Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Esther Raab Sobibor Death Camp Survivor Selected Extracts from USHMM Interview Interview held on the 18 February 1992 (Photo's added to enhance the text)

Can you describe for me the transport to Sobibor and your arrival there, and what is was like and what happened? I didn’t come by train, I came by horse and wagon because I came from a small working camp. We were like 800 young girls and men and we rode the whole day to Sobibor and the month it was December 1942, December 22 1943, 42, I’m sorry.

And after riding the whole day in the mud and the wagons got stuck in the mud and we had to go down and pull them out, and on the way the farmers were outside, and they said there’s no way your going, they’re going to kill you and they’re going to burn you.

As much as we knew before and as much we heard, we didn’t believe. It was very hard to comprehend, to believe. Why take innocent people and just kill them with no reason at all, and as the day came to an end, was only 20km’s but it took a whole day.

Everybody of us, from us, was so disgusted that we wanted to get it over with. If that’s what they’re going to do to us, let’s do it fast, so we, wont have to suffer.

I mean not physically, we didn’t but mentally. You know it was very hard to sit there and think I have 4 hours or 3 and a half hours or 3 hours. And as we came close to Sobibor, the whole day naturally without food, without water, but that really didn’t bother, we were used to it.

The the SS came out with dogs and started barking, I mean they never talked they barked. You could never make out what they are saying. Although I spoke very well in German, I had it in school and I picked it up more experience during the time, and they started barking.

The SS told us to assemble on the platform, the railroad platform, and we all assembled there and I stood in every way, that and, and you felt already the smell there from the burning bodies and you saw the fire, but you, you didn’t believe it.

It’s just I couldn’t believe it. I myself and so my friends and all of the sudden I saw that girlfriend of mine, with whom I came walks by with a commandant from camp, that was Wagner, the biggest murderer, and the biggest of all the Nazis that ever existed.

He was caught later in 1979 in Brazil. And he picked, she picks up one girl and I said “Mira who you looking for?” and she says, “I looking for girls who know how to knit” and I said,

“That’s about my talent” and that was just a split second and she pointed out to me, he said “Raus” and I came out from the whole transport, they took out 8 girls and 2 men which were fathers of the girl – of some of the girls, one was a shoemaker and one was a tailor, and they marched us out to the camp, and we figured we didn’t have no idea what’s going on, what they are going to do later with us.

And the others marched out and at that moment I don’t you’re capable of think. You don’t plan, you don’t think, you don’t argue, you don’t ….. you just numb, and that’s how I was, numb.

And then he took us, all the girls with the 2 men, and they marched us into the camp and as we saw the camp was very small, very small because when we came in we made out, up 20 women and 100 men, so was very small and that smell.

I thought to myself “What’s that smell?” The smell was….. you couldn’t take it anymore. And as he puts us in, in an empty barrack and then came like the commandant, the Jewish commandant of the inmates, he said,

“You know where, where you are?” and we didn’t say boo because you didn’t know who to trust, you didn’t know what to say, so we had to be very careful, and by looking at each other we understood what we are supposed to do, and he explained it right away.

“You see the fire, you see this,” and then they brought us in blankets and bread and coffee and we figured that’s the last meal, and we remained there until the morning, we laid down we slept, we didn’t sleep, but I cannot explain the feelings we had.

If to believe that all those who were with us are not here anymore… or, or not to, we, we didn’t know we were just numb to the whole situation.

Early in the morning, they told us to get up, and they marched us off to the sorting shed, the next morning, where they told us to sort out the belongings of the people, then when we found the belongings and the pictures and the documents of the girls and the young men that were with us, we realised, but it’s very hard to just put it into your head they’re all dead.

Why?

It was very difficult, it was very difficult, it was very hard, and inside it builds up right away such a resentment, such a feeling of revenge, such anger, if I could just kill one.

For that what had happened, I would feel better, but you have to keep your mouth shut, and just pretend you don’t see, you don’t hear, no emotions, no emotions whatsoever, we didn’t even cry not one of us.

Can you describe the transports coming in?

The transports, well, usually most of them used to come in during the night, but there were some in the daytime too. When you heard that whistle from the commandant of the camp, that man, that the transport was coming in, and the men in the camp should get ready to unload the people and so that whistle was like somebody would tear out your insides, you knew here are other people, children, our elder people, people who never did anything wrong in their life, and they’re going to go, and you cannot say, you cannot resist, you cannot.

