Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| |||||||

The Family Brichta Part One – Backgrounds and Life in Berlin

Hermann Brichta

My father, early days

My Father was very similar in upbringing and outlook to that of my mother. Born on a farm in 1897 among and surrounded by Czechs that is not all that surprising. There were other Jewish farmers in Moravia and Slovakia, ownership of land and equal, or more equal, opportunities, even in the army, were much more and more widely available within the Habsburg empire than in Russian Poland, the latter did not become an independent state until 1919. He was fully aware of his Jewish origins but as a nationality, not as a religion.

Instead the boys were called up, Ernst was killed and by 1915 Oswald and Hermann were Prisoners of War thousands of miles away. It is reasonable to assume that farm labourers too had been called up. With farming then being very labour intensive, horses having been requisitioned and shortage, or absence ,of fertiliser and lack of manure made it impossible to carry on. It seems that grandmother just left the farm unable to cope and moved to Vienna in 1915.

That also meant that when her two sons finally returned from Vladivostok on Russia's Pacific coast and at the terminal of the Trans-Siberian railway, in 1920 and 1921 respectively, they did not return to Vlkoš in Moravia, their birth place, but to Vienna and to their mother. Therese Brichta survived her husband by 18 years. She died of the same sickness, cancer of the stomach.

As I shall explain later, on the two forms he completed in 1919 in Vladivostok, one an application to become a Czechoslovak citizen and the other to join the Czechoslovak army in Russia he, and his brother Oswald in Irkutsk thousand miles and many time-zones away, both put "Jewish" after "nationality" when they could just as easily have put "Czech".

In Germany my father had both German and Jewish friends, boxed at the Maccabi, worked for a Jewish private bank, yet never set foot in a synagogue. He married an equally Jewish woman but at a registry office.

Toni Brichta

My mother Toni and her twin brother Fritz

My mother Toni and her brother Fritz Wasservogel were born on 22.06.1892 in the Kreutzberg district of Berlin. Possibly because they were twins both were very small. They were about ten years old when their father died in 1902 at the age of 52.

Because he had had no life insurance and probably very few savings the children were sent to orphanages although they kept in very close contact with their mother to whom they were devoted. They were also very close to one another.

Fritz went to a Jewish orphanage; I believe it was called the Auerbach, where he received a classical education and where he became fluent in Latin and Greek. I was told that he could translate fluently from one into the other. He was also very good at sports and chess.

Toni, my mother, was sent to a Protestant orphanage where she received a liberal education, became fluent in English and French to interpreter standard and also learned shorthand and typing at a time when girls only gradually entered office work.

This entry into commerce was helped by WW1 when men, who as clerks had carried out such work, had been called up. I have a photo of her with her female colleagues but cannot tell whether that was taken at the offices of the Berlin branch of the Allianz or at the Victoria of Berlin Life offices, she worked for both. I would just like to add that at her Protestant orphanage she was indoctrinated with anti-Catholicism which made a change from anti-Semitism.

It is likely that both of her parents were fully assimilated, thought of themselves as Germans of the Jewish persuasion, were fully aware of their Jewish descent but were not religious. It is also possible that if there was a Jewish orphanage for girls it was an orthodox one and she would not have fitted into it and that a Protestant one was considered a more suitable alternative.

Fritz Wasservogel

My uncle Fritz

I assume that her twin brother, my uncle Fritz, joined the Dresdner Bank straight from orphanage. He too moved in with his mother. The bank had been founded by a Jewish banker but that may not have had any bearing on it.

The First World War interrupted his career there. He joined the German Navy or Kriegsmarine and became a "Vorturner", a physical education instructor, quite something for a small and rather Jewish looking 22-year old.

He had, as already mentioned, been very good at sports and had jumped across roofs at the orphanage, much to the consternation of the staff who called his mother to talk him out of such dangerous pastimes. He was awarded the Iron Cross.

