Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| ||||||||||||

Men Record their Experiences of the Holocaust

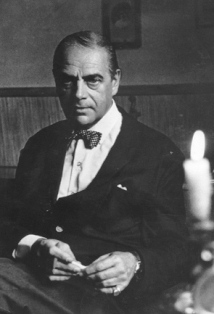

Hugh Greene

Daily Telegraph correspondent in Berlin during 1938

“I was in Berlin at that time and saw some pretty revolting sights – the destruction of Jewish shops, Jews being arrested and led away, the police standing by while the gangs destroyed the shops and even groups of well-dressed women cheering.

Maybe those women had a hangover next morning, as they were intoxicated all right when this was taking place. I found it, you know, really utterly revolting. In fact to a German journalist who saw me on that day and asked me what I was doing there, I remember I just said very coldly, “I’m studying German culture.”

Sigmund Weltlinger

Member of the Berlin Jewish Council Sachsenhausen – Oranienburg 1938

“But when I came to Sachsenhausen – Oranienburg camp outside Berlin I was immediately taught different. We were all shoved together with clubs and blows and had to stand in even ranks to be counted. Because I had been a soldier I didn’t find that all very difficult but the others who didn’t fall in quickly were beaten immediately.

The most terrible thing was when somebody grabbed hold of a big, strong man and he said, ‘Don’t grab me.’ The guard said, ‘What I shouldn’t grab you?’ and he gave him a blow and this man was immediately over-powered by three SS people.

A block was brought and he was bound fast to it, and the camp commandant said he was sentenced to twenty-five lashes. Then a giant man came, an SS man with a huge ox-whip, and started to beat him. At first the man only groaned a bit but then he begged them to stop.

The commandant said, ‘What do you mean, stop? We’ll start all over again from the beginning.’ But after three more lashes the blood was spurting already and salt was rubbed in the wounds or pepper, I don’t know anymore.

The man was dragged away, unconscious or dead. We never saw him again.”

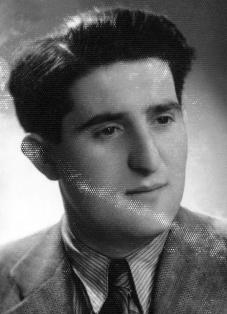

Dawid Sierakowiak Lodz Ghetto September 10 1939

“The first manifestation of the German presence: Jews are being seized to do digging. An elderly retired professor, a Christian who lives in no.11, warned me about going into town, a decent man. What should I do now?

Tomorrow is the first day of school; who knows what’s happening to our beloved school. My friends are all going to attend, just to see what’s going on. But I have to stay home. I must. My parents feel they don’t want to lose me yet. Oh, my beloved school. Curse the times I complained about getting up early or about tests. If only those times could return!”

Avraham Kochavi Lodz ghetto and Auschwitz survivor

“We ran out of food in the house and one day my mother, may her soul rest in peace, asked me to go down to the bakery and stand there the whole night in order to get a loaf of bread the next day.

I got up in the middle of the night and went down to get in the queue. When I arrived there were already masses of people standing in line. At dawn a Pole, who was volksdeutsche – ethnic German arrived with a rifle slung over his right shoulder, a band with a swastika on his left arm.

He was supposed to keep order so that everyone should receive bread. Among us there were children, non-Jews, Poles, running around. They dragged that same volksdeutsche over and pointed at each person saying, “That’s a Jew, that’s a Jew – Das Jude, das Jude, Jude” – so that these people would be taken out of the line and not get bread.

My turn came. I turned and saw that the boy was a friend with whom I played. I said to him in Polish, “What are you doing?” His answer was, “I am not your friend, you are a Jew, I don’t know you.”

That same German with the swastika band was standing before me. I saw that he was a neighbour of ours and I spoke to him in Polish. His answer was in German: “I don’t know Polish, I don’t know you.”

He forcefully took me out of the line where I was waiting for bread and slapped me.”

Dr Zygmunt Klukowski Forced Labour Conditions Szczebrzeszyn

23 July 1940

“The worst consists of digging ditches to drain the marshes. They have to work standing in water. They are really badly fed because their families can rarely afford to send them food.

They sleep in terrible barracks amidst filth – with a complete lack of space. The barracks are several kilometres from the places of work, and they have to walk this distance every day, and are continuously beaten.

They are plagued with lice, some of their clothing looks as if it has been sprinkled with poppy seeds. I was able to see it for myself as there was an epidemic of typhus and all the sick from the work camps were sent to me.”

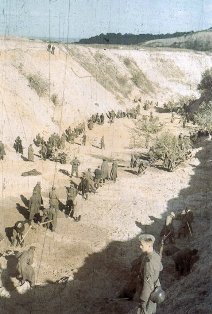

Kurt Werner Sonderkommando 4a Babi Yar – 29 & 30 September 1941

“That day the entire Kommando with the exception of one guard set out at about six o’clock in the morning for these shootings. I myself went there by lorry. It was all hands to the deck. We drove for about twenty minutes in a northerly direction.

We stopped on a cobbled road in the open country. The road stopped there. There were countless Jews gathered there and a place had been set up where the Jews had to hand in their clothes and their luggage.

A kilometre further on I saw a large natural ravine, the terrain there was sandy, the ravine was about 10 metres deep, some 400 metres long, about 80 metres wide across the top and about 10 metres wide at the bottom.

As soon as I arrived at the execution area I was sent down to the bottom of the ravine with some of the other men. It was not long before the first Jews were brought to us over the side of the ravine.

