Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Ghettos

Introduction to the Ghettos of the Holocaust

Jewish Ghettos The Judenrat Judenrat Leaders Prominent Jews

| ||

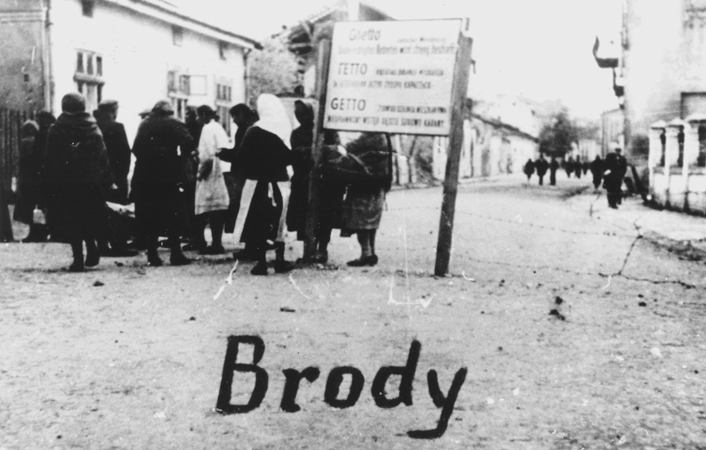

The Ghetto at Brody

Brody a town in the Lvov Oblast(district) Ukrainian SSR. Founded in the sixteenth century, Brody was under Polish rule in the period from 1918 to 1939, and was annexed to the Soviet Union in September of that year, 9000 Jews lived there in 1939.

It was one of the important Jewish communities in Galicia and for many years Jews constituted a majority of the population. Brody was well known on the one hand it was a renowned Hassidic centre, yet at the same time at the beginning of the 19th Century Brody also became one of the first locations of the Haskala (Jewish Enlightenment) in the province.

The prominent Jewish – Austrian novelist Joseph Roth came from Brody. The town itself was also well- known from the 18th Century when it became a major trading place, and in the 19th Century because of its location close to the Russian border, many Jewish refugees passed through Brody fleeing Russian pogroms.

From September 1939 until 1 July 1941 the town was under Soviet occupation, during this period some Jews collaborated with the Soviets. Some wealthy residents were arrested and deported to Siberia.

On 1 July 1941, the Germans occupied the town and lost no time in issuing anti-Jewish decrees, the Jews were ordered to wear an armband with the Star of David and to make punitive payments, they were subject to forced labour and their movements were restricted.

On 15 July 1941, a group of 250 intellectuals were summoned to the local Gestapo, where they were subjected to two days of torture and then murdered in ditches adjoining the Jewish cemetery.

On the day following the executions, the first Jewish Council (Judenrat) was established from among the Jewish intelligentsia who survived the previous day’s slaughter. The first president of the Judenrat was Dr Bloch, who before the outbreak of the Second World War had been a director of a local bank.

According to testimonies of survivors the first members of the Judenrat were decent, but later the local Gestapo replaced many members and quickly the Judenrat became simply a pliant tool for implementing German policy.

Together with German and Ukrainians many members of the Judenrat, as well as members of the Jewish police force, participated in the plunder of Jewish property.

The German civil administration ordered the payment of contributions by the Jews. Apart from money and valuables the Jews had to supply the Germans with furniture, clothes, shoes, linen and coffee.

The Judenrat was also ordered to supply hundreds of Jews daily for work on bridge repairs, on road building and in military camps. By August, Jewish property was being plundered on a large scale by both Germans and Ukrainians.

In December 1941, the Germans began stopping Jewish youths in the street, and transporting them to labour camps that had been established in the area. These camps were located at Jaktorow, Sasow, and Laski. Jewish women worked mainly in manors near the town – when rumours spread about impending deportations, some Jews paid large sums of money to acquire work-cards. At the same time some Jews began to construct shelters and hiding places in their homes.

In the first half of 1942 about 1,500 Jews were imprisoned in these camps. Their number dwindled sharply in the second half of 1942 and the beginning of the following year, owing to the high death rate caused by mistreatment, hard labour, starvation and disease.

During the summer of 1942 the Judenrat on its own initiative, launched an effort to find jobs in areas that were considered vital to the German economy, in the hope that this would give protection, at least to some degree, from deportation to the labour camps.

On 19 September 1942 Germans, including members of the Civil Administration under the command of Landkommissar Weiss,Ukrainian police, Ukrainian and Polish civilians, arrested Jews on the street or dragged them out of their houses and hiding places.

The Jews were gathered on the market square and from there were led to the waiting train, which took them to Belzec death camp. When this “Aktion” was over, 2,000 Jews were deported to the Belzec death camp, while 300 were killed on the spot.