I believe that he was also on a crew operating the "Dicke Bertha", a massive 420mm mortar built by Krupps of which Bertha Krupp was the owner and manager. Probably similar to the way the British Navy was organised where heavy guns were operated by the Marines. That war service and the decoration did not prevent his fellow Germans 28 years later from murdering him in March 1943, having reduced him and his wife to the status of a forced labourer.

Hermann Brichta – From Vienna to Berlin

My father was demobilised in Vienna in 1921 and I have the photo which had been attached to his tramcar pass. His connections with Vlkoš near Kyjov in Moravia where he was born had been severed. As a result of his father's death and certainly as a result of the war the farm had been lost.

Relatives from his mother's as well as from his father's side lived in Vienna. However Vienna in 1921 was a pale image of its pre-war days when it was the hub of a European empire which had vanished.

Though I don't know the exact details and nobody who could recollect them is alive to-day, some of these relatives were in the banking profession and they employed him and sent him as their agent to the private Jewish bank of Siegmund Pincus of Berlin W8, Unter den Linden 49.

Franz Brichta – Birth

I was born on 30 January 1933. This is what I remember of Berlin

I was just over four years old when Hitler was made Chancellor by von Papen on 31.01.1933 and he and his supporters seized absolute power shortly afterwards. That was after years of street brawls between the Communists and the brown shirted SA Nazis.

At the crucial moment the Communists disappeared from the scene and the ballot box. Though I can't remember it myself my mother used to relate on many occasions a graffiti inscription on a brick wall near our villa which asked the pertinent question: "Wo sind die Kommunisten?" (Where are the Communists?). Next day a wit provided the answer: "In der SA" (in the SA).

The street-fighters of the far left, who were not necessarily, committed ideologues and in practical terms there was indeed very little to chose between the two factions, had gone over to the far Right to be on the winning side, they knew the prevailing mood, which was pro-Nazi, and they wanted to be part of it. 12 years later the Nazis of East Germany reverted to being good Communists with equal ease and alacrity.

All I remember of the villa is the garden, the sandpit, the balcony, visiting the caretaker’s wife with my mother after we had left and admiring the polished cuirass cavalry breastplate which the new owners proudly displayed to prove their military family connections when militarism was once again the “in” thing, as if it had ever been anything else in Prussian Berlin.

In this connection I also remember the vast number of people in uniform, another Prussian habit which resurfaced. It wasn't just the brownshirts, the black shirts, the Organisation Todt, a labour battalion, the Hitlerjugend, the B.d.M. (Bund deutscher Mädchen, the female equivalent of the Hitlerjugend), the NSDAP (the National-Socialist German Workers Party) but also the many soldiers, sergeant majors, in field grey.

Everybody seemed to go to bed in their uniforms - it was their everyday casual wear. This was in direct contrast to what my father had told me about the British whom he had encountered in the Far East on his way to Vienna from Vladivostok opposite Japan. He too had been used to the constant wearing of uniforms and riding boots, apparently day and night and on and off horses, in Austria.

The British, he had observed, got into mufti as soon and as quickly as possible. It turned out that the Austrians made poor soldiers in spite of their love of uniforms and the book "The good Soldier Schwejk" a caricature, had much truth in it.

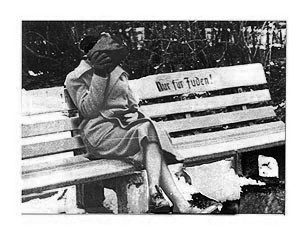

After we had moved into an apartment there were several things I remember. The anti-Semitic cartoons in display cabinets at street corners, the wide pavements, air raid exercises, the cardboard pig in the kitchen, horses and tractors pulling vans and removal vans, the single bench in parks reserved for Jews, the many notices "Juden unerwünscht" (Jews not welcome), the stories of razzias (raids by the Gestapo on establishments to terrorise) and of cardboard boxes containing the ashes of victims murdered in the first batch of concentration camps (KZ) for which the unfortunate recipient had to pay postage.

