Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Ghettos

Siedlce Introduction to the Ghettos of the Holocaust

Jewish Ghettos The Judenrat Judenrat Leaders Prominent Jews

| |||||||||||

Siedlce Ghetto

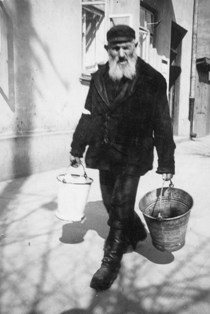

Siedlce was occupied by German troops on 10 October 1939. Before WW2 around 50% of the town's 30,000 inhabitants were Jewish. A few days after the Nazis had occupied the city, on 15 November 1939, they began to arrest Jews.

After gathering them together in a prison, the following day they were marched to Wegrow. There, during the night, around 50 of those arrested managed to escape from the market square, including Hercel Kave and his father. The others were conducted to Ostroleka.

On Jewish holydays German soldiers entered synagogues, beat the Jews who were praying there, tore off their liturgical garments, and fired at those who tried to escape by jumping out of windows. Josef Rubin died thus, on the seventh day of Sukkot.

From the beginning of the occupation the Germans plundered Jewish shops and homes. At the end of November 1939, soldiers entered the synagogue and the Beit Hamidrash (House of Prayer), and threw out the Torah scrolls. In a frenzy of hatred they ripped them apart and trampled on them.

During the night of the 24 - 25 December 1939, the Nazis set fire to the synagogue, homeless Jewish refugees who were inside died in the fire.

At the end of November 1939, the Germans ordered the formation of a Jewish Council – the Judenrat. It included: Icchak Nachum Weintraub – chairman; Hersz Eisenberg – deputy-chairman; Herszl Tenenbaum – secretary, responsible for liaison with the Gestapo; Dr Henryk Loebel – health division; M. Czarnobroda – treasurer; M. Rotbejn – employment division; J. Landau, lawyer – social assistance; A. Altenberg – supplies division; L. Grinberg – legal assistance; R. Leiter – general matters.

There were 25 Judenrat members in all. "The members of the Jewish Council were, in general, recognized Jewish leaders, to whom the Nazis gave enormous power until the moment when they, too, were deported."

The Council managed Jewish property and manpower, and drew up "transport lists" (lists of persons destined for extermination camps). A Jewish police force kept order, wearing as insignia caps of office, nightsticks, and special armbands with the inscription "Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst". There were around 50 of them. Gewisser stood at their head. There was also the Sanitätsdienst – the Sanitation Service. Its purpose was to maintain cleanliness in the apartments, courtyards, and streets of the Jewish quarters.

After the closed ghetto was instituted, the functionaries of the Sanitation Service became part of the Health Division of the Jewish Council. In addition to their previous duties, its members were ordered to assign living quarters for Jews who moved to the already overcrowded ghetto. The Judenrat also had an employment office (Arbeitsamt), whose director was Izrael Friedman.

Unfortunately nearly all these writings have been destroyed. What has been saved is only that which he had published in the press in the interwar period. The function of chairman of the Judenrat was filled not by Weintraub, but by Dr Henryk Loebel. Emil Karpinski remembers that "people fought each other, literally fought, gave bribes, and used every possible means to get a position in the Judenrat or the Jewish police."

The Germans had overall supervision of the labour, and the workers were supervised by SS-men, who controlled the progress of the work. Around 1,500 Jews left the ghetto every day and went to the jobs to which they had been assigned.

In April 1940, the Germans carried out the registration of all Jewish men between 16 and 60 years of age, and in November 1940 a census of Jewish people was conducted for those streets on which they were most numerous.

Within the Siedlce city limits, two quarters were marked off. Quarter I included the streets 1 Maja (now Swirskiego), Orzeszkowej, Kochanowskiego, Stary Rynek (now Ul. Bohaterow Getta), Browarna, Jatkowa (now Czerwonego Krzyza), Targowa (now Czerwonego Krzyza), Aslanowicza, Blonie, and Pusta. It was inhabited by 3,589 Jews and 369 non-Jews, together 3,958 persons. Quarter II included the following streets: Sienkiewicza, Kilinskiego, Przejazd (now the extension of J. Kilinskiego), Asza, Kozia (no longer in existence), Poprzeczna (now Esperanto), Pulaskiego, and Przechodnia (now an extension of J. Kilinskiego). It counted 3,306 Jews and 372 non-Jews, together 3,678 persons. Together, according to the register, Quarters I and II were inhabited by 6,895 Jews. Quarters I and II formed the so-called "open ghetto".

