Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Ghettos

Lublin Introduction to the Ghettos of the Holocaust

Jewish Ghettos The Judenrat Judenrat Leaders Prominent Jews

| ||||||||

Lublin Occupation & The Ghetto

Lublin’s population in 1939 stood at 122,000 people, including 42,830 Jews, approximately one-third of the inhabitants. Lublin was an important centre of Jewish religion, culture, education and social life.

In 1930 the Yeshiva Chachmel – Yeshiva of the Wise Men in Lublin – was established, this became a world-famous rabbinical high school.

In the Jewish community there were twelve synagogues before the war, and approximately one hundred private prayer houses, three cemeteries, a Jewish hospital at Lubartowska Street, children’s orphanage, old people’s home, schools and two newspapers, “Lubliner Tugblat” and “Lubliner Stimme”, the “Lublin Daily” and “Lublin Voice” respectively, both published in Yiddish.

In the city many Jewish organisations were very active, and the Jews had their own representation in the town council and with many commercial and social organisations Jews dominated in trading.

Jews owned more than 50% of the workshops and approximately 30% of the factories, particularly prevalent in tailoring, leather goods and as gold and silversmiths. There was however, a low level of assimilation, out of 42,000 Jews approximately 1,000 declared to use the Polish language, although most of the younger generation spoke Polish fluently.

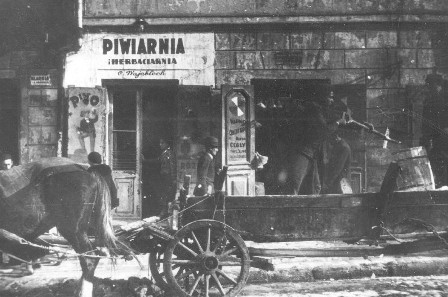

On 18 September 1939 German troops entered the city after a short battle in the suburbs, and a deadly bombardment on the 8 September 1939, where many buildings were destroyed.

On 14 October 1939 the Lublin Jewish community received an order to pay 300,000 zloty as a contribution to the German army. German soldiers rounded up Jews in the streets and forced them to work clearing up the bomb damage, and other tasks.

Many Jews were beaten, tortured and humiliated, whilst German soldiers robbed Jewish shops and apartments. The German’s destroyed the books in the Talmudic Acadamy in Lublin, which was described as such

“We threw the huge Talmudic library out of the building and carried the books to the market place where we set fire to them. The fire lasted twenty hours. The Lublin Jews assembled around and wept bitterly, almost silencing us with their cries. We summoned the military band, and with joyful shouts the soldiers drowned out the sounds of the Jewish cries.”

On 25 October 1939 a registration was carried out, 37,054 Jews lived in Lublin, but many younger Jews and political activists left the city, and tried to reach the part of Poland occupied by the Russians.

The German civil administration under Governor Ernst Zorner which was located at the Distriksstrasse, was established on 1 November 1939, as part of the creation of the Generalgouvernement.

Lublin’s central city park, Park Litewski, on the city’s main commercial thoroughfare Krakowskie Przedmiecie, was re-named Adolf Hitler Park. One building the former Stefan Batory College, was renamed the Julius Schreck Kaserne, at 17 Pieradzkiego Street, and later became the headquarters of Aktion Reinhard programme.

Streets were given German names such as Reinhard Heydrich Strasse and an Ostlandstasse. Entire buildings, residential and administrative, were commandeered by the SS and German Civil administrators. Poles and Jews were forcibly moved from their property, to other parts of Lublin or to places in the Lublin district.

German replaced Polish and Yiddish in the streets, in the shops, workshops and offices. German flags and banners and the black Swastika, were visible, draped from the facades of most large structures, generally hanging over main entrances.

On 9 November 1939 Odilo Globocnik, former Gauleiter of Vienna was appointed SSPF Lublin – SS and Police Leader for the Lublin district and he reached the city with his staff during the second week of November.

On the same day the first resettlement of Jews took place in the city – in the early hours of the morning SS-men surrounded the centre of the city and removed the Jews from their dwellings. Most of them lost their property within a few minutes, and were resettled to the Jewish Town and Old Town in Lublin.

As before, many took the opportunity to leave the city. Following the decree dated 23 November 1939 by Dr Hans Frank the Generalgouvernor the Jewish population from 10 years old had to wear an armband with the Star of David, and that all Jewish shops, factories and workshops also had to display a “Star of David”

In November 1939 Herr Veit Harlan paid a visit to Lublin in order to photograph scenes for the Nazi film, Jew Suss. Towards the end of 1939 the Lublin Jewish Council – Judenrat was established, as per Reinhard Heydrich’s edict, 24 members had to be appointed by the Jews themselves.