Also visiting old friends of my mother's who were the beneficiaries of the "WHW" (Winterhilfswerk-help with winter fuel), visiting Aryan acquaintances from my keep-fit class, visiting the KadeWe (Kaufhaus des Westens), a large department store with escalators, my school, selling up, my militaristic toys, from wind-up bomber which could drop bombs fitted with percussion caps to a wind-up submarine which could dive and resurface, that’s what German children played with in the bath rather than with rubber ducks, the favourite of children in less blood-thirsty societies.

I also remember searchlights all along the way from Berlin to the border with Czechoslovakia, my encounter with the Wehrmacht (army) on their manoeuvres, the Saturday morning visit to the newsreel cinema, the Sunday walks, wearing a small Czechoslovak flag on the lapel like a talisman to ward off evil Nazis, which it potentially did.

I also remember the German tenant on the same floor as our apartment who told my mother how glad she was that Germany had left the League of Nations, “Affentheater” (pretentious assembly is my nearest translation, performance by monkeys is another) she called it.

The Cartoons

My earliest personal encounter with anti-Semitism were the horrible cartoons of Jews in the official Nazi propaganda papers, “Das Schwarze Korps”, an SS paper, and “Der Vőlkische Beobachter”, displayed behind glass in showcases fixed at eye level to walls at street corners.

They showed the most ugly Jews with the most enormous noses clad in either Russian-Bolshevik uniforms or with an “Uncle Sam” Stars and Stripes top hat and called Plutocrats, both apparently dominating the world, or trying to, profiting from exploiting good-looking innocent Germans. How unlike the truth!

These cartoons were obviously designed to foster hate but even then I couldn’t work out how one could be both capitalist and communist at the same time. Presumably such double-think was no obstacle to the receptive and empty German mind.

Berlin Pavements

I also remember the wide pavements, necessary because of the population density, laid by hand on a layer of sand to a pattern with small granite cubes, I watched with fascination these cubes being laid to effect repairs.

The Air Raid Exercise

The population density, i.e. the number of people per acre or per hectare, there was little of the detached or semi-detached sprawl with gardens front and rear as is the case in England. Most people lived in apartments and those were large. Apartment blocks had a front building, a rear building and buildings right and left in between with a Hof (courtyard) in the middle.

Those in the front were best off for light because they had the light from the side facing the road and from the back facing the courtyard although there the light can only be described as murky. It could also be noisy. In summer tenants had their windows open.

One of the tenants in our block was a singer and he practiced scales all day. These were old buildings with huge rooms, corridors, bathrooms the size of a small dance floor and huge front gates to the buildings from the road to permit the loading and unloading of the huge German furniture then customary.

Thus my father gave me, though he had a leading share in it, an 0-0 gauge electric train set which was easily accommodated on his large writing desk, including circular and straight rails and a triple shunting section with signals, remote control junctions and transformer.

The room was so large that one didn’t even notice this desk among enormous leather armchairs and equally large sideboards. He also gave me, though it was mostly he who played with it, a Diana air gun and the corridor was long and wide enough to use it there.

One of the uses to which our courtyard was put was a demonstration, around 1935/36, of how to extinguish an incendiary bomb. When the rest of Europe, certainly the former big players France and Great Britain, wanted to disarm or at least have a controlled disarmament. Unfortunately, because they had no stomach for a fight they had allowed Germany to re-occupy the Rhineland in 1936 sending Germany the wrong signal, that of weakness when faced with aggressive bluster such as showing their population how to deal with a phosphor incendiary bomb.

A small phosphor bomb was duly produced, ignited on the ground and extinguished with sand from a ready-to-hand bucket. Appeasement and the British Peace Pledge Union had only whetted the German appetite for more concessions and foreign correspondents duly reported such exercises, as was intended.

A goal for Germany in the propaganda war. Anyway, it was most exciting for an 8-year old boy like me.

