Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Ghettos

Introduction to the Ghettos of the Holocaust

Jewish Ghettos The Judenrat Judenrat Leaders Prominent Jews

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Judenrat "Council of Elders"

The name Judenrat refers to the Jewish Councils established on German orders in the Jewish Communities of Nazi occupied Europe. Jewish councils were first instituted in occupied Poland following instructions given by Reinhard Heydrich on 21 September 1939, and through an order promulgated by Hans Frank, the Gouvenor of the General Government, on 18 November 1939 and subsequently in other countries occupied by the Nazis.

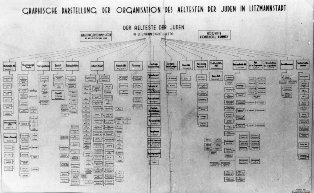

The Jewish Councils did not have a uniform structure, some of them held authority in one location only, whilst others administered Jewish communities throughout a district or even an entire country. The role played by the Judenrat in Jewish public life during the holocaust is one of the most controversial issues.

Some historians believe that the Judenrat had a debilitating effect on the strength of the Jewish communities, whereas other historians argue that the Judenrat reinforced the Jews power of endurance in their struggle against the Nazi onslaught.

On the basis of Heydrich’s instructions Jewish Councils were set up over the course of a few weeks in September and October 1939 in the communities of central and western Poland. The guidelines stipulated that the Jewish Council would be fully responsible for the implementation of German policy regarding the Jews and would be made up of influential people and rabbis.

In this way, the Jewish communities had forced on them a body whose function was to receive German orders and decrees and be responsible for carrying them out. The inclusion of prominent personalities in the Jewish council had a dual purpose to ensure that German orders were implemented in full and to discredit Jewish leadership in the eyes of the Jewish population.

Under Hans Frank’s order, in places where the Jewish population did not exceed ten thousand the Judenrat was to have twelve members, and in larger towns or cities it was to consist of twenty – four members. Adam Czerniakow the Chairman of the Warsaw Judenrat wrote in his diary on the 4 October 1939:

“Unfortunately, before I could enter the building I was stopped by the police and for the time being I can do nothing. I was driven to Szucha Avenue – the location of the Security Police and was ordered to co-opt 24 men for the Community Council and to assume its leadership. I prepared a statistical questionnaire.”

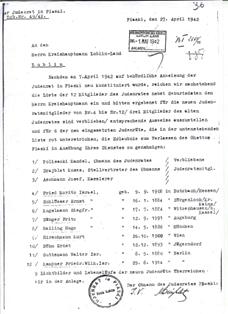

The councils were to be elected by the members of their community and were themselves to elect their chairman and vice-chairman. The process of electing the Judenrat and their top two officers was to be completed by 31 December 1939.

The results were subject to the approval of the German Kreishauptmann or in the cities, of the German Stadthauptmann. This last provision meant in effect that the elections provided for in Frank’s order were quite meaningless, and that the Germans never intended to have the composition of the Jewish councils determined by elections.

German intervention in the process, however, was not absolute and on a number of occasions active members of the Jewish community had a say in determining the composition of the council. In some cases, Jewish activists refused to join the Judenrat because they were suspicious of the true German’s intentions regarding the Jewish councils.

Generally, however, local Jewish leaders did become members of the council’s, this corresponded to the wishes of the Jewish population, who felt the traditional, experienced leaders of the community who were best equipped to represent them in the day to day dealings with the German authorities.

Thus in the initial stages of their existence, the Jewish Councils preserved the continuity of local leadership, but in some instances some members of the Jewish councils had no previous experience of public affairs.

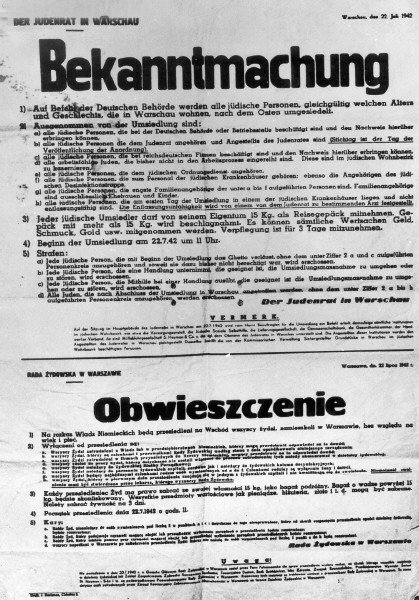

Once the Judenrat were established, the Germans lost no time in presenting them with urgent tasks, such as drafting people for forced labour, undertaking a census of the Jewish population, evacuating apartments and handing them over to Germans, paying fines and ransoms, confiscating valuables owned by Jews, and paying for the construction of ghetto walls, etc.

