Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Treblinka

Treblinka Galleries Treblinka Articles -------------

A-R Leadership

A-R Articles

Action Erntefest Modern Research | |||||||

Treblinka Death Camp History

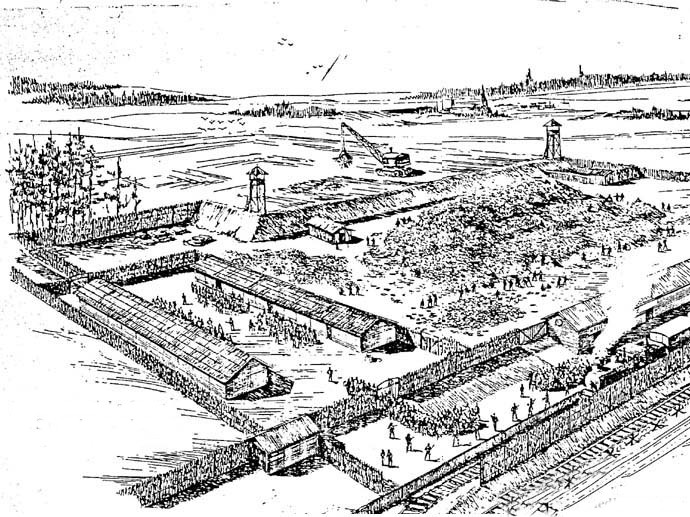

The death camp at Treblinka was located in the north-eastern region of the Generalgouvernement, in a sparsely populated area near Malkinia Gora, a junction on the Warsaw – Bialystok railway line, some 4km northwest of the small Treblinka village and its railway station. Near to an established Arbeitslager (forced labour camp) known as Treblinka l, the site chosen was heavily wooded and well hidden from view. Treblinka I housed both Poles and Jews, and was located by a gravel pit, one and half km from the site of the death camp. The labour camp functioned from June 1941 until 23 July 1944. The death camp was established as part of Aktion Reinhard. Construction work began at the beginning of April 1942, after SS men came to the village of Poniatowo and inspected the locality. The building contractors were the German construction firms `Schonbronn’ from Leipzig, and `Schmidt – Munstermann’, which had an office in Warsaw. SS- Hauptsturmführer Richard Thomalla from the SS-Bauleitung Zamosc supervised the construction work. Primarily, the workers building the death camp were Jews brought there in trucks from neighbouring villages, such as Wegrow and Stoczek Wegrowski. Prisoners, mainly Polish, from the Treblinka l labour camp were also utilised in the building work. The witness Lucjan Puchala recalled: “Initially we did not know the reason for building the branch track, and it was only at the end of the job that I found out from conversation among the Germans that the track was to lead to a camp for Jews. The work took two weeks and it was completed on 15 June 1942. Parallel to the construction of the track, earthworks continued.

The SS-men and Ukrainians supervising the work killed a few dozen people every day, so that when I looked from the place where I worked to the place where the Jews worked, the field was covered with corpses. The imported workers were used to dig deep ditches and to build various barracks. In particular, I know that a building was built of bricks and concrete, which as I later learned, contained people to be exterminated”.

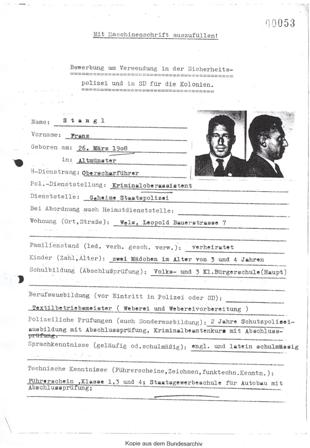

The camp’s first commander was the Austrian SS-Obersturmführer, Dr Irmfried Eberl, who had served in Bernburg (a “euthanasia” killing centre), and also, for a short time, at the Sobibor death camp. In August 1942 Eberl was relieved of his command by Globocnik, when Globocnik and Wirth visited Treblinka, having been made aware of a chaotic breakdown in the extermination process.

This had arisen because Eberl had accepted more transports than Treblinka could handle. In late August Eberl was replaced by SS-Obersturmführer Franz Stangl, the former commander of the Sobibor death camp. Christian Wirth stayed in Treblinka to sort out the chaos created by Eberl, and brought several experienced SS-men from Belzec, such as Franz and Hackenholt, to assist with the task.

