Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Ghettos

Introduction to the Ghettos of the Holocaust

Jewish Ghettos The Judenrat Judenrat Leaders Prominent Jews

| ||||||

The Ghetto at Kutno

Kutno is located 33 miles north of Lodz, and is roughly in the centre of Poland. A Jewish community existed in the mid 15th Century. A synagogue was built in 1766 and survived until 1939. In 1753, a fire destroyed the town including all documents of the Jewish community.

Therefore, not much is known of the history of Jewish community of Kutno until mid-18th century.

What is known is that the Jews were established in commercial activity, extending all the way to Germany and the Netherlands. The Jewish population in 1897 was 10,356 this was approximately 50% of the total population. The city enjoyed long years of success under the reigns of diligent and enlightened owners; it also struggled with crises following turbulent history of Poland and the disintegration of feudal structures.

Kutno was a centre of rabbinical learning and prominent personalities such as Nahum Sokolow and Sholem Asch studied at the Yeshiva. Asch was born in Kutno 1880 and immortalised the town in his works.

Zionist activity began in 1898 and most of the Zionist political parties and youth movements were founded prior to the First World War. A Yiddish school was founded in 1916 and this existed until 1935. The majority of the community was employed as salaried workers during the 19th Century and they increased proportionally during the next Century, mainly in the textile and food industries.

The income of Jewish shop owners and artisans was adversely effected by the boycott imposed by the Endecja Party between the two World Wars. Shortly after World War One a trade union was established by the Bund and a Jewish Labour union was organised while a Jewish merchants association was set up in 1932.

In the 1924 community council elections the Zionists won 50% of the seats and Jewish representatives were elected to the municipal council. A Jewish government elementary school opened in 1926 and two years later a school with Yiddish instruction opened its doors, one year earlier a University was opened.

Before the onset of the war, 8000 Jews were living in Kutno. Once the Germans entered Kutno on the 15 September 1939 Jewish males were rounded up and sent to forced labour camps in Piatek and a group of seventy to a prison camp in Leczyca.

Jews were persecuted daily and Jewish property was plundered, the Jewish synagogue was burned down, and only the walls remained. A Judenrat was established in November 1939 and on the 15 June 1940 8,000 Jews were incarcerated in the ghetto.

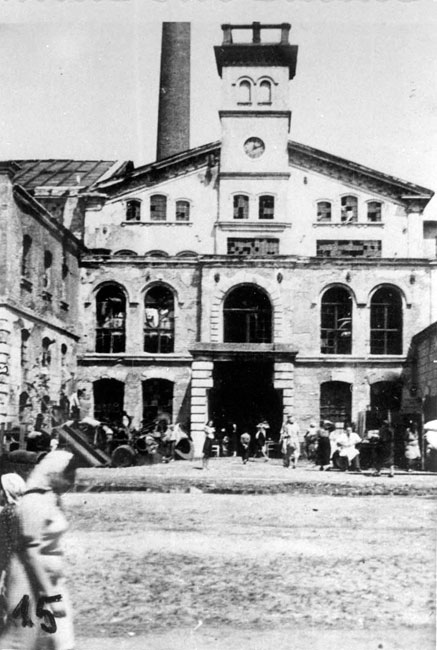

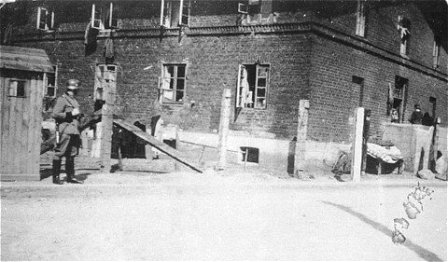

With the ghetto’s establishment, all the Jews were transferred to the grounds of the “Konstancja” sugar factory. The eviction was photographed by Franz Hansen, a Wehrmacht soldier posted there.

More than 7000 Jews were crammed into the grounds of the factory, several buildings of which had been bombed, forcing many of the new tenants to make outdoor living arrangements. The Germans surrounded the area with barbed wire and watchtowers.

By mans of the black market and smuggling, the ghetto prisoners managed to preserve a semblance of normality, apart from the terrible living conditions. However, from time to time epidemics broke out, and food was sometimes scarce.

On June 15 1940 eight thousand Jews were brutally deported to the ghetto, the old sugar factory and it’s five buildings. Sanitation and overcrowding was tragic, and food allowances were inadequate and a flourishing black market was created.

Litzmannstädter Zeitung (newspaper), Sunday, 22 September 1940

The Ghetto – a Place of Decay

The mayor introduced us to the Police Chief, Lieutenant Weißenborn, who invited us to visit the ghetto. We soon arrived at the gates of a half-dilapidated factory, which had not been entirely spared from the battles for Kutno. It was raining.