The Cardboard Pig

There were other manifestations of preparations for war. We were given, and had to display it on the kitchen wall, a cardboard pig which had written on it “Ich esse” (I eat), a list of waste which had to be separated from other collectible waste to be rendered down for pigswill.

This was done to save foreign currency of which Germany was short because it spent so much, for instance, on the development, construction and production of synthetic fuel plants (BRABAG-fuel from brown coal, the only deposits Germany had) to make it independent of imports in any coming war.

An immense energy also went into the design, development and production of petrol aero engines for fighter planes and bombers and into diesel engines for torpedo boats and into the frames of dive bombers (Stukas, JU 87s), of fighter planes (Me Bf 109 & 110) and of bombers (Heinkels, Dorniers and Junkers).

The Nazis forged ahead with the construction of a new generation of U-boats and torpedoes, massive “pocket” battleships, tanks, the versatile and unsurpassed 88mm anti-tank and anti-aircraft gun, coded radio communication, the “Ultra”, the development of long-distance rockets the sole purpose of which was to kill civilians, they had no military purpose, and the construction of an east-bound autobahn.

The hundreds of thousands of concrete perimeter posts for thousands of large and small prisoner-of-war, slave labour and concentration camps, together of miles of barbed electrified barbed wire and high tension insulators, should not be forgotten.

Even the Volkswagen was a military vehicle, with its air-cooled rear-engine the cold Polish and Russian winter didn’t congeal any oil in an absent sump.

All this feverish but unproductive, in the civilian sense, activity mopped up unemployed labour and was welcome even if the only use to which the output could be used for was war.

The cardboard pig and its swill were the practical outcome of the slogan “Guns before butter” or of the full version “Guns will make us powerful, butter will only make us fat”, coined by Hermann Goering during a radio broadcast in the summer of 1936, himself a fatty.

The Park Bench

Not far from us lived Ida Herlinger who was. related to my father through a common grandfather. My mother and I used to meet old Mrs.Ida Herlinger in the park about halfway between our apartments. Walking on the grass was prohibited anyway but the park had wide paths with benches. Although at that time not entirely excluded from such public amenity altogether, Jews could only sit on one bench, reserved for Jews, somewhere in the middle.

We did sit on it but it was risky, one felt conspicuous, uncomfortable and vulnerable, the object of the exercise. Similarly, when we went to visit her or her daughter’s family who lived close by, and we saw SA men in the distance on our side of the road we would cross over to the other side of the road to avoid a confrontation.

As mentioned, we wore miniature Czechoslovak flags in our lapels to identify us as foreigners to whom the anti-semitic laws did not apply but the protection they offered us was not available to German Jews.

“Juden unerwűnscht”

This sign, that Jews were not welcome, was in the entrance door of all German, as distinct from a few Jewish, restaurants and bars. Not only could that be inconvenient but it signified the exclusion of Jews from the social life and intercourse of their German neighbours and one felt, and was, a second-class citizen.

There were Jewish restaurants, I am not sure of their name, Kempinski was one of them. To ruin that business and stop Jews meeting there the Gestapo made razzias or raids, swooping on the premises and taking everybody away for interrogation and worse.

Cardboard Boxes

Although I was only 8 or 9 years old my mind and feelings for the tensions in the atmosphere were well developed without realising it, our childhood differed from an ordinary, non-Jewish childhood.

I had friends, mainly from school and thus they were Jewish too and whether I visited them or they visited me most of the time the mothers would be present too. We were, after all, quite small and Berlin was a big and dangerous place. Thus one either couldn’t help overhearing their conversation or did so deliberately, children are nosey.

Thus I overheard something that has stayed with me even if I didn't may be appreciate the full meaning of the subject matter. That was that where Jewish men had been arrested, either picked up on the street, at home or at work when they still had work, cardboard boxes would be received by the wife or family with a note that they contained the ashes of their husband, father or brother who had died of a heart attack or had been shot while trying to escape, neither likely. This ordeal was made worse by the recipient having to pay the postage due on the parcel.