The camp staff of Treblinka, responsible for the smooth operation of the mass killings, consisted of about 35–40 Germans, all of whom wore the field-grey uniform of the Waffen-SS. None of them held a rank lower than SS-Unterscharführer.

They came either from the Waffen-SS, or from the General (Allgemeine) SS, but some had previously served with the Police, and many had experience of working at various “euthanasia” killing centres. Men like Franz, Kuttner, Miete, Mentz, Hirtreiter, and Matthes, were already brutal mass murderers. In addition to the Germans, there were approximately 90– 120 Ukrainian auxiliaries, who mainly assisted with guard duties.

As distinct from the Germans, these men wore black uniforms, and were armed with carbines; the German camp staff all carried pistols, and sometimes sub-machine guns. Most of the Ukrainian guards were former Soviet prisoners of war who had volunteered to serve the Germans, and had been trained at the Trawniki camp. \

Some of them were of German extraction (the so-called Volksdeutsche), and certain of the latter were appointed platoon or squad commanders. Some Ukrainians were also used to operate the gas chambers, amongst them the infamous Ivan Marchenko and Nikolay Shaleyev.

700-1,000 Jewish inmates performed the manual labour, including certain aspects of the extermination process, and in addition attended to the personal needs of the SS staff. Groups of Jewish specialists were employed on construction work, cutting pine branches in the forest to be used as camouflage for the barbed wire fences, but most Jewish labour was used in sorting and bundling the clothes, goods, and valuables taken from their murdered fellow Jews. The prisoners were selected for labour from incoming transports, and most were killed within a short time, particularly in the early days of the camp.

In September 1942, Stangl introduced a permanent cadre of Jewish workers. Some worked at the ramp receiving the transports; these were known as “Blues”, for the blue armbands they wore. The undressing commando were known as the “Reds”, because of their red armbands. A further commando worked in the upper camp – the extermination area.

The camp was laid out in an irregular rectangle 400m by 600m, and was surrounded by a barbed wire fence intertwined with tree branches to block any view into the camp from the outside. A second outer fence consisting of barbed wire and anti-tank obstacles called `Spanish Horses’, was also constructed at a later stage. Watchtowers 8m high were placed at each of the four corners of the camp, and additional towers were built in the extermination area.

The camp was divided into zones of nearly equal size - the SS and Ukrainian living area, the Auffanglager (the reception area), a great sorting barracks (the Wohnlager), the Jewish living and working quarters, and the Totenlager, also known as the upper camp. A 100m by 100m square was separated from the rest of the camp by a barbed wire fence. It contained three barracks forming a “U” shape. Here the Jewish prisoners who worked in the lower camp spent their nights. At the far side of the roll-call area of this section was the latrine, covered by a straw roof.

The transports arrived at the reception area in the southwest section of the camp. This area included the railway track, the station platform, which was 200m long, and the fake station. At the rail entrance on the spur into the camp a wooden gate was wrapped in barbed wire intertwined with tree branches. The railway line ended with a wooden buffer, and a wooden gate which was permanently locked. The Lazarett, a small execution site, was also in the reception area.

Those too ill or too weak, or those who would impede the flow to the gas chambers, such as the disabled and unaccompanied children, were taken to a fenced-in area with a small wooden building, from which flew a Red Cross flag. After undressing in a waiting room that contained red sofas, they were shot in the back of the neck and thrown into a pit in which a fire constantly burned. Kapo Kurland was in charge of the Lazarett, and later was to become a leading figure in the revolt. Miete and Mentz were the brutal German killers at the Lazarett.

Alongside the ramp were two large barracks where the victim’s belongings were sorted and stored. North of these storerooms was the station square. East of this section was a fenced-in area called variously the undressing square (Entkleidungsplatz), deportation square, or transport square. It was at this place the men were separated from the women and children. Two large barracks were situated here. The northern barrack was utilised by women to undress, as well as for the cutting of their hair by barbers who worked behind a partition wall at the end of the barrack. The southern barrack, was used in the early phase of the camp’s existence for male prisoner’s sleeping quarters. Later it was used as a storage depot for goods. Male victims undressed in the open air between the barracks.