The Jews had to lie face down on the earth by the ravine walls. There were three groups of marksmen down at the bottom of the ravine, each made up of about twelve men. Groups of Jews were sent down to each of these execution squads simultaneously.

Each successive group of Jews had to lie down on top of the bodies of those that had already been shot. The marksmen stood behind the Jews and killed them with a shot in the neck.

I still recall today the complete terror of the Jews when they first caught site of the bodies as they reached the top edge of the ravine. Many Jews cried out in terror. It’s almost impossible to imagine what nerves of steel it took to carry out that dirty work down there. It was horrible……

I had to spend the whole morning down in the ravine. For some of the time I had to shoot continuously. Then I was given the job of loading sub-machine gun magazines with ammunition. While I was doing that, other comrades were assigned to shooting duty.

Towards midday we were called away from the ravine and in the afternoon I, with some of the others up at the top, had to lead the Jews to the ravine. While we were doing this there were other men shooting down in the ravine. The Jews were led by us up to the edge of the ravine and from there they walked down the slope on their own.

The shooting that day must have lasted until 17.00 or 18.00 hours. Afterwards we were taken back to our quarters. That evening we were given alcohol (schnapps) again.”

Wilhelm Findeisen Einsatzgruppen C member September 1941

“I was told that the whole operation and the van itself were secret. It was expressly forbidden to photograph the vans and I was ordered not to let anyone near the van. I then joined Sonderkommando 4 in Einsatzgruppen C.

The van was not used immediately when we arrived in Kiev. When we first arrived they were only carrying out isolated actions. Being a driver, I had nothing to do with these isolated actions.

One evening several officers appeared and ordered certain people to go with them. They went into a private flat where they picked up a professor and his daughter. These people were then taken to a spot close to a piece of open land where a grave was dug.

The people, the officers then gave orders for these two people to be shot. One of the officers said to me, “Findeisen shoot these people in the neck” I refused to do this as did the other men. The girl must have been about eighteen or nineteen. The officer shot the people himself, as the others refused. He swore at us and said we were cowards, but apart from that he did not do anything else.

The gas-van was used for the first time in Kiev. My job was simply to drive the van. The van was loaded at headquarters. About forty people were loaded in, men, women and children. I then had to tell the people that they were being taken away for work detail.

Some steps were put against the van and the people were pushed in, then the door was bolted and the tube connected…. I drove through the town and then out to the anti-tank ditches where the vehicle was opened. This was done by prisoners - the bodies were then thrown in the anti-tank ditches.”

Walter Burmeister Gas Van Driver Chelmno (Kulmhof) Death Camp

“As soon as the ramp had been erected in the castle, people started arriving in Kulmhof from Litzmannstadt in lorries. The people were told that they had to take a bath, that their clothes had to be disinfected and that they could hand in any valuable items beforehand to be registered.

On the instructions of Kommandofuhrer Lange I also had to give a similar talk in the castle to the people waiting there – how often exactly I can no longer say today. The purpose of the talk was to keep the people in the dark about what lay before them.

When they had undressed they were sent to the cellar of the castle and then along a passageway on to the ramp and from there into the gas-van. In the castle there were signs marked “To the baths.”

The gas-vans were large vans about 4-5 metres long, 2.20 m wide and 2m high. The interior walls were lined with sheet metal. On the floor there was a wooden grille. The floor of the van had an opening which could be connected to the exhaust by means of a removable metal pipe.

When the lorries were full of people the double doors at the back were closed and the exhaust connected to the interior of the van. The Kommando member detailed as driver would start the engine straight away so that people inside the lorry were suffocated by the exhaust gasses.

Once this had taken place, the union between the exhaust and the inside of the lorry was disconnected and the van was driven to the camp in the woods where the bodies were unloaded.

In the early days they were initially buried in mass graves, later incinerated. I then drove the van back to the castle and parked it there. Here it would be cleaned of the excretions of the people that had died in it. Afterwards it would once again be used for gassings.

I can no longer to say today what I thought at the time or whether I was too influenced by the propaganda of the time to have refused to have carried out the orders I had been given.”

Wladyslaw Szpilman “The Pianist” Warsaw Ghetto

“Once when I was walking along by the wall, I came across a ‘smuggling operation’ being carried out by children. The actual operation seemed to be over. There was only one thing left to do. The little Jewish boy on the other side of the wall had to slip back into the ghetto through his hole, bringing with him the last piece of booty.

Half of the little boy was already visible, when he began to cry out. At the same time loud abuse in German could be heard from the ‘Aryan.’ I hurried to help the child, meaning to pull him quickly through the hole.

Unhappily, the boy’s hips stuck fast in the gap in the wall. Using both hands, I tried with all my might to pull him through. He continued to scream dreadfully. I could hear the police on the other side beating him savagely. When I finally succeeded in pulling the boy through the hole, he was already dying. His backbone was crushed.”

Tadeusz Pankiewicz Eagle Pharmacy Harmony Square Krakow 6 June 1942

“The scorching sun is merciless; the heat makes for unbearable thirst, dries out the throats. The crowd was standing and sitting; all wait frozen with fright and uncertainty. Armed Germans arrived, shooting at random into the crowd. Then the deportees were driven out of the square, amid constant screaming of the Germans, merciless beating, kicking and shooting.

Old people, women and children pass by the pharmacy windows like ghosts. I see an old woman of around seventy years, her hair loose, walking alone, a few steps away from a larger group of deportees. Her eyes have a glazed look; immobile, wide open, filled with horror, they stare straight ahead. She walks slowly, quietly, only in her dress and slippers, without even a bundle, or handbag.