In most cases, the members of the Judenrat tried to delay the administrative and economic measures that the Germans were imposing, or at least to alleviate them. However, the traditional methods employed by Jews for dealing with the authorities, such as lobbying officials and utilising personal contacts, were not applicable under the new conditions.

The Jewish council’s members did try to exploit the rivalry among the various branches of the German administration in order to lighten the burden imposed on the Jews, but their success here was minimal.

The Jewish Councils believed that by complying with the German demands they would impress upon the Nazis the vital importance of the Jewish community to the Germans. In this way they hoped to avert or moderate some of the blows, to gain time, to ward off or delay collective punishments and perhaps even to persuade the Germans to reconsider their policy in view of the benefit they could derive from the Jews, as a reservoir for the manpower the Germans sorely needed.

In the meantime, the Jews hoped the Germans would be defeated and they could be somehow saved, this notion was of course severely put to the test, when the Germans started the mass round up of Jews to the death camps. The Jewish council were also involved in providing the basic needs. The German invasion of Poland, and subsequently of other countries, destroyed the existing Jewish economic structure, which had been frail even before the Second World War.

The Jewish society had always included groups requiring public assistance, but the problems created by the German occupation were of unprecedented dimensions. Various measures imposed by the Germans upon the Jewish community caused a further deterioration of their economic situation.

Tens of thousands of Jews were displaced from their homes and became refugees, without a place to live or a source of food. Jews were no longer covered by the general public services and required their own health services and public institutions, such as homes for the elderly, orphanages, and educational institutions.

In coping with this daily for the survival of the community, the Jewish Councils members drew upon their experience gained in Jewish welfare activities before the war, even though there was no comparison between conditions pre-war and during the Second World War.

The Jewish Council’s efforts to ease the plight of the Jewish population were among the ways it sought to counter the brutal Nazi policy of starving the communities and breaking their power of resistance. Even in that first stage however, some of the Judenrat activities were not without instances of protectionism, favouritism, misuse of positions of public trust for personal advantage, and so on. Such practices caused bitter resentment in the communities and were harshly criticised.

More functions were imposed upon the Jewish Councils by the Germans with the establishment of ghettos for the Jews first in occupied Poland, and then later in the Soviet Union. The Jewish council’s were responsible for transferring the Jews from their homes into the areas allotted for the ghettos, for providing accommodation in the ghettos for the new inhabitants, for maintaining public order in the ghettos for preventing smuggling. Some of these duties were carried out by the Jewish police.

Under ghetto conditions, which separated the Jews from the general population, the living conditions became much worse, large sections of the Jewish community faced an agonising slow death by starvation. It was the Jewish council’s responsibility to distribute the food rations permitted by the Germans, these food rations were the absolute minimum for survival, and large numbers of the ghetto’s population perished through starvation.

In a number of ghettos the Jewish Councils sought to obtain more food by buying provisions on the black market or on the “Aryan” side, or by bartering products manufactured in the ghetto. The Jewish councils also established organisations for mutual help, thereby providing some relief for the masses from their suffering.

As a result of starvation, over-crowding and the lack of basic sanitary facilities, diseases spread quickly in the ghetto. The Germans held the Judenrat responsible for ensuring that contagious diseases did not cross the ghetto borders, but they regarded the growth of the death rate in the ghettos as an aid to their “final solution” of the Jewish problem.

The Jewish Councils, for its part, set up hospitals and clinics and organised other forms of medical aid in order to reduce, as much as possible, the dimensions of the diseases and epidemics. In many ghettos, other community organisations waged war on starvation and disease through such unofficial frameworks as political organisations and youth movements.

In Poland, the Zydowska Samopomoc Spoleczna (Jewish Self-Help Society), an organisation recognised by the German authorities, sought to provide help to the needy. In some cases the Judenrat and the voluntary organisations cooperated with one another, but friction arose when the Judenrat wanted to exercise supervision over all welfare and medical- aid operations among the Jewish population.

Beginning in 1940, the Jewish council’s were given the task of providing forced labour for the camps that were being set up, first in occupied Poland and later in other occupied areas. This was a fundamental change from the Jewish Councils previous responsibilities. It did not mean sending people on forced labour in or near their place of residence where they could return in the evening to their community and family - it meant total separation and transfer to remote locations where a much harsher regime was in force – a regime that caused a great number of deaths.

