Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Aktion Reinhard

A-R Leadership A-R Articles

Action Erntefest Modern Research

| ||||||

Aktion Reinhard Train Transports – Eyewitness Statements

Belzec Death Camp

Karl Maischein

Maischein was employed in the Ostbahn – Gedob office on Finkstrasse in Lublin.

Question: What job did you have with the railway in Lublin?

Answer: I was head of the railway traffic department.

Question: What do you know about the transport of Jews in the Lublin District?

Answer: In the railway district of Lublin transports with Jews travelled to various stations. I was not informed of the origins of the transports because they were all trains that arrived from outside the area as sealed trains and also left again as sealed trains.

Question: Are such places as Treblinka, Sobibor and Belzec known to you?

Answer: I only remember Belzec. It lay in the Russian border.

Question: Did transports of Jews go to Belzec?

Answer: Yes. How big they were I cannot say.

Question: To the knowledge of the members of the Investigation Commission, transports of Jews were directed to from Lublin to the places mentioned. Altogether 1,550,000 Jews were transported to the places named.

Answer: I can, as a matter of fact, only remember the name Belzec

Question: Did you, at any time, see transports with the code name “Aktion Reinhardt?”

Answer: The concept is not known to me. I must add here, however, that all transport of operations- of all kinds – ran under code names.

Question: Did you, as Director of the railway traffic department, deal with the Gestapo or SS offices? If yes, who was your opposite number?

Answer: I dealt mostly with SSPF Globocnik, in as far as I dealt with supply transports for the SS. I also had to deal with his subsidiary offices in this matter. I do not remember the names of these people. Of the names mentioned to me now, none arouse any memories.

Globocnik was the man in authority on Jewish questions.

Interviewed by officers of Sonderkommission “P” from Darmstadt

Stefan Kirsz

A Polish locomotive driver, who was in the Belzec station

“As a co-driver of a locomotive, I led the Jewish transports from the station of Rava – Russkaya to Belzec many times. These transports were divided in Belzec into three parts.

Each part, which consisted of twenty freight cars, were taken to the railway spur inside the camp pushed by the locomotive, and stopped near the former border wall of 1939/40 (outside the camp).

Immediately after the freight cars stopped inside the camp, they were emptied of the Jews. Within 3-5 minutes the twenty cars were empty of Jews and their luggage.

I saw that in addition to the living, corpses were taken out.

The Germans did not allow us to watch the camp, but I was able to see it when I approached the camp and deceptively pretended that I must put the coal closer to the entrance gate.”

Rudolf Reder

“The train moved at eight in the morning. I knew that the stoker and the engineer were German. The train moved quickly, but to us it seemed very slow.

It stopped three times, in Kulikow, Zolkiew and Rawa Ruska. The stops were probably needed for the coordination of rail traffic. During the stops, the Gestapo came down from the car roofs and prevented anyone from approaching the train.

They did not allow us even a drop of the water that people wanted to give, out of mercy, through the small grated window to those fainting from thirst.

About noon the train reached the Belzec station. It was a small station. Little houses stood around it. The Gestapo lived in these little houses. Belzec was on the Lublin – Tomaszow line, fifteen kilometres from Rawa Ruska.

At the Belzec station the train reversed from the main line onto a spur that ran another kilometre, straight through the gate of the death camp.

Ukrainian railroad workers also lived near the Belzec station, and there was a small post office. An old German with a thick black moustache got into the locomotive at Belzec – I do not know his name, but I would recognise him in an instant.

He looked like a hangman. He took command of the train and drove it right to the camp. It took two minutes to get to the camp. For the whole four months, I would always see that same bandit.

The spur ran through fields. There was completely open space on both sides, not a single building. The German who had driven the train to the camp got down and “helped.”

Shouting and lashing out, he drove the people from the train. He himself went into each car and checked whether someone remained there. He knew all the tricks. When the train was empty and checked, he signalled with his flag and drove the train out of the camp.

The whole terrain between Belzec and the camp had been taken over by the SS. No one was allowed to show himself there. Civilians who wandered in by mistake were shot.

