Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Aktion Reinhard A-R Leadership

A-R Articles

Action Erntefest Modern Research

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Labour Camps – Belzec , Sobibor and Treblinka Belzec

The establishment of work camps for Jews from the General Gouvernement in Belzec in 1940 was undertaken for many reasons. According to the Nazi plans the initial idea of building labour in the Lublin district was connected with the plans to resettle all Jews from Germany and its annexed territories to the Lublin district, as well as making cities in the General Government free of Jews, such as Krakow, where Frank announced on 14 April 1940 that he intended to make the city Jew free. The official excuses for the resettlements were often ingenious at Kazimieraz Dolny, the excuse was quite original. The place was a romantic “painters nook” and the Jews were turned out in the course of a “beautification action”. Another reason was the idea of Himmler and Heydrich to use the Jews for building border fortifications between the General Gouvernement and the Soviet Union. The Nazis published a forced labour degree on 13 January 1940, and Chaim Kaplan noted in his diary – “this decree will uproot all of Polish Jewry and bring utter destruction upon it”. The Jews were to be resettled from the Warthegau and other Polish cities, the responsibility for the creation and management of the labour camps in the border area fell to Odilo Globocnik the SS and Police Leader for the Lublin district. From the end of May 1940 until August 1940 approximately 10,000 Jews from Lublin, Radom, and Warsaw district were sent to Belzec. They came as volunteers unaware of the conditions in the camp. Adam Czneriakow wrote in his diary that according to a German Army report dated 23 September 1940, in Belzec labour camp meals consisted of bread, coffee, potatoes, and occasional morsels of meat – no fats, fruits or vegetables. There was widespread dysentery. Clothing was not issued, the workers were human figures in rags. Work was scheduled for seven days a week and there was no opportunity to wash. The men slept crowded on the hard floor. For medical care they were dependent on Jewish doctors and “sanitation” men. A large group of Jewish workers arrived in Belzec during three days in August 1940, in the beginning they had to lodge in primitive cramped conditions. After several days they were sent to twenty different sub-camps which were located in Belzec, and its surrounding area. Their main task was building fortifications along the border with the Soviet Union, a rampart of 140 kilometers between the Bug and San rivers. In fact until October 1940 the “Eastern Rampart” was only 40 kilometers long – between Belzec and Dzikow Stary village, 2.5 meters deep and 7.5 meters wide. The prisoners of the Belzec work camps built a 6 kilometers fortification – this work was connected with the building of defence fortifications, known as the “Otto Line”, and this was managed by Richard Thomalla, from the SS- Zentralbauleitung in Zamosc. In Belzec Jewish prisoners lived at three sites, the manor – 1000 people, Kessler’s Mill – 500 people and in the locomotive sheds – 1500 people. Prisoners also worked in other locations such as Cieszanow – 3000 people, Plaszow -1250 people. Some of the workers at Cieszanow were eventually sent to Dzikow. The Jews were not only employed on building defence fortifications, but also built roads, and regulated rivers. Thirty five forced labour camps were established along the “Otto Line”, mainly set up in abandoned synagogues, warehouses, granaries and barns. When the first group of Jews from Lublin arrived in Belzec they met the Romany Gypsies resettled from Germany, Czechoslovakia and Poland. The Governor of Lublin Zorner decreed that Belzec should be the central camp for Gypsies, and their camp was located on a farm at Belzec Manor. The Gypsies were employed on digging ditches. Among the Jews deported from the Reich were World War One veterans and even members of the Nazi party, in addition a group of Polish farmers from villages near Tomaszow Lubelski were arrested for not having provided food to the Germans. The conditions in the camps were terrible – the workers were tortured, beaten and starved. Often mothers decided to kill their babies because they had no food for them. Every day they received so-called black coffee without sugar and 300 grams of bread for breakfast. The “soup” was mainly water with smelly vegetables and old meat. For the hard working prisoners this was insufficient. Only during a visit of the Swiss Red Cross was the food improved, and when the delegation left Belzec to visit Plaszow forced labour camp near Belzec, the commandant SS- Sturmbannfuhrer Herman Dolp, ordered that the prisoners should receive the normal poor quality fare. Many Gypsies died because of typhus and dysentery, they were buried in Belzec near the Lublin – Lwov railway and the road to Jaroslaw, the number of victims is not known. When the first Jewish prisoners came to Belzec, more than 1,000 Gypsies were transferred to Krychow Labour Camp near Sobibor, formerly in pre-war times, a work camp for Polish criminal prisoners. There is no clear information available about the fate of these Gypsies, but it is likely that some were sent to the Siedlce ghetto, and from there they were deported to Treblinka death camp. The commandant of the Belzec labour camps complex was SS- Sturmbannfuhrer Herman Dolp. Before this he was camp commandant of the Lublin Forced Labour camp at 7 Lipowa Street in Lublin. In Belzec he was assisted by SS-Hauptsturmfuhrer Franz Bartetzko, who was later to become Commandant of the Forced Labour Camp at Trawniki.

