Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Ghettos

Introduction to the Ghettos of the Holocaust

Jewish Ghettos The Judenrat Judenrat Leaders Prominent Jews

| ||||

Bialystok Ghetto

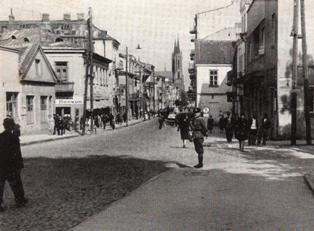

The city of Bialystok is situated in North-Eastern Poland, 188 km from Warsaw and 54 km from the border with Belarus. In common with the region named after it, the city had fallen under the control of many different countries in the course of its history. Bialystok became part of Prussia in 1795 before being annexed to Russia in 1807. In 1921, following the cessation of hostilities between Poland and the Soviet Union, the city was incorporated into the state of Poland.

The 1931 census revealed a total population in excess of 91,000, of whom nearly 40,000, or 43% were Jewish. On the outbreak of war on 1 September 1939, the Jewish population of Bialystok had risen to approximately 50,000.

Following the outbreak of war between Germany and the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, the Germans re-occupied Bialystok on 27 June. By this time, because of an influx of refugees from German-occupied Poland, the Jewish population of the city and surrounding district had swollen to about 60,000.

On the morning of the German entry into the city, a day which was to become known as "Red Friday" by the Jewish community, Order Police Battalion 309 gathered in the Jewish quarter around the Great Synagogue. Armed with automatic pistols and hand grenades, the Germans began killing Jews in the streets and houses in the area. At least 700 Jews had been locked into the synagogue, which had then been set on fire. The Nazis forced further victims to push one another into the blazing building. Those resisting were shot. On that first day, 2,000 - 2,200 Jews were killed.

Within the first two weeks of the German occupation, the Einsatzkommando 9 had murdered a further 4,000 Jews in an open field near Pietraszek. In the early days of German occupation the city had received visits from Heinrich Himmler, on 8 July, as well as from Adolf Eichmann, acting on the instructions of Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller. These tours of inspection, which included other recently conquered cities and towns, were intended to assess the impact of the first wave of Einsatzkommando activities.

Two days after the occupation, the military commander summoned Bialystoks’s chief rabbi, Dr Gedaliah Rosenmann, and the chairman of the Jewish Community Council, Efraim Barasz, ordering them to form a Judenrat. Initially formed with 12 members, all public figures, a month later a new Judenrat, twice the size of its predecessor was formed, with Barasz as its head.

On 1 August 1941 a ghetto was established in two small areas divided by the Biala River. The ghetto was surrounded by a wooden fence and barbed wire. As in other ghettos, the space allotted was totally insufficient for the number of inhabitants; two or three families were squeezed into a single tiny room. Until 15 August 1941, Bialystok was under military rule; from that date it became a quasi-incorporated territory of the Reich attached to East Prussia, under the civilian administration of Erich Koch in his capacity of Oberpräsident of East Prussia. A decree ordering all Jews to be registered, to wear yellow badges on their chest and back, together with a host of other discriminatory measures was introduced. All Jewish property outside the designated ghetto area was confiscated.

Food supplies were to be restricted to that which was "surplus" to local requirements. And all able-bodied Jews between the ages of 15 - 65 were to be subject to forced labour. Between 18 and 21 September 1941, 4,500 sick, unskilled and unemployed Jews were transferred to the ghetto at Pruzhany, 100 km south of Bialystok. Most of them were killed when that ghetto was liquidated in late January 1943.

As in other ghettos, the smuggling of food was the only way to avoid starvation on a massive scale. In small, secret workshops, goods were produced and exchanged for food with those living outside of the ghetto. In order to increase the availability of food, the Judenrat converted the sites of destroyed buildings within the ghetto into fruit and vegetable gardens. The Judenrat itself became a major employer; more than 2,000 people worked in various departments: hospitals, pharmacies, schools, a law court and other institutions. A Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst (Jewish police force) of 200 men was also organised.

Throughout 1942, the various factions of the Jewish youth movements had inched their way towards creating a unified front with a view to waging an armed struggle against the Germans. Agreement was finally reached in August 1942 and the first united underground, named "Bloc No.1" or "Front A", consisting of Communists, the Socialist "Bundists" and the Zionist "Ha-Shomer ha-Tsa’ir" was formed under the command of Edek Borak.

In November 1942 Mordechai Tenenbaum (Josef Tamaroff) arrived in Bialystok from the Warsaw Ghetto to bolster the resistance and "Bloc No.2" came into being, uniting all the remaining movements. On Tenenbaum’s initiative, supported by Barasz, a secret archive was established. Hidden outside of the ghetto, the documents it contained constitute an invaluable record of the ghetto’s existence. Barasz also made substantial sums of money available to Tenenbaum for the procurement of arms from the Polish underground Armia Krajowa (Home Army), but without success.