The first elected president of the Lublin Judenrat was Ing. Henryk Bekker. – before the war he was the leader of the Folkspartaj in Lublin, deputy to the Town Council and president of the Jewish Community Council.

Vice presidents of the Judenrat were Dr Marek Alten, who was a lawyer, former Austro- Hungarian officer, and one of the leaders of the Zionist Organisation in Lublin, and Salomon Kestenberg, who was a well-known paper merchant and vice-president of the pre-war Jewish Community Board.

Henryk Bekker was regarded by survivors who knew him to be a kind and helpful person. Other Jewish institutions were formed like the Jewish Self-Help (Judische Soziale Selbshilfe), the Judenrat controlled all aspects of Jewish life, and were the sole representative of the Jewish community with the German authorities.

The Lublin district it had been decided was to be turned into a Jewish reservation – Judenreservat, where Jews from the Reich and its incorporated territories would be resettled there.

From December 1939 until February 1940, tens of thousands of Jews were deported to “Lublinland.” These mass deportations, which were organised by the SS, without any co-ordination with the civilian authorities of the General Gourvnement and without preparations in the area, were stopped after objections from Hans Frank, who complained to Hermann Goring in Berlin.

Most of the Jews deported to the Jewish reservation were sent to the small ghettos in Piaski, Glusk and Belzyce, as well as Lublin itself. In December 1939 the Commander-in – Chief East, Field –Marshall Blaskowitz, reported that “children were arriving in the deportation trains from the incorporated territories frozen to death and that people were dying of hunger in the reception villages.”

In 1940 the SS and police organised round-ups in Lublin and its environs – thousands of Jews were sent to the labour camps in and around Belzec, where they built the so-called “Eastern Wall” the border fortifications between the General Gouvernement and the Soviet territory.

Many died in the awful conditions of the labour camps, primitive living conditions, poor food, disease and ill-treatment all played their part. In March 1941 Lublin’s governor Zorner proclaimed the establishment of a ghetto in Lublin, it was located in the oldest and poorest part of the historical Jewish district in Lublin’s old town.

Several days before the establishment of the ghetto approximately 14,000 Lublin Jews, most of them unemployed and poor, were resettled to several small towns in the Lublin district, but some of them returned to Lublin.

Around 40,000 lived in the ghetto. Until March 1942 the ghetto was not strictly sealed, but Jews were not allowed access to the streets reserved for “Ayrans” . Many Jewish families, particularly those who were “specialists” for various German institutions and concerns still lived outside the ghetto.

The conditions in the Lublin ghetto, regarding the supply of food, was not as horrible as in the ghettos of Warsaw or Lodz. The Jews of Lublin had contact with the outside world enabling them to smuggle food into the ghetto area.

Even local Nazi newspapers wrote about the large scale illegal trading. Dr Max Freiherr Du Prel wrote in his book Das General Gouvernement in March 1942 regarding the Lublin ghetto – “in filthy dens, dug-outs and catacombs the Jew feels at home.”

Up until March 1942 many Jews from Warsaw escaped to Lublin, believing that living conditions were better, with a better supply of food – indeed this was true, the biggest problems in the Lublin ghetto were typhus epidemics and overcrowding.

From October 1941 the Nazi administration prepared the eventual expulsion of the Jews of Lublin, apart from the 25,000 working for the German army, the SS and police. In December 1941 groups of young Jewish men were brought to Majdanek for constructing the camp.

Early in 1942, the ghetto was divided into two parts A and B. Ghetto A was known as the Big Ghetto with unemployed Jews, Ghetto B was several streets, Grodzka Street, Kowalska Street, Rybna Street. The Judenrat and its institutions were located in Ghetto B.

Jews who worked for the Germans and doctors who worked in the Jewish hospitals also lived in Ghetto B, which was fenced in with barbed wire. Jews living in Ghetto A and Ghetto B were allowed to visit each other at special times during the day only, which required special permission.

The Germans already knew at the time of the creation of the two ghettos, that the Jews were shortly going to be deported and exterminated in the Belzec death camp, which was in the process of being built by Globocnik’s SS officers, who were based at the Julius Schreck Kaserne, in Litauer Strasse.

Several days before the deportations commenced the SS registered all Jewish workers – they received a Sicherheitspolizei stamp mark, in their Identity Cards – only these people were exempt from deportation and they were moved to Ghetto B.

