Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| ||||||

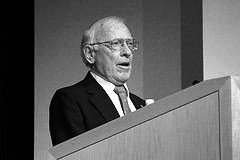

The survival of Jerry Koenig Hiding in Kosow- Lacki

The situation in the Warsaw ghetto was truly horrendous – food, water and sanitary conditions were non-existent. You couldn’t wash, people were hungry and very susceptible to disease because of their weakened condition. It is amazing what happens to people when they’re deprived of basic needs. For my brother and me there was no school and the only entertainment was taking a walk. It was unbelievable the number of dead people you saw in the streets. When we came home, after a walk it was mandatory that we took off our clothing to search for lice, because they were the ones carrying typhus and typhoid fever. The only way you could survive was by supplementing your diet with things brought through the black market. But you can imagine that if the sellers were risking their lives to obtain these things, then the price is going to be extremely high. So it was no secret in the family that eventually our financial resources would run out and we would face the same situation as others One of my family’s important assets was a farm – large by Polish standards – near the little town of Kosow. Dad became friendly with a local family, the Zylberman family, also farmers. When we were in the Warsaw Ghetto, Dad and Mrs Zylberman corresponded with each other. Mr Zylberman was saying, “I don’t understand why things are so bad because things are normal here.” His suggestion was that we should try to escape and go to their house, live with them and maybe help with the farm chores. There was a street-car that actually traversed the ghetto area. The rules were that when it entered the ghetto area, all the passengers had to get off. While it travelled through the ghetto you could get on the street car if you had the fare, but as it was leaving the ghetto, everyone would get off and the streetcar would exit.