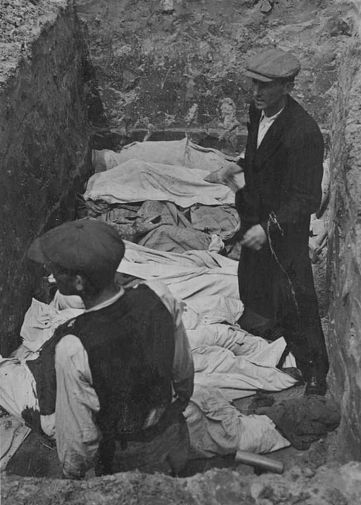

Both men were very cruel and killed many prisoners. The most infamous example of Dolp’s cruelty was that he ordered Jews to go to the latrines only at a specified time – those who he found at the latrines outside of this time, were killed by him. Many prisoners had diarrhoea, and thus they became his victims. Dolp was also known as the most corrupt SS man in Belzec. The prisoners who worked in the workshops had to produce clothes, shoes etc for Dolp’s private requests. Though the camps were controlled by the SS the supply of food, clothes and administration was managed by the Judenrat of Lublin. In Belzec the Germans established a so-called Jewish Gremium, responsible for the organisation and distribution of food within the camps. All costs resulting from the upkeep of the Jewish prisoners were paid for by the Judenrat’s of the towns, where the Jews originated from. After August 1940 the Gremium name was changed into the “ Central Camps Council” led by Leon Zylberajch from Lublin. All members of the “Camps Council” were released from work. In reports written by the Lublin Judenrat in 1940 after the closure of the labour camps, much evidence of corruption, the “Camps Council” members pressed the prisoners to pay when they had to go to hospital, the prisoners had to pay for better jobs, when they returned. Also the “Council” members plundered the food parcels sent by the prisoners. The work in Belzec and the other labour camps was extremely hard – the prisoners started working at 0600 hours. Because of tortures, hunger and primitive living conditions, many of the workers looked like skeletons after only a short time. Dr Janusz Peter, chief of the Tomaszow Lubelski hospital who maintained contact with the workers, described them as “spectres in rags”. In his memoirs one can read that the Germans took photos of these workers as “examples of the sub-human Jewish culture in Poland”. The precise number of victims in all of the Belzec Labour camps complex is not known, but within the village an estimate of 300 Jews lost their lives. The Labour camps in Belzec and nearby villages were abandoned in October 1940. Before the liquidation of the camps some of the Jews had to be released because they could not work anymore. Some of them died after their release. The last transport of released prisoners was sent to Hrubieszow in late October 1940. According to Polish witnesses around 200 victims are buried in the old park near the manor. Many others are buried in the forest near Jan Woloszyn’s house - the exact location is still unknown, probably the forest opposite to the death camp, behind the furniture factory and Wirth’s house. Other victims were buried in the Jewish cemetery in nearby Tomaszow Lubelski Sobibor

In accordance with German plans at the very beginning of the occupation of Poland, the Lublin district was intended to become the crux of the Generalgouvernement’s agriculture. In order to modernise the agriculture in this region, the German civil administration wanted to regulate the small rivers and to improve the meadows.Therefore the Wasserwirtschaftsinspektion – Inspection for Water Economics in the Lublin district installed a network of small work camps in 1940. Jewish and Polish prisoners worked in this camps. Chelm Country became one of several centres for these camps, later on the death camp at Sobibor was established in the spring of 1942. In 1940 Jews from the Lublin and Warsaw were sent to these work camps, their salary was 96 zloty per month, a poor reward for extreme hard work. These forced labour camps were set up in the swampy surroundings of Sobibor:

In some places the camps were located in school buildings, abandoned farms or former industrial buildings. Except for the Krychow camp the prisoners lived in barns, on private farms or in a mill, in the case of Staw – Sajczyce. The camps were under the supervision of the German civil administration but the prisoners were guarded by Trawniki SS men or by Jewish police in Osowa. In Sawin the Jewish prisoners were supervised by Jewish police and Polish guardsmen who worked for the Wasserwirtschaftinspektion.