The extermination area, approximately 200m by 250m, where the mass murders were carried out, was in the southeastern part of the camp. This area was completely isolated from the rest of the camp by a barbed wire fence camouflaged with tree branches, as well as a high earthen mound, all of which prevented observation from the outside. The gas chambers were located inside the extermination area in a long brick building. During the camp’s initial phase there were three gas chambers, each 4m by 4m, and 2.6m high, similar to the first gas chambers constructed at Sobibor. A room attached to the building contained a motor, which introduced the poisonous carbon monoxide gas through pipes into the chambers. The room also contained a generator, which supplied electricity to the entire camp.

The entrance doors to the old gas chambers opened onto a wooden corridor at the front of the building. Each of these doors was 1.8m high and 0.9m wide. The doors were hermetically sealed and locked from the outside. Inside the gas chambers, opposite each entrance door, was another door made of thick and strong wooden beams, 2.5m wide, and 1.8m high. These doors were also hermetically sealed and opened in a similar manner to modern garage doors, i.e. upwards. They were propped open with wooden beams while the bodies were removed. The walls of the gas chambers were partially covered with white tiles. Showerheads and piping criss-crossed the ceiling, all designed to maintain the illusion of an ordinary shower room. The piping actually served to carry the poison gas into the chambers.

The witness Jan Sulkowski, a Polish prisoner from the Treblinka l forced labour camp, who helped construct the death camp from 19 May 1942, recalled:

“SS-men said it was to be a bath. Only later on when the building was almost completed, I realised it was to be a gas chamber. What was indicative of this was a special door of thick steel insulated with rubber, twisted with a bolt and placed in an iron frame, and also the fact that in one of the building compartments, an engine was installed from which 3 iron pipes led through the roof to the 3 remaining parts of the building.

A specialist from Berlin came to put tiles inside and he told me that he had already built such chambers elsewhere”.

East of the gas chambers and close by them were huge ditches for burying the corpses. A number of these ditches were approximately 50m long, 25m wide, and 10m deep. The ditches were dug by an excavator brought from the quarry at the Treblinka 1 forced labour camp. Initially the bodies were brought from the gas chambers to the ditches by trolleys pushed by the Jewish Sonderkommando on a narrow gauge railway. However, this system proved to be impractical and was replaced by the carrying of corpses on stretchers.

Southeast of the gas chambers were two combined barracks enclosed by a barbed wire fence, erected as quarters for the upper camp Sonderkommando. The barracks included a kitchen, a toilet, and later a laundry. A watchtower and guardroom was built in the centre of the extermination area.

The undressing square in the lower camp was connected to the extermination area by the Schlauch (the “Tube”). This pathway, 80-90 m long and approximately 4m wide, was enclosed with 2m high camouflaged barbed wire fences. The Germans cynically called it the “Himmelfahrtstrasse” – The Road to Heaven”. It commenced behind the women’s undressing barrack and continued east and then south to the gas chambers. The naked Jews were driven along this path to the building containing the gas chambers by Germans and Ukrainians wielding whips.

The SS living area in the northwestern part of the camp comprised living quarters for the SS and Ukrainian personnel, who were housed in the Max Biala Kaserne, as well as the Kommandantur, offices, an infirmary, stores and workshops. At Christmas 1942, Stangl ordered the construction of a fake railway station. A wooden clock with painted numerals permanently indicating 6 o’clock, signs reading `ticket window’, `cashier’, `station-master’ and various timetables and arrows falsely indicating train connections `To Warsaw -To Bialystok – To Wolkowysk’ were displayed, as well as a signboard indicating to deportees that they had arrived at a station called `Obermajdan’.

In early 1943 the SS constructed a zoo and a relaxation area, complete with tables and sunshades, and also built a more elaborate main gate situated near the railroad entrance. The gate consisted of two wooden pillars each decorated with a metal flower, and crowned by a small roof which rested on the pillars; it resembled a Polish country-style gate. At night floodlights lit the entrance, Ukrainian and SS-men were posted at the main gate and at the guardhouse, which was built in Tyrolean style. At the entrance a sign read “SS Sonderkommando Treblinka”.

