Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

|

|||

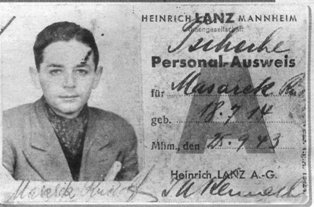

Richard GlazarTreblinka Recalled

We travelled for two days. On the morning of the second day we saw that we had left Czechoslovakia and were heading East. It wasn’t the SS guarding us, but Schutzpolizei, the police in green uniforms. We were in ordinary passenger cars, all the seats were filled. You couldn’t choose – they were all numbered and assigned.

In my compartment there was an elderly couple. I still remember the good man was always hungry and his wife scolded him, saying they’d have no food left for the future. Then on the second day I saw a sign for Malkinia, we went on a little farther.

Then very slowly, the train turned off the main track and rolled at walking pace through a wood.

While we looked out – we’d been able to open a window – the old man in our compartment saw a boy…. cows were grazing and he asked the boy in signs, “Where are we?” And this kid made a funny gesture – draws a finger across his throat.

A Pole?

A Pole. It was where the train had stopped. On one side was the wood, and the other were fields. We saw cows watched over by a young man, a farmhand.

And one of you questioned him?

Not in words, but in signs, we asked, “What’s going on here?” And he made that gesture. Like this. We didn’t really pay much attention to him. We couldn’t figure out what he meant. And suddenly it started: the yelling and the screaming, “All out! -everybody out!” All those shouts, the uproar, the tumult! “Out! Get out! Leave the baggage!”

We got out stepping on each other. We saw men wearing blue armbands. Some carried whips. We saw some SS men – Green uniforms, black uniforms. We were a mass, and the mass swept us along. It was irresistible. It had to move to another place. I saw the others undressing. And I heard: “Get undressed – you’re to be disinfected.”

As I waited already naked, I noticed the SS men separating out some people. These were told to get dressed. A passing SS man suddenly stopped in front of me, looked me over, and said, “Yes, you too, quick, join the others, get dressed. You’re going to work here, and if you’re good, you can be a Kapo – a squad leader.” We were taken to a barracks. The whole place stank.

Piled about five feet high in a jumbled mess, were all the things people could conceivably have brought clothes, suitcases, everything stacked in a solid mass. On top of it, jumping around like demons, people were making bundles and carrying them outside. It was turned over to one of these men. His armband said “Squad Leader.”

He shouted and I understood that I was also to pick up clothing, bundle it and take it somewhere. As I worked I asked him, “What’s going on? Where are the ones who stripped?” And he replied, “Dead all dead!”

But it still hadn’t sunk in, I didn’t believe it. He’d used the Yiddish word. It was the first time I’d heard Yiddish spoken. He didn’t say it very loud, and I saw he had tears in his eyes. Suddenly he started shouting, and raised his whip. Out of the corner of my eye I saw an SS man coming. And I understood that I was to ask no more questions, but to rush outside with the package.

All I could think of then was my friend Carel Unger. He’d been at the rear of the train, in a section that had been uncoupled and left outside. I needed someone – near me – with me. Then I saw him. He was in the second group, he’d been spared too. On the way, somehow, he had learned, he already knew. He looked at me. All he said was, “Richard, my father, mother, brother. “He had learned on the way there.”

Your meeting with Carel – how long after your arrival did it happen?

It was around twenty minutes after we reached Treblinka. Then I left the barracks and had my first look at the vast space that I soon learned was called “the sorting place.” It was buried under mountains of objects of all kinds. Mountains of shoes, of clothes, thirty feet high.

I thought about it and said to Carel – “it’s a hurricane, a raging sea. We’re shipwrecked. And we are still alive. We must do nothing… but watch for every new wave, float on it, get ready for the next wave, and ride the wave at all costs. And nothing else.” Greenery – sand everywhere else. At night we were put into a barracks. It just had a sand floor. Nothing else. Each of us simply dropped where he stood. Half asleep, I heard some men hang themselves. We didn’t react then. It was almost normal. Just as it was normal that for everyone behind the gate of Treblinka closed, there was death, had to be death, for no one was supposed to be left to bear witness. I already knew that, three hours after arriving at Treblinka.

The infirmary was a narrow site, very close to the ramp, to which the aged were led. I had to do this too. This execution site wasn’t covered, just an open place with no roof, but screened by a fence so no one could see in. The way in was a narrow passage, very short, but somewhat similar to the funnel. A short tiny labyrinth.

In the middle of it was a pit, and to the left as one came in, there was a little booth with a kind of wooden plank in it, like a springboard. If people were too weak to stand on it, they’d have to sit on it, and then, as the saying went in Treblinka jargon, SS man Miete would “cure each one with a single pill”, a shot in the neck. In the peak periods that happened daily.