She holds in her hands something small, something black, which she caresses fondly and keeps close to her old breast, it is a small puppy – her most precious possession, all that she saved and would not leave behind.

Laughing, inarticulately gesturing with her hands, walks a young deranged girl of about fourteen, so familiar to all inhabitants of the ghetto. She walks barefoot, in a crumpled nightgown. One shuddered watching the girl laughing, having a good time. Old and young pass by, some dressed, some only in their underwear, hauled out of their beds and driven out. People after major operations and people with chronic diseases went by.

Across the street from the pharmacy, out of the building at 2 Harmony Square, walks a blind old man, well known to the inhabitants of the ghetto, he is about seventy years old, wears dark goggles over his blind eyes, which he lost in the battles on the Italian front in 1915 fighting side by side with the Germans.

He wears a yellow armband with three black circles on his left arm to signify his blindness. His head high, he walks erect, guided by his son on one side, by his wife on the other. He should be that he cannot see, it will be easier for him to die, says a hospital nurse to us. Pinned on his chest is the medal he won during the war. It may, perhaps, have some significance for the Germans. Such were the illusions in the beginning.

Immediately after him, another elderly person appears, a cripple with one leg, on crutches. The Germans close in on them; slowly, in dance step, one of them runs toward the blind man and yells with all his power: Schnell! Hurry! This encourages the other Germans to start a peculiar game.

Two of the SS men approach the old man without the leg and shout the order for him to run. Another one comes from behind and with the butt of his rifle hits the crutch. The old man falls down. The German scream savagely, threatens to shoot.

All this takes place right in the back of the blind man who is unable to see, but hears the beastly voices of the Germans, interspersed with cascades of their laughter. A German soldier approaches the cripple who is lying on the ground and helps him to rise. This help will show on the snapshot of a German officer who is eagerly taking pictures of all scenes that will prove ‘German help in the humane resettlement of the Jews.’

For a moment we think that perhaps there will be at least one human being among them unable to stand torturing people one hour before their death. Alas, there was no such person in the annals of the Cracow ghetto. No sooner were they saturated with torturing the cripple than they decided to try the same with the blind invalid. They chased away his son and wife, tripped him, and rejoiced at his falling to the ground. This time they even did not pretend to help him and he had to rise by himself, rushed on by horrifying screaming of the SS men hovering over him.

They repeated this game several times, a truly shattering experience of cruelty. One could not tell from what they derived more pleasure, the physical pain of the fallen invalid or the despair of his wife and son standing aside watching helplessly.”

Abraham Krzepicki Jewish ZOB Fighter who escaped from Treblinka death camp after 18 days 25 August 1942

“We still hoped that some kind of separation would take place at the Umschlagplatz and we would be able to show our papers. But unfortunately we never had that chance. As we came closer, we saw the boxcars ready for us and we said to each other, “Oy vey, we’ve had it! We’re in trouble.”

And in fact, the Lithuanian guards came straight over to us and started hitting us over the head with whips; they did not let anyone go near the Germans. From the Umschlagplatz we were moved towards the box-cars. Only two foreman from Waldemar Schmidt’s shop managed to get through; they were in uniform and army caps. They went up to the Scharfuhrer, who was the old sadist, but he had a sudden inspiration. He looked them up and down for five minutes, then nodded and told them they could go.

This was how these two men got away, but nobody else was that lucky. We were moving closer to the box-cars, already we could see elderly people stretched out on the floor of the first car, half- unconscious. We didn’t like the look of this. Then steps were moved up to the box-cars and the Lithuanian auxiliaries started driving us faster with their whips, up into the cars.

We had to give up all hope of being able to show our papers to somebody and so we got into the box-cars. Over a hundred people were crammed into our car. The ghetto police closed the doors. When the door shut on me, I felt my whole world vanishing.

Some pretty girls were still standing in front of the cars, next to a German in a gendarme’s uniform. This man was the commander of the shaulis and the escort for our train. The girls were screaming, weeping, stretching out their hands to the German and crying, “But I’m still young, I want to work. I’m still young I want to work!”

The German just looked at them and did not say a word. The girls were loaded into the box-car and they travelled along with us. After the doors had closed on us, some of the people said, “Jews, we’re finished!” But I and some others did not want to believe that.

“It can’t be,” we argued, “they won’t kill so many people, maybe the old people and the children, but not us. We’re young they are taking us to work.”

The cars began to move, we were on our way. Where to? Perhaps we were going to work in Russia.”

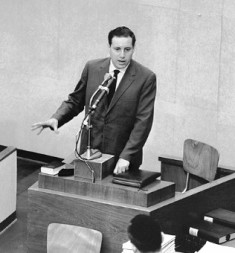

Adolf Berman Warsaw Ghetto – July 1942

“On that very day, the first victims were the Jewish children, and I shall never forget the harrowing scenes and the bloodcurdling incidents when the SS men most cruelly attacked children – children roaming in the streets; took them by force to carts, and I remember, fully, those children were defending themselves.

Even today the cries and shrieking of those children are clear in my mind. “Mama, Mama,” this is what we heard. “Save us mothers.”

Chaim A. Kaplan Warsaw Ghetto – August 1942

“The ghetto has turned into an inferno. Men have become beasts. Everyone is but a step away from deportation; people are being hunted down in the streets like animals in the forest. It is the Jewish police who are cruellest towards the condemned.