The extermination process explained:

The incoming deportation trains generally consisted of 50-60 cattle wagons containing six to seven thousand people in total. After passing through Malkinia-Gora junction the trains crossed the Bug River, and came to a halt at the Treblinka village station. The station-master, named Franciszek Zabecki, was a member of the Polish underground, and a key observer of the events of 1942 and 1943.

Each transport was divided into sections of twenty wagons, and was pushed by a locomotive, driven by Emmerich and Klinzmann, officials of the Reichsbahn / Ostbahn, onto the siding leading to the camp. The remaining wagons waited at the station. As each section of the transport was about to enter the camp, SS and Ukrainian men took up position on the camp’s railway platform and in the reception area. When the wagons stopped the doors were opened one at a time by the Blue Kommando and the SS men and Ukrainians ordered the Jews to leave the wagons. Oscar Strawczynski recalled:

“We run out as fast as we can to avoid the whips lashing overhead, and find ourselves on a long narrow platform, crowded to capacity. All familiar faces – neighbours and acquaintances. The dust so tremendous, it obscures the sunlight. A smell of charred flesh stifles the breath. Unwittingly, I catch a glimpse of the mountains of clothing, shoes, bedding and of all kinds of wares that can be seen over the fence. But there is no time to think – the dense mass of people is pushed toward and jammed through a gate”.

An SS officer then announced to the arrivals, that they had arrived at a transit camp from which they would be sent on to various labour camps, but first they had to take a shower for hygienic reasons, and to have their clothes disinfected. Any money and valuables in their possession were to be handed over for safekeeping and would be returned to them after they had showered. Following this announcement the Jews were ordered to the undressing square.

At the entrance to the undressing square the men were ordered to the right for undressing, and the women and the children to the left. Supervised by the Red Kommando, this action had to be performed at running pace and was accompanied by shouting and beatings by the guards. After undressing, and in the case of the women, having their hair cut, the naked victims entered the “Tube” that led directly to the gas chambers. Many sources claim that the women and children were gassed first, whilst the naked men tidied up the yard first and then went to their deaths. Oscar Strawczynski again:

“But there, on that sorrowful transport square, there is no time for tears or feelings. I scarcely have time to hand my wife the carefully hidden blanket for the children. A brutal hand grips my shoulder and I am hurled to the other side of the square. I manage to stay with my gentle father. The place is packed with people. On one side are women with small children, on the opposite side, men, forced to kneel. In the middle there are SS –men, Ukrainians with weapons in their hands, as well as a group of about forty men with red armbands. These are Jews – the detachment of “Reds”. In Treblinka slang they are called “Chevra Kedusha” (Society for Last Rites).

Most prominent among all in the square is a German officer, a stout man with a short beard, mounted on a beautiful brown horse. He moves haughtily on his horse, in the middle of the square.

At a certain point he turns toward the kneeling men and shouts: “Craftsmen out”. A number of men step out. Most of them however, are sent back. Only a few are stood aside, where an SS-man makes a further selection, and groups the remaining men in threes. I am kneeling beside my father. My mind is completely blank. No feeling, not a thought. I do not even say a single word to my father.”

Once the victims were locked in the gas chambers, the motor was started and the carbon monoxide gas was pumped in. Within 20–30 minutes, all of the victims were dead. Their bodies were removed from the chambers and taken to the burial or cremation ditches. In the initial phase, a section of twenty wagons containing 2,000–3,000 people could be liquidated within 3-4 hours. Later, with experience, the Germans managed to reduce this time to an hour and a half. Even as the first batch of Jews was being murdered, the railway wagons in which they had been transported were cleared and cleaned. Some 50 prisoners undertook this task, after which the wagons were pulled out of the camp to make room for the next batch of deportees.