On Manoeuvres

Another manoeuvre I witnessed took place near Berlin. According to what my mother wrote on the back of a photograph. I started school at the age of 6½ which makes it April 1935. So may be it was during the summer holidays of that year that a clerk in my father's bank, who was to play an important part later, invited men to stay with him and his wife on their smallholding just outside Berlin. They had no children of their own and made a fuss of me.

We had a photograph of myself being decked out by them as a Red Indian with a head ornament made with chicken feathers and a large string of conkers round my neck.

We went rabbit shooting too but it soon became clear that I couldn't stand the noise of the report of the gun. In fact my father had given me a small replica of a fine looking and fully working six-shooter starter pistol firing blanks which I never used.

The significant experience of my visit was the German infantry, then on manoeuvres in the district. I was then a fair-haired Aryan-looking little boy with authentic Lederhosen and they took to me. Seven years later, in their first foray into Eastern Europe, into Poland to start with, they would kill Jews, children, men, women , the old, wholesale and a year after that would do the same in Russia.

However, as they were unaware that they were dealing with a Jewish boy and believing that I was German they were keen to show me all about their rifles, how to take them apart, put them together again, load them with cartridges, unload them, apply and remove the safety catch and also their Gulaschkanone, or field kitchen, with its folding chimney stack and large cauldron on wide wheels.

At some time during this friendly banter one of them held me and pretended to undo the seam of my Lederhosen with his bayonet and, naturally, I felt a bit uneasy about that. So I told them that I was a Czech. I had been told to say that I was a Czech, i.e. a foreigner and therefore exempt for the time being from intimidation, whenever I was in an unsafe, threatening or uncomfortable situation and by 1935 there were many such.

Dachau (opened 22 March 1933) and Oranienburg- Sachsenhausen had been well established, the one-day boycott of Jewish shops, and Jewish doctors' and lawyer's consulting rooms on 1 April 1933 had only been a start.

Violence was firmly established.. "Wenn's Judenblut vom Messer spritzt dann gehts nochmal so gut" (When Jewish blood spurts from the knife everything gets better and better) was a familiar ditty sung by the Hitlerjugend and even if its full significance may have eluded me its threatening tone didn’t.

The strain of arrests, torture and deaths was beginning to tell as were the difficulties encountered when trying to escape it by emigration and, as it was all-pervading, even children were aware of it. So I said my get-out clause available, exceptionally, to me but not to other Jewish children, and that didn't half upset the applecart.

To the soldiers it meant that secrets had been divulged to a lowly Slav and a most likely future enemy, the “Drang nach Osten”, the drive towards the East, was official policy. All very embarrassing. So they asked me never to tell anybody what I had been shown.

The Newsreel Cinema

In fact only 17 years after Versailles war was once more never far from one's mind and vision. Before Jews were forbidden such visits, every Saturday morning I used to go with my cousin Ernst to a newsreel cinema.

It got us out of the apartment. The newsreel cinema had the advantage of variety, Laurel and Hardy (Dick und Dof in Berlin slang) Mickey Mouse, Popeye the spinach-eating sailor and his girl friend Olive Oil, a short Western in which the Redskin invariably bit the dust, something that disturbed me, I didn’t like violence, a science fiction short film and one or two newsreels, Pathé comes to mind.

Of the latter I remember seeing small Japanese open canopy bombers dropping bombs on Manchurian cities. In those days Japan had invaded Manchuria (1933). Around that time Abyssinia had been likewise bombed and invaded by Fascist Italy and had appealed, fruitlessly, to the League of Nations. May be we saw some of that too.

War may not yet have been broken out in Europe but it had elsewhere. The Japanese were considered to be honorary Aryans because, although definitely non-German in looks, they had the aggressiveness and expansionist outlook and the ruthlessness and barbarity in achieving their aim, aspects which the Germans admired and emulated.