The Jewish Councils had to make a decision whether to comply with the German demands regarding forced labour - in most instances they supplied the required quota of able-bodied young men as workers for the labour camps, causing friction within the community when the latter were seized on the streets because the Germans needed more workers.

In the initial stages of deportations for forced-labour the Judenrat tried to make contact with the members of their community imprisoned in the camps, sending them food, clothing and medicines, but when German policy took a turn for the worse, the contact was broken off. Czerniakow made an entry in his diary dated 25 August 1940:

“Zabludowski is back. Our workers are in a camp at Belzec, a long way from Lublin. The camp is not under the control of the Arbeitsamt. Whether they are paid is not known. We are sending four doctors there with instruments and drugs.”

In some cases the Jewish Councils refused to supply quotas for the forced-labour camps, for example when Joseph Parnes, chairman of the Jewish Councils in Lvov, refused to send men to the Janowska camp, he was killed. As time went on, however, and Nazi policy moved towards mass extermination the Jewish Councils were left with very little room to manoeuvre, between the needs of the Jewish community and the demands of the German authorities.

Jewish Council members had to confront the question of where to draw the line – to try and comply with German demands no matter how unreasonable, to save individuals or groups of Jews, implementing harsh regulations, trying to satisfy the demands of the Germans, whilst retaining the confidence of the wider Jewish population.

On this issue there were bitter discussions within and outside the Jewish Councils. The decisions taken by the council members and the answers they gave often alienated the population, as these few examples from the diary of Adam Czerniakow will illustrate:

November 24 1939

A delegation of tenants from 9 Nalewki Street concerning the arrest of all the men there.

November 25 1939

In the afternoon the SS. Mothers from 9 Nalewki Street – it transpired in the evening that it may be possible to deliver 100,000 zloty to the SS. By noon 40,000 zlotys were collected. At 5.30 I took 102,000 zloty – we need another 38,000. A very difficult moment, but in the end permission was granted to make the last payment on Monday

November 28 1939

Dr Kluge informed me that the 53 residents of 9 Nalewki Street were shot. At 11 the relatives in the community building. Some of the councillors advise postponing the notification of the families until tomorrow. I reject the suggestion. I summoned the waiting families. A scene very difficult to describe - the wretched people in confusion. Then bitter recriminations against me.

December 1 1939

According to information just obtained in the Community, the families of the 53 have been looking for a scapegoat. Who could serve this purpose better than I. The cleaning lady tells me that that one woman called me a murderer; others were spreading rumours that the exaction was paid too late, still others that I knew about the death sentence and kept this information secret.

July 19 1942

Incredible panic in the city. Kohn, Heller and Ehrlich are spreading terrifying rumours; there is talk of about 40 railroad cars ready and waiting. It transpired that 20 of them have been prepared on SS orders for 720 workers leaving tomorrow for a camp. Kohn claims that the deportation is to commence tomorrow at 8pm with 3,000 Jews from the Little Ghetto. He himself and his family slipped away to Otwock.

July 20 1942

In the morning at 7.30 at the Gestapo. I asked Mende how much truth there was in the rumours. He replied he heard nothing. I turned to Brandt, he also knew nothing. When asked whether it could happen, he replied that he knew of no such scheme. Uncertain I left his office, I proceeded to his chief Kommissar Bohm, he told me that this was not his department but Hohmann might say something about the rumours. I mentioned that according to rumour the deportation is to start tonight at 7:30.

He replied that he would be bound to know if it were about to happen. Not seeing any other way out I went to the deputy chief of Section lll, Scherer. He expressed his surprise hearing the rumour and informed me that he too knew nothing about it. Finally I asked whether I could tell the population that their fears were groundless. He replied that I could and that all the talk was Quatsch und Unsinn (utter nonsense).

I ordered Lejkin to make the public announcements through the precinct police stations. I drove to Auerswald. He informed me that he reported everything to the SS Polizeifuhrer. Meanwhile First went to see Jesuiter and Schlederer, who expressed their indignation that the rumours were being spread and promised an investigation.

July 22 1942

Sturmbannfuhrer Hofle and associates came at 10 o’clock. We disconnected the telephone. We were told that all the Jews irrespective of sex and age with certain exceptions, will be deported to the East. By 4pm today a contingent of 6,000 people must be provided. And this at the minimum will be the daily quota.

So Czerniakow despite going to see various Police and Security police members was lied to about deportations and encouraged to pacify the Jewish population, when these individuals knew that mass deportations to the death camp at Treblinka were about to commence.