Sometimes a blockade is made of a particular house, sometimes of a whole block of houses. In every building earmarked for destruction they begin to make the rounds of the apartments and to demand documents. Whoever has neither documents that entitle him to remain in the ghetto nor money for bribes is told to make a bundle weighing 30 pounds – and on to the transport which stands near the gate.

Whenever a house is blockaded a panic arises that is beyond the imagination. Residents who have neither documents nor money hide in nooks and crannies, in the cellars and in the attics.

When there is means of passage between one courtyard and another, the fugitives begin jumping over the roofs and fences at the risk of their lives. But all these methods only delay the inevitable, and in the end the police take men, women and children.

The destitute and impoverished are the first to be deported. In an instant the truck becomes crowded. They are all alike: poverty makes them equal. Their cries and wails tear the heart out.

The children in particular, rend the heavens with their cries. The old people and the middle-aged deportees accept the judgement in silent submission and stand with their small parcels under their arms.

But there is no limit to the sorrow and tears of the young women. Sometimes one of them makes an attempt to slip out of the grasp of her captors, and then a terrible battle begins. At such times the horrible scene reaches its peak. The two sides fight, wrestle.

On one side a woman with wild hair and a torn blouse rages with the last of her strength at the Jewish thieves, trying to escape from their hands. Anger flows from her mouth and she is like a lioness ready for the kill. And on the other side are the two policemen who pull her back to her death.”

Edi Weinstein Deported from Losice to Siedlce en-route to Treblinka death camp 22 August 1942

“The procession was finally ordered to halt a short distance from Stock Lacki, several miles from the county seat, Siedlce. The SS officer allowed the carts to move on and lashed out with a riding crop at people who attempted to follow them.

He allowed my mother to pass anyway, but when I tried to follow her he struck me in the head and forced me to stay where I was. Tears poured from my eyes as I struggled to make out Mother’s retreating figure. I was glad to have taken the blow instead of her. I could not know then that my eyes were following the person dearest to me of all, Mother for the last time.

We reached Siedlce at twilight. We looked at the wagons that had carried some of the women and children. They were emptied quickly and sent on their way. The peasant carters were allowed to take the parcels and suitcases for themselves.

In the streets, Poles were grabbing anything they could pick up, so the Wagoner’s tried to leave town as fast as possible. Everything was open and shameless, as though things like this happened everyday.

We were led into the Siedlce ghetto, to the square opposite the burnt synagogue, where the Jewish cemetery had been. Everywhere we saw freshly murdered corpses. There were injured people lying about too, some of them unconscious, others screaming in pain, and others motionless but still breathing, probably no longer able to feel anything.

It was after dark when we moved on, but the shooting did not stop, since we were too closely packed to pass among the corpses easily, we could not avoid treading on them. The guards threatened to shoot us, then they ordered us to sit down.

When dawn broke the next day, Sunday August 23 1942 the German SS soldiers fired intermittently and aimlessly. In the afternoon we were finally marched off to the railroad platform. An hour later, a fire engine appeared. The mass of people, pushed toward the truck from every direction.

The fire-fighters began to spray water on the crowd. People moistened their clothing so they could remove it and squeeze out the water later. Some drank the muddy water that flowed on the platform.

On the morning of August 24 at around 10 AM a freight train pulled in and we were ordered to climb aboard.”

Mordechai Ansbacher Deported from Germany to Theresienstadt 23 September 1942

“In Theresienstadt, there were Jews from Germany, mainly old people, feeble people who had been left by themselves, without children, without family assistance; as a rule, all their relatives had left Germany, and they were left behind without help. They adjusted to the conditions at Theresienstadt with great difficulty.

There were cases of quarrelling between them and persons from other countries. They generally lived in a house, or in one room, together with people from various countries - one from Austria, one from Czechoslovakia, one from Germany, one from this town and another from some other town, one religious and another not religious. They performed their bodily functions in the room itself, for they no longer had the strength to stand on their feet. Particularly the Jews from Germany - it can be said - fell like flies. Many of them died already within the first months of arriving there. Nevertheless, it was very strange to see with what form of address, with what respect, one spoke to the other, particularly amongst those who came from Germany.

It was strange, for example, that people who were very hungry and were mostly dying from starvation, from dysentery, when they fell upon the remnants of food, upon potato peels, you heard occasionally: "Please excuse me, Herr Sanitaetsrat (Medical Councillor); Herr Staatsanwalt (Mr. State Attorney), please allow me to get to the potato peels for a little while." It was really shocking.

Generally speaking, with all these niceties of behaviour, people cared for themselves, and owing to the starvation, they did not observe the sanitary regulations according to which it was forbidden to go near the remnants, but one would push the other and help himself. What would he find? Perhaps a few peels in the dirt, and he would swallow them unwashed.

Originally I lived together with my mother in house No. L206. The Theresienstadt ghetto was divided into large buildings, barracks and blocks of houses. Each block of houses had its own specific number. There was an office called "Evidenz" (Registration). There we were given a slip of paper after we arrived with the transport from Wuerzburg, on the way from Silesia. This was the place where they took away from everyone those things that were considered forbidden, such as thermos flasks, beverages, cigarettes and toilet paper.

After we had waited a long time in the blazing sun, they transferred us on foot to house L206. We were allocated the attics, for all the rooms were already full, and said: This is where you will sleep, this is your place. I remember in our building there were people from Wuerzburg in the early days, for a week later half the people died right away - amongst those who died was Director Mandelbaum. “

Adolf Hitler Fuhrer 8 November 1942

“You will recall the session of the Reichstag when I stated: If Jewry imagines for a moment that it can engineer an international world war to annihilate the European races, the result will be not the annihilation of the European races but the annihilation of Jewry in Europe.