On 16 March 1942 several hours before the beginning of the liquidation of the ghetto, SS – Hauptsturmfuhrer Hermann Hofle met the representatives of various Nazi institutions in Lublin. They were informed that all unemployed Jews would be deported to Belzec – “ which is the last station in the Lublin district, and these people will not return to the General Gouvernement.

For the Jewish workers SS were building a large camp Majdanek which will be the main reservoir of the Jewish labour force for German factories in Lublin. He promised that during the deportation the SS would select people for work.

At 10pm the ghetto was surrounded by SS and Ukrainian- SS from the training camp at Trawniki. The main ghetto street was lit which shocked the people being driven from their homes.

Many of the Jews, especially the elderly and sick were shot on the spot. Two hours later SS- Obersturmfuhrer Hermann Worthoff from the Lublin Gestapo who was responsible for Jewish affairs met the Judenrat and he ordered that every day around 1,500 people had to be deported “to the East for work”.

Everyone would be allowed to take 15kg of luggage on the journey along with valuables and money. Meanwhile the first group of Jews were brought to the Great Synagogue, now being used as a collection centre for the Jewish deportees. On the same night they were taken to the Lublin Umschlagplatz near the town’s slaughterhouse

Early in the morning of 17 March 1942 the first of Lublin’s Jews were deported to the Belzec death camp. At this time none of the Jews knew about the destination nor the fate of the deportees.

But several days after the beginning of the deportation action a young unknown boy escaped from the Belzec death camp – returning to Lublin he explained the fate of the deportees but no –one wanted to believe him. Until 14 April 1942 approximately 26,000 Jews from Lublin were deported to Belzec – about 200 children from the Jewish Orphanage were executed together with their teachers in a Lublin suburb.

Several hundred patients from the Jewish hospitals were shot in the Niemce Forest some 15 kilometers from Lublin, together with their doctors and nurses. During the murderous ghetto liquidation the SS changed the regulations regarding the “Work Jews.” All those working for the Germans had to change their kennkartes into a Juden- Ausweis.These people were exempt from the next wave of deportations – according to the SS orders only 2,500 Jews were allowed to stay in the ghetto officially.

On 30 March 1942 Worthoff ordered the selection of the Judenrat members and other officials. The president of Lublin’s Judenrat Ing. Henryk Bekker and other members such as Dr Josef Siegfried, who was president of the Jewish Self-Help organisation, were deported to the Belzec death camp the same day.

Ing. Henryk Bekker probably knew the fate of his fellow deportees – he went to the deportation train wearing ritual Jewish clothing and without any luggage.

Also deported with the Judenrat members were 35 Jewish policemen and their families, to their deaths in Belzec. The deportations were halted on 14 April 1942 – the SS knew that around 7,000 – 8,000 Jews were still hiding in cellars in the Old Ghetto dwellings. The deportations from the Lublin ghetto to a death camp was the first in the General Gouvernement and the Nazis gained much experience for the future deportation actions.

In 1942 the robbing of the Jewish victims was also referred to as “Catholic Action” in some quarters in Lublin because the main depot for the plundered loot was stored in a building that had been erected before the war by the Catholic Action organisation, at 27 Chopin Strasse.

Therefore Worthoff and other members of the Gestapo staff responsible for deportations such as Dr. Harry Sturm, Walther Knitzky and Kalich ordered the transfer of all the remaining Jews to the small ghetto of Majdan Tatarski.

Majdan Tatarski ghetto was located in the neighbourhood of the forced labour camp at the Old Airfield / Alter Flugplatz. The Jews in this ghetto could even watch their comrades working in the Alter Flugplatz camp. In this camp the possessions of the Jews murdered in Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka death camps was sorted.

Before the war approximately 1,500 Polish people lived in Majdan Tatarski mainly workers at the aircraft factory Plage-Laskiewicz. In this new ghetto there was an acute lack of accommodation and many Jews lived on the streets or in the courtyards.

On 22 April 1942 approximately 2,000 – 2,500 Jews, mostly women with children having no Juden- Ausweis were taken to the Krepiec Forest and shot.

200- 300 young men were selected and sent to Majdanek concentration camp – rumours about the fate of all these people spread amongst the ghetto inhabitants.

After these selections about 4,000 Jews lived in the Majdan Tatarski ghetto, which was now closed with a barbed wire fence. The president of the new Lublin Judenrat was Dr. Marek Alten, but the man with the biggest influence in the ghetto was Shama Grajer.