It is against this kind of backdrop that form the basis for valued judgements of the Judenrat, the events above highlights the impossible corner the Nazis had painted them into, the terrible tragedy that was about to unfold which was beyond the comprehension of most normal human minds.

The pattern of behaviour of the members of the Judenrat falls into four categories.

1.) Non cooperation with the Germans over economic issues. 2.) Acquiescence over the seizure of property, but not people. 3.) Resignation over the partial destruction of the community. 4.) Compliance in full with German orders, for their own personal interests.

A study on the fate of 720 Judenrat members in eastern Europe show that close to 80% of Judenrat members died before the mass deportations took place, or during the deportations itself.

Fate of 720 Judenrat Members in Eastern Europe

Study: Isaiah Trunk

Relations between the Judenrat and the Jewish underground and fighters organisations were highly complex and did not follow a uniform pattern. A substantial number of Judenrat were opposed to the idea of armed resistance or of escaping to the forests to join the partisans.

Some Jewish Council members believed that underground activities in the ghetto would endanger the entire community and hasten its liquidation, in view of the rule of “collective responsibility” that the Nazis had introduced.

This was the background to the tension in many ghettos where the Jewish Councils and the underground completed for influence, in some locations feelings ran so high violent clashes erupted, for example the Jewish Fighting Organisation (ZOB) attacked the Jewish police, and in Vilna where a dispute took place over the Yitzhak Wittenberg affair. In Eastern Upper Silesia Jewish Council chairman Moshe Merin waged all-out war against the underground, similar situations existed in Krakow and other locations.

Some Jewish council’s did not have a clear-cut policy on the issue of Jewish resistance, they accepted the presence of an underground and even gave it help, but argued that if active resistance took place prematurely, it would interfere with their policy of hoping to gain time in the hope that the tide of war would turn against the Germans, and the Jews could be rescued.

While supporting the concept of resistance the Jewish Councils felt it should only be implemented only when it was clear that the community was about to be liquidated, this was the position held by Efraim Barasz the Jewish Council chairman in Bialystok.

In other ghettos, such as those in Kovno and Minsk, Jewish Council members assisted the underground without reservations of any kind, there were also instances where Jewish Council members led underground activities and played crucial roles in uprisings. For example Dov Lopatyn, the Jewish Council chairman in Lachva was one of the leaders of the uprising there, in which the whole community took part.

In other countries occupied by the Nazis Jewish councils were established in France a central Judenrat, the Union Generale Des Israelites De France (UGIF) was set up on 29 November 1941. It consisted of two branches, one in German –occupied northern France and the other in Vichy France, in the south.

All other political and public Jewish organisations were shut down, though most continued to operate as independent bodies under the cover of UGIF departments, which enabled them to combine their legal functions with their clandestine aid and rescue operations. The UGIF was headed by prominent pre-war Jewish leaders who took no part in the arrest, imprisonment, and deportation of Jews, and who tried to ease the overall lot of the French Jews.

In Belgium the order for the establishment of a Jewish Council was announced on 25 November 1941, it was named the Association Des Juifs En Belgique (AJB) and the Chief Rabbi of Belgium, Solomon Ullman, was appointed its chairman. The AJB, with local branches in the Belgian cities, was charged with setting up a register of the Jewish population that the Germans could utilise in drafting Jews for forced labour and deportation.

Most of the time the AJB complied with the orders it received from the Germans, thus causing bitter resentment and resistance among the Jews. In the summer of 1942, Jewish Council members delivered to the Jews notices from the Germans ordering them to report for forced –labour- in reality a cover for deportation to the death camps. As a result, other Jews who had been working for the Jewish Council decided to resign, however AJB members once again passed on German decrees, but on the other hand there were also many AJB members who established links with the Jewish underground and other general Jewish organisations during that period and who made their contribution to the resistance and rescue efforts.

The Germans established a Judenrat, the Joodse Raad, in the Netherlands in early 1941, its authority at first was restricted to Amsterdam, but within a short time was extended to the whole country. David Cohen and Abraham Asscher, two veteran leaders of the community, were appointed as heads of the Judenrat. In the first phase of its existence, the Joodse Raad organised services needed by the community, but it was also charged with various tasks that served German interests, such as registering the Jewish population throughout the country.

In the summer of 1942 the Joodse Raad was ordered to draw up a list of persons who were to be sent “to work in the east.” Following an intense internal debate, the council agreed to provide the Germans with 7,000 names. For this action and for other instances of compliance with German orders, the Judenrat in the Netherlands was severely criticised at the time and also in the post-war years.