Inside it built up that revenge and that resentment and that anger, and that pain, sometimes they came in during the day and sometimes so many came that they couldn’t handle, so they would put them behind our …… and we were ….. and tell us just to walk back and forth, and forth and back, so what they told them that they are going to work should seem to them to be the truth and that was hard, it was hard.

You walk by and you look at the face and you know in half an hour wont be here, can’t even tell. You just put on a smile, your best face you can, it hurt, it was very hard.

And then some transports usually, when I had to work near the railroad tracks, you know near the ….. there was and, and sometimes when a transport came, we had they sent us all to the compound, except for those who worked with the unloading of the people, but a few times we went to clean the houses of the SS, and there wasn’t enough time to run back, so they would lock us in, or we knew ourselves we are not supposed to walk out and watch it, and sometimes we saw the people the way they were delivered, before they’re dead, they torture before they’re dead.

We saw them leaving and screaming and children crying and elderly people and I cannot explain the feeling that I had, and I wondered why, why, just why that why was such a big question and nobody could answer. Like for instance once I was called to clean up the….. this is uh, an incident which is going to be with me the rest of my life.

All the people that I saw going, and, and imagining what’s going to happen, but once a big shot was supposed to come to Sobibor, usually they brought them, even Himmler was in Sobibor to show them how efficient and how perfect they had killing, and how good, and they brought a transport so they took me to clean up the quarters, the living quarters of the SS, of some of the SS people which the windows face the railroad track.

And when I was there cleaning with another girl, the whistle was there that a train comes and so we knew we have to remain there, we cannot go out, and the transport came in and went everything very fast, the load, unloading of the people, and a mother left a baby, I don’t know for what for what reason, in the boxcar and Frenzel who was at that time in charge of the transport, grabbed that little baby and smashed the head, the skull against the boxcar, and they just threw it in like a dead rat and that’s just I cannot forget.

I was at this trial for, about 4 times and I told them what he did, he didn’t deny it, but he followed orders and this I cannot forget. Why kill that child in such a miserable way? Why? Why?

It was a human being. I just wish that somebody would do to his children and he should have to watch. And this is with me, I cannot for all the gruesome things that I saw, I saw a transport come, the people probably resisted in the boxcar, I don’t know, so they threw in chlorine into the boxcar, and the whole transport came, so dead, natural.

All bodies were 3, 4 times the size, some even were busted open, and they just deposited them. It’s, it’s really difficult to think about it and to talk about it. And all these just built up in me, such an anger, and the feeling of revenge and I remember I came to the camp with a pair of brown leather boots which, not everybody had, probably nobody, and I said to the group that we slept together, I took my boots, wrapped them up nicely, and put them under the bunk-bed, under my head, but they said,

“Why you put them?” I said “With these boots I’m going to escape from Sobibor.” Don’t ask me why. Don’t ask me how. And maybe it doesn’t even make sense, but I’m going to escape with these boots, and I did escape with these boots.

And things like this, every day was something new. Like they took all the sick people, when we stood in the sorting shed and sorted the things from the people, the belongings, you see the wagons go by, and the older people, or children who were maybe orphans or, were thrown in like cabbages and then at the end rides Gomerski, who was in charge of them with a pistol and just asks,

“Who is tired and who cannot work, and who is sick?” “I am going to help you.” And then bullet and then a bullet and I cannot describe here the feeling. I cannot describe. I don’t think there are words really to describe it. I was at his trial too. He said also he followed orders. And I told the judges,

”If Hitler would come now and give him orders, or somebody else, they would do it again.” And it was very hard just to watch, like winter sometimes came a transport and they were busy and they couldn’t handle so many. \

They told the people to undress, in the snow, in Poland it’s very cold in the snow, naked, and they chased them like, like cattle, cattle I think you take better care of, all the way straight to the gas chambers.

Can you talk about uh you talked once about a person named Michel and the charade that he had telling people to hang their clothes and what he talked about?

