Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Ghettos

Introduction to the Ghettos of the Holocaust

Jewish Ghettos The Judenrat Judenrat Leaders Prominent Jews

| ||||||

The Jewish Order Police Holocaust Ghettos

Jewish Order Service police units were established by the German authorities in certain locations under their brutal occupation. Almost immediately after their establishment the Jewish Councils in Eastern Europe were ordered to organise these units, usually as a forerunner to the creation of ghettos.

Whereas the Judenrat itself, although also created on German orders, often contained elements of pre-war voluntary association, the Jewish police came into being only after the German occupation. There was no precedent for the existence of a Jewish police force, and there was no indication that the Jews played any part in the establishment of a Jewish police force within the ghettos.

The Germans set the guidelines for the Judenrat to recruit members which included physical fitness, military experience, and secondary or higher education.

In practice these guidelines were not always closely followed. Formally the Jewish police constituted one of the departments of the Judenrat, but from the very beginning many Jewish Councils were apprehensive about the police force’s public character and the way it would function.

They suspected that the Germans would have direct supervision of the police and use it for the implementation of their policies. Aware of this danger, many Jewish Councils sought to establish their own means of controlling the police and the standards of its behaviour, and tried to attract young Jews who would be trustworthy.

In the initial period some of the recruits did indeed believe that by joining the ranks of the Jewish police gave them an opportunity to serve the community. But there were other reasons for joining. Belonging to a protected organisation, provided immunity from being seized for forced labour. Service in the Jewish police also offered greater freedom of movement and the possibilities of obtaining food and money.

The size of the Jewish police force was not fixed but depended on the size of the Jewish community. Thus in Warsaw the Jewish police at first numbered 2,000, in Lvov 500, in Lodz 800, in Krakow 150 and in Kovno 200.

In the larger ghettos the Jewish police commanders held officer ranks and units were made up of sub-divisions and district stations. The policemen were identified by the different caps they wore and by the unit’s designation inscribed on their armband, the yellow badge that they, like all other Jews, had to wear.

In the smaller ghettos where the Jewish police consisted of a few men organisational differentiations were not required.

The duties of the Jewish police can be divided into these categories:

The first two categories included collecting ransom payments, personal belongings and valuables, as well as taxes, fetching people for forced labour, guarding the ghetto walls and gates, escorting labour gangs who worked outside the ghetto, and as time passed conducting random round-ups of Jews to be sent to labour camps and eventually participation in the mass deportations to the death camps.

The exclusion of the Jewish population from public services and their isolation in ghettos created serious problems. In the early stage of its existence the Jewish police attended to sanitary conditions and assisted in the distribution of food rations and aid to the needy.

It also helped in the control of epidemics, and the settling of disputes – all this of course, in addition to complying with German demands. The ghetto population generally appreciated the Jewish police for these public – welfare activities. However, already at this stage, there were instances of corruption and misconduct among the police.

As time went on, the role of the Jewish police in alleviating living conditions in the ghetto was considerably reduced. The mass deportations to the death camps, commencing in early 1942, from Lodz to Chelmno and from Warsaw to Treblinka from July affected the families of the men serving in the police, their friends, acquaintances and fellow Jews, and they had to decide whether or not to stay at their posts.

Many decided to abandon the force, some in an overt manner, so as to express their solidarity with their families and with the Jewish population as a whole.

Most of the Jewish population who took this course of action were subsequently included in the transports that left for the death camps. But there were also Jewish police who remained at their posts right up to the final phases of the ghettos’ existence, carrying out the orders of the Germans till the end.

The attitude of the Jewish police towards the Jewish resistance groups took on different forms:

Warsaw Ghetto – The Jewish Order Service

The role of the Jewish Order Service in the Warsaw Ghetto will now be examined in some detail:

The Jewish police were supervised by the Polish police called the “Blue Police” because of the colour of their uniforms, refused to relinquish their control, because of its potential for income.

The Warsaw ghetto was divided into six Jewish Police districts that were formally subject to the Polish police. The commander of the Warsaw ghetto’s Jewish police was Jozef Szerynski.

