Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Aktion Reinhard A-R Leadership

A-R Articles

Action Erntefest Modern Research | ||

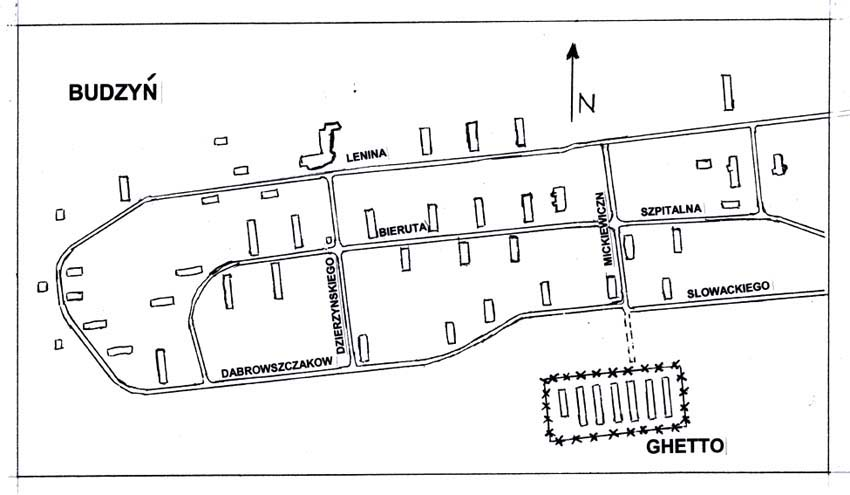

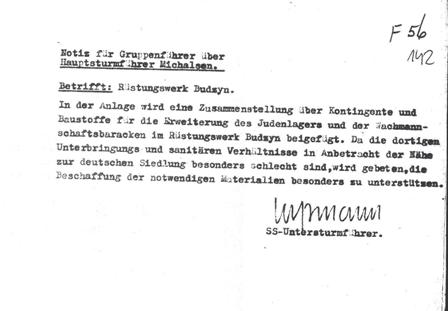

Budzyn Labour Camp The Budzyn Labour camp was situated 5km / 3 miles northwest of the town of Krasnik. A military – industrial complex including an aircraft factory was established on the premises of a former munitions factory in 1937 -38. Following the German invasion of Poland, the complex was taken over by the Herman Goring Werke, a huge industrial concern, operating steel works, mines and other heavy industries throughout occupied Europe. The aircraft factory was operated by the Heinkel Company – Heinkel Flugzeugwerke. Near this establishment a slave – labour camp for Jews, in which eventually nearly 3000 Jewish prisoners were interned, was established in the autumn of 1942. 500 Jews were brought to the Budzyn labour camp in November 1942 these came from mainly from Krasnik and other adjacent towns and villages. The local ghetto at Krasnik was liquidated in November 1942 where the majority of the Jews were deported to the Belzec death camp, others were shot at the Krasnik Jewish cemetery or selected to work in Budzyn. Shortly after that a further 400 Jewish Polish Prisoners of War were brought from the Konskowola camp and the Lipowa Street camp in Lublin. From its inception in Budzyn Jewish Prisoners of War performed as functionaries and they retained the uniforms of the Polish army. At the beginning of 1943 the last Jews from the Belzyce ghetto, including women and children were also sent to Budzyn. Among this group were German Jews deported to Belzyce from Stettin in 1940 and from Leipzig in 1942. During the crushing of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising 800 Jews arrived from Warsaw at the end of April 1943 and the beginning of May 1943. Included in the above were 150 Jewish workers who had worked at the Okecie Airfield in Warsaw prior to the uprising in the ghetto. The final group of Jewish prisoners were sent to Budzyn on 10 July 1943 from Hrubieszow following the liquidation of the ghetto there. By mid-1943 the camp population had risen to approximately 3000, including 300 women and children.