This was in the beginning when it first started. They, they weren’t as well organised as later on, so the German efficiency, they had a yard, a fenced in yard with hooks to hang up their clothes and they would assemble all the people from the transport and he would go out – Michel, we used to call him the “House Beater” – you know he would say in German,

“Jews you think you’re going to die. It won’t happen. It won’t happen to you. You’re brought here, you give up all your belongings with a number, you’ll get a number and you hang up your clothes, and you go to the showers, because we are afraid of sickness, and then you’ll be sent to work.

The way it was done, with such German efficiency and everything to the minute and to the second and, and you always ask why, why, you cannot ask it.

It wasn’t easy to be in Sobibor or any other camp, I suppose, death camp. I don’t think you could even think straight. I remember once came a big, when Himmler came to our camp, they brought 400 girls from Majdanek, that was also a death camp, to show him, and that’s when they uh, ordered to shave the heads, from those….. and they shaved the hair from them, and he went out and, and ……….., and they got such reward, that they doing such a good job, that after a while they liquidated Treblinka.

All of a sudden when they closed up Treblinka they brought all the inmates to Sobibor to be killed, they were afraid to do that there. So one afternoon all of a sudden, the whistle, and they lock us in our camp, then we knew something extraordinary has happened.

And we could hear the train coming in, the Ukrainians took care of it, not our inmates and we could hear shots, and we counted the shots, so much and so much, and after the last shot, they came they let us out and they sent us to sort out the belongings, and as we started we all….. very careful, everything for papers, for documents, for notes, for anything and we saw that they were from Treblinka, and every, and every pocket was almost a note, “Take Revenge.

Take Revenge. We couldn’t, maybe you can take the revenge.” And in times like this, and you felt they using you and look at what they do to you, the same thing, so why be here? Why? Just for their convenience? Why? And after a while, they brought the people from Belzec, because they closed up Belzec too at that time, and they were in the same story, happened there.

And then they expanded Sobibor and business started booming. Night and day you had transports. You, we used to work 14, 16, 18 hours a day, I mean into the night, just the men took care of the helping to unload, the people, empty the belongings and then you had to sort and they had to ship it to Germany.

It was very difficult, I cannot explain that feeling, and the resentment and the hate and the revenge. The revenge was so great the…………..

Can you talk about the choices that the guards had versus the choices that you prisoners had?

First of all the guards had all the privileges. They could do whatever they wanted. They didn’t have to account if they killed somebody or hit somebody, or mistreated somebody.

We didn’t have no privileges. We were there to serve the Germans, probably as long as they would have needed us, and then it would be the end. The guards could go outside, the guards could have furlough, the guards had enough food. It’s altogether a different ballgame.

Did you have choices?

No I didn’t have no choices. Whatever, I was told I had to do, and maybe better than I could and whatever they gave me to eat, and that’s it. The only thing we had in our favour in Sobibor, which other camps didn’t have, I don’t know about Treblinka and Belzec that they didn’t shave our hair, the inmates, and that we could take clean clothes from the transports, and change and we could wash ourselves.

And I think this was keeping ourselves clean wasn’t so dehumanising that people had in other camps with the dirt and filth. They did it only for one reason. First of all was as a propaganda, if some transports came in, they should see we still look like human beings, and second of all they lived so close to our quarters, the German quarters, that they were afraid for diseases.

And there was enough clothes so we could take and keep ourselves clean. This was one of the biggest things that kept us going. We were hungry. Not enough, sometimes we stole something from the transport, the people used to bring bread or, whatever, but there that was very risky, because most of the time when we walked to the barracks from the working place, they used to check us.

They used to check us if we didn’t take something or so, but we tried, sometimes we were successful, but the main thing that we could keep ourselves clean, and that’s why we had the courage and that will to do something, because when you way down physically, and filthy and dirty and shaven and this, you give up very fast, but I feel that kept us going.

And that’s why we thought even if one makes it and go out, he’ll look normal, he wont be right away suspicious. He has a striped outfit, he doesn’t have no hair, that was one plus that they didn’t think about that we had in our favour to think about uprising and about taking revenge and so forth.

Once a partisan group approached the camp and they wanted, I don’t know, liberate, or whatever they wanted to do, but we knew it was a partisan group and during the night a whistle came, we had all to run out, whatever we had on, and stay barefooted in the snow, probably 2,3 hours or more, surrounded by machine guns and everything.

They figured if they should happen to go through, they’ll kill us all, but they left the Partisans and we went back, and at that time, they made mine fields around the camp, before there were no mine fields.