They always laughed at me for being a prophet. Countless numbers of those who used to laugh then are laughing no longer. Those who are still laughing now, will perhaps not be laughing much longer either. This wave will spread out across Europe and across the whole world.”

Chaim Hirszman Survivor of Belzec Death Camp, deported from Zaklikow November 1942

“We were entrained and taken to Belzec. The train entered a small forest. Then the entire crew of the train was changed. SS men from the death camp replaced the railroad employees. We were not aware of this at that time. The train entered the camp. Other SS men took us off the train. They led us altogether – women, men children – to a barrack. We were told to undress before we go to the bath. I understood immediately what that meant.

After undressing we were told to form two groups one of men and the other of women and children. An SS man, with the strike of a horse-whip, sent men to the right, or to the left, to death – to work.

I was selected to death, I didn’t know it then. Anyway, I believed that both sides meant the same – death. But, when I jumped in the indicated direction, an SS man called me and said: “Du bist ein Millitarmensch, dich konnen wir brauchen.” (You have a military bearing, we could use you.)

We, who were selected for work, were told to dress. I and some other men were appointed to take people to the kiln. I was sent with the women. The Ukrainian, Schmidt, an Ethnic German, was standing at the entrance to the gas-chamber and hitting with a knout every entering woman.

Before the door was closed, he fired a few shots from his revolver and then the door closed automatically and forty minutes later we went in and carried the bodies out to a special ramp. We shaved the hair of the bodies, which were afterwards packed into sacks and taken away by the Germans,

The children were thrown into the chamber simply on the women’s heads. In one of the ‘transports’ taken out of the gas chamber, I found the body of my wife and I had to shave her hair. The bodies were not buried on the spot, the Germans waited until more bodies were gathered. So, that day we did not bury.”

Richard Bock SS Rottenfuhrer at Auschwitz – Birkenau Witnesses to a Gassing of Jews during the winter of 1942 /43

“Holblinger said to me, “Richard, are you interested in seeing one of the actions?” I said, “Yes, very interested indeed,” and he said, “I’ll take you with me this evening.” We drove out to Birkenau, not to where the ramp was later but where the train stopped on the big slope. It was a transport from Holland and the Dutch Jews who came to Auschwitz were very elegant and rich.

He parked his ambulance there and I sat in it pre-tending to be the co-driver. Then they drove them off in a lorry to Bunker One, where there were four big halls. The halls did not have a proper roof, just a sloping top. At first Holblinger did not have anything to do. Then they went into the hall and the new arrivals had to get undressed, and then the order came, “Prepare for disinfection.”

There were enormous piles of clothing in there, and there was a board running around so that the piles did not collapse. And the new arrivals, the Dutch people, had to stand on top of this great heap of clothes to get undressed. Lots of them hid their children under the clothes and covered them up, then they shouted, “Get ready,” and they all went out, they had to run naked approximately twenty yards from the hall across to Bunker One.

There were two doors standing open and they went in there and when a certain number had gone inside they shut the doors. That happened about three times and every time Holblinger had to go out to his ambulance and they took out a sort of tin- he and one of his block-chiefs – and then he climbed up the ladder and at the top there was a round hole and he opened a little round door and held the tin there and shook it and then he shut the little door again.

Then a fearful screaming started up and approximately after about ten minutes it slowly went quiet. They opened the door – it was a prisoners’ Sonderkommando who did that – then a blue haze came out. I looked in and I saw a pyramid. They had all climbed up on top of the other and then the prisoners had to go in and tear it apart.

They were all tangled, one had his arm down by another’s foot and then round it and back up again and his fingers were sticking in someone else’s eye, so deep. They were all tangled, they had to tug and pull very hard to disentangle all these people. Then we went back to the hall and now it was the turn of the last lot to get undressed, the ones who had managed to hang back a bit all the time.

One girl with beautiful black hair, was crouching there and didn’t want to get undressed and an SS man came up and said, “I suppose you don’t want to get undressed,” and she tossed her hair back and laughed a little.

Then he went away, and came back with two prisoners and they literally tore the clothes off her then they grabbed an arm and they dragged her across to Bunker One and pushed her in there. Then the prisoners had to check where the small children had been hidden and covered up. They pulled them out and opened the doors, quickly again and threw all the children in and slammed the doors.

“I am going to be sick, “I said, “I’ve never seen anything like it in my life, its absolutely terrible.” I can’t stand it anymore and he said, “You do get used to anything in time.”

Jack Schwartz Prisoner from Slovakia at Majdanek (Lublin) Concentration Camp December 1942

“The weather was awful. Snow, ice, cold wind. The barracks, to which we were led were full of lice, nits and holding three times the number of people. There was practically no room to sleep. No one could fall asleep; the lice were eating us alive.

At dawn, in that horrible weather, we were chased outside, exhausted, stiff from cold and dampness. The smell of burning flesh irritated our noses. We shivered, standing for the morning roll call which lasted unusually long, more or less until noon.

Suddenly, we went for selection. A group of well-uniformed SS men appeared with bloodthirsty, mad dogs, holding the leashes in one hand and whips in the other. They ordered us to undress and walk by them naked in single file.

Whoever, tripped, walking in the snow, or had any wounds on their bodies, was sent directly to the gas chamber. Those who survived could put on their clothes and live longer for some time. We survived, when thousands perished.”

Hirsch Berlinski Jewish Underground Fighter Warsaw Ghetto – January 1943

“Thursday, January 20. Today I am with the Ha-Shomer people again. Mordecai showed me the arms that were taken: a rifle and a Parabellum. The weapons and equipment were stripped off the Germans, and we already knew how to use them.