The factory site is a total mud bath. Even just entering the ghetto showed that the mayor was really not exaggerating when he referred to an unbelievably dirty rabble. We are used to all kinds of filth from the Litzmannstadt ghetto, but what we saw here surpassed everything we had previously encountered.

'Imagine if this was a German prisoner of war camp! In 14 days the place would be clean and orderly. But since they moved here in April, the Jews have not lifted a finger to make their living conditions in some way fit for human beings. On the contrary, the filth has increased significantly', explained Lieutenant Weißenborn.

In the yard we saw stalls made out of dilapidated fireplaces trading the most extraordinary things: food, half shoe soles, rusty nails and other such items. A community kitchen had also been set up so that the poor would not starve – but not on the initiative of the wealthier Jews! We cast a look inside. It stank of burnt onions. 'Pea soup' was apparently available. We wished them bon appétit!

Then we entered the factory. Seven and a half thousand Jews live here. As the Lieutenant said, this is not a camp where order prevails, but a pile of dirty cave dwellings. The Jews seem to feel at home here.

Some of them approached the Lieutenant and asked him for permission to go into town. Each of them had a different request. Permission was only granted in a few warranted cases.

"There are various jobs which are really suited to the Jews', said the Police Chief, 'and as long as there is good leadership we let them work relatively independently at the workplaces concerned. But most of them are lazy and prefer to hang around here.' We left the place of decay."

During the winters of 1940/41 and 1941/42 the German authorities deprived the ghetto of fuels, typhus and tuberculosis epidemics broke out, many died of disease, hunger and cold, whilst others committed suicide.

Benard Holcman was the Chairman of he Jewish Council (Judenrat) whilst the general opinion was that this council was extremely corrupt they did try to organise food supplies to the ghetto.

The liquidation of the ghetto commenced on the 19 March 1942, the Germans as a first measure murdered all the elderly inhabitants in the ghetto, the remainder, numbering some 6,000 were then selected according by alphabetical order to be deported by truck or by freight train from Kutno to the train station at Kolo.

From Kolo station the Jews were transferred by narrow gauge railway to Chelmno death camp where they were murdered in gas vans, for that final journey the Jews of Kutno were not allowed to take any luggage and they had to pay between 12 and 20 marks each for the journey.

An entry in the Chronicle of the Lodz ghetto for the end of April 1942 read:

“Sewing machines have arrived in the ghetto in great quantities via Balut Market over the last few days. On the basis of evidence in the form of notes and printed matter found in the drawers of these machines, one may conclude that they were sent here from small towns in Kolo and Kutno counties.”

Szlamek Bajler and Family

Monday 12th January 1942

“At 7am they brought us coffee and bread. Some of the men from Izbica – who had lately lived in Kutno- drank up all the coffee. The others got very annoyed and said we were already facing death and had to behave with dignity. It was decided to share out a little coffee to everyone in future.

At 8.30 we were already at work, at 9.30 the first gas van appeared.”

Another entry regarding Kutno was recorded as thus in the Chronicle of the Lodz ghetto;

Saturday 24 June 1944

“The ghetto is agitated because the railroad cars that carried off yesterday’s transport are already back at Radogoszcz station. People infer that the transport travelled only a short distance, and a wave of terror is spreading through the ghetto. People recall the frequent shuttle of transport cars and trains during the period of the great resettlement of 1942 and the alarming rumours of that time.

Reportedly, a note was found in one freight car indicating that the train went only as far as Kutno (33 miles north of Lodz) where the travellers were transferred to passenger cars.

The information has not been confirmed, no one has actually seen the note, so no conclusions can be drawn about the quick return of the cars. Perhaps further transportation is being staged in Kutno. It is hoped that we will son learn what is happening with these people.”

After the war, a few Jews bought ashes from Chelmno and buried them here. A monument was erected in the shape of a Star of David and inscribed in English and Hebrew to the victims of the Shoah.

It was a stylized metal plate and bore the following inscription:

"To the eternal memory of the Jewish victims of Nazi terror who lie in a fraternal grave. In your memory."

The monument was destroyed shortly afterwards by "unknown perpetrators". The last Jewish burial in the cemetery was in 1948.

Sources: The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life – Chief Editor Shmuel Spector, published by Yad Vashem 2001 The Chronicle of the Lodz Ghetto edited by Lucjan Dobroszycki, published by Yale University Press 1984 Chelmno Witnesses Speak, edited by Lucja Pawlicka- Nowak, published by The District Museum Konin 2004 Antisemitism - The Longest Hatred, Wistrich, Robert S, Thames Mandarin, London, 1992. Kutno / Judaica Kutno.pl / website

Copyright Chris Webb H.E.A.R.T 2009

|