We were so deep in the woods, that nobody could even know that something goes on. So we started thinking about uprising and about revenge, and I think that kept us going, although it was silly thought, but you know that gave us the courage to survive, to do, because we planned, we planned.

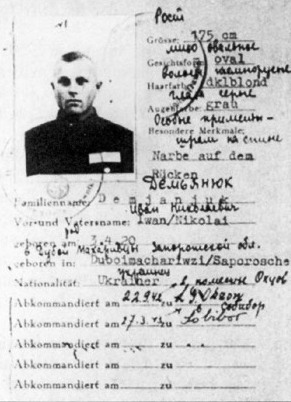

The plans weren’t worth it, maybe in the beginning, five cents, but we planned and we saw ourselves outside, and we saw all the Nazis killed and this kept us going every day. In 1943 probably in February or well, Leon Feldhendler was picked out from a transport and brought in. We were cousins by marriage and after we told him what’s going on, everybody who came in or they took him out, if they killed ten from us, they picked out another ten from the next transport.

We told them and he said, “We have to escape.” and we asked “How?” he said “There must be a way and we’re gonna escape.” And we tried started planning and going to meetings, which only a few went because you had to be very careful, and coming back you felt like you doing something, you planning something, you trying something.

If you succeed it would be wonderful, if not you’ll get a bullet in the back – it’s better than going to the gas chambers. I promised myself I’ll never go to the gas chamber, I’ll start running. I’ll start do – they have to waste a bullet.

And we started organising and talking and it kept us alive again, you know that maybe we’ll be able to take revenge for all those who can’t, who already burned there. And, and we promised ourselves it didn’t matter if we survive or not, but to do something, not the, the world shouldn’t say “the Jews went like sheep to the slaughter.”

It’s not true. We saw a lot of incidents in camp where women hit the SS people. They hit once the Untersturmfuhrer Niemann, they almost popped out the knife for him, he was all bandaged up. They did, they did but they’re not here to tell the story.

And I feel that the resistance, in general, not talking about Sobibor, which Sobibor had a successful revolt. The others tried and didn’t succeed you know. This was the only successful revolt. But people fought back. They fought back in the woods, they fought back on the train stations, they fought back every step of the way, but they, they are not here to tell.

And that hurts, it hurts. And, and the uh, and time runs out on the survivors too.

Tell me what a death camp is? Assume that I don’t know. Just define a death camp as opposed to other kinds of camps.

You see our ca- the other camps were half slave labour camp, and half death camp. There were no such thing as slave labour camp. That was only strictly the inmates that were picked out from the trains – they just took care of the killing of the people.

I mean they didn’t kill them, but they helped you know they had to. And of the work in the camp of taking care of the SS people, that’s the difference. From Sobibor to Auschwitz let’s say, Auschwitz was a half slave labour camp and a death camp. Sobibor was just a death camp. No slave labour there, no work, no producing, no nothing doing.

Can you tell me about the seamstress and her baby? She was there, she came with a transport in my time already, with her husband. She was a seamstress and he was a tailor, but during the film she says that he was in the Partisan group, but she came with her husband and she had that baby about 2 weeks and then they finally found it, because they used to come in unannounced.

Unannounced?

Unannounced and they walked in and saw the baby. They gave her a choice, it’s true. They gave her a choice that they’re going to take the baby and she can remain because she was very good seamstress.

They used to wear underwear only from silk, from the parachutes. They didn’t use plain materials, the SS. So and she was excellent making shirts and underwear from those parachutes.

We have to reload. Okay start again and do that whole thing again

With the…..

Seamstress, tell me about what her work was, what she did, what did they ..

She came into the camp with her husband, he was a good tailor, and she was an excellent seamstress and the Nazis didn’t wear underwear just from plain material, everything had to be made from silk, the shirts, the underwear, so she was excellent. They brought a lot of silk from the parachutes and she used to be able, if you told her out of this piece has to come out 3 shirts and 3 underwear – it came out. I don’t know how she did it, but it came out.

And after she had a baby and we all pitched in to help. I mean first of all was the baby. Second of all, again, to do something against the Nazis, you know maybe we’ll be able. It was a challenge at the same time.

And so she kept it for two weeks. And once Wagner walked in unannounced, unexpected and he heard the baby and he gave her a choice, he gave her a choice just because they needed her, otherwise they wouldn’t have.