Mordecai reported on the battle that took place at the corner of Zamenhofa and Niska when he stood among a group of people who had been caught and took the initiative to open fire. Some of the SS men were killed or wounded: others fled, leaving their hats and even weapons behind. Then the Germans set flame to the house in which Mordecai and his squad were holed up.”

Richard Glazar Czech Jew who escaped from Treblinka February 1943

“The “dead season” as it was called began in February 1943, after the big trainloads came in from Grodno and Bialystok. Absolute quiet, it quieted in late January, February and into March. Nothing. Not one trainload. The whole camp was empty, and suddenly, everywhere there was hunger. It kept increasing.

And one day when the famine was at its peak Oberscharfuhrer Kurt Franz appeared before us and told us: “The trains will be coming in again starting tomorrow.” We didn’t say anything. We just looked at each other, and each of us thought: “Tomorrow the hunger will end.” In that period we were actively planning the rebellion. We all wanted to survive until the rebellion.

The trainloads came from an assembly camp in Salonika. They’d brought in Jews from Bulgaria, Macedonia. These were rich people; the passenger cars bulged with possessions. Then an awful feeling gripped us, all of us, my companions as well as myself, a feeling of helplessness, of shame. For we threw themselves on their food.

A detail brought a crate full of crackers, another full of jam. They deliberately dropped the crates, falling over each other, filling their mouths with crackers and jam. The trainloads from the Balkans brought us to a terrible realisation: we were the workers in the Treblinka factory, and our lives depended on the whole manufacturing process, that is the slaughtering process at Treblinka.”

Antonius Bardach Sobibor Survivor March – October 1943

Antonius Bardach was deported from the camp of Mérignac to Drancy, where he arrived on 2 February 1943. He left six weeks later for Wlodowa-Sobibor on 25 March 1943 (convoy 53).

“For this transfer I was shut up with about 30 other prisoners in a cattle truck, this wagon was then sealed. The journey lasted six days without food or drink in the wagon, which stank of excrement because we were obliged to use it as a toilet. During this journey, a young prisoner died.

When the train reached its destination, the doors were opened and the prisoners were thrown out with violence and under blows from whips. We were driven to an open square in the camp; there they asked for 13 volunteers to remain in the camp of Sobibor, I then volunteered.

We were then stuck into a barrack. The other prisoners, men, women, children had to undress. They were all put under the “shower”; there, they were gassed, then they were burned at the crematorium. I myself was forced to help collect the victims’ personal belongings and clothes. I believed I was going mad. Fire and smoke mounted up in the crematorium. There was an acrid smell throughout the camp.

“One day, I had to bring wood intended for burning the corpses, I was supposed to bring the wood at a run, I was exhausted, I couldn’t run any more. An SS guard picked up a piece of wood and hit me on the head without stopping. There was no medical care.

“Then, I was also put in a punishment commando for two weeks, for the following reasons: I was obliged to help take corpses out of a train into which blue acid (“Blausäure”) to kill the prisoners. Some corpses were already decomposed, we were supposed to take them out and throw them into a trailer. We drove it to the chimneys of the oven. In a wagon I found a woman alive and I spoke to her, a German guard noticed this and beat me violently.

He ordered that I should be given 50 strokes of the whip. The punishment commando consisted in reducing the food, which was already limited, and in carrying all work out at a run. I had serious diarrhoea, but I hid it, because all the sick were at once led to the gas chambers and then burned. I always suffered from moral ill treatment.

Sobibor was a camp of destruction. The trains full of victims came mainly from France and the camp of Vught. In October 1943 I managed to escape, and I stayed in the forests around Lublin until the Liberation.”

Chaim Frimmer Jewish Underground Fighter April 1943

“At five in the morning a loud rumble was heard. Suddenly I saw from my lookout on the balcony that cars had come through the ghetto gate. They reached the square, stopped, and soldiers got out and stood to the side.

Then a truck arrived carrying tables and benches. The distance between me and the cars was about 200 metres, and since I had good binoculars I could see them clearly. The tables were set up in a D-shape, wires were laid and telephones were placed on them.

Other cars came with soldiers bearing machine guns. Then motorcycle riders arrived and some ambulances and light tanks could be seen stopping by the entrance. The Latvians who had been standing there through the night were removed and sent en-masse in the direction of the Umschlagplatz.

At six a column of infantry entered, one section of the column turned into Wolynska Street and the other remained in place, as if awaiting orders. Before long the Jewish Police came through the gate. They were lined up on both sides of the street and, as ordered, began to advance toward us.

I would report everything to a fighter lying down not far from me –who in turn passed word on – to the command room, where Mordecai Anielewicz, Yisrael Kanal and others were seated.

When the Jewish Police reached our building, I asked how to proceed: Attack or not? The reply was to wait; Germans would surely follow, and the privilege of taking our fire belongs to them. And that’s exactly what happened: After the Jewish Police crossed the street an armed, mobile German column began to move. (I was ordered to wait) until the middle of the column had reached the balcony and then throw a grenade at it, which would serve as a signal to start the action.

A mighty blast within the column was the signal to act. Immediately thereafter grenades were thrown at the Germans from all sides, from all positions on both sides of the street. Above the tumult of explosions and firing we could hear the sputter of the German Schmeisser (a sub-machine gun used by the German army) operated by one of our men in the neighbouring squad. I myself remained on the balcony and spewed forth fire from my Mauser onto the shocked and confused Germans.