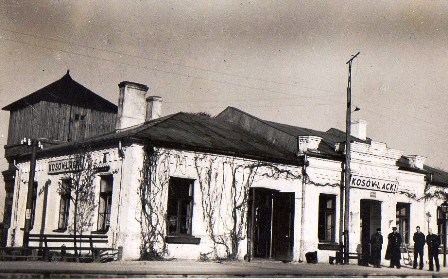

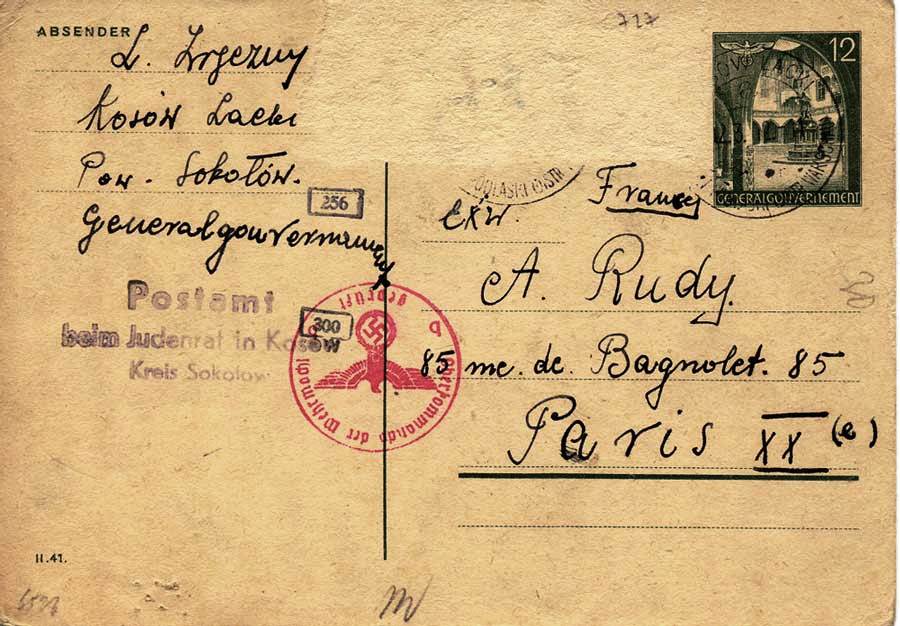

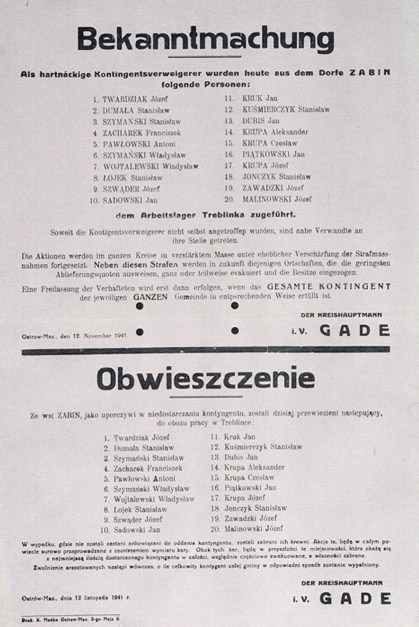

There was a man who had the right contacts and by bribing him we got on the streetcar. At the right time, the arm-bands identifying us as Jews came off, everybody looked the other way and we were on the other side. We reached the little town of Kosow partly by walking and partly by train. When we arrived, we found that Mr Zylberman had not exaggerated – it was a very pleasant surprise for us because things were absolutely normal there. We didn’t know it at the time but a tiny Polish village nearby, by the name of Treblinka, had been selected as a death camp. While we were living with the Zylberman’s and helping them with their farm chores and maintaining a semblance of a normal kind of life, the letters and postcards we had been receiving from our grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins in the Warsaw Ghetto all of a sudden stopped coming. Then we started receiving people who had jumped off transport trains who were telling us a tale of horror, that the transports from Warsaw were going to this camp of Treblinka. Another sign was that some bodies were burned in the fields and if the wind blew in the right direction the odour from this horrendous place was just unbelievable.

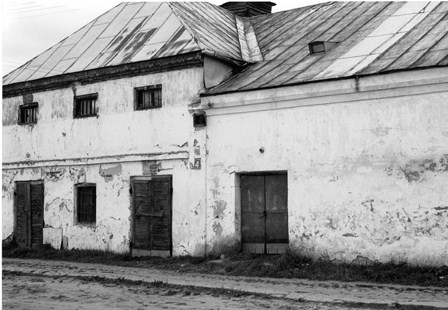

So all of a sudden things fell into place, and people began to realise why Kosow was being treated differently from the Warsaw Ghetto: we were a captive audience, they were going to get us when it was convenient for them and in the interim we were a convenient source for the labour pool. And this is the point when Dad decided that the only way for the family to survive was to go into hiding. Once Dad had decided we must go into hiding, with the help of two young men, a farming family was found in the vicinity of Kosow willing to take a chance. The reward of the Goral family was to be our farm. The plan was to dig a shelter inside of a barn. It was a large family living inside that small farmhouse; Mr and Mrs Goral, their son and his wife, and three teenage daughters. The shelter was to be big enough to house eleven people including the four of us. All the digging had to be done at night and carried to the fields by hand, but once it was done, it was unbelievable – you had no idea there was anything unusual about that barn. The walls of the shelter were lined with straw, there were branches on the floor to keep water from coming up, and there was as trap door which, when lifted up, was still inside the barn. We actually went into the shelter in the winter of 1942/43 and stayed there twenty months until liberation came. A mother and daughter were in hiding with us. What nobody knew when they joined us in the shelter was that the young woman was pregnant. We were twenty months in that bunker and it takes only nine months to deliver a baby. Everyone knew the serious implications, but didn’t want to think about it; but the lady was getting bigger and bigger and obviously one day she was going to deliver her baby.

At the same time Mr Goral’s daughter-in-law was carrying her baby and finally the day came when the delivery of the Goral’s baby took place. It was a very difficult birth; a midwife had to be called and she had a little boy who died at birth. A couple of days later a baby girl was born in the bunker. There was nothing wrong with the little girl, it was an easy birth, the only problem was that she did what all new-borns do – she cried. And of course the lives of eleven souls rode on the ability of keeping the whole thing secret and quiet; everybody realised that it would be impossible to keep the baby in the shelter. The idea was raised that maybe a swap could be made with the woman upstairs, but as there was a midwife involved and this was a girl, not a boy, the idea did not fly. And so the conclusion was that the baby had to die. And Mrs Goral concocted a potion of poppies – opium- which the mother had to spoon-feed to her baby. And the babe just simply dozed off and died, never regained consciousness. The whole thing had a tremendously traumatic effect on the people in the shelter. My brother and I took it particularly hard – to witness this kind of thing was really a terrible, terrible experience.

The front line on the Eastern Front was moving in the right direction. I’d hear the sounds of the artillery, bombs and shooting all coming from the east. One day it sort of rolled over and started coming from the west. Mr Goral opened the trap door, “They’re gone.”

That was the day of liberation. We left the bunker and were just so absolutely grateful to the Soviet troops. It was late summer, early fall 1944, a very hot day. We were just sitting in amazement, watching all these soldiers march by.

And they were looking