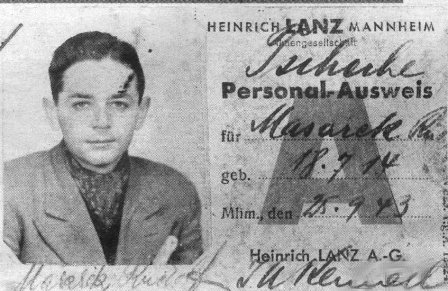

At this time, another team of approximately 50 prisoners collected the clothes and goods that had been kept in the undressing square and transferred them to the sorting square. Here a sorting command searched the belongings for money or valuables and sorted the clothes. This command was also responsible for removing the Jewish Stars from the clothing, and destroying identity cards and other documents the Germans considered to be of no value. Once sorted, the victim’s possessions were stored, and at the appropriate time were forwarded to the SS warehouses in Lublin.

200-300 prisoners, the Sonderkommando, were employed in the extermination area on such tasks as the removal of the corpses from the gas chambers, cleaning the chambers, extraction of the victim’s gold teeth and burial of the bodies. From winter 1942/43 corpses were cremated by the Sonderkommando instead of being buried.

As at Belzec and Sobibor death camps, the Germans soon realised that the capacity of the gas chambers needed to be increased in order to exterminate the number of Jews still alive. Between early September 1942 and the beginning of October 1942, Wirth and Stangl took the decision to build larger extermination facilities. In order to obtain the bricks necessary for the construction of the new chambers, the SS scoured the local area. Eventually an old glass factory chimney at Malkinia was demolished by the camp’s construction expert, Erwin Lambert, and the bricks were used to build the new extermination facilities.

The new gas chambers each measured 4m x 8m. The total area covered by the three old chambers was 48 square metres; the new gas chambers encompassed an area of 320 square metres. The new gas chambers were 2m in height, about 0.60m lower than the old chambers. This lowering in height reduced the amount of gas required to kill the victims. A central corridor ran along the length of the building, with 5 gas chambers on either side of the corridor. The entrance doors and body removal doors of the gas chambers were of a similar design to the old gas chambers. Alongside the doors was a small glass panel set in the wall, through which SS-men and Ukrainians could observe the interior of the chambers. The entrance to the Gas

Chamber was covered by a Jewish ceremonial curtain, taken from a synagogue, where it had been used as a covering for the Ark (Aron Kodesh). Either on the curtain or on the building was the Hebrew inscription “This is the Gateway to God. Righteous Men will pass through”. The gable over the entrance bore a large Star of David. To reach the opening of the building, the victims had to climb five wide steps, decorated on either side with potted plants.

The new gas chambers could exterminate a maximum of 3,800 people simultaneously; the old gas chambers had a maximum capacity of 600 people. Heinrich Matthes was the chief officer of the upper camp, assisted by Rum, Potzinger, Munzberger, Horn, Floss and others, including the Ukrainians Marchenko and Shaleyev. The extermination programme at Treblinka commenced on 23 July 1942. The first transports came from the Warsaw Ghetto, and by 21 September 1942, some 254,000 Jews from Warsaw itself and 112,000 Jews from other places in the Warsaw district had been murdered in Treblinka. Among the victims was Janusz Korczak, the noted director of a children’s orphanage in Warsaw. Transports arriving from Austria included relatives of Sigmund Freud.

By the winter of 1942-43, 337,000 Jews from the Radom district had been killed, as well as 35,000 from the Lublin district. In total an estimated 738,000 Jews from the Generalgouvernement and more than 107,000 from the Bialystok district were slaughtered between July 1942 and April 1943.

Jews from outside Poland were also murdered at Treblinka, 7,000 Jews from Slovakia, were killed in the summer and autumn of 1942. Between 5 and 25 October 1942, five transports brought 8,000 Jews from Theresienstadt (Terezin). Over 4,000 Jews from Thrace, formerly a part of Greece but now annexed to Bulgaria, arrived in the latter half of March 1943. 7,000 Macedonian Jews were murdered between March 1943 and April 1943. At least one transport of 2,800 Jews was dispatched from Salonika at the end of March 1943. 2,000 Romany Gypsies were also murdered in Treblinka death camp. The extermination programmed continued until April 1943, after which time only a few isolated transports arrived. Some included the survivors of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

During spring 1943, a savage typhus epidemic ravaged the Jewish prisoners. Hundreds of the infected were sedated, then executed at the Lazarett by August Miete, and Willi Mentz.

