Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

Ghettos

Izbica Introduction to the Ghettos of the Holocaust

Jewish Ghettos The Judenrat Judenrat Leaders Prominent Jews

| ||

Izbica Ghetto

Izbica a small town nestling in the valley of the river Wieprz – surrounded by the rolling hills of the Roztocze, was probably the most unusual of Jewish shtetls in Poland.

Izbica was established by Antoni Granowski, the Starost of Tarnogora in 1750 as a town designated for the Jews dispossessed by their Christian neighbours.

The town grew rapidly, most notably after 1835 when the new route from Lublin to Zamosc was established through Izbica. Soon the town became an important local centre of trade and crafts outclassing the neighbouring town of Tarnogora after the removal of the Jews.

Until the First World War Izbica was inhabited exclusively by Jews – there was a synagogue and there was no Roman Catholic Church. In fact Izbica remains even today the only town in Poland without a parish church.

During the second half of the nineteenth century the town grew in fame largely because of tzaddik Josef Mordechaj Leiner, the founder of the Izbica – Radzyn Hassidic dynasty that exists in Israel to this day.

During the period between the wars a few Polish families settled down in Izbica, but the Jewish population, mostly impoverished and Orthodox, still exceeded ninety two percent.

According to the popular saying in the Lublin Region Izbica was a Jewish capital – many Jews did not speak Polish and the town remained provincial and relatively poor.

During the Nazi occupation because of the location of the railway line in the middle of the town, Izbica became the biggest transit point in the Lublin Region.

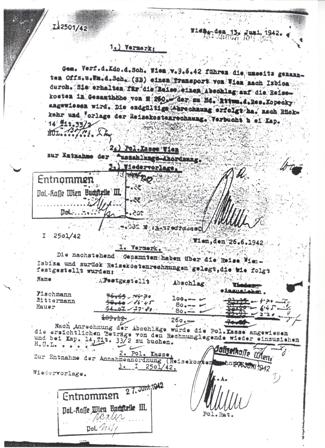

Already in the years 1940- 1941 Izbica became the collection point of many Jews from Lodz, Glowna, Kalisz, Kolo, and even Lublin, but the culmination of traffic cam in 1942 with the commencement of Aktion Reinhard.

Between March and May 1942 some 12,000 – 14,000 Jews from Czech Republic, Slovakia, Germany, Austria were deported there. Most of them were totally assimilated – many had been converted into Christianity even before the war – and found it impossible to adapt to the harsh local conditions.

The Nazis informed them that they were heading East to work, but in Izbica they only found hunger, diseases and terror instead. A lot of Jews died of exhaustion and hunger – the mortality rate was only second to that in the Warsaw Ghetto despite the fact that Izbica was not cordoned off by an impregnable wall.

Although the Jewish ghetto was officially open, the topography of the area made it impossible for outsiders to travel freely.

Thomas Toivi Blatt who was born in Izbica in 1927 – he describes it thus:

“Izbica was a typical shtetl near the city of Lublin in south –eastern Poland. Catholic farmers lived in the hills surrounding the shtetl, but in Izbica itself there were about 3,600 Jews and two hundred Christians. Most townspeople were poor and lived in wooden flats, only a very few, the wealthy, had brick houses. Three artesian pumps and a few wells supplied water. There was no electricity until the mid-1930’s.

A permanent Gestapo command settled in Izbica, it consisted of two psychopathic murderers – Kurt Engels, a noisy and erratic man who was at the time the rank of SS-Hauptscharfuhrer and Ludwig Klemm, a tall quiet non-commissioned officer who spoke excellent Polish and who faithfully followed the dictates of his feared master Engels.

The Gestapo set up its quarters and soon terrorised the whole area, Engels enjoyed shooting Jews in the early morning hours, before breakfast.

On the morning of 24 March 1942 Toivi Blatt recalled:

“Our sleepy town was awakened by shots. Another round up! Frightened Jews quickly dressed, ran and hid. On the hills encircling Izbica, silhouettes of armed soldiers began to appear. The whole area was surrounded. Bands of Ukrainian collaborators rushed into Jewish homes. They took every Jew they encountered – children, old men and women, even cripples.”