Thanks to a Polish Home Army report (AK – Armia Krajowa) from Krasnik dated 15 March 1944 the precise number of inmates are known – 2457 Jews including 319 women. This figure is lower than the 1943 amount as a result of executions – the prisoners worked in the aircraft factories, in construction and general services. Leo Freitag provided a statement in 1968 in New York regarding Budzyn: “At the end of 1941 or the beginning of 1942 I went from Krasnik to KZ Budzyn. When I am told that the Budzyn camp was, at the beginning a Zwangsarbeitslager and then later a KZ, then I think I came there at the time it was a labour camp. That was the time when the Jews were taken out of Krasnik. We wore civilian clothing – only later did we get the striped clothing. The time of the change-over I can no longer remember exactly. It was either 1942 or 1943. I worked in Budzyn – as in all the camps I was in – as a joiner. During the construction of the factory I made, for example, tables and doors, everything expected of a joiner. The head of the joinery workshop was an ethnic German by the name of Karl. He was a civilian. Of the guard detachment I remember especially well Feix and Hantke. There was also one with a name which sounded like Acker or Ackerman. When the name Axmann is mentioned to me, then I am sure this is the man I am thinking of. When the name Josef Leipold is mentioned to me, then I can now remember him very clearly. He was I believe an SS- Quatermaster Sergeant. He was the last commandant of the camp. He went with us to Brunnlitz. Not all the other guards came with us. In the course of time the younger SS- men were replaced by older SS-people and invalids. The younger ones went to the Front – this was not in connection with the changeover from a ZAL to a KZ. The names mentioned to me of Wilhelm Kleist and Friedrich Buschbaum, mean nothing to me. When I was told that the conditions in the KZ were an improvement compared to the ZAL, then I must say to that, that the conditions in many respects were better in many ways, and in many others worse. Before civilians also had power over us and could kill prisoners. Afterwards, only the SS could kill prisoners. Once, we came back from work in the evening and had to fall –in for roll call. A man was called out on whom money had been found. All the prisoners had to beat him, then he was finished off with a bullet by the SS. The exact date of this incident I cannot remember. I don’t know if at that time we already wore the striped clothing. When asked who carried out this roll call, I think that the camp commandant was present. The commandant at this time was Feix. On another occasion, some prisoners were given an axe on their work-free Sunday and led into a small wood to cut down saplings. In my view this was only a pretext for killing the prisoners. Anyway 2 people were shot. I think that Feix and Axmann led this operation. I also remember well that one morning when we came out of the barracks, a German Jew was hanged on the roll call square. He had been an officer in the German army. The SS had hanged him. (See the testimony by Dr David Wdowinski). Another time 2 Jews were drowned in the latrines because they had bought civilian jackets from Poles. At another incident 5 -7 prisoners had to spend the night outside the locked barracks. The next morning we found them dead. They had been shot by the guards. 2 of the victims were the Davidson brothers who came from Krasnik. I remember that once when we returned from work, the old, sick and the children were no longer in the camp. We were told that they were taken out of the camp in a railway wagon – and had been killed. With me in Budzyn camp were my brothers Max and Harry Freitag, and my brother- in- law Louis Adler, who all live here in New York”. Abraham Dichter from Hrubieszow gave a report on Budzyn: The boys arrived at Budzyn at the beginning of 1943. Here they again met many friends and acquaintances from Hrubieszow. Abraham was fortunate enough to get a job in the kitchen carrying coal. This was one of the most sort after jobs in the camp as it meant proximity to food. The camp was run by a Jewish Prisoner of War Stockmann under SS- Lagerkommandant Feix. As the camp had originally been established for Poles of Jewish origin who were POW’s, these had all the best jobs. The new arrivals, as a rule, were slaves in the camp. Feix was a sadist who would whip, shoot or torture for his amusement. Only curiously, he had a soft spot for German Jews and would try to give them an easier time. Abraham remembers an occasion when 2 prisoners tried to escape by digging a tunnel under the barracks into the woods. Unfortunately the tunnel caved in under the barbed wire. One of the escapees was shot, the other captured. The latter was hung up for days by his hands, which he could never use again after this torture. The night after the attempt all the prisoners had to stand in the snow for a whole night. The daily routine at Budzyn was as follows:

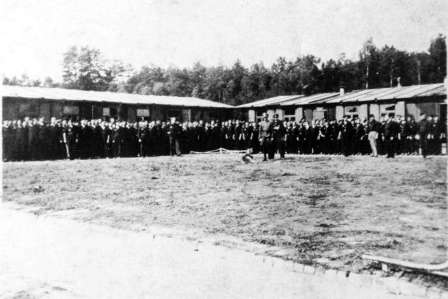

An incident Abraham remembers with amusement was another escape attempt. At the time Abraham and several other prisoners were working in the kitchen. The German guards, furious about the attempt, turned their machine-guns onto the camp and started shooting it up. As the kitchen was one of the few places where the lights were still on, it became an immediate target for the guns. Abraham and the others hid in the huge copper kettles, impenetrable by bullets, which were used to make the daily cabbage soup – and saved their lives. Although they might easily all have been killed, this incident was welcomed by Abraham, for it broke the terrible monotony of camp life. Five prisoners were killed on this occasion. During 1943, a new camp was built nearer the aircraft factory and the prisoners were transferred to this. The new camp was a KZ and all the prisoners were issued with regulation striped uniform – except Stockmann, who was allowed to keep his Polish uniform. Conditions were slightly better than at the previous camp, partly because no Ukrainian guards were used, as some had recently deserted, and the Ukrainians had been much worse than the Germans themselves, committing acts of the most appalling cruelty. In the middle of 1943 Abraham Dichter went with a large transport to Majdanek Concentration camp. At the Adolf Eichmann trial a survivor of Budzyn Dr David Wdowinski described how he had been deported to Majdanek in May 1943 after being captured during the Warsaw ghetto uprising, A few days later he was transferred to Budzyn, together with 806 other Jews. He described their arrival at Budzyn: “Turning, we sighted Camp Budzyn about a quarter-mile distant, this was a genuine SS camp, a fenced-in rectangle flanked by four towers, one at each corner. Looking out from the top of these were armed Ukrainian guards manning machine-guns. Directly ahead was the entrance gate. A guard house on our right, across the road from a cluster of young pines and brush, was the last landmark as we stood outside the gates. Beyond the barbed wire stood a row of barracks backed by a large open square. No bigger than a football field the complex was surrounded by a belt of open country surrounded by pinewoods. The commandant Feix told us to stand in two rows. Afterwards he went up to one of the Jews and told him to leave the rank and ordered him to undress. He then began undressing, he removed his overcoat and Feix started shouting “ Hurry up – undress completely”. This went on until he was altogether naked and then he drew a revolver and killed this Jew and said “This is what will happen to each one of you, if you do not hand over everything you have, and this is only an example”. He demanded gold, silver, good clothes, suitcases and so on. On the same day, he saw a man of advanced age, an old man and his first words were “You old dog – are you still alive?”