And which mother would give up her baby. And she just spit in his face right then and there and they shot them both. But they were such murderers that he had to shoot the baby first, so the mother should, should die with more pain, and so I mean , I cannot explain what went on in the mind of those people, of those SS people. I mean a human being was nothing as we know, but they took such a joy in seeing blood and hurting. They weren’t people, they were animals, hound dogs.

I always said they bark like dogs, and they act like wild dogs. It’s, it’s very difficult and we were very hurt at that time, when you see things like that, and especially when they took one of us.

We were a small group and you felt like they tear out a piece of you. That here she was, and here and the baby was here, and you know there was a little life, and the, uh, seamstress too and they tore it out completely and you just have to put up a face, but inside everything is boiling and boiling and boiling and it was very hard.

Not once we said to ourselves we wish they would finish up. But then one encouraged the other, especially when Leon came. You’ll see, we’ll get out and we’ll get out and one looked at the other, and figured the other one is crazy, you know, thinking even about it.

And that’s how, every day passed by with the hope of revenge.

Tell me about escapes and punishments for escapes that went on.

First there escaped two people, they were…. they were plasterers, like and, at that time, there were no uh, there were no mines around the camp. So they dug a hole underneath the first fence and they escaped.

When they escaped they always explained why they’re doing things to us, they assembled us, and they said every tenth and they took out every tenth and they shot them in front of us, and if somebody escapes that’s what’s going to happen, and those two marauders didn’t make it, they didn’t make it.

Then we had, they used to take out people to the woods because they, as Sobibor was announced the best, the most efficient death camp, so they had to expand and they had to build and they had to always keep busy.

The Nazis didn’t want to go to the Russian front, so they built and they expand, and they said they need this and they took out more people in order to escape from the Russian front.

And they took out some people to the woods to cut woods and they used to make their own logs, everything was done on the premises, and two escapes. They lived a while and they are not alive anymore. They went with the guards for water and they hid and escaped.

They survived the war even. And when they escaped that day, I was in the weaponry. They were low on ammunition, so they brought some bullets which they got from the Russians and they were rusty, so a few girls, we sat there and we sanded them down, and filled the barrels with the ammunition and all of a sudden the guy who watched us, the wachmann, he was a Ukrainian, but he was a nice guy, but we didn’t trust him.

He said to us, “You’ll see what I’m going to do, one will get killed because of me.” And it was true, but you don’t know who to trust. And he came running in and said, “I have to lock you up, something is going on and there’s not enough time for you to go back to your compound, and we saw those people walking in from the main gate, underneath with their hands like this.

They were beaten up, you couldn’t tell their faces anymore. And then, all of the sudden, as they walked out by the veterinary, we heard the whistle, and he came in here, opened the door, and we had to run to the compound.

And, assembling right away, and as we assembled uh….. was such a dog, such a miserable character, I went to his trial too. He followed orders too. And they marched us off to Camp 3. Camp 3 was where the gas chambers, and they told us to assemble in a half moon, and all those poor guys were standing there. You couldn’t tell who was who. That’s how they were beaten up.

And they told them to pick out another 25 from us. And they were going to be shot with them. First they held a long speech that some guys of ours killed two, uh, one wachmann, one Ukrainian, and for this we have to pay.

On the way to Camp 3 they told us that we’re all going to be shot. But as we came there, they probably changed their mind, or I don’t know why, and they told them to pick out.

And I can imagine how hard it was on those guys to go over and choose that you have to be killed. I mean, in the morning he was my friend and now I have to, it was a difficult time. The – if not, they said they’re going to take 50.

So some stepped out, and they picked blindly and they shot them all in front of us, in their faces. They wouldn’t have let them and Frenzel went over, whoever he may be, uh, botched or something, another bullet.

And these things were so hard on us, harder than a transport, because here we’re like a family, we planned together, we suffer together, we do together and we hoped together. And if you take out such a part from us, it’s like tearing out your own heart It was the hardest but you had to go away and pretend again, that you didn’t see it. Or maybe what happened happened, it wasn’t easy, it wasn’t easy.

I always said to myself if they would kill me, it would be easier for me than to watch somebody that I knew and maybe, and ate together and stayed together and suffered together, and planned, it was very difficult, was very difficult.