In Slovakia a central Judenrat, the Ustredna Zidov – Jewish Centre was established in September 1940, with its headquarters in the capital, Bratislava, and branches in other cities. It was the only institution authorised to represent the Jews and its officers were well known public figures. The council sought to provide the Jewish population with essential services, give aid to the needy, create employment and establish vocational training courses.

Following the 1942 deportations from Slovakia, it increased its activities in the labour camps, setting up workshops and organising construction crews with the object of demonstrating that the Jews played a vital role in the country’s economy. Some members were inclined to submit to German demands, one of these was Karel Hochberg, who wielded considerable influence in the Jewish Council.

During the deportations an underground group, the Pracovna Skupina was formed within the council, under the leadership of Gisi Fleischmann and Rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandel, who did not belong to the latter. In addition to their official duties in the Ustredna Zidov, the Pracovna Skupina members initiated aid and rescue efforts, during which they made contact with elements outside Slovakia. It was they who put forward the so-called Europa Plan, a proposal for rescuing the surviving remnants of European Jewry.

A central Judenrat for Hungary was established in Budapest during March 1944, under the name of Zsido Tanacs, its chairman was Samu Stern, a leader of the Neolog movement in Hungary and the president of the Jewish community in Pest.

Local councils were formed in other Hungarian cities, both the central and local councils in Hungary complied with the administrative and economic measures that were imposed on the Jews. Although the Judenrat members in Hungary were well aware of the Germans true intentions regarding deportations and extermination, as they had been informed of the slaughter of Jews in other countries, they gave no warning to the Jewish population

In Rumania the Centrala Evreilor – Jewish Centre went into operation in Bucharest at the beginning of 1942, with branches in various cities. The Union of Jewish Communities which until then had administered Jewish community life in the country was disbanded. Nandor Ghingold, a baptized Jew who was totally unknown among the Jewish population, was appointed chairman of the council, which was directly subordinated to Radu Lecca, the Rumanian official in charge of Jewish affairs.

The council operated in four areas, preparing surveys of the Jewish population, drafting Jews for forced labour, collecting fines imposed on the Jews and organising welfare assistance. The Germans monitored the council’s activities and exerted pressure on the Rumanian government to use it in a manner designed to weaken the public standing and influence of Dr. Willhelm Filderman, who had been the head of the Union of Jewish Communities, and of other traditional Jewish leaders.

The attempt failed, and Filderman and the other veteran leaders worked to block the efforts of the Germans and their Rumanian henchmen. The Jewish Centre on the other hand never gained the recognition of the Jewish population.

In Greece the Germans took Salonika on 9 April 1941, some two months before all of Greece was occupied on 2 June 1941 and divided between Germany, Italy and Bulgaria. The Gestapo immediately seized some of the Jewish community leaders of Salonika – whom they considered potential sources of resistance – and appointed Shabbetai Shealtiel, an employee of the Jewish Community Association, as head of a newly constituted community board.

The board was ordered to supply men for forced-labour and to implement anti-Jewish economic measures, it complied with these demands. Shealtiel proved to be incompetent and in December 1942 he was dismissed and the Chief Rabbi of Salonika Zvi Koretz was appointed in his place. From this point on the board lost all autonomy, rapidly assumed all the characteristics of a Judenrat and was forced to carry out German orders to the letter.

When deportations from Salonika to the Auschwitz and Treblinka extermination camps in Poland were launched in March 1943, Koretz tried to stop them, appealing to the Greek authorities to intervene on behalf of the Jews, but his efforts failed.

Many historians will argue the Judenrat could have done more to warn the Jewish communities, resist the Nazi oppressors more effectively, whilst others will argue that on the whole they did their best, with what they knew at the time, and were placed in a truly terrible position.

Even with the benefit of hindsight, it is in most cases, impossible to square the circle.

Encyclopedia of The Holocaust – published by Macmillan Publishing Company New York 1990. The Warsaw Diary of Adam Czerniakow, published by Elephant Paperback 1999 The Holocaust – by Sir Martin Gilbert, published by Collins London 1986 Holocaust Historical Society Lodz Ghetto compiled by Alan Adelson and Robert Lapides, published by Viking Penguin 1989. A History of Romania, edited by Kurt W. Treptow, 3rd edition, Iasi, 1997 Wiener Library USHMM Yad Vashem

Copyright: Chris Webb & Robert Raglund H.E.A.R.T 2007

|