 he joined the Nazi Party and the SA, and he undertook official health related assignments as well as maintaining his practice. He became a member of the Waffen-SS in 1939 and served with troops in Norway and the Soviet Union. Because of a heart ailment he was designated unfit for front-line service in April 1942 and was sent briefly to the Dachau and Neuengamme concentration camps, and in September 1942 was sent to Auschwitz camp as Garrison Doctor.

All SS Camp doctors were subordinate to him; he deployed them on the selection platform according to a hierarchical principle – he himself regularly participated in selections – so as to cultivate the discipline and self-image of his subordinates.

Wirths himself was subordinate to Office D-III for Sanitation and Camp Hygiene in the WVHA in Berlin, which was directed after 1942 by the physician Enno Lolling. But he was also subordinate to the Commandant of Auschwitz with whom he dealt daily.

It was Wirths who, within the camp hierarchy, insisted that an order from Berlin be followed that only doctors should carry out selections. Hence Wirths had not only control over selections, he organised the system.

Wirths “scientific experiments” were aimed at the early detection of cervical cancer, he himself never appeared personally at the experiments, which were frequently fatal to the subjects.

In 1945 Wirths was arrested by the British Army and committed suicide.

Sources:

The National Archives KEW The Chris Webb Archive Yad Vashem Public Records Office, London Polish Museum in the United Kingdom Holocaust Historical Society Auschwitz Chronicle 1939 -1945 by Danuta Czech, published by Henry Holt and Company New York 1990 US NARA USHMM

Copyright Chris Webb H.E.A.R.T 2011

|