Among the Germans in Brody there was one family who tried to aid the Jews. Liselotte Hassenstein and her husband Otto, who worked in the Forest Administration, were very active during the “Aktionen” in helping the Jews.

Otto Hassenstein saved many Jews by assigning them to work in the forest. He told everyone:

“Whoever works for me needs to be treated honestly, no matter if they are a Jew, or Pole or a German.” Of course, this work in the forest was a temporary reprieve, but still it was of great value during the deportations.

Liselotte was arrested by the Gestapo in 1943 when somebody denounced her for sheltering a Jewess in their attic. The woman had jumped off a train destined for the death camp. During the “Aktionen” in Brody Liselotte had frequently hidden Jews in her attic.

Liselotte Hassenstein was taken to Lvov (Lemberg) and was sentenced to death, a sentence that was later reduced to two years imprisonment. She was temporarily released from prison because of poor health and was ultimately liberated by the Red Army at the end of the war.

During the autumn and winter of 1942, the German authorities brought into Brody the remnants of other Jewish communities in the area, such as those of Sokolovka, Lopatin, Olesko, and Radechov.

In December 1942 the Germans announced the establishment of a ghetto in Brody, and by 1 January 1943, some seven thousand people had been gathered there, most of them from the vicinity. In the ghetto Jews were not permitted to walk on the main street and they were only allowed to shop for one hour per day, between 10.00 am and 11.00 am. All Jewish shops were confiscated and handed over to Ukrainians.

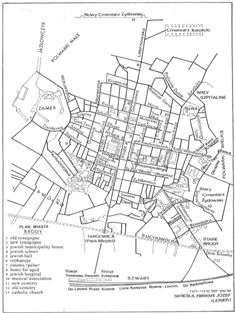

The inhabitants of the ghetto lived on two streets; Browarna and Slomiana, the office of the Judenrat was situated outside of the ghetto on Boznica Street. The ghetto was surrounded by barbed wire, and was extremely overcrowded.

Because contact between the Jews and non-Jews was prohibited, most of the Jews starved to death. Only those who worked outside the ghetto had the opportunity to smuggle into the ghetto some food.

Despite these efforts it was not enough and often or not some members of the Judenrat confiscated almost all of the smuggled food for themselves and their families. Officially, the daily portion of bread measured 80g.

There was a kitchen in the ghetto for poor people, but even there people had to pay for food, prices were low, but this was still out of reach for most people, only relatively wealthy individuals could afford to eat the soup cooked in the people’s kitchen.

1500 of the ghetto’s inhabitants died of starvation and typhus epidemics, and many others were shot by the Ukrainian police who guarded the ghetto perimeter, during the winter of 1942/43.

In March and April 1943 there were numerous “Aktionen” as a result of which thousands of people were rounded up and put to death in the neighbouring woods.

In the early months of 1943 a resistance group was organised in the ghetto. The leader of this group was Samuel Weiler. The resistance organisation made contact with the Polish underground, a unit of the Polish People’s Army from which they obtained several guns.

The Jews wanted to organise resistance in the event of the liquidation of the ghetto, some of the members of the group decided to escape to the forest prior to the liquidation. In addition, other Jews who were not connected with the resistance decided to escape from the ghetto in the certain knowledge that the next “Aktion” would lead to the final liquidation of the Brody ghetto.

In the Pianica forest a so-called “family camp” had been established, where 80 – 200 Jews from Brody sought refuge, armed with weapons supplied by the Polish underground.

The final liquidation of the ghetto took place on 21 May 1943, during which members of the Jewish underground organisation opened fire on the Ukrainian policemen and Germans. Several Ukrainians were killed. The Germans retaliated by setting the houses in the ghetto on fire and many people perished in the flames.

Other ghetto inhabitants were executed on the streets or in the forests near the town, but in the chaos that ensued, many Jews escaped from the ghetto. Among the escapees were some members of the resistance, led by Weiler.

He survived the war in a partisan unit. Of the many people who tried to escape only a small number survived with the help of Poles and Ukrainians.

In this final deportation more than 3,000 inhabitants of the ghetto were probably sent to Sobibor death camp. From the entire pre-war Jewish population of 9,000 in Brody, only 88 people lived to see the Germans driven out, and subsequent liberation.

Encyclopaedia of the Holocaust, published by Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, 1990 The Holocaust – by Sir Martin Gilbert, published by Collins London 1986 Holocaust Historical Society USHMM NARA

Copyright Robert Kuwalek & Harald Neilsen H.E.A.R.T 2007

|