The battle lasted for about half an hour. The Germans retreated leaving many dead and wounded in the street. Again my eyes were peeled on the street and then two tanks came in, followed by an infantry column. When the tank came up to our building, some Molotov cocktails and bombs put together from thick lead pipes were thrown at it.

The big tank began to burn and, engulfed in flames made its way toward the Umschlagplatz. The second tank remained in place as fire consumed it from every side.”

Juergen Stroop SS and Police Leader Warsaw District

25 April 1943

“Today’s operation ended for almost all assault units with gigantic fires, which induced the Jews to leave their hiding places and refuges. A total of 1,690 Jews were apprehended alive. According to Jewish accounts, these definitely included parachutists who had been dropped and bandits who had been supplied with weapons from an unknown source.

A total of 274 Jews was shot. As on previous days, uncounted Jews were buried under the rubble of demolished bunkers and burned to death, as we discover all the time. In my opinion, today’s booty of Jews encompassed a very large part of the bandits and the lowest elements of the Ghetto.

Because darkness set in, we did not proceed with immediate liquidation. I will try and obtain a train for Tll tomorrow. Otherwise, the liquidation will be carried out tomorrow.

There was armed resistance again today. In one bunker, 3 pistols and explosives were captured. Further, considerable amounts of paper money, foreign currency, gold coins and jewellery were secured today. The Jews still have considerable wealth at their disposal.

During last night, a glare of fires hovered over the former Ghetto; this evening one can see a gigantic sea of flames. Since large numbers of Jews continue to be discovered during each systematic and regular sweep, the operation will be continued on 26 April 1943, starting at 10.00 hours. As of today, a total of 27,464 Jews of the former Warsaw Jewish Ghetto has been apprehended.”

Note: Tll was the Nazi designation for the death camp at Treblinka, TI was the designation for the nearby forced labour camp which was located approximately 2km from the death camp.

Heinrich Gley German Member of staff at the Poniatowa Labour Camp, Lublin district 3 November 1943

“In November 1943 – I don’t remember the exact date – one night I was called to Gottlieb Hering – the commander of Poniatowa. When I entered Hering’s room, there were two police officers with him…

The officers informed Hering that the whole camp was surrounded by a police unit. The police unit was under orders to liquidate all the Jews in the camp, without any exception. During the conversation, the officers expressed the opinion that the liquidation of the Jews was inevitable because otherwise security could not be guaranteed. Whether the assumption about the endangered security situation was based on the report of the successful uprising in Sobibor, I don’t know…..

In the meantime all the Jews were ordered to concentrate in some specified places. They were separated in such a way that the Jews from the main camp were in the large hall and the Jews from the “settlement” were to line up at a square.

From my room I could see how the Jews, entirely nude, were taken from the hall to the trench. The trench was zigzag. It was about 300 – 500 metres distant from the main hall. A tight chain of armed policemen guarded the way. I could not see the shootings, but I heard the shootings.

After the action was finished, I saw the corpses. In the evening, after completing the action, the police unit left. According to my estimation, the strength of the police unit was between 1,000 – 1,500 men.”

Filip Muller Jewish member of the Auschwitz – Birkenau Sonderkommando 8 March 1944

“That night I was in Crematorium II. As soon as the people got out the vans, they were blinded by floodlights and forced through a corridor to the stairs leading to the “undressing room.”

They were blinded, made to run. Blows were rained on them. Those who didn’t run fast enough were beaten to death by the SS. The violence used against them was extraordinary. And sudden, not a word………..

As soon as they left the vans, the beatings began. When they entered the “undressing room” I was standing near the rear door, and from there I witnessed the frightful scene. The people were bloodied. They knew then where they were. They stared at the pillars of the so-called International Information Centre I’ve mentioned, and that terrified them. What they read didn’t re-assure them.

On the contrary, it panicked them. They knew the score. They’d learned at Camp B2B what went on there. They were in despair. Children clung to each other. Their mothers, their parents, the old people, all cried, overcome with misery.

Suddenly some SS officers appeared on the steps, including the camp commandant Schwarzhuber. He’d given them his word as an SS officer that they’d be transferred to Heidebreck. So they all began to cry out to beg, shouting “Heidebreck was a trick! We were lied to! We want to work! We want to live!”

They looked their SS executioners in the eye, but the SS men remained impassive, just staring at them. There was a movement in the crowd. They probably wanted to rush to the SS men and tell them how they’d been lied to, but then some guards surged forward, wielding clubs, and more people were injured.

The violence climaxed when they tried to force the people to undress. A few obeyed, only a handful. Most of them refused to follow the order. Suddenly, like a chorus, they all began to sing. The whole “undressing room” rang with the Czech national anthem, and the Hatikvah. That moved me terribly, that…………. That was happening to my countrymen, and I realised that my life had become meaningless. Why go on living? For what? So I went into the gas chamber with them, resolved to die. With them.

Suddenly, some who recognised me came up to me. For my locksmith friends and I had sometimes gone into the family camp. A small group of women approached. They looked at me and said, right there in the gas chamber.

One of them said: “So you want to die. But that’s senseless. Your death won’t give us back our lives. That’s no way. You must get out of here alive, you must bear witness to our suffering, and to the injustice done to us.”

Hugo Gryn 14 Year old Jewish boy describes his arrival in Auschwitz Birkenau May 1944

“We were exhausted, thoroughly demoralised and frightened and the train stood for some time. We could only hear the shunting of engines, crunch of people walking outside, and eventually, well into daylight, the door pulled open and people now being herded out, and an amazing scene.