When the Germans sent their Condor legion to Spain to help Franco and gain experience in low-level bombing of cities full of civilians, of which Guernica is the known example, the planes and bombs were bigger but the principle remained the same.

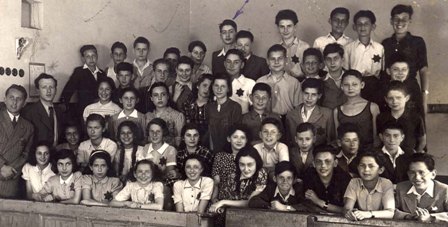

School Days

Our parents had enrolled us at the Joseph Lehmann Schule, a school founded and run by the Jűdische Reformgemeinde, the Jewish Reformed Community, to offer an education to the many who had been expelled from the local state schools or where their stay had been made impossible by bullying, threats and intimidation by their German classmates and teachers alike.

The school was located on the Joachimstaler Strasse, a side street off the wide and well-known Kurfűrstendam, close to the KaDeWe and the Kaiser Wilhelm Gedächtniskirche, the church built in honour of the first emperor of Germany and bombed during the war.

I understand that the school had been an old people’s home. It was large, had a wide marble staircase, a very large Aula, really an assembly hall with raised podium and rows of fixed seats, with an organ halfway up one wall and a large and well equipped sports hall.

As already mentioned, apartment buildings in Berlin consisted of two parts, the more desirable building at the front facing and parallel with the main road, and the more second-class building behind the front one and separated from it by a Hof or courtyard. The Joseph Lehmann Schule was the rear building of such an arrangement and the courtyard was the schoolyard and far too small for the hundreds of children.

We were also surrounded and overlooked by neighbours who were probably not kindly disposed towards Jews. To enable the children to at least stretch their legs during breaks one was only allowed to walk sedately in the courtyard in an anti-clockwise direction and, so as not to upset the aforementioned neighbours, one had to be quiet.

A former schoolmate wrote to me reminiscing that one could only walk in pairs. I had forgotten that. I would rotate with my best friend Bernt Schwarz who would also visit me frequently at home. He and his older brother Hans Heinz, who was also a pupil at that school, emigrated with their parents on time and I met Bernt in London in 1948 through my cousin Ernst who had bumped into him.

Not all that surprising because Ernst, I, and Bernt’s parents lived within a stone’s throw of one another. Bernt was then doing his National Service in the Royal Air Force (RAF) and proudly wearing his uniform. He told me then that his brother had served in the RAF’s Bomber Command and had been shot down and killed.

The school also had a fully and newly equipped large Turnhalle (gym) with climbing ropes and steel tubes hanging from the ceiling, Swedish ladders along the wall, huge leather cushions, leather upholstered horses to jump over and parallel bars. I liked gymnastics and climbing, from former classmates I now know that some hated it in equal measure.

One of the peculiarities of the school was that boys clicked their heels in true Prussian fashion when greeting a teacher but we drilled to Hebrew/Ivrit commands using British drill, i.e. as one would have done in British-mandated Palestine.

My first year’s teacher was Frau or Fräulein, Miss or Mrs., I don’t know which, Brigitte Brasch. All I remember of the class is that we modelled animals in plasticine and that some of my classmates were very good at that and showed artistic promise. I wasn’t among them.

I could read before I started school and my mother spent hours going over the multiplication tables with me and, while I have forgotten most of my German and must have recourse to a dictionary when writing in that language, much of my counting is still done in German.

Likewise I remember, and can still recite, the poems I learned there. We learned two types of writing at the same time, German Gothic script and Roman script and books too were printed in either. The Nazis preferred Gothic as it set them apart from the rest of Europe and, for that matter, from the rest of the world

In my second and third year, which I didn’t complete, our class teacher was Herr Erich Spieldoch. Of the four fellow classmates whom I found in 2003, two boys now in Australia, two girls now in Israel, the two girls disliked him heartily. I got on alright with him except for the last day.

