Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Occupation German Occupation of Europe Timeline

-

[The Occupied Nations]

Poland Austria Belgium Bulgaria Denmark France Germany Greece Hungary Italy Luxembourg The Netherlands Norway Romania Slovakia Soviet Union Sudetenland | |||||||

The Hlinka Guard Paramilitary Arm of the Slovak HSSP

The holocaust began for the Slovka Jews in Autumn of 1938, when Slovakia became an autonomous region. Upon conclusion of the first Vienna award on on 2 November 1938, a percentage of southern Slovakia and the town of Kosice were ceded to Hungary.

Of course this action elicited outrage against Slovak nationalists who took it upon themselves to proclaim that "Magyar Jews" were the cause of this loss of Slovak territory.

Over the next three years Slovak Jews became subject to constant harassment, and their freedom of movement was restricted in a series of legislative actions promulgated by the Zidovsky kodex or "Jewish Code" enacted on September 9 1941. The code was comprised of 270 articles, which contained all previous Jewish restrictions, and host of new orders as well.

Jewish property was confiscated and businesses liquidated at bargain prices all in an effort to "Aryanize" the country. In the Autumn of 1941 Slovak leaders approached Heinrich Himmler for assistance in ridding themselves of their Jewish population completely. An arrangement was then made with the German Reich in January, 1942, where the Slovak government agreed to pay the equivalent of 500 Reichsmark for every Jew the Germans removed.

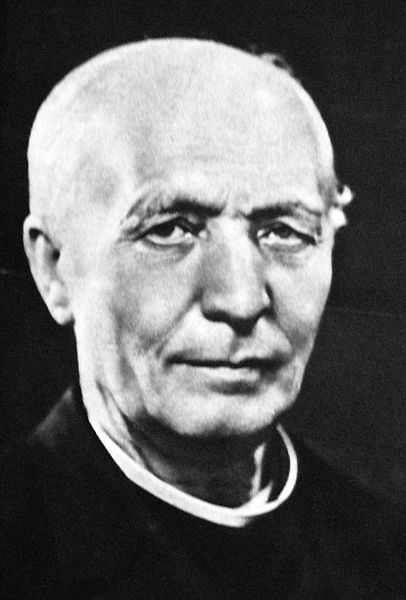

The Hilinka Guard was the paramilitary unit created by Catholic Priest Andrej Hlinka and controlled by the Slovak People's Party or HSSP. The Guard was officially established on October 8, 1938 but its roots cab be traced back as early as the 1920's to the "Rodobrana" a strong arm group that styled itself along the lines of the Mussolini's' Black shirts, and the Nazi SA.

The HSSP being a Catholic religious group in its orientation found its support among Slovak Catholics. The Slovak peasantry had suffered hardships during the period of economic readjustment after the disintegration of the Hapsburg Empire. Moreover, the apparent lack of qualified Slovaks had led to the importation of Czechs into Slovakia to fill jobs in administration, education, and the judiciary.

Although Andrej Hlinka's objective was solely Slovak autonomy within a democratic Czechoslovak state, his party contained a more radical wing, led by Vojtech Tuka. From the early 1920s, Tuka maintained secret contacts with Austria, Hungary, and Hitler's NSDAP.

It was Tuka who formed the Rodobrana and began publishing subversive and anti-Semitic literature. Tuka later gained the support of the younger members of the Slovak Populist Party, who called themselves Nastupists, after the journal Nastup.

The Rodobrana and its offshoot the Hlinka Guard are said to have represented the major factions of Slovak fascism. Although it is believed that the Hlinka Guard may have actually been less violent that their cousins in the SA/SS, or Romanian "Iron Guard", there is no doubt as to their level of involvement and culpability in the looting of Jewish property, the beatings and forced deportation of Jews, and their role in running the Slovak concentration camps.

Tuka's arrest and trial in 1929 where he was charged with espionage on behalf of the Hungarian government precipitated the reorientation of Hlinka's party in a totalitarian direction. The Nastupists gained control of the party and in 1935 it polled 30 percent of the vote but refused to join with what they believed was an illegitimate government.

In 1936 Slovak Populists demanded a Czechoslovak alliance with Hitler's Germany and Mussolini's Italy. In September 1938, the Slovak Populist Party received instructions from Hitler to press its demands for Slovak autonomy.

On March 9, 1939, Czech troops moved into Slovakia in reaction to radical calls for independence from Slovak patriots, including Tuka, who had recently been released from prison. On March 13, Hitler took advantage of this situation, and prompted Jozef Tiso, the Slovak ex-prime minister deposed by the Czech troops, to declare Slovak independence, but Tiso refused, and Slovak independence was only declared on March 14th due to an Act of the Slovak Assembly.

The remaining Czechoslovakia was incorporated into the Reich as a protectorate, not a part of Reich, but only a protected state. Tiso was them elected president on October 26th 1939 and immediately appointed Tuka as his Prime Minister.

Together with Internal Affairs Minister Alexander Mach, Tuka became the leader of the radical and pro-Nazi wing within the Slovak People's Party. This wing — enjoying little support among Slovaks — relied on the Hlinka Guard, i.e. the Rodobrana revived by Tuka when released from jail in 1938. He was also the vice-chairman of the Slovak People's Party.