In those days the pit – and it was at least ten to twelve feet deep – was full of corpses. There were also cases of children who for some reason arrived alone, or got separated from their parents. These children were led to the infirmary and shot there. The infirmary was also for us, the Treblinka slaves, the last stop. Not the gas chamber – we always ended up in the infirmary.

It was at the end of November 1942. They chased us away from our work and back to our barracks. Suddenly, from the part of the camp called the death camp, flames shot up. Very high. In a flash, the whole countryside, the whole camp, seemed ablaze. It was already dark. We went into our barracks and ate. And from the window, we kept on watching the fantastic backdrop of flames of every imaginable colour – red, yellow, green, purple. And suddenly one of us stood up. We knew he’d been an opera singer in Warsaw. His name was Salve, and facing that curtain of fire, he began chanting a song I didn’t know:

“My God, my God. Why hast thou forsaken us? We have been thrust into the fire before, But we have never denied the Holy Law.”

He sang in Yiddish, while behind him blazed the pyres on which they had begun then, in November 1942 to burn the bodies in Treblinka. That was the first time it happened. We knew that night that the dead would no longer be buried, they’d be burned.

The “dead season” as it was called began in February 1943 after the big trainloads came from Grodno and Bialystok. Absolute quiet. It quieted in late January , February and into March. Nothing. Not one trainload. The whole camp was empty, and suddenly everywhere there was hunger. It kept increasing. And one day when the famine was at its peak Oberscharfuhrer Kurt Franz appeared before us and told us: “The trains will be coming in again starting tomorrow.”

We didn’t say anything. We just looked at each other, and each of us thought: “Tomorrow the hunger will end.” In that period we were actively planning the rebellion. We all wanted to survive until the rebellion.

The trainloads came from an assembly camp in Salonika. They brought in Jews from Bulgaria, Macedonia. These were rich people, the passenger cars bulged with possessions. Then an awful feeling gripped us, all of us, my companions as well as myself, a feeling of helplessness, of shame. For we threw ourselves on their food, a detail brought a crate full of crackers, another full of jam. They deliberately dropped the crates, falling over each other, filling their mouths with crackers and jam.

The trainloads from the Balkans brought us to a terrible realisation – we were the workers in the Treblinka factory, and our lives depended on the whole manufacturing process that is the slaughtering process at Treblinka.

This realisation came suddenly with the fresh trainloads?

Maybe it wasn’t so sudden, but it was only with the Balkan trainloads that it became so stark to us, unadorned.

Why?

Twenty-four thousand people, probably with not a sick person among them, not an invalid, all healthy and robust. I recall our watching them from our barracks. They were already naked, milling among their baggage. And David – David Bratt- said to me, “Maccabees. The Maccabees have arrived in Treblinka.”

Sturdy, physically strong people, unlike the others.

Fighters?

Yes, they could have been fighters. It was staggering for us, for these men and women, all splendid, were wholly unaware of what was in store for them. Wholly unaware. Never before had things gone so smoothly and quickly. Never. We felt ashamed and also this couldn’t go on, that something had to happen. Not just a few people acting, but all of us. The idea was almost ripe back in November 1942. Beginning in November 1942 we’d noticed that we were being “spared” in quotes. We noticed it and we also learned that Stangl, the commandant, wanted for efficiency’s sake, to hang on to men who were already trained specialists in the various jobs, sorters, corpse haulers, barbers who cut women’s hair and so on.

This in fact is what later gave us the chance to prepare, to organise the uprising. We had a plan worked out in January 1943, code- named “The Time.” At a set time we were to attack the SS everywhere, seize their weapons and attack the Kommandantur.

But we couldn’t do it because things were at a standstill in the camp, and because typhus had already broken out.

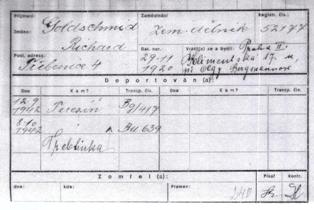

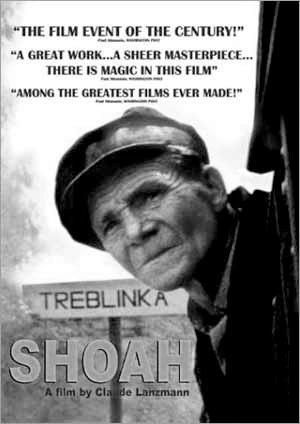

Sources: Shoah – The Complete Text of the Film by Claude Lanzmann, published by Pantheon Books, New York 1985.

Copyright Chris Webb H.E.A.R.T 2007

|