Szerynski whose real name was Szenkman before his conversion to Catholicism, had been a colonel in the Polish police until the outbreak of the Second World War and had severed all his ties with Judaism, but the Nazis racial laws defined him as a Jew and forced him into the ghetto.

Adam Czerniakow appointed Szerynski and noted in his diary on the 27 October 1940, “Yesterday I engaged Lt. Col. Szerynski as head of the Order Service. “

Szerynski surrounded himself with a cadre of loyal aides. In his memoirs Stanislaw Adler described the Order Police chiefs of the Warsaw ghetto’s districts:

“Former judge, Peczenik, became chief of Region 1 which comprised the southern part of the smaller ghetto. He distinguished himself by perfectly organising the levies on baked goods and other food products for the benefit of all the functionaries of his Region, as well as for Szerynski closest entourage and himself.

When these practices gained notoriety he was transferred to Region V where the poor inhabitants there could provide only meagre pickings for the Order Service functionaries who kept trying to transfer to other regions.

Henryk Nadel, who was well liked by his subordinates, was the chief of Region II which comprised the northern part of the smaller ghetto and the southern part of the large ghetto. Later on he was transferred to Region III which embraced the area of Karmelicka, Orla and Leszno (up to the courthouse).

A former captain in the Austrian army who indulged heavily in alcohol, Lawyer Landau, was a favourite of Lederman, but he had no luck with Szerynski. In the beginning he was given Region IV which took in the Nalewki district with its numerous points of entry, but he was subsequently pushed from one Region to another, ending up, in the period before the “Resettlement” as Commander of the Reserve, considered to be the least lucrative of all appointments.

My colleague Oskar Sekler’s career in the Order Service was notable not lasting. A few weeks after Region V was entrusted to him an unusual disorder broke out. For days Sekler could not be located. After a few more dramatic events he left the Service with no regrets.

During his absence his deputy Szmerling was left in charge of the district. He was a tall, broad shouldered fellow with the strength of an athlete who liked to demonstrate his prowess at every opportunity.

Josef Hertz of Region VI had a mental illness that I am unable to classify. A medium- tall, dark haired man with a short clipped moustache, he received before the war the well deserved nickname “Satan.” Hertz was quite properly assigned to Region VI which included the Jewish cemetery.

Hertz enjoyed a well-deserved reputation as a man with clean hands. He was in a difficult economic situation, and in order to manage he took over the artistic management of a coffee house at Number 16 Sienna Street where musical and vocal performances were given.

After Peczenik had been transferred from Region I, Hertz succeeded him in that position which enabled him to improve his earning capacity at the coffee house. Region III and later Region II were taken over by Albin Fleischman. Seweryn Zylbersztajn a former superintendent in the Polish Police negotiated with Szerynski to appoint him to a police Region. Szerynski finally agreed to appoint him Chief of Region VI.”

Stanislaw Adler recalled the admission of Jakob Lejkin, who briefly took over command of the Jewish Order Service, when Szerynski was arrested in 1942. Jakob Lejkin presented some difficulties - a young lawyer who was ambitious, capable, well-mannered and indefatigably energetic. What contributed to his rejection was his height.

“I can recall vividly the caricature –like figure of little Lejkin in his rejtuzy (jodhpurs) and his canary-yellow cardigan, the future “Napoleon of the Order Service” telling everybody that he had won them for taking third place in the school for military officers.

Then, with tears in his eyes, he had to beg to have the rejection of his application to the Order Service reversed.” His request was granted and he began a rapid rise in the Order Service hierarchy. His rise and fall we will cover later.

Stanislaw Adler recalled:

“One of Szerynski’s duties was to personally submit a report every Saturday to the Security Police at their Headquarters in Szucha Avenue. He usually went with Stanislaw Czaplinski, although sometimes he accompanied Chairman Czerniakow.