Herr Spieldoch was extremely gifted. He played the organ, taught us modern Hebrew and his teaching of proportions in arithmetic has stayed with me ever since as have, as I said, the poems and literature he taught. He was a strict disciplinarian.

On my last day at school before our emigration he had my school report ready. I was naturally not at my best, apprehensive of what the future held in a country I didn’t know, whose language I didn’t speak, to be torn from a reassuring routine. My writing that day, for which I used to win praise, was not up to the usual standard, the stress showed, quite understandably.

He crossed out the mark he had given me for handwriting and substituted a lower one. Not the thing to do to a child of 9 who may have to present the report to his next school. I haven’t got the report any more but I remember, word for word, his general comments: “Franz muss bescheidener werden in dem er seine vorlaute Art ablegt”. (Frank must become more modest by getting rid of his cheeky/impertinent manner).

That may have been his true and sincere opinion and best advice but whether one should burden an imminent emigrant with such character criticism is another matter. Naturally, the report never mattered.

My next school, the Jewish school in Prague, was glad to have me and, in fact, I was quiet and inhibited. The repressive atmosphere in Berlin and the unfolding tragedy in Prague didn’t really make for exuberance and Jewish children in both places were denied this aspect of a normal childhood.

The school, as already mentioned, was the product of its time and so was its library. On a page of one of its newsletters provided by a Berlin archive there is a list of teachers and their classes for the 1936 term. There is also a note on donations of a large number of scientific and educational books brought about by emigration.

The teachers’ library stood at 1,500 volumes, consisting mainly of fiction and poetry (belletristisch) and the books available to various classes amounted to 500 volumes, among them valuable reproductions of paintings.

There was also a collection of 2,500 pictures covering the disciplines of geography, natural history and the history of art. To that could be added 1,100 stereoscopic pictures with an apparatus to view them. All of this was looted later when the school was finally closed in June 1942. Much of it may well exist in German homes.

Meeting the Brichta family in Slovakia

In 1936, when I was 7½ we went to Trenčianské Teplice, or Trenschien Teplitz in German, a holiday resort in Slovakia where I met the Slovak part of the Brichta family.

The hotel was on top of a steep, rocky hill accessible by a steep road and yet it had a swimming pool where I learned to swim. Only breast stroke and I haven’t progressed since and now that I swim in the sea off England’s East coast off Aldeburgh I am often reminded of that event. It was there that I met a little girl a year younger than me, Erika Brichta, who became the only survivor of the whole of that side of her family.

She was thrown from the train which took her parents to Auschwitz, was picked up by a Slovak peasant and rescued. After the war she went to Vienna where she was brought up by the only surviving member of her family from her mother’s side, her grandmother. Hence she knows very little about her family from her father’s side.

Pre-Emigration Concerns

The continuing appeal of the school can possibly be explained by it being a place to escape to, an oasis, free from the tensions surrounding one at home. At home, quite apart from the reduced circumstances families faced because the breadwinner had been thrown out of his job whether as employee or employer, there was the constant and increasing preoccupation with emigration and the tardiness by foreign consulates to reply when time was really of the essence.

Could one leave one’s parents behind, for instance. The grandfather of one of my schoolmates was a pharmacist and took an overdose to remove the problem from his children. Where could or should one attempt to emigrate to? Was it better to wait for a visa from a country with better prospects, as far as one could tell that from Berlin (or any other part of Germany), or grab what was available, or wait somewhere, just anywhere, until the right visa came along as that was beyond the reach of the Germans, even if that was in war-torn Japanese-occupied Shanghai?

Around 17,000 German, Austrian and Czech Jews fled to Shanghai. It was a “free” port and, for reasons best known to themselves, the Japanese respected that, no entry visa was required. It was however tropical, had the monsoon rain, tropical diseases unknown to European Jewish doctors, German furniture and clothing was quite unsuitable and water had to be boiled.