The train pulled into a yard about a kilometre long and wide, surrounded by barbed wire and iron fencing, one atop the other, two metres high. The wire was not electrified.

You drove into that yard through a wide wooden gate topped with barbed wire. Next to the gate stood a hut where a sentry sat with a telephone.

In front of the hut stood several SS-men with dogs, when a train had passed through the gate, the sentry closed it and went inside the hut.

That was when the “taking delivery of the train”, took place.

Sobibor Death Camp

Jan Piwonski

In February 1942 I began working here as an assistant switchman.

The station building, the rails, the platforms are just as they were in 1942?

Nothing’s changed?

Nothing Exactly where did the camp begin?

If we go there, I’ll show you exactly. Here there was a fence that ran to those trees you see there. And another fence that ran to those trees over there.

So I’m standing inside the camp perimeter, right?

That’s right.

Where I am now is fifty feet from the station, and I’m already outside the camp. This is the Polish part, and over there was death.

Yes. On German orders, Polish rail-men split up the trains. So the locomotive took twenty cars and headed towards Chelm. When it reached a switch, it pushed the cars into the camp on the other track we see there.

Unlike Treblinka, the station here is part of the camp. And at this point we are inside the camp.

Where we are now is what was called the ramp right?

Yes, those to be exterminated were unloaded here.

So where we’re standing is where 250,000 Jews were unloaded before being gassed?

Yes.

Did foreign Jews arrive here in passenger cars too?

Not always. Often the richest Jews, from Belgium, Holland, France arrived in passenger cars, sometimes even in first class. They were usually better treated by the guards.

Especially the convoys of Western European Jews waiting their turn here, Polish rail-men saw the women making up, combing their hair, wholly unaware of what awaited them minutes later.

They dolled up. And the Poles couldn’t tell them anything, the guards forbade contact with the future victims.

Thomas (Tovi) Blatt

The passenger train usually arrived in the early morning, about 3.00 am, and stopped outside the camp at the small, obscure station amidst a wild forest.

From the outside nothing differentiate this passenger train from any other. Inside, every available seat was taken. The provisions for travelling in comfort – established at the point of departure in the Westerbork collection camp in Holland – functioned well. There were doctors and nurses for the sick, maids for the handicapped and babies. Food and medicine were in plentiful supply.

Soon eight to ten cars were detached and pushed onto a side track leading into the camp. The locomotive exited again, and the gate closed. German and Ukrainian guards were posted around the platform and waited.

Nearby stood a group of twenty young Jews dressed in blue overalls and blue German Mountain Troops caps with the insignia BK, for Bahnhofkommando (Railroad Station Detachment). At the Nazis signal they opened the carriage doors, ordered the people to alight, and helped with the heavy luggage.

Ada Lichtman

Ada Lichtman was deported from Hrubieszow to Sobibor death camp

“We were packed into a closed cattle train. Inside the freight cars it was so dense that it was impossible to move. There was not enough air, many people fainted, others became hysterical.

In an isolated place the train stopped. Soldiers entered the car and robbed us and even cut off fingers with rings. They claimed that we didn’t need them any more.

These soldiers who wore German uniforms spoke Ukrainian.

We were disorientated by the long voyage, we thought that we were in Ukraine. Days and nights passed. The air inside the car was poisoned by the smell of bodies and excrement.

Nobody thought about food, only about water and air. Finally we arrived at Sobibor.

Abraham Krzepicki

Treblinka Death Camp

He was deported from the Warsaw Ghetto on 25 August 1942 to the Treblinka death camp, and escaped after eighteen days in the death camp.

“At the Umschlagplatz we still hoped that some kind of separation would take place at the Umschlagplatz and we would be able to show our papers. But unfortunately we never had that chance.

As we came closer, we saw the boxcars ready for us and we said to each other, “Oy vey, we’ve had it. We’re in trouble.” And in fact the Lithuanian guards came straight over to us and started hitting us over the head with whips: they did not let anyone go near the Germans.