Before the war Shama Grajer was a barber and the owner of a brothel in the Old Town. During the occupation he was on very friendly terms with the Gestapo. At his Lubartowska Street restaurant the SS deportation staff gathered.

He provided them with the best food and drink and Jewish musicians played for their entertainment. Grajer even sold Juden- Ausweis for many people, taking thousands of zlotys and was involved in corruption. In Majdan Tatarski he was called the “Jewish King.” He participated in selections and decided who would be selected for imprisonment in Majdanek.

In September 1942 about 1,000 Jews were deported to the ghetto in Piaski near Lublin, the next selection took place on 24 October 1942. Among the deportees in the latter deportation were so-called privileged Jews, such as officials of the ghetto’s labour office (Arbeitsamt) and workers from Victor Kremin’s company, who up until then had been exempt. These people were taken to Majdanek concentration camp.

On 9 November 1942 the last group of Majdan Tatarski’s ghetto inhabitants numbering about 3,000 people, were deported to Majdanek concentration camp, in order to comply with Himmler’s orders given that June, to liquidate the ghettos, and transferring the inhabitants to death camps and concentration camps.

About 180 people were shot in the ghetto, most of them children, or people trying to find a hiding place. Hermann Worthoff personally shot Dr Marek Alten, Shama Grajer and Moniek Goldfarb who was commander of the Jewish ghetto police.

They were killed on the personal order of Odilo Globocnik in order to eliminate all witnesses of corruption by the SS. In Majdanek selections continued daily old people, sick people and children were sent to the gas chambers, whilst others were selected for work.

From Majdanek prisoners were transferred to other labour camps in Lublin such as Lipowa Street, the Old Airfield or the Sportplatz or other smaller enterprises. Specialists were transferred to the Gestapo prison in the castle, where they worked as personal slaves for the higher ranking Gestapo officers and their families.

The Jews who worked in the labour camps in Lublin were executed during the mass execution known as Aktion Erntefest, conducted by Jakob Sporrenberg, the SSPF successor to Odilo Globocnik, on 3 November 1943.

On this day approximately 18,000 Jews from camps in Lublin were executed by shooting in specially dug pits in Majdanek concentration camp.

The last group of some 400 -500 Lublin Jews, working at the castle survived until July 1944. Together with many Polish political prisoners they were shot on 21 and 22 July 1944, a few hours before the Soviet forces liberated the city. Hermann Worthoff was responsible for these executions, had previously liquidated the Lublin ghetto, and also took part in the Warsaw ghetto liquidation.

The Jews killed on the eve of liberation had been selected by Worthoff to work as Hofjuden for the Gestapo in the castle, during the Aktion Erntefest, but now he ordered them to be killed.

Only two or three Jews survived from this final massacre, the Polish political prisoners murdered that day had been under investigation by Worthoff, and had been sentenced to death during the final days of the occupation.

Out of approximately 42,000 Jews of Lublin only 200-300 survived the holocaust either by hiding or surviving various camps.

Sources:

The Final Solution by G. Reitlinger – Vallentine Mitchell &Co Ltd 1953 . Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka by Yitzhak Arad published by Indiana University Press – Bloomington and Indianapolis 1987 The Holocaust – The Jewish Tragedy by Sir Martin Gilbert published by Collins London 1986 Documents from the Lublin Ghetto – Judenrat Without Direction by N. Blumental – Jerusalem 1967 Odilo Globocnik – Hitler’s Man in the East by Joseph Poprzeczny published by McFarland &Company Inc Publishers 2004 Das General Gouvernement by Dr. Max Freiherr Du Prel published by Konrad Triltsch Verlag Wurzburg 1942 Listy z piekla by S. Erichman- Bank – Bialystok 1992 The Undefeated by S. Goldberg- Tel Aviv 1985 Kronika wydarzen w Lublinie w okresie okupacji hitlerowskiej by J. Kasperek – Lublin 1983 Lublin – Jerozolima Krolestwa Polskiego by R. Kuwalek and W. Wysok – Lublin 2001 Lubelska dzielnica zamknieta by T. Radzik – Lublin 1999 Collection of Lublin’s Judenrat 1939 -42 and Collection of Governor of Lublin District 1939 -1944 – State Archive in Lublin Collection of Survivors Memoirs and Testimonies – Archive of the Majdanek State Museum Records from the trials against Hermann Worthoff and Dr Harry Sturm - Institute of the National Remembrance in Warsaw Documents and photographs from the Holocaust Historical Society Mike Tregenza – private archive

Copyright: SP and CL H.E.A.R.T 2007

|