The prisoners were forced to work 8 -10 hours per day. Most of the time they stood in the rivers in wet clothes, without the opportunity to change them. Food was always a major problem. Only those who came from towns close to the camps had the opportunity of obtaining some food from home. The Jews taken from the Warsaw ghetto or the Warsaw district depended on the camp’s kitchens. If they had some money they could buy bread from the local peasants. In some camps like Krychow, the prisoners were killed when camp commandant Adolf Loffler discovered contacts with local Poles. The Polish farmers accused of selling food to the prisoners were beaten. In Osowa contacts with the Polish farmers were not so strictly forbidden. Because they had no money the Jews exchanged their clothes for food. In 1941 alone, 2500 out of 8700 Jews from the Warsaw ghetto had to be released from the camps because of sickness. Many Jews died of starvation, typhus epidemics, and extreme heavy labour. In several camps like Osowa and Sawin they were shot in mass executions. In the autumn of 1941 in Osowa the last remaining group of 58 Jewish prisoners were executed close to the camp. Two of them survived and became functionary prisoners in the next period between 1942 and 1943. In 1941 about 2200 Jews from the Warsaw ghetto were sent to Krychow, Osowa, Sawin and Staw – Sajczyce. The number of Jews who were released from these camps during June / July 1941 is not known. All the large buildings were taken over by the German Wehrmacht in preparation for the attack on the Soviet Union. In Osowa the average number of prisoners was 400 – 500 people, in Siedliszcze approximately 2,000 and in Sawin 700-800. Krychow was the biggest camp in this network, located south –west of Sobibor close to Hansk village. In 1940 the Hansk local administration received an order from the German civil administration to prepare buildings in the former camp for Gypsy deportees. These were relocated from the Gypsy camp in Belzec. The whole group has been estimated at between 1000 and 1500 people. According to the statements by Polish witnesses from Hansk, the Gypsies in Krychow were not guarded and not forced to work. Most of them could not speak Polish, they exchanged their clothes for food and begged for money. In the autumn of 1940, they were deported from Krychow. Some of them were sent to the Siedlce ghetto. Between the end of 1940 and early 1941 most of the prisoners in Krychow were Jews from the Warsaw ghetto and local Polish farmers arrested for not having paid their impositions. Around 1500 prisoners in Krychow, according to witnesses in Hansk, were beaten by the guards and suffered from starvation and illness. 150 Jews worked as manual workers. Many Jews had to work on fields which belonged to the German “colonists” or at the manors taken over by Germans. Even women and children aged between 8 -12 years of age had to work in these camps. With the beginning of Aktion Reinhard all of these forced labour camps were reserved for Jews only. After their families paid for them, the Polish and Ukrainian prisoners were released at the beginning of 1942.