From the Umschlagplatz we were moved towards the box-cars. Only two foremen from Waldemar Schmidt’s shop managed to get through, they were in uniforms and army caps.

They went up to the Scharfuhrer, who was the old sadist, but he had a sudden inspiration. He looked them up and down for five minutes, then nodded and told them they could go. This was how these two men got away, but nobody else was that lucky.

We were moving closer to the box-cars, already we could see elderly people stretched out on the floor of the first car, half unconscious. We didn’t like the look of this. Then steps were moved up to the box-cars and the Lithuanian auxiliaries started driving us faster with their whips, up into the cars.

We had to give up all hope of being able to show our papers to somebody and so we got into the box-cars.

Over a hundred people were crammed into our car. The ghetto police closed the doors. When the door shut on me I felt my whole world vanishing. After the doors had closed on us, some of the people said “Jews we are finished.”

But I and some others did not want to believe that, “It can’t be,” we argued. “They wont kill so many people, maybe the old people and the children, but not us. We’re young. They’re taking us to work.”

At 4pm the train began to move again. We moved a short distance, then we saw the Treblinka station. As the train moved on, we saw whole mountains of smattes (rags).

The Jew at the window who was the first to see the rags again tried to calm the crowd, saying this would be our work. We would be put to work sorting out these rags.

Others wanted to know where the rags could have come from. They were told that in Majdanek near Lublin and in other camps the Jews had been given paper clothing and the clothing with which they had come had been gathered together, sorted out and forwarded to Germany, to be reconditioned.

Others volunteered that in Warsaw there was also a special shop at 52 Nowolipki Street, known as Hoffmann’s shop, where old clothes were reconditioned.

Minutes before the train pulled into Treblinka station, we saw Jews being taken to work. This too was reported to the others, and everybody was glad. Everybody was told that Jews were being taken to work, led by a Ukrainian.

After passing the Treblinka station, the train went on a few hundred metres to the camp. In the camp there was a platform to which the train ran through a separate gate, guarded by a Ukrainian.

He opened the gate for us. After the train had entered, the gate was closed again. As I was later able to note, this gate was made of wooden slats, interwoven with barbed wire, camouflaged by green branches.

When the train stopped, the doors of all the cars were suddenly flung open.

We were now on the grounds of the charnel house that is Treblinka.”

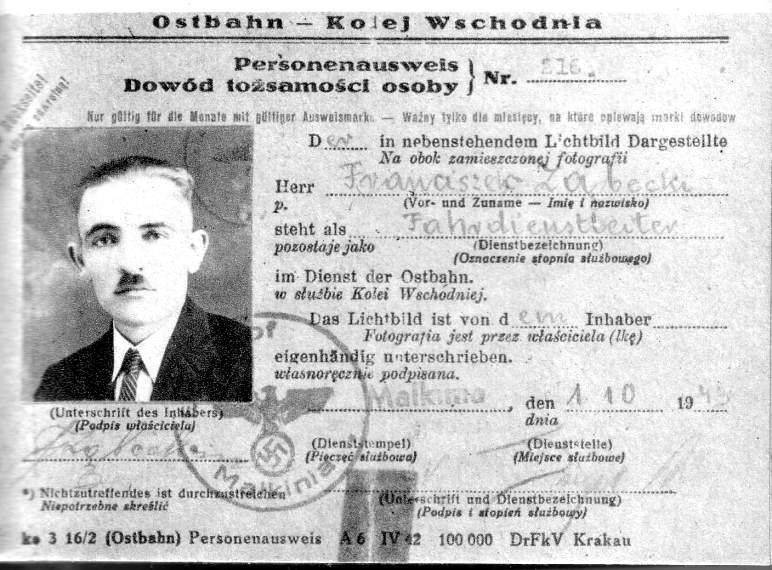

Franciszek Zabecki

Polish Station Master at Treblinka station

“The first transport of “deportees” left Malkinia on July 23 1942, in the morning hours. The train announced its approach not merely with a shriek of wheels as it crossed the Bug bridge, but with a volley of rifle and machine gun fire from the security guards.