From his friend Jozek Bresler Toivi Blatt learned the true destination of the transports and the fate of the Jews from Izbica:

“They are murdered. It is true. They are gassed. Jacek his Christian friend came and told me everything. His Uncle Ryba works for the railway system. Some Jews paid him to follow the transports. He came back and told them the Jews were not taken very far away, maybe only thirty miles to a small village, Belzec. His uncle worked at the station where he saw transports of thousands of Jews arriving every day from different parts of the country, even from Krakow and Lwow.

The train would be directed to a side track where a gate would open, he said, and an area he couldn’t see into, surrounded by a barbed wire fence, would swallow the whole trainload. Then the train would leave empty.

Remember Mr. Kohn’s letter from Kolo – about gassing and burning.” The Jewish population of Izbica shrank considerably. There was an abundance of empty housing, and the synagogue became a warehouse full of confiscated goods from the deported Jewish households.

With the arrival of distant transports into Izbica, Engels cleverly created a Czech Jewish faction within the Judenrat as well as Czech Ordnungsdienst, who were used to remove “inferior Polish Jews” from Izbica.

The Czech Ordnungsdienst were loaded onto the last car of a particular transport, after having participated in the round-up of Polish Jews, where they were taken to Belzec and gassed.

Toivi Blatt remembers the resettlements of Jews from nearby locations:

“In September 1942 all Jews from the small neighbouring ghettos of Krasnystaw and Zamosc were resettled in Izbica. The resettlement was a bloody one. The people had been formed into columns and forced to walk the entire twenty – one kilometres, Engels guarded them with a machine gun manned from the roof of the truck. It was a caravan of horrors. He shot to kill those who lagged behind. Riding alongside in horse-drawn wagons were Ukrainian guards, who executed Jews at will and with pleasure.”

A month later he recalled:

“On 22 October 1942 Engels called the Judenrat and Ordnungsdienst to his quarters – there he announced a deportation order and made the Judenrat and Ordnungsdienst responsible for the successful deportation.

This time everyone, including the Judenrat and the Jewish militia had to go directly to the train station, where Engels personally selected who would stay or go.

What happened at the Izbica train station was horrific:

“Since there were not enough boxcars, Engels decided to make a selection. Everyone was screaming and crying, pushing to be chosen. There was chaos. Engels became furious. As he rested his machine gun on the shoulder of the Judenrat chairman Abram Blatt, he mowed down a group of people and forced the others into the boxcars. They were packed so tightly that some suffocated to death before the train even left town. Those who could not fit in the boxcars, including my family, were told to go home.”

According to testimonies the SS killed around 2,000 Jews during the course of one of the final liquidations of the Izbica ghetto which took place in early November 1942. Before the massacre Jews were crammed into the overcrowded fire station building, where many died, from the lack of fresh air or water.

From the fire station they were taken to the local Jewish cemetery where they were shot and buried in three mass graves. The remaining Jews of Izbica were transported to the death camp at Sobibor during March and April 1943.

Jews from the Izbica transit ghetto were sent to Belzec and Sobibor death camps, and it is extremely difficult to pinpoint with any accuracy where the Jews were liquidated.

According to testimonies and literature the first two deportations from Izbica on 24 March 1942 and 8 April 1942 were sent to Belzec. Most of these victims were Polish Jews, deported from Izbica to make room for the deportees from the west.

The transports of 14-15 May 1942 during which Czech Jews were rounded up, went to Sobibor young men, fit for work went to Majdanek, other deportations were sent to Belzec.

Sources:

From Lublin to Belzec by Robert Kuwalek – published by Ad Rem 2006 From the Ashes of Sobibor by Thomas Toivi Blatt – published by North Western University Press 1997 Records of the Governor in Lublin District – State Archive in Lublin Records of the Judische Soziale Selbshilfe in Izbica and Krasnystaw – Memoirs and testimonies by survivors Private Collection of Robert Kuwalek – Testimonies by Kurt Thomas, Thomas Blatt and interviews with Polish Witnesses from Izbica. Einer kehrte zuruck. Bericht eines Deportieren by A. Hindls – Stuttgart 1965 Martyrologia opor I zaglada ludnosci zydowskiej w dystrykcie lubelskim by T. Berenstein- published by “Biuletyn Zydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego No 21 (1957) Documents, postcard and photographs from the Holocaust Historical Society

Copyright: SP & CH H.E.A.R.T 2007

|