In November 1940, the Judenrat received a new order for a "contribution" of 100,000 zlotys. In December 1940 the number of Jews living in the town amounted to 13,000. During 1940, Jews from the Warthegau were forced to move to Siedlce, and from that year many Jews had to work in forced labour camps within the city. The Germans were also determined not to allow Jews, under the pressure of the existing situation, to change their faith. On 21 February 1941, the administrator of the Siedlce diocese, Bishop Czeslaw Sokolowski, issued a ruling to the Catholic clergy, in which he suspended permission for the baptism of Jews, Muslims, or pagans. He did so under pressure from the authorities of the Generalgouvernement, and in a decree of 23 January 1941, in order to prevent the numerous conversions from Judaism to Catholicism, the Germans decided that it would be the competent starosta or mayor who would make the decision.

The Bishop’s ruling, however, was not too carefully observed, as the Generalgouvernement authorities addressed themselves again to the Diocesal Curia in Siedlce in this matter. In a document of 10 October 1942 they required that "adults be checked at baptism, to find out if they are of Aryan descent."

In March 1941, the Germans organized a 3-day Aktion in Siedlce, during the course of which many Jews were murdered. On 2 August 1941, the Germans issued the decree for the formation of a closed ghetto. The ghetto encompassed almost the entire area of Quarter I.

All the Poles living in this area were given until 8:00 p.m. on 6 August 1941 to leave the ghetto. At the same time, Jews who had lived outside the ghetto’s boundaries were ordered to move into it. In particular this concerned the Jews living in Quarter II. The period indicated for making the move was from 7 - 20 August 1941. On 1 October 1941, the ghetto was closed.

Barbed wire fences were constructed on the streets separating the Jews from the rest of the population. No one was allowed to go in or out without a special permit. After the closing of the ghetto the food and health situation of the Jewish population suddenly grew much worse. Every day many people died:

"At the beginning of the occupation people behaved with compassion towards one another, but with the growth of terror, poverty, and all the "plagues of Egypt", peoples’ hearts became desensitized and even vicious; for a piece of bread or the shadow of hope of saving themselves many served the Germans or persecuted others in various ways. Among others, these included a fairly large number of the Jewish police as well as Judenrat functionaries." For a certain time contact remained between craftsmen in the ghetto – mainly shoemakers – and their business partners on the "Aryan" side. The latter placed orders with the craftsmen, and provided food in payment. The transfer point was a stretch of Sadowa Street. On receiving word of this from an informant, the Germans sealed off the ghetto. In November, Jews from the following localities were moved to Siedlce: Czuryly, Domanice, Krzeslin, Niwiski, Skorzec, Skupie, Stara Wies, Wisniew, Wodynie, Zbuczyn, Suchozebry, and Zeliszew. In March 1942, 12,417 Jews lived within the ghetto precincts.

"15 people lived in rooms of 10 sq. metres... There wasn’t room for everyone, people slept outside, in the corridors... Gestapo functionaries who came into the ghetto asked us ironically if we were receiving letters from our relatives in Russia on the Ladoga River, because at first we did not know where they were transporting the Jewish population."

On 3 March 1942, the Germans seized 10 Jews and shot them at Stok Lacki under the pretext that they had refused to work. Under German pressure, the Judenrat issued a declaration supporting the sentence. In June 1942, Nazis required the Jewish Council to provide a certain number of craftsmen and their machines. At the beginning, the place to which they had been sent was kept secret. Later it turned out that it was the camp at Majdanek.