By a decree issued on October 29, 1938, the Hlinka guard was then designated as the only body authorized to give its members paramilitary training, and it was this decree that established its formal status in the country. Hlinka guardsmen wore black uniforms and a cap shaped like a boat, with a woolen pompom on top, and they used the raised-arm salute.

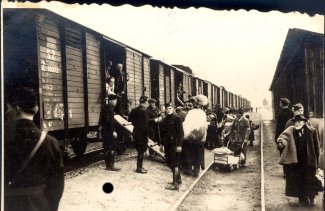

Tuka immediately began strongly advocated for the deportation of Slovakia’s Jewish population to the Nazi concentration camps. His anti-Semitic and radical policies put Prime Minister Tuka in stark conflict with the moderate President Tiso. But by March 26, 1942 the first trainloads of Jews deported from Slovakia embarked to their final destination at Auschwitz, and death camps in the Lublin area. The mechanism for rounding up the Jews and subsequent forced deportation was the Hlinka guard.

The deportations were carried out in Slovak trains by the Hlinka Guard and the Freiwillige Schutzstaffel, a volunteer detachment of Volksdeutsche SS-men, who jointly guarded the trains up to the border with the Generalgouvernement. At that point, the trains and their human cargo were handed over to the Germans, who escorted the trains to their destinations. In May 1942, Eichmann visited Bratislava to inspect the progress of the deportations. Some Jews were transported from the same departure points to the Slovak labour camps at Novaky, Vyhne and Sered. About 19,000 Jews – most of whom had certificates of exemption on the grounds that they were essential to the country's economy – remained in Slovakia. In addition, there were 3,500 Jews held in the three labour camps. Nearly 10,000 Jews avoided deportation by fleeing to Hungary.

By October 1942 the Hlinka guard had overseen the deportation of some 60,000 Slovak Jews, but then the deportations were stopped when it became clear to the populace, that Nazi Germany had not "only" abused the Slovakian Jews as forced labor workers but had also executed many of them in death camps.

Opposition to the deportations had been raised by the Protestant community and was soon followed by the Catholic church. Bishop Kmet'ko of Nitra organized public protests backed by the Vatican, and ensuing demonstrations had to be quashed secretly by Hlinka guardsmen.

As reports were passed to Tiso about the religious fervor that the Germans were murdering the Slovak Jews in Poland, he hesitated, and then refused to deport the remaining 24,000 Jews in Slovakia.

This act enraged Eichmann, and German troops moved in. Einsatzgruppe H of the Security Police and SD, whose duties included rounding up and killing or deporting the remainder of the Slovak Jews, accompanied the Wehrmacht into Slovakia. and the Jewish deportations were resumed in October 1944 but only after the Soviet army had reached the Slovak border and the Slovak National Uprising took place. As a result of the Uprising and the approach of the Soviet forces, Nazi Germany decided to occupy all of Slovakia and the country lost its independence and saw the deportation of Jews resumed again after two years.

During the 1944-1945 German occupation, another 13,500 Jews were deported and 5,000 imprisoned. The Hlinka guard once again took to rounding up, and persecuting Jews throughout Slovakia.

A small group called Náš Boj (Our Struggle), which operated under SS auspices, was the most radical element in the guard. Over the yeas the Hlinka Guard was forced to compete with the Hlinka party for primacy in ruling the country. However, this was no longer an issue for the guard after the anti-Nazi Slovak National Uprising in August 1944, when the SS took over and shaped the Hlinka Guard to suit its own purposes Slovak Gypsies, (Roma) were also persecuted by the Tiso regime as early as March 1939 but worsened greatly after the Slovak National Uprising. The German occupying authorities accused the Roman of complicity and insurrection, and then preceded with the wholesale roundups and mass killings of Gypsies throughout the region.

Hlinka Guardsmen were used to do the dirty work, killing suspect Roma rebels in front of their wives and children, then murdering the entire family. One Hlinka Guard unit operating in Lierny Balog rounded up sixty-five Roma men and forced them into a barn, then promptly set the barn on fire burning the entire structure and its inhabitants to the ground. Mass shootings of Gypsies families occurred in the valley of Vydrovo, and Hlinka guardsmen massacred the entire Roma community of Ilija, Slatina and Nresnice in November of 1944.

In 1945, the Republic of Czechoslovakia was resurrected, this time without the addition of Subcarpathian Ruthenia. The reborn Republic was to last until July 1992, when Slovakia again declared itself a sovereign state.

Sources:

Lettrich, Jozef. "History of Modern Slovakia" (F.A. Praeger 1955) Storm-Troopers in Slovakia: The Rodobrana and the Hlinka Guard, by Yeshayahu Jelinek The Jews of Czechoslovakia. Avigdor Dagan, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1984 The World Reacts To the Holocaust David S. Wyman, Charles H. Rsenzveig Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution By Richard S. ABC-CLIO, 2005 USHMM

Copyright: 2008 Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T |