When the Germans started to liquidate the Jewish ghettos, in places such as Rejowice, Siedliszcze, Sawin, Wlodawa and Chelm, the Jews were deported to work camps or direct to the death camps, or were deported to work camps, and then onto the death camp at Sobibor. Franz Stangl the commandant of the death camp in Sobibor describes his arrival in the Sobibor area, just before taking up the post of death camp commandant: “The first camp I saw was about half-way between Cholm and Sobibor, a farm called Krychow (Kirchof in German). It employed two to three hundred Jewish women, mostly German or at least German speaking. I went in there to look around. There was nothing – you know – sinister about it – they were quite free. If you like it was just a farm where the women worked under the supervision of Jewish guards. Well I suppose you could call them Jewish police. As I say I looked around and the women seemed quite cheerful – they seemed healthy. They were just working you know. The guards were armed with weissen Schlagmitteln - literal translation white implements for beating. We got to the village of Sobibor around supper-time. In the middle of the village there was another work camp. The man in charge carried a gun and wore a blue uniform I wasn’t familiar with – he took me to a barrack where we had supper. Jewish girls served us – during the meal he described the work that was being done there, it was mostly drainage.” In Sobibor selections were sometimes made on the ramp, for workers in the Labour camps, for transports arriving from Slovakia, Germany, Austria and Holland. Sobibor was virtually unique, with selections made on the ramp, for work in other locations, whilst the vast majority of the arriving transports went straight to the gas chambers. The number of deportees selected for work in forced labour camps such as Budzyn, Dorohucza, Poniatowa and Trawniki is not known, but some people managed to survive the war. Apart from the harsh working conditions, in spring and summer mosquitoes were a big problem, selections in the camp were regularly organised. Sick people and children were sent by horse-drawn vehicles or on foot to Sobibor death camp. In the labour camps which were located close to Sobibor death camp the inmates knew about the death camp and this psychological pressure shattered their will to resist and survive. In many Polish testimonies the witnesses mentioned the passivity of the prisoners. In Osowa village, 7 kilometers away from Sobibor and surrounded by a large forest, no prisoner escaped from the labour camp although some Poles attempted to help them. Only during the final liquidation of the Adampol Work Camp near Wlodawa on 13 August 1943 some of the inmates who were in contact with local partisans tried to organise some resistance and fight with the police guarding them. It is important to mention that most of the inmates were Polish Jews who knew their fate. During the liquidation of Adampol labour camp 475 Jewish prisoners were executed on the spot.

Most of the Jews deported from outside the Generalgouvernement had little possibility of escaping because they could not speak the language, and did not know the local population or region. In Sawin successful escapes by two Czech Jews are known. One of those who escaped, who lost his mother during the selection in Sawin, only found out after the war that his camp was not far away from the death camp in Sobibor. In other camps Polish witnesses often mention close contacts with Czech Jews. Polish farmers realised that among the deportees were Jews who had converted to Christianity. For example in Sawin a dentist from Czechoslovakia was a member of the church choir and her son played the violin during mass. Christian Jews from Czechoslovakia were also in Krychow. Zygmunt Leszczynski from Hansk gave a statement – “Among the Jews who were in the camp in Krychow there were also Catholics. I saw how during a transport to Krychow some of them stopped before the cross which was close to the street and they crossed themselves and prayed. I saw also that some of them wore small crosses on their chests.”

In the summer and autumn of 1943 most of these camps were liquidated and their inmates were sent to Sobibor death camp. From Krychow the prisoners were taken on horse-drawn wagons, from Sawin they were made to walk and those who could not keep up, were killed along the way. Henryk Stankewicz from Sawin witnessed the scene – “I remember we were together with my father in front of our house, 5 -8 meters away from the street. Suddenly we saw the “Kalmuk” (probably a Ukrainian Guard) and behind him several hundred marching people in a column. They walked very slowly and looked starved and dirty. Several of them took off their hats and told us words of farewell. “Goodbye Mr Stankiewwicz we are going to the fire.” After the selections in the labour camps during their liquidation the Germans forced the Polish farmers to use their horse-drawn wagons to transport the old people and the invalids. Just before the main gate of the death camp in Sobibor the Poles had to abandon their wagons and Ukrainian guards from the camp drove the wagons through the gate. Then the Polish farmers heard the victims screaming and after one or two hours the wagons were brought back to them. Probably the last labour camp to be liquidated was in Luta village. The camp existed, according to the testimonies of local inhabitants, until October 1943, and was liquidated just after the revolt. Prisoners in Luta labour camp witnessed groups of prisoners escaping from Sobibor attempting to escape to the nearby forest. Today very little remains of these work camps, in Osowa there is a small cemetery with graves of prisoners who died there, and at Adampol there is a small memorial. It is impossible to provide a precise figure of how many Jews were killed in the Sobibor area work camps, and further research is required to determine this. Treblinka The Treblinka labour camp (Arbeitslager Treblinka) was located near the sandpit at the edge of the forest and it was about 1.5 kilometers from the death camp. The camp came under the control of the SS and Police Leader Warsaw. It operated from June 1941 until 23 August 1944, about 2000 prisoners mainly Poles, although there were some Jews from both Poland and other countries lived in wooden barracks situated in the forest.