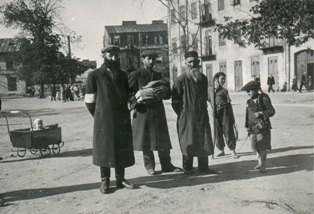

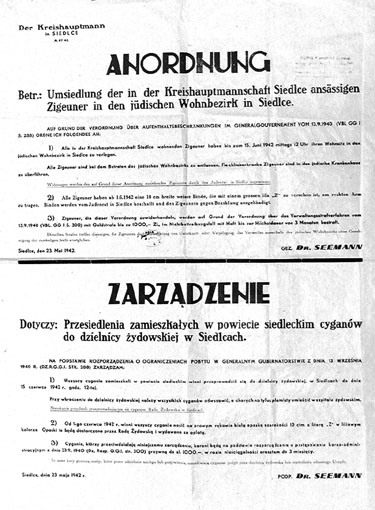

On 23 May 1942, the Gypsies (Roma) who lived in the powiat (county), began to be moved into the ghetto. They were given until 15 June 1942 to move and were required to wear on their right arm a white band with the letter "Z" in lilac. A part of the Gypsy population that had been deported to Platerow and Sarnaki from 10 - 31 December 1940, had stopped in Siedlce and the surrounding area.

These were transports of over 500 people, who had come from the lands annexed to the Reich. In the course of 1941, the German Gypsies (Sinti and Roma) of Cologne and its environs, including Hürth, were transferred to Siedlce. There were at least 326 Gypsies in the ghetto.

Self-defence groups began to form on the basis of acquaintance, or of school, social, family, or political contacts, both within the ghetto and without. In the middle of 1940, the Polish Armed Organisation, whose composition included members of PSL (Polish Peoples Party, called ludowcy) issued a statement in which it was written, amongst other things, that:

"Wherever necessary, in as far as possible help should be given to members of the Jewish nation. The form of help should be dictated by needs on the one hand, and by possibilities on the other, with the aim of making it possible to survive the common danger and common enslavement. Let us remember that after the destruction of the Jewish people, the unpredictable occupiers will commence the complete liquidation of Poles." The penalty for leaving the ghetto without permission was death. The person seized was searched and then shot in a clever fashion: "Usually, between ten and eleven in the evening, the condemned person was taken outside the gates of the ghetto on 11 Listopada St. or Targowa Street. The person would be ordered to run towards the ghetto gate and would be shot in the back. Every day in the evening the inhabitants of neighbouring houses heard shots. The next day the Jewish police collected the bodies of those killed.

The Home Army, as far as it was able, fought against informants who told the occupiers about Poles who hid Jews. In the village of Kolonia Ruda, in the district of Bielany, Eugenia Gajek was shot for having informed on the Karpiński and Rytel families. Fortunately, during the raid that was organized as a result of her information, the hidden Jews were not found. Unfortunately there were also some bad examples: It happened sometimes that the Polish population turned in Jews who had left the ghetto or work camps in search of food. Most often they were turned over to the Polish blue police or the German gendarmes. Those who were caught were most often killed. There were also cases of Polish bandits murdering Jews. Such an incident occurred in Opole Nowe near Siedlce, where in March 1944 over a dozen hiding Jews were killed.

These included Dr Loebel’s son Witold, Roman Głazowski, Lolka Zalcman, Herszko Cygielstein, Leibko Wiśnia, and Romińska. In the village of Trzciniec in 1943 peasants murdered Szmul and Gieńka Krawiec. They were afraid that if the Krawiecs were arrested, they would provide the names of the householders who had helped them, as had happened in the neighbouring village of Jagodne, where a Jew who had been arrested indicated 28 householders who had helped him. They were arrested by the Germans.

It was a false hope. Dr. Fischer deliberately wanted to calm the Siedlce Jewish community. The Aktion Reinhard, whose goal was the final liquidation of the Jews, was already underway. Information about the liquidation of ghettos in other cities and about the transfer of people to the area of Malkinia had already reached the ghetto. On 20 August 1942, the inhabitants of the ghetto received a serious warning. The Germans demanded the immediate provision of several dozen workers for the purpose of unloading railway cars. After the cars were opened it was discovered that inside were the bodies of Jewish men, women, and children, who had come from Radom.

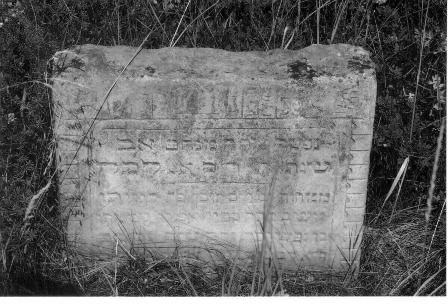

The railway car was part of a "death train" that transported Jews to Treblinka. As a result of a fire the car could not reach its destination. When the workers opened the car they saw around 100 dead bodies – squeezed together and intertwined one with the other. They had all died from lack of air, from the heat, and from the fumes of the quicklime with which the floor of the car was strewn. "Under the rifle butts of the SS-men, the workers had to empty the car. The dead were taken to the Jewish cemetery, where they were buried.