Several individual attempts to escape and acts of resistance occurred; for example, the killing of SS-man Max Biala by Meir Berliner on 11 September 1942. Dr Julian Chorazycki, one of the leaders of the planned revolt, was discovered by Franz to be in possession of a large sum of money. Chorazycki unsuccessfully attacked Franz, and then took poison in order to avoid betraying the revolt.

The main task now facing the SS was the elimination of the evidence of the crime. Following a visit of Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler in early March 1943, the order was issued to cremate the bodies. The mass graves were opened and the corpses were exhumed and burned on huge cremation grids, constructed from railway tracks, under the guidance of SS-Scharführer Floss.

With the cremation of the bodies nearing completion, a resistance group including Lageraltester Engineer Galewski, the aforementioned Dr Julian Chorazycki, Zelo Bloch, Zvi Kurland, and Dr Leichert was formed and plans for a revolt were formalised. Dates for an uprising were agreed and then postponed. When it was clear that the uprising could no longer be delayed, the revolt was set to take place on the 2 August 1943, at 5pm. Weapons were removed by the resistance from the SS armoury, and distributed. On the appointed day, as the time of the uprising grew near, SS-men Franz and Rottner, together with 16 Ukrainians, went for a swim in the nearby Bug River, thereby depleting the SS garrison.

When Kurt Kuttner, in charge of the lower camp, started beating a prisoner, the resistance leaders had no option but to fire a shot and start the revolt earlier than planned, as they were afraid the prisoner being beaten would reveal all.

The rebels possessing stolen weapons started the revolt at two minutes to four, opening fire on the camp guards. The petrol station exploded in a mass of flames thanks to Standa Lichtblau, who worked in the garage. Wooden barracks and fences were set ablaze, although the gas chambers were not damaged. The prisoners now tried to escape from the camp. They were fired at by the guards in the watchtowers, and many died, entangled in the barbed wire that was strung across the anti-tank obstacles.

Most, if not all of the leaders of the revolt were not successful in escaping from the camp. Galewski did taste freedom, but did not survive the brutal aftermath of the uprising. The inmates who did escape were pursued by the local police and security forces, including guards from the forced labour camp at Treblinka I. Railway guards, Ukrainians on horseback and members of the Gendarmarie, also joined in the pursuit. The fire brigade from Malkinia arrived to put out the burning fires in the camp itself.

Of the 1,000 Jewish prisoners were alive when the revolt took place, approximately 200 managed to break out. Only 60 of those who escaped were alive at the end of the war to tell the world about the horrors of Treblinka. Of the prisoners who remained in the camp after the uprising, some were killed on the spot, whilst the rest were forced to demolish the remaining structures and obliterate all traces of the camp’s murderous activities. Since the gas chambers had not been destroyed in the revolt, they continued to function and the last victims from Bialystok were gassed on 21 August 1943.

When this final gassing was completed, the camp area was ploughed over and trees were planted. The camp was turned into a farm, and a Ukrainian guard named Streibel was settled there with his family in order to protect the site from being plundered by the local population. After Streibel and his family left the site in 1944, the local population descended on the former camp site looking for gold and other valuables. Whilst doing this they discovered parts of decomposed bodies.

The remaining Jewish prisoners were either shot or transferred to the Sobibor death camp on 20 October 1943, via Siedlce and Chelm. On 17 November 1943, the last transport departed, carrying equipment from the camp. Parts of the barracks had already been sent to Dorohucza labour camp on 4 November 1943.

There have been many attempts to accurately calculate the number of victims of the Treblinka death camp. Since the Nazis destroyed most of the relevant data, it is doubtful if a definitive figure will ever be established. However, based upon the most recent research, it is estimated that a total approaching 900,000 Jews were murdered in the camp between July 1942 and August 1943.

Sources Encyclopaedia of The Holocaust Arad – Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka Hilberg – Sonderzuge Nach Auschwitz Donat – The Death Camp Treblinka Sereny – Into that Darkness Willenberg – Surviving Treblinka Glazar – Trap with a Green Fence Chrostowski – Extermination Camp Treblinka

Photos Sources:

Kurt Franz Album USHMM Private Collections

Copyright: Chris Webb & Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T 2007

|