They worked at the nearby gravel pit, unloading freight trains at the Treblinka station, at road construction and at tree felling. From April to June 1942 a group of prisoners from the Arbeitslager Treblinka dug foundations at the site of the Treblinka death camp. A concrete road that ran from Kosow Lacki village through the forest to the labour camp, was built by the prisoners of Treblinka labour camp, and this was known as the Czarna Droga, and this can still be seen today. Czarna Droga means Black Road. Alexsei Kolgushkin, a former Trawniki – SS guard made a statement on 24 September 1980 in the city of Rybinsk regarding his service at the Treblinka Labour camp: "At the end of July 1943, the exact day I cannot give, together with a group of about 20 – 25 guards, whose names I don’t remember now, I was sent to the camp in Treblinka. While I was in Treblinka I found out there were two camps located there, located about two kilometres from each other. One of these camps, which was situated closer to the Malkinia railroad station, was a death camp where massive executions of citizens of Jewish nationality, who came from countries occupied by the Germans. This camp was surrounded by barbed wire and was camouflaged by spruce branches. The second camp I was sent to, to perform guard duty was a labour camp – these two camps in Treblinka were called camp number one and camp number two by the guards, which one was number one and which was number two is difficult for me to say. Near the entrance to the work camp where I served there was a barrier and guard tower. The portion of the camp that contained the prisoners was isolated from the camp in general. This area that contained the prisoners was surrounded by a double barbed-wire fence, which in turn contained a patrolled region between the two fences. This controlled region consisted of a strip of ploughed earth where the footprints of anyone who crossed it would be left. The entire camp area was surrounded by a single barbed wire fence, there were buildings situated in the camp that held clothing, there were warehouses and stables also. There were barracks where the guards lived and there were barracks where the German’s from the camp administration lived. None of the guards were permitted to enter the area where the prisoners were kept, and the guards were forbidden from entering the controlled region. The area containing the prisoners was divided into three sections: One section contained a kitchen, stoves and sewing shops. The Jewish prisoners who were artisans lived there along with Jewish tailors, barbers, stove workers and drivers. They were dressed in civilian clothes , each wore their own clothes. In the next section the Jews who were used for forced labour were lived. They were dressed in striped uniform and they wore wooden shoes on their feet. I do not know if there were skilled labourers among these Jews, who had a speciality. They were sent to work in the sand pit where they hauled sand, they were also taken to work in the forest removing tree stumps. The sand from the sand pit was sent off in the direction of the Malkinia station. In the third section of the camp were kept the Polish prisoners. As a rule the Poles were used for auxiliary work in the camp – they were dressed in civilian clothes, like the Jewish skilled workers. I do not know if their food was on the same level as that of the other prisoners. The guards were divided into sections, platoons and companies. The camps administration was made up of Germans only – they occupied the supervisory positions. The guards were divided into four sections, each containing 12 -15 men. Besides providing security for the camp the guards took the prisoners to work by convoy and they guarded them during work. I do not know who shot prisoners on the way to work. I personally had occasion to take prisoners by convoy to the sand pit and accompany them into the forest to remove tree stumps and to auxiliary jobs – in general wherever they went to work. I also often led prisoners by convoy to the Malkinia railway station where they worked unloading and stacking. In the area of Treblinka work camp, while leading prisoners to work by convoy and, in particular, to the Malkinia railroad station, I was constantly seeing a thick black smoke rising above the Treblinka death camp. At those times I smelt the pungent odour of burning flesh. I understood they were burning human bodies in the death camp – other guards said so too, but who in particular said so I do not recall now. In the spring of 1944 the exact month I do not remember, the prisoners of the death camp organised an uprising and fled. Some of them were beaten back by the guards and the remaining ones ran." (Note the date of the uprising was August 1943) After this the Germans destroyed the camp buildings and ploughed up the area. The work camp in Treblinka where I continued to serve was in existence up to approximately July – early August 1944. We the guards were not informed of this. In the morning the Germans came and told us we would have to increase camp security. I saw that Gendarmarie was approaching from the town – the Gendarmarie were coming on the eve of the liquidation of the camp. On the day the camp was destroyed our division was on patrol duty – along the controlled region. Supplemental patrols were deployed next to ours in order to guard the area where prisoners were being held. On that day our division was at normal strength, however in the morning camp security was, as I said strengthened. At approximately 8 or 9am the prisoners began to be led out of the barracks. They were led out by the Germans and were assembled in the yard, the guards who were not on patrol also participated in this. After they were all assembled they began to beat them in groups of five and forced them to the ground. After counting out a certain number of prisoners they raised them up and made them pull their pants down to their knees, so they could not run, and these groups were led out into the forest, where in previously dug holes, they were all shot. The above mentioned holes had been dug in advance by the condemned themselves – they were led there in convoy by the guards, including myself. I did not know what these holes were for and I understood their purpose only on the day the prisoners were executed. In all there were several holes dug in the forest, the exact number I do not remember – they were approximately 40 – 50 meters in length, and 4-5 meters in width. Approximately 500 – 600 prisoners were executed in these holes in all. This figure is an approximate one since I did not count the number of people condemned to death. I only remember that when I walked up to these holes the second day, I saw they were filled up with bodies and dirt. After the liquidation of the camp the Germans and the guards fled together, since Soviet troops were already advancing on Treblinka. Note the camp was liquidated on 23 August 1944. The commandant of the Treblinka Labour camp was SS- Sturmbannfuhrer Theodor van Eupen born 24 April 1907 in Dusseldorf, SS Number 4528, he died on 14 December 1944 in Jedrzejow fighting partisans. Van Eupen participated in the January 1943 aktion to remove Jews from the Warsaw ghetto, and according to Marek Edelman an unarmed group of Bund members refused to board the train at the Umschlagplatz and the SS commander Von Eupen shot and killed sixty of the resisters. Franciszek Zabecki, the Polish railroad worker at Treblinka station, also confirmed Van Eupen’s brutality - “Von Eupen was a sadist who ill-treated the Poles and Jews working there, particularly the Jews, taking shots at them, as if they were partridges”. Other members of the SS staff at the Treblinka Arbeitslager were:

The average number of people detained in the camp was between 1000 – 1200 inmates, but throughout the camps existence more than 20,000 passed through the camp, and it is estimated that more than half this number perished. Today visitors can still see several remnants of the former camps buildings, concrete barrack foundations, the ramp, a swimming pool for the SS men, the camps administration barrack foundations, the gravel pit, and memorials for those killed by the Germans, during the camps existence.

Sources: Dokumenty I Materialy Vol 1 Obozy Red. N. Blumenthal Lodz 1946 Wiezjenia i obozy pracy w dystrykcie lubelskim w latach 1939 – 1944 by E. Dziadosz and J. Marszalek – Zeszyty Majdanka Vol 3 1969 W Belzcu podczas okupacji Tomaszowskie za okupacji by Dr Janusz Peter – Tomaszow Lubelski 1991 Lubelska dzielnica zamknieta by T.Radzik Lublin 1999 State Archive Lublin – Collection of Judenrat in Lublin 1939-1942 The Warsaw Diary of Adam Czerniakow published by Elephant Paberbacks Chicago 1999. The Final Solution by G. Reitlinger – published by Vallentine Mitchell 1953 Archive of the Institute for the National Remembrance in Lublin. Documents about the investigations on the Mass Crimes in the Work Camps in Krychow, Siedliszcze and Adampol. State Archive in Lublin – Collection of the Governor of the Lublin District Interview with Mr. Stefan Ostapiuk from Osowa – from the private collection of Robert Kuwalek Obozy pracy przymusowej dia Zydow w dystrykcie Lubelskim by T. Berenstein – Biuletyn ZIH nr 24 – 1957 Zydzi warszawscy w hitlerowskich obozach pracy przymusowej – by T. Berenstein – Biuletyn ZIH nr 67 – 1967 Wiezjenia i obozy pracy w dystrykcie lubelskim w latach 1939 – 1944 by E. Dziadosz and J. Marszalek – Zeszyty Majdanka Vol 3 1969 Przyczynek do historii getta w Sawinie by J. Krasnodebska – Rocznik Chelmski vol IV – 1998 Zydzi warszawscy w Lublinie I na Lubelszczyznie w latach 1940 -1944 by J. Marszalek Zydzi w Lublinie. Materialy do dziejow spolecznosci zydowskiej Lublina by T. Radzik Into that Darkness by Gitta Sereny – published by Pimlico 1974 Extermination Camp Treblinka by Witold Chrostowski – published by Vallentine Mitchell 2004 The Jews of Warsaw 1939 – 1943 by Yisrael Gutman – published by the Harvester Press 1982 Holocaust Historical Society Trebkinka Nigdy Wiecej by Edward Kopowka – Muzeum Walki I Meczenstwa W Treblince 2002

Copyright: 2007 SJ H.E.A.R.T

|