The Germans spread the news that the dead were prisoners being moved to another jail, but no one believed it." The Siedlce Jews saw with their own eyes that deportations were taking place. People wondered - to where? Everyone wanted to believe that it was to somewhere in the east, maybe Smolensk. The name of Treblinka was also mentioned. In the ghetto an atmosphere of uncertainty prevailed.

On Saturday 22 August 1942, in the early hours of the morning, the ghetto was surrounded by the Germans, the Polish blue police and by Ukrainians. Machine guns were set up on the two sides of the main entrance to the ghetto. That day 9,300 Jews from Mordy, Losice, and Sarnaki arrived in Siedlce. The local Jews were told that by 10 o’clock all must come to the cemetery by the burned synagogue.

In addition to the police mentioned earlier, the Jewish police also took part in supervising the execution of this order. The search for those in hiding now began. There were not many of them, since, as Hercel Kave remembers,

"It required both courage and the will to live. However, apathy was understandable. People who had lived for three years without hope, humiliated, were now psychologically exhausted and without any desire for life."

"The people gathered on the square and forced to remain in a sitting position were suffering terribly from lack of water. It was a sunny day. Furman, a member of the Judenrat, as someone who knew German well, stood and made his way in the direction of the main gate where the German officer who was directing the whole operation was standing. He did not manage to reach him however. A few shots rang out and he fell dead. At that moment the crew of one of the machine guns let off a volley, killing those who had tried to stand or were sitting in an upright position.

Around 11:00 a special unit of the "Vernichtungstruppen" ("extermination groups"), composed of Germans and Ukrainians, arrived. There was a short exchange of words between the leader of this unit and the head of the local Arbeitsamt. The former wanted to transport all the Jews; the second, however, wanted to keep a certain number of young men and experts.

Finally, around two in the afternoon, the Germans ordered the men between 15 and 40 to form a line, because they were going to choose those suitable for work. From all sides of the cemetery men ran like wild animals, trampling others underfoot, to the place where the line was formed. In the end, under constant beating by the Gestapo men, the line was formed and began to move forward slowly. The highest ranking Gestapo officer decided who was to live and who to die with a wave of his stick. He asked those whom he had singled out for work about their occupation and looked at their hands, in order that he might not, by accident, let pass a non-worker.

Anyone who showed a paper or document stating that he was a functionary of the Judenrat was directed without appeal to the left, that is, to death. Those who were sent to death were pitilessly beaten along the way.

On the evening of that day the fire department was brought in, and ordered to pour water on those sitting. Another eye witness remembered that "the Gestapo men drank beer at a little table placed on the rubble of the former synagogue. Around them sat the crouching Jews, one next to the other. I saw Dube and other Gestapo men shooting into the crowd of Jews, while drinking beer. The corpses of the Jews that had been shot were collected by the Jewish police and carried by cart to the Jewish cemetery." The history teacher Wasercug was shot on the square, since he spoke to the crowd and asked them to retain their dignity in this last hour. As he was shot he shouted to the Germans, "Your hour will come, vile reptiles!"

There I saw many newly-dug trenches and the bodies of very many persons of Jewish origin. There were the bodies of men, women, and children. The group of Jews that we had brought to the cemetery was made to stand in three lines, in such a manner that the first row stood by the wall, the second kneeled, and the third half lay, half sat. It gave the impression that the group had been placed for a photograph. These Jews were shot with machine guns by three Gestapo men and four functionaries of the Sonderdienst.