Those with relatives abroad fared best but few had those. An earlier Germany which had permitted and encouraged emancipation had made for few emigrants, unlike the pressure and pogroms in Russia and Poland which had fuelled emigration as soon as railways, steamships and the growth of the United States had made that possible in the 19th century.

Could one find a guarantor, an affidavit, how could one find the money demanded by the German authorities, in US dollars, for an exit visa, a source, like everything Jewish, of income by the state by extortion?

Should one learn a trade? One’s professional status, certainly in medicine and law, was not recognised abroad and there would be neither time nor money to go through the lengthy process of re-acquiring them there. Should one learn a language and if so, which one? For Argentina one needed Spanish, for Brazil Portuguese, for areas then coloured pink on the world atlas it was English.

For those who wished to remain in Europe, a choice they came to regret, it was anything from Dutch to French to Flemish to Danish. A difficult choice considering one didn’t know where one would end up, if anywhere. My uncle Fritz had a visa for Haiti, that is how desperate people were. It came too late, he and his wife perished in Auschwitz in March 1943.

Emigration was certainly not a matter of choice and of packing up and going. The USA was a particular bastion of resistance to Jewish immigration with a limited quota of annual visas per country which took no notice of the seriousness and plight of our situation. “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” (Emma Lazarus, inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty) did not apply if the huddled masses happened to be Jews being persecuted by Germans after 1933.

I know the details of an acquaintance in Prague, the same applied everywhere else. Thus Dr. Gottfied Bloch, MD and his parents sought entrance into the USA in 1938 after the Munich crisis when they had fled from the Sudeten to Prague.

His visa was not issued until 1955. In the meantime he went through the ghetto of Theresienstadt, the family camp of Auschwitz where inmates knew in advance that they were going to be gassed, a death march and the concentration camp of Buchenwald. His parents were killed in Auschwitz.

He survived only because he was a doctor and then only just. Israel, or Palestine as it then was or one side of the river Jordan only, was for all practical purposes closed to Jewish immigration by the pressure exerted by the Palestinians on the British and willingly succumbed to. England was, very late in the day, opened to children but not to their parents, turning nearly 10,000 of them into instant orphans.

Selling Up

The last days in Berlin were disturbing. On the one hand one left behind, or so one hoped, the menace of the Nazi persecution and the pro-Nazi population, on the other hand one also went into the unknown.

I had had private lessons in Czech with an elderly man who also taught Czech to the Berlin police. They knew where they were going even if the rest of the world didn’t or didn’t want to, but it was pretty useless using an old-fashioned textbook dealing with cockerels and horses, more or less on the lines of la plume de ma tant.

Obviously my parents prepared for the move as much as possible and decided that the future lay in a very small apartment and all of the furniture was sold. Not only furniture but also much of our Dresden and Rosenthal china and the contents of our vitrines or display cases of things one was proud of.

I particularly remember staring at and admiring two large groups of painted porcelain figurines of Prussian porcelain manufacture with the sign of the two crossed curved sabres on the underside. They were of musicians. The delicacy and accuracy of the miniature piano, violin, bow and flute, the infinite number of tiny holes of the exquisite protruding cuffs of the period costumes, the faces, the white of the porcelain and the accurately delineated vivid colours were astounding.

They were works of art for which my mother, who dealt with the sale of the household, got nothing. I still remember the dealer telling her that, as so many Jews were leaving and selling up, the bottom had dropped out of the market.

Thus the German Berliners, and the same happened all over Germany, had not only benefited from Jewish shops, jobs, surgeries, factories, businesses and official appointments at schools, universities and hospitals, they now could get their valuables for a song too.

Rabid anti-Semitism paid rich dividends.

Sources: The unpublished memoirs of Frank Bright – Selected extracts used with full permission. Dedicated to Hermann and Toni Brichta – Both murdered in Auschwitz "Produced by Chris Webb" Online version: Copyright H.E.A.R.T 2008

Copyright. Frank Brichta H.E.A.R.T 2008

|