It reminded me of what I imagined a lunatic asylum would be like, because in addition to the SS who were moving up and down and pushing people around towards the head of the platform, the other people there wore this striped uniform, with a very curious –shaped hat, and they were just moving up and down taking so-called luggage out of the train.

One of them I would say saved my life, because he went around muttering in Yiddish , “You’re eighteen, you have a trade,” which I took to be the mutterings of a lunatic because it was such a curious thing to say – that’s all he kept saying to people – particularly to young people.

My father was there and took it seriously, and by the time we in fact came to the head of this platform where the selection was taking place I had already been rehearsed, so that when the SS man says, ”How old are you?” I said I was nineteen; and “Do you have a trade?” “Yes, I am a carpenter and a joiner.”

My brother who was there was younger, he couldn’t say he was nineteen, and so he was sent with the old people the wrong way and my mother went after him. The SS man quite crudely and violently pulled my mother back.

She said, “Well, I want to be with my little boy, he’s frightened.” “Don’t worry he said, “You will meet him later.” Well, that of course was in fact the last time I saw my brother.”

Jakub Poznanski Lodz Ghetto 2 September 1944

“There are horrible rumours, namely that all the transports supposedly going to Vienna or to inside the Third Reich are actually going to a horrible camp in Auschwitz. Even the once-omnipotent Rumkowski was sent out with one of the latest transports. In a severe heat wave he was placed in a closed car, with more than eighty other people. That’s how Hans Biebow fixed him up.”

Szymon Srebnik Chelmno Death Camp January 1945

“The camp was liquidated and the barracks dismantled. Machines for shredding clothes and underwear were sent back. The furnaces were also dismantled.

In the granary there were still 87 Jewish workers. Those were tailors and shoemakers. They lived upstairs. The number of workers decreased and finally there were 47 of them left - 22 tailors and 25 courtyard workers.

Bothmann wanted to kill me several times, but Hafele liked me and this partly helped save my life. While the clothes were being sorted, high ranking SS-men and chose something for themselves. The chosen items were packed and carried to their apartments.

When the Soviet Army was advancing quickly, one night we were ordered to leave the granary in groups of five. I cannot remember the date. The area was lit with car headlights. I went outside in the first group of five. Lenz ordered us to lie down on the ground.

He shot everybody in the back of the head. I lost consciousness and regained it when there was no one around. All the SS men were shooting inside the granary. I crawled to the car lighting the spot and broke both headlights. Under the cover of darkness I managed to run away.”

Menachem Weinryb Auschwitz Death March survivor 13 April 1945

“One night we stopped near the town of Gardelegen. We lay down in a field and several Germans went to consult about what they should do. They returned with a lot of young people from the Hitler Youth and with members of the police force from the town.

They chased us all into a large barn. Since we were five to six thousand people, the wall of the barn collapsed from the pressure of the mass of people, and many of us fled. The Germans poured out petrol and set the barn on fire. Several thousand people were burned alive.

Those of us who had managed to escape lay down in the nearby wood and heard the heart- rending screams of the victims. This was on April 13.”

Wynford Vaughan-Thomas BBC Radio Journalist Belsen May 1945

“A pile of women’s bodies, an enormous pile, you have probably seen the photographs, but the smell and the horror it. There were little children playing touch around the pile of these bodies and that was the final, horrible end.

In the huts typhoid, everything, had broken out and you couldn’t hear yourself speak for the death rattle. There were people lying on top of each other, sick, vomiting, withered bodies crawling on their hands and knees.

I went into one area where they had to seal it off because of typhus; through the wire came what I thought were broken twigs, they were the arms of people and the voice, the croaking sound of voices that had withered at the roots, and I’ll never forget it.

Sometimes you wake up at night and you hear sounds and you think you’re in Belsen again, that horrible, awful sick smell and the final indignity of taking the human body and bulldozing it as if it was worth nothing.

You were surrounded by this neutral pine forest and I can’t look at Xmas trees sometimes without remembering Belsen behind it. It was sealed off in this dark north German plain and you felt you’d reached the cesspit of the human mind.”

Sources: The World at War by Richard Holmes, published by Ebury Press 2007 The Holocaust by Sir Martin Gilbert, published by Collins London 1986 The World at War – Television Documentary - Genocide 1973 Those were the Days, Klee, Dressen, Riess, published by Hamish Hamilton London 1991 The Death Camp Treblinka, edited by Alexander Donat, published by Holocaust Library New York 1979 17 Days in Treblinka, by Eddie Weinstein, published by Yad Vashem publications Jerusalem 2008 The Stroop Report, published by Secker & Warburg London 1979 Lodz Ghetto – Inside a Community under Siege, compiled by Alan Adelson and Robert Lapides, published by Viking 1989 The Jews of Warsaw 1939 -1943 by Yisrael Gutman, published by the Harvester Press1982 Shoah by Claude Lanzmann, published by Pantheon Books New York 1985 The Yellow Star by Gerhard Schoenberner, published by Corgi Books 1978 Eyewitness Auschwitz by Filip Muller, published by Routledge & Kegan Paul 1979 Extermination of Jews at the Majdanek Concentration Camp by Tomasz Kranz, published by Panstwowe Muzeum na Majdanka Lublin 2007 Nizkor Eichmann Trial Transcripts Holocaust Historical Society

Copyright Chris Webb 2009 H.E.A.R.T

|

%20poses%20with%20the%20daughters%20of%20the%20town%20baker%20while%20in%20hiding%20in%20Zaklikow.jpg)