Later, these same Gestapo agents and the Sonderdienst functionaries finished off those Jews who lay on the ground with pistol shots. From the prison we brought a group of thirty-some women of Jewish origin. All the Jewish women brought to the Jewish cemetery were shot against the cemetery wall by these same culprits. In contrast to the men, while they were being shot the women shouted, cried, and even tried to resist." "I personally saw how, at the local cemetery, in August 1941 (in fact, 1942) 180 persons who were brought there in three trucks were shot. They were both men and women. Apparently they were accused of being third generation Jews. Among them were the wives of former high civil servants or Polish army officers. Almost all those shot had a prayer book or other object of the Roman Catholic religion with him/her at the time." On Sunday 23 August 1942, around 10,000 Jews were loaded into railway cars and sent to the nearby extermination camp of Treblinka. Florianska Street, through which the columns walked to the railway station, was covered in corpses. From a hiding place, a Home Army photographer took several photographs of the walking column in order to document the extermination of the Siedlce Jews.

Photographs have have also been preserved of the loading of the people into cars, made by a Wehrmacht soldier, Hubert Pfoch, who was passing through Siedlce on his way to the Eastern front. Pfoch recorded what he had seen in his diary:

“From time to time we can hear shooting, and when we get out to see what was going on, I saw, a little distance from our track, a loading platform with a huge crowd of people… all of them were squatting or lying on the ground and whenever anyone tried to get up, the guards began to shoot. Early next morning… we become witnesses of the most ghastly scenes. The corpses of those killed the night before were thrown by Jewish auxiliary police on to a lorry that came and went four times. The guards… cram 180 people into each car, parents into one, children into another… They scream at them, shoot and hit them so viciously that some of their rifle-butts break.” Noach Lasman describes the moment of loading thus:

Pfoch’s account continues: Eventually our train followed the other train and we continued to see corpses on both sides of the track – children and others… When we reach Treblinka station the train is next to us again – there is such an awful smell of decomposing corpses in the station, some of us vomit. The begging for water intensifies, the indiscriminate shooting by the guards continues….” The liquidation of the Siedlce Ghetto was appended to the report of the United Underground Organizations of the Warsaw Ghetto to the Polish government-in-exile in London, and the Allied governments on 15 November 1942. The report was transmitted to the Polish government-in-exile by the courier Jan Karski. After the liquidation, the so-called "cleansing" (the search for hidden Jews) began. Thus in the bakery on Targowa Street, belonging to Jankiel Piekarz, a Sonderdienst patrol under the command of the Volksdeutsche Backenstoss, discovered a group of thirty people. Piekarz’s entire family was hidden there with several of his neighbours.

They had been sitting there for five days. After finding the hiding place Backenstoss opened fire with his machine gun, killing all on the spot. Amongst those killed was Haskiel Trzebucki and his fiancée Franka Piekarz, and the family of Jankiel Dekiel.

In the attic of a house on Aslanowicza Street the Lewin family was uncovered. They were led to the cemetery and shot. By some miracle, Kuba survived. His mother, mortally wounded, covered him with her body as she fell. Kuba lay thus for several hours, and in the early morning escaped from the cemetery.

With the help of friends he hid and obtained false papers. On the grounds of the Jewish bathhouse 50 persons were discovered and killed; in the offices of the Judenrat 20 people, including the family of Efraim Celnik. During the "cleansing" process around 200 people were discovered and murdered, including Przezdziecki and Goldblat. The corpses were collected by groups of Jews, who themselves pulled a two wheeled cart they called an "arba". They pulled it to the gates of the ghetto and loaded the corpses onto a wagon pulled by horses and driven by Poles. It was they who transported the corpses to the Jewish cemetery.

A health clinic was opened, headed by Balfor, the sole Jewish doctor to have survived. A police force was also established, which took care of individual houses and acted as guards and maintainers of order. Its commanding officer was Rubinstein, and after him, Abraham Gessler. "As a lure, the Germans left the little ghetto alone, and people, seeing that there were no more mass killings, began to be attracted, swayed by the rumours that the worst was over and that somehow survival is possible. Life goes on and within the grounds of the little ghetto stands began to open with articles of food and junk for sale. This trade went on through the wires. For rags, shoes, vessels, and Lord knows what else, one received bread, potatoes, and, in general, something to eat." Conditions in the ghetto were terrible; there was a constant insufficiency of water. Some of those who were settled in the ghetto collected the remnants of people’s property, which were sorted. The better things were sent to Germany for the use of those affected by bombing raids, the remainder were sold to the Polish population.