And he ordered the Ukrainians to shoot him and kill him – and he went off. Then we surrounded the old man and the Ukrainians were unable to find him. By chance the commandant came back to the camp half an hour or an hour later and saw the old man – he drew his revolver and shot him. He was a very popular doctor from Warsaw very much loved by the Jews of Warsaw – Dr Pupko. He was well- known, firstly because he was an Orthodox Jew, he prayed every day with his phylacteries and prayer shawl. He would not write any prescriptions on the Sabbath and apart from that, he was known and loved, for he had done a great deal as a doctor for the poor Jews and had attended to them without payment. Wdowinski related another incident involving a prisoner named Bitter, who had been discovered with money on his person. Feix had beaten him and then commanded that Bitter should be hanged. But the rope broke. Feix decided it was not necessary to hang Bitter again and not wishing to waste a bullet on a Jew, ordered that his fellow Jews would kill Bitter. A roll-call was ordered. Each of the 2000 Jews was given a stick and forced to beat Bitter to death. A decree issued by Oswald Pohl, head of WVHA on 2 September 1943 announced that with effect from 1 November 1943 the Lublin labour camps would be subordinated to the Ministry of Munitions and Armaments. In order to prevent this from happening and thereby losing control of these valuable resources, the SS declared that the labour camps were branches of Majdanek on 13 February 1944. Budzyn officially became a concentration camp and became a sub-camp of Majdanek on 13 February 1944. Budzyn’s Jewish workers at the Heinkel factory were spared the fate of the other Jewish workers in the Lublin area, when all the Jewish workers in the labour camps were liquidated during the Aktion Erntefest in November 1943. But even at Budzyn most elderly Jews had been selected and deported to Majdanek to their deaths. One of the Jewish cleaners in the camp Jacob Katz saved the lives of seven elderly Jews at this time by hiding them under mattresses. After Budzyn was subordinated to Majdanek the living conditions in the camp improved. All prisoners were removed from the old camp to the new barracks closer to the factory. They had to wear prisoner clothing from Majdanek they received numbers and better food. All executions which were fewer in number during 1944 had to be conducted in accordance with concentration camp regulations. Whilst no paradise, conditions at Budzyn were more favourable than other labour camps, and the efforts of Noah Stockmann from Brest-LItovsk, the camp elder, who managed to persuade the camp administration to allow the Passover to be celebrated in the camp in the spring of 1944. In May 1944 as the Soviet army began to approach the Lublin district, the factory installations and some of the workforce were transferred to the salt mine in Weiliczka. Other prisoners were dispersed to camps at Skarzysko- Kamienna, Starachowice, Mielec, Ostrowiec and Majdanek. Among those transferred to Mielec was Manfred Heyman, born in Stettin and deported there to the Belzyce ghetto in February 1940. He had been sent to Budzyn aged 14 years old. He was transferred again to another aircraft factory near the Flossenburg concentration camp. He survived a death march from Flossenburg, and was liberated by American troops on 29 April 1945. After the war he settled in London, England. The first commandant of Budzyn was SS-Oberscharfuhrer Otto Hantke, he was succeeded by SS- Oberscharfuhrer Heinrich Stoschek. Before taking up his position in Budzyn Hantke had been in the Lipowa Street Camp in Lublin, and he was sent to Krasnik personally by Odilo Globocnik, SSPF Lublin, as a “good organiser”. Hantke was responsible for the selection during the final liquidation of the Krasnik ghetto. He personally selected at Budzyn those who were fit, those who were sick he selected to be deported to the Belzec death camp. This selection was was organised in accordance with an order from Christian Wirth, the Inspector of the “Aktion Reinhard” murder programme. After the war Otto Hantke was tried in Hamburg in 1974 and he was sentenced to life imprisonment, the deputy commandant Wilhelm Kleist was living in 1968 in the “Railway Hotel” in Homburg, Krs, Stade. The next and most brutal commander of Budzyn was SS-Oberscharfuhrer Reinhold Feix from December 1942 until August 1943. Feix came to Budzyn after service in the Belzec death camp. Feix was replaced by Otto Mohr, who was only commandant for a short time, and in the late summer of 1943 he was replaced by SS- Oberscharfuhrer Tauscher, who also had served at Belzec death camp. Tauscher was replaced by an SS – NCO Frank. Whilst he was not in charge for very long Frank ruthlessly suppressed a mass escape attempt in the winter of 1943. The final commandant was SS-Obersturmfuhrer Josef Leipold, who shot himself in the foot to avoid a possible transfer to front-line service. Sources:

Encyclopaedia of the Holocaust – Macmillan Publishing Company New York 1990 The Destruction of the European Jews by Raul Hilberg – published by Yale University Press, New Haven 2003 The Hoocaust by Sir Martin Gilbert –published by William Collins London 1986 The Boys – Triumph over Adversity by Sir Martin Gilbert published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson London 1996 Majdanek – The Concentration Camp in Lublin by Josef Marszalek – published by Interpress Warsaw 1986 Obozy pracy w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie w latach 1939 -1945 – The Work Camps in the Generalgouvernement in the years 1939 -45 – Lublin 1998. Iron Furnace – A Holocaust Survivors Story by George Topas – published by the University Press of Kentucky 1990. A Brush with Death. An Artist in the Death Camps by Morris Wyszogrod –New York 1999 I Shall Live – Surviving the Holocaust 1939 -45 – published by Oxford University Press 1988 Archives of the Majdanek State Museum – Collection of Jewish Testimonies Holocaust Historical Society

Copyright SJ – H.E.A.R.T 2007

|