Were almost, we only have one minute left, why don’t you just describe for me Wagner or Frenzel

I think Wagner, he was caught in 1979 in Brazil. Wagner was illiterate, that’s what they said. But he was such s devoted Nazi. And there were days when he needed blood. Like a dog, like uh, needs blood. He needed it. When he used to walk in with his thumbs in his pocket, we need that somebody’s going to go. Otherwise he wont ask.

Besides what he did with the transport, and we knew also. But at the same time as illiterate he was, he was so shrewd, that he knew what you think, not what you saying.

Please tell me about the Uprising?

We planned all the time, and we talked about it, and we had the plan ready. It was just a matter of time, because we had to plan when Wagner is on vacation. Because we knew on furlough, if he’ll be in the camp he’ll smell it, there’s no two ways about it. So we waited. In the meanwhile we knew their schedule with furloughs.

By being there, we knew about everything. So and before Wagner had to go 28 days before, they brought in a Russian unit from POW’s. At first we did – couldn’t understand why, but then we found out they were all Jews.

They were POW’s and we got in touch with one of the leaders – every group had a leader and we told them our plans, and we asked them because, if we didn’t know what’s going on outside, how far the front is and what’s going on in general, and he told us approximately what’s going on, and how far, and he, we needed that encouragement, and they gave us.

And I said, “Your plan is good and it’s going to work, and it has to work, and we have to try, we don’t have … what to lose.”

And we decided the date when Wagner left and the, the date was original the 13 of October and that day we all got ready, put on two sweater, and my boots I put on for the first time again and I got dressed with a coat and a kerchief and you know you didn’t take no luggage with you, you didn’t know where you were going, or if you’ll make it.

And then some units from military Gestapo came to the camp, never used to come on that day and we thought somebody maybe slipped out, but they left, and the next day exactly the plan was, at 4 o’clock should start, everybody has to kill his SS man, and his guard at his place of work.

And it started working and I was like messenger girl, going here, oh I killed them, five. I killed just throwing signals, not talking, but we couldn’t find Frenzel and we thought although the electric wire was cut, the telephone wire was cut, we were afraid that somehow he got out on the outside and, and went for help.

And this was before decided in case anything goes wrong, everybody on his own. And whoever, wherever one can run, or wherever one can jump, should go. Maybe one will survive and will be able to tell the world. And we assembled like on a normal day and then Sasha and Leon, the organisers went up on the table and they said,

“We can’t find Frenzel. Something – everybody on his own.” But a lot of people were panicky right away. A lot of people didn’t want to go, they gave up. And those who felt they want to try, just run in all directions. I saw that somebody put a step-ladder behind the carpenter’s shed and that people climbing up, no one explained that this was all split second.

And I just jumped up that step-ladder, and as I was on top I noticed a lot of bodies already on the mines, some people went before me. I got a bullet shot from the tower right here, and I fell down.

As I fell down I was so much aware that the will to live was so great, there’s no measurement to it, that I started hopping on dead bodies and soon as reached the woods, we were in the woods, it, it was I felt I did it, I made it.

For all those I just looked back to the fire, the fire was still burning, and to the people in the back and I figured I did it for you. We took revenge. What’s going to happen from now on, it’s a different story because the war was still on. And I had to survive another 9 months.

When you said everyone had to kill an SS man, what was the plan for that, how did you ………….?

If he came in, let’s say they called him in, they said his suit is ready to try on, his uniform, so when he came in he put it on, we had everybody, everybody had sand in his pockets, and a knife, this we all had, because we felt if you throw sand in the face, then its easy to stick in the knife, because the person get’s blinded. So that’s what they did.

The minute he came in, they threw sand, they stuck a knife in, and they hit him, hit him. And that’s how we did it. We didn’t have no weapons. The original plan was to assemble, to go to the weaponry, take out all the weapons and march out through the main gate.

But we didn’t succeed, the plan didn’t succeed, the plan didn’t succeed because we couldn’t find Frenzel and had to be everybody on his own, so we did the best we could with whatever we had.

Notes:

The original transcript has not been checked for accuracy nor spelling by USHMM.

There are a number of spelling mistakes in the transcript, mainly the names of the German staff which have been amended for the sake of accuracy:

Sources: USHMM

Copyright 2008 H.E.A.R.T

|