An unknown witness recorded:

They helped believers to celebrate Rosh Hashanah (the New Year) and Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement). The Hassidim formed an "island amongst a sea of inhuman behaviour", where it was considered normal to strip a corpse of everything that might be useful. Lasman describes those days thus: For those who had jumped from the death trains, the ghetto in Siedlce was now the nearest place of asylum. The autumn rains chased people out of the fields; the management of the work camps got rid of those who were unable to work by sending them 'home'."

Over a dozen children were in hiding illegally on the terrain of the ghetto. On 25 November 1942 all of the ghetto inhabitants were moved outside of the town, to the so-called Gesi Borek (the Limanowskiego settlement). The pretext was a supposedly serious outbreak of a typhus epidemic, which might spread to the rest of the town. Those moved were allowed to bring with them only as much baggage as they could carry. The sick and older people were allowed to be carried in carts. The appearance was created that the settlement there of the Jews who had been saved from deportation would be permanent. All the members of the new Jewish Council were given permits entitling them to stay in the place for a period of three months.

"Not far from Gesi Borek was a glass works in which several tens of Jews worked. They lived in the vicinity of the works. Things were brought to them as well that had been smuggled out of the ghetto. During the last two days of the little ghetto’s functioning several carts of items were carried out. The Gestapo and gendarmes 'turned a blind eye', pretending that they did not see what the Jews were carrying out. Naïve people rejoiced that they had managed to trick the Germans. The last days before the move to the new ghetto several tens of people were moved to the glass works, including the old and sick people. They were hidden in a neighbouring barn." – wrote Ida Jom–Tow (Tenenbojm).

Camp I – Army Food Storehouse No. 6 (A.V.L.) This was formed at the beginning of 1940 and liquidated in 1942. It was located in the army barracks. The camp’s terrain covered around 5 square kilometres. The prisoners lived in a two story brick building on the grounds of the former barracks of the 22nd Foot Regiment. On average, around 100 persons worked there. In all, around 5,000 Jews passed through the camp. The prisoners worked on the camp’s grounds, loading wagons with food. During the liquidation of the camp, the prisoners were settled in the little ghetto. Camp II – The Reckmann Construction Firm The name came from the owner, Richard Reckmann. The camp was established in January 1941 and liquidated in March 1943. It was located in the fire-station and two barracks by the railway tracks. The camp occupied around 5 square kilometres. On average around 500 people were living there at any time. In all around 15,000 Jews passed through the camp.

The prisoners worked for the Reckmann firm, building railway lines, working in the railway workshops and at construction sites. An epidemic of typhus and scarlet fever raged in the camp. There was a health clinic. For hard, inhumanely hard, work, the prisoners received 200 g of bread, 1/2 litre of black coffee, and 1 litre of soup consisting of chestnut flour, brukiew (very poor quality vegetables, used as cattle fodder) or beets. The Nazis shot many Jews, and many died as a result of being beaten. There were instances of burial alive at the construction site. The seriously ill were returned to the ghetto. The camp was intended to destroy the people working there, as is proven by the testimony of Srul Mejer, a prisoner of this camp: "Litwak, a dentist from Siedlce, was shot because he walked too slowly to work by one of the Germans supervising us." An eighty-year-old ritual butcher was beaten and trampled by the German guards because he could not manage to unload coal. The badly beaten man died soon after. During the liquidation of the work camp almost all the prisoners were shot. Three prisoners managed to survive; they were Srul Krawiec, Izaak Rafa (?), and Motl Orlanski. The barracks burned down during the struggle for the city in July 1944. Camp III – German Building Inspectorate No. 8 "Kiesgrube" This camp was established in 1941 and liquidated on 14 May 1943. It was located behind the Siedlce-Lukow railway line, by the Lukow road. It occupied a territory of around 2 square kilometres. On average around 300 people, who were housed in two wooden barracks and in railway wagons, were living there.