I don’t know the content of those reports which were submitted to Gerhard Mende or Karl – Georg Brandt, lower ranking members of the Jewish Section of the SD. However, I do know that the Security Police received part of the weekly orders of the Jewish Order Service translated into the German language. “

The Jewish Order Police headquarters were located at Ogrodowa Street, which backed on to Chlodna Street. Adam Czerniakow noted in his diary on the 11 December 1941:

“In the morning at the Community. I inspected with Szerynski the new headquarters of the Order Service at Chlodna Street.” The Jewish Order Police and the Polish “Blue” Police played a key role in the smuggling carried out through the walls. The Jewish policemen found it to be a profitable business, whilst the Polish police, were also able to make a profit out of the smuggling.

Jozef Szerynski the commandant of the Order Service was arrested by the Germans on the 1 May 1942 on charges of smuggling furs from the ghetto to the “Aryan” side of the city.

Adam Czerniakow noted in his diary on the 1 May 1942:

“Szerynski was summonsed by the Kripo to Danilowiczowska Street for 8am. We were told, he will not return. During his absence, Jakob Lejkin his deputy was appointed head of the Jewish Order Service in Warsaw.

Adam Czerniakow recalled in his diary on 4 May 1942:

“In the morning with Lejkin to Brandt. I suggested Lejkin for the post of Sachbearbeiter. Brandt told him that he was too short. In the end Brandt accepted him.” The following day Lejkin was appointed acting commander of the Order Service and Szerynski was incarcerated in the Pawiak prison.

During the first days of the mass deportation of the Jews from Warsaw to the Treblinka death camp, which commenced on the 22 July 1942, Szerynski he was released from prison and reinstated in his position to command the Jewish police during the “Aktion.” It was Lejkin the deputy, who participated fully in the deportation “aktion,” stood out for his diligence and initiative in commanding the strategy of the deportation.

According to the testimony and writings of Jewish policemen, many of them believed that the participation of Jews in the “Aktion” would make it possible to limit its scope, prevent harm from befalling people who “deserved to be protected,” and above all avoid the prospect of the Germans taking direct action, which might result in greater harm.

Thus approximately 2,000 Order Service policemen were mobilised for the “Aktion” soon faced a complex dilemma. The Germans promised total immunity to them and their relatives and encouraged the alleged differences between them and the Jewish population of the ghetto.

During this initial period a sizeable majority of the ghetto’s population made no attempt to conceal their hatred it felt for the Jewish Order Service who played a role in the deportation activities.

As the deportation “aktion” continued the members of the Jewish Order Service began to understand what the Germans were doing, and that their own future was clouded in doubt, they began to desert the ranks of the Order Service in droves, and many sought to work in the workshops as internal guards, whilst others simply failed to appear at the morning roll calls, when daily orders were issued for man-hunts in the Warsaw ghetto.

The German’s response to this was that when the daily quotas fell short, each policeman was personally ordered to bring in “five heads” a day and those who failed to meet this target, were threatened with having their relatives taken off to make up the difference.

The Jews were herded to an assembly point called the Umschlagplatz, a square on the outskirts of the ghetto on Stawki Street by the railway sidings. The Transferstelle used this area for the handling of merchandise. An adjacent building, the former Czyste hospital, was used to hold the Jews awaiting deportation.

The Umschlagplatz was guarded by contingents of SS troops, Trawniki- manner, and the Jewish Order Service under the command of an officer called Miesczylaw Szermling, who won the German’s confidence for his stern and cruel treatment of the deportees.

This brutal deportation “Aktion” which ran from the 22 July to the 21 September 1942 saw 253,741 Jews deported from the Warsaw ghetto to the Treblinka death and a further 11,580 were sent to a Transit Camp (Durchgangslager) where they were selected to work in forced-labour camps.

The final act of the mass deportation from Warsaw took place on the Day of Atonement, 21 September 1942 and its victims were the Jewish policemen and their families. The number of Order Service police was reduced to 380.