On 11 October 1942, by which time knowledge of Aktion Reinhard was sensed, if scarcely believed, Barasz addressed fellow Council members and the heads of ghetto workshops, saying: "It is imperative that we find means to postpone the danger, or at least reduce its scope."

The reprieve was short. Between 5 and 12 February 1943, an Aktion was conducted in the ghetto, in the course of which, 2,000 Jews were shot and a further 10,000 deported to Treblinka in 5 transports. On 19 February, at a conference held in Bialystok about the continuation of the deportations, it was announced that for economic reasons the Bialystok ghetto, with its remaining 30,000 inhabitants, would be left intact until the end of the war. But this was not to be.

Despite the continuing protests of the military and civilian employers of Jewish labour, in the summer of 1943, Himmler ordered the immediate liquidation of the ghetto. Since he no longer considered the local German authorities reliable, he entrusted the mission to the Aktion Reinhard staff and placed Odilo Globocnik in overall charge. Globocnik sent Georg Michalsen to oversee this task. German police, SS units and Ukrainian auxiliaries surrounded the ghetto on the night of 15 - 16 August 1943. Barasz was summoned by the Gestapo and informed that the ghetto inhabitants were going to be moved to Lublin. The ghetto awoke to find the Judenrat’s announcement of the deportation posted on the walls. As tens of thousands of Jews made their way to the assembly point on Jurowiecka Street - the underground rose in revolt. This was not the first act of resistance in Bialystok.

At the time of the deportations in February 1943, "Bloc No.1" had been activated and suffered many casualties in a vain attempt at armed resistance. Borak was among those captured and transported to Treblinka for extermination. But now "Bloc No.1" and "Bloc No.2", united since July 1943, began a desperate armed struggle. At 10 a.m. the various cells of the underground took up their positions and were issued with arms. The plan was to break out of the ghetto at the Smolna Street fence and escape to the forest. For the ensuing five days the poorly armed and heavily outnumbered members of the resistance fought against overwhelming German firepower, including armoured cars and tanks. Unable to break out of the ghetto, the fighters retreated into a bunker at Chmielna Street, which the Germans discovered on 19 August. All but one of the 72 fighters in the bunker was shot.

The next day as the last resistance positions fell, Tenenbaum and Daniel Moskowicz who had jointly led the uprising, died, probably by their own hand. Much has rightly been written about the heroic and doomed Warsaw Ghetto uprising, yet scant attention has been paid to the equally heroic and doomed Jewish resistance in Bialystok.

The deportations began on 18 August and continued for 3 days. 7,600 Jews were transported to Treblinka; thousands more were sent to Majdanek, where a selection took place. Those found fit were taken to Poniatowa, Blizyn or Auschwitz. More than 1,200 children between 6 and 15 were deported to Terezin (Theresienstadt) on 23 August. Many died there. The sick were taken to the Small Fortress section of the ghetto and beaten to death.

A few weeks later, the surviving children were deported again, this time to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where all of them were gassed on 7 October, together with the 53 adults who had volunteered to accompany them. In Bialystok itself a "Small Ghetto" was left, containing 2,000 Jews. After three weeks, it too was liquidated and its occupants sent to Majdanek. Amongst them were Barasz and Rosenmann, who, together with the remnants of the Bialystok Jews, were murdered there on 3 November 1943 in the so-called Aktion Erntefest. Three pits in Augustow contained 2,100 bodies. Other burial pits were opened in the vicinity of Grodno, near Staraya Krepost, at Novoshilovki, Kidl, and at Golnino near Lomza. By the time they managed their escape from the command on 15 May 1944, Edelman and Amiel were 2 of only 9 survivors of the original group.

Small numbers of armed men had managed to escape from the ghetto in December 1942. By the time of the uprising in the summer of 1943, 150 fighters from the Bialystok ghetto had joined the partisans. They harassed the Germans in the region until the liberation of Bialystok by the Red Army on 27 July 1944. By the war’s end approximately 300 - 400 Bialystok Jews had survived, either with the partisans, in German camps or in hiding on the "Aryan" side of the city.

The city’s post-war Jewish inhabitants peaked at little more than 1,000, before gradually dwindling away. Today, out of a population of 350,000, only a small number are Jewish. In October 1949, Fritz Gustav Friedl, commander of the Gestapo in Bialystok, stood trial in the city for war crimes committed there and in the nearby town of Zabludow.

A number of trials of individual’s accused of crimes in Bialystok were held in West Germany. In the main, these were of members of Einsatzgruppen or Police Battalions. Those found guilty generally received modest sentences.

Many were acquitted.

Private Collections Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, 1990.

Copyright I. Jones H.E.A.R.T 2007

|