The prisoners worked in gravel quarries, where the norm was the loading of around 150-200 wagons with sand a day. Food was 250 g of bread and 1 litre of soup. The director of the camp was Inspector Hoppe. There were cases of death by beating or during the loading work. During the liquidation of the camp some of the prisoners died in buildings that the Germans set on fire; the remainder were shot in the Jewish cemetery. Only Leon Kaplan survived. Camp IV – the Wolfer and Göbel Road Construction Camp This camp was established in 1941, and liquidated in October 1942. It was located on Brzeska Street. On average around 2,000 people were imprisoned there. The prisoners lived in 10 wooden barracks. The director was a certain Volksdeutscher named Wasilewski. In all around 20,000 Jews passed through the camp. The prisoners were engaged in road construction work for the Wolfer and Göbel firm, including work on the Brzesc and Siedlce to Warsaw roads and railway lines. This firm was working within the framework of the Organisation Todt. There was an epidemic of scarlet fever in the camp. During the liquidation of the camp the prisoners were moved to the little ghetto. Camp V, the so-called "Bauzug"

This camp was located by the railway station. Around 100 prisoners lived in the camp, residing in railway cars. These prisoners worked repairing railway tracks on the Siedlce to Brzesc line. The director of the "Bauzug" was Walter, a railway man from Wuppertal. This camp was located in barracks by the railway houses. It functioned from 1942 to 14 May 1943. 60 people, who were engaged in unloading building material, lived in it. The director of the camp was a German by the name of Schefner.

In total 17,000 Jews died in the town or were transported to Treblinka. They came not only from Siedlce, but also from the ghettos in the Losice area (from Losice, Huszlewo, Olszanka, and Swiniarow), the Sarnaki area (from Sarnaki, Gorki, Kornica, Lysow), and the Mordy area (from Mordy, Krzesko-Krolow Niwa, Przesmyk, Stok Ruski, and Tarkow). Only a small number managed to hide, but they were in constant danger. The Siedlce dentist, Stanislaw Gilgun, who was hiding in Warsaw, perished during the Warsaw Uprising. Antoni and Stanislaw Górka were discovered and tortured to death in a Gestapo prison. In 1943 the Germans tried to cover the traces of their crimes in Siedlce. With the help of a 40 person group of Jews from Bialystok they disinterred the bodies of the murdered and burned them in piles. For several days the stench of burning bodies hung over the town. After the driving of the Germans from the town, a number of Jews who had survived returned to their homes. Within the territory of the Siedlce powiat there were barely 200 of them. The departing Jews went first to Lodz and then later left for Israel or other countries. After 1968 the children of those who had escaped extermination also left.

Zydzi Siedleccy – Edward Kopowka – Siedlce 2001. Dokumenty i materiały do dziej´w okupacji niemieckiej w Polsce, W. Sobczak, Cmentarz t.2 ; Akcje i "wysiedlenie", cz. I, opr. dr Józef Kernisz.. Warszawa – Łodź – Kraków 1946. s. LXV IPN. Archiwum Państwowe w Siedlcach (APS), Zbiór afiszy okupacyjnych powiatu siedleckiego, Collection of posters, State Archive in Siedlce. Wspomnienia z okresu okupacji- E. Karpinski /w:/ Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego (ŻIH), nr 149 (1989); in: Jewish Historical Museum bulletin, etc. "Żegota" Rada Pomocy Żydom 1942 – 1945, Zegota, 1942 – 1945, A. K. Kunert (opr) Warszawa 2002. Siedlce w okresie okupacji hitlerowskiej w latach 1939 – 1944 /w:/ Społeczeństwo siedleckie w walce o wyzwolenie narodowe i społeczne, Siedlce under occupation, H. Piskunowicz, red. J. R. Szaflik. Warszawa 1991. IPN, Pamiętnik Cypory Jabłoń – Zonszajn ur. w 1915 r. i zamieszkałej w Siedlcach do 1942r., s. 1. Ksero odpisu maszynowego w posiadaniu. autora. Pamiętnik ten został opublikowany przez Agatę Dąbrowską w "Szkicach Podlaskich" nr 9 (2000) Memoires of Cypora Jablon-Zonszajn in collection of Institute of National Remembrance. Relacja Czesław Ulko, z dn. 2.01.1999 r. w posiadaniu autora, testimony, E. Kopowka collection. Wywiad z Barbarą Górską nagrany techniką video w posiadaniu autora, testimony (VHS) E. Kopowka collection. Encyclopedia of The Holocaust – published by Macmillan Publishing Company New York 1990. Robert Kuwalek. Private Collections

Copyright: Edward Kopowka with English translation by L. Biedka. – HEART 2007

|