On the 21 August 1942 Abraham Lewin wrote in his diary:

I have heard there was an assassination attempt on the chief of police Szerynski. He was wounded in the cheek. According to rumours he was wounded by a Pole from the Polish Socialist Party disguised as a Jewish policeman. Today leaflets were distributed against the Jewish police, who have helped send 200,000 Jews to their death. The whole police force has been sentenced to death.

However, it was not the Polish underground that carried out this attempt but Yisrael Kanal, a commander in the Jewish Fighting Organisation (ZOB) and a member of the religious –zionist youth movement Akiva.

A Jewish police officer in his memoirs described the attack:

During the second half of August, the attempt on Szerynski’s life was carried out. A man dressed in a policeman’s cap rang the bell of his private apartment. He told the woman who opened the door that he had a letter for Szerynski. When Szerynski walked out toward him, his head slightly turned to the side, the man shot at him and wounded him in the face.

In a rare fluke, the bullet penetrated his left cheek, a bit high, and exited through his right cheek without touching the tongue, teeth, or palate. Following this attack, the ZOB decided to assassinate Jakob Lejkin, it was thoroughly planned with great care, and the group that accepted this mission consisted of three members of Ha-Shomer ha- Za’ir.

Margalit Landau and Mordechai Grobas trailed Lejkin for some time, studying his habits and charting his regular movements and hours of work, while Eliahu Rozanski was chosen as the man to do the killing.

As evening approached on the 29 October 1942 Lejkin was shot to death while walking from the police station to his home in Gesia Street. His aide, Czaplinski, who was walking by his side, was injured.

Josef Szeryinski badly disfigured in the attack committed suicide on the 24 January 1943 just after the Second Aktion which took place between the 18 January to the 22 which saw armed Jewish resistance openly resist Von Sammern the SS and Police Leader deportation plans.

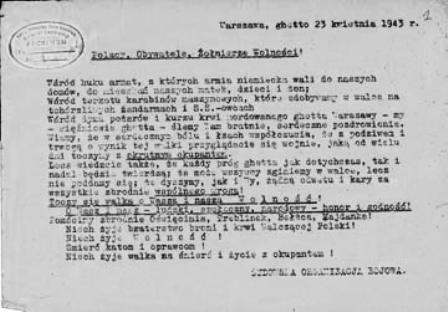

The status of the Judenrat and the Jewish police declined after the mass deportation and in anticipation of the resistance planned for January the ZOB published the following manifesto:

On January 22 1943, six months will have elapsed since the start of the deportation from Warsaw. We all remember those harrowing days in which 300,000 of our brothers and sisters were transported to and brutally murdered in the Treblinka death camp.

Six months of constant fear of death have passed without our knowing what the next day will bring. We received reports left and right about Jews being killed in the Generalgovernment, Germany and other occupied countries.

As we listened to these terrible tidings, we waited for our own turn to come – any day, any moment. Today we must realise that the Hitlerian murders have let us live only to exploit out manpower, until the last drop of blood and sweat, until our last breath.

We are slaves and when slaves no longer bring in profits they are killed. Each of us must realise this, and always keep it in mind. Jewish masses, the hour is drawing near. You must be prepared to resist, not give yourself up to slaughter like sheep. Not a single Jew should go to the railroad cars. Those who are unable to put up active resistance should resist passively, meaning go into hiding.

We have just received information from Lvov that the Jewish Police there forcefully executed the deportation of 3,000 Jews. This will not be allowed to happen again in Warsaw. The assassination of Lejkin demonstrates that.

Our slogan must be:

All are ready to die as human beings.

Sources: The Jews of Warsaw 1939 -1943 by Yisrael Gutman, published by The Harvester Press Brighton 1982 In the Warsaw Ghetto by Stanislaw Adler, published by Yad Vashem 1982 Abraham Lewin – A Cup of Tears, published by Fontana Collins 1988 The Warsaw Diary of Adam Czerniakow, published by Elephant Paperbacks, Chicago 1999. The Encyclopaedia of the Holocaust Holocaust Historical Society Ghetto Fighters House The Wiener Library .

Copyright: Chris Webb H.E.A.R.T 2008

|