The train entered the station it was loaded with Jews from the Warsaw ghetto.

Four SS men from the new camp were waiting. They had arrived earlier by car and asked us how far from Treblinka the “special train with deportees” was.

They had already received word of the train’s departure from Warsaw. A smaller engine was already at the station, waiting to bring a section of the freight cars into the camp.

Everything was planned and prepared in advance. The train was made up of sixty closed cars, crowded with people. These included the young and elderly, men and women, children and babies.

The car doors were locked from the outside and the air apertures barred with barbed wire. On the car steps on both sides of the car and on the roof, a dozen or so SS soldiers stood or lay with machine guns at the ready.

It was hot, and most of the people in the freight cars were in a faint.

As the train approached, an evil spirit seemed to take hold of the SS men who were waiting. They drew their pistols, returned them to their holsters, and whipped them out again, as if they wanted to shoot and kill.

They came near the freight cars and tried to calm the noise and weeping, then they started yelling and cursing the Jews, all the while calling to the train workers, “Tempo, fast.”

Then they returned to the camp to receive the deportees.”

Henrik Gawkowski

Polish locomotive driver for the Ostbahn, who drove transports of Jews to Treblinka death camp.

Did he hear screams behind his locomotive?

Obviously, since the locomotive was next to the cars. They screamed, asked for water. The screams from the cars closest to the locomotive could be heard very well.

Can one get used to that?

No. It was extremely distressing to him. He knew the people behind him were human like him. The Germans gave him and the other workers vodka to drink.

Without drinking, they couldn’t have done it. There was a bonus- that they were paid not in money, but in liquor. Those who worked on other trains didn’t get this bonus.

He drank every drop he got because without liquor he couldn’t stand the stench when he got here. They even bought more liquor on their own, to get drunk on.

From what I know that was very rare, Jews shipped in passenger cars. Most arrived in cattle cars.

It’s not true.

It’s not true? What did Mr Gawkowski say?

She said he may not have seen everything. He says he did. Once, at the Malkinia station, for example, a foreign Jew left the train to buy something at the bar. The train pulled out and he ran after it, to catch it up.

Did Mr Gawkowski – aside from the trains of deportees – he drove from Warsaw or Bialystok to the Treblinka station – did he ever drive the deportee cars from the Treblinka station?

Two or three times a week for around a year and a half.

That is, throughout the camp’s existence?

Yes this is the ramp.

Here he is, he goes to the end with his locomotive, and he has the twenty cars behind him.

No, they’re in front of him. He pushed them.

Franz Suchomel

SS- Unterscharfuhrer Treblinka Death Camp

What was Treblinka like then?

Treblinka then was operating at full capacity

Full Capacity

Full capacity!

The Warsaw ghetto was being emptied then. Three trains arrived in two days, each with three, four, five thousand people aboard, all from Warsaw.

But at the same time, other trains came in from Kielce and other places. So three trains arrived, and since the offensive against Stalingrad was in full swing, the trainloads of Jews were left on a station siding.

What’s more, the cars were French made of steel. So, that while five thousand Jews arrived in Treblinka three thousand were dead in the cars. They had slashed their wrists, or just died.

The ones we unloaded were half dead and half mad.

In the other trains from Kielce and elsewhere, at least half were dead. We stacked them here, here, here and here. Thousands of people piled one on top of another on the ramp. Stacked like wood.

In addition, other Jews still alive, waited there for two days: the small gas chambers could no longer handle the load.

They functioned day and night in that period.

Sources: Belzec by Rudolf Reder published by Panstwowe Muzeum Oswiecim – Brzezinka 1999 Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka by Yitzhak Arad published by Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987 Shoah – An Oral History of the Holocaust by Claude Lanzmann published by Pantheon Books New York 1985 Sobibor – Martyrdom and Revolt by Miriam Novitch published by Holocaust Library New York 1980 The Death Camp Treblinka by Alexander Donat published by Holocaust Library New York 1980 Holocaust Historical Society

Some Photos -Private Collections

Copyright. Chris Webb, Lars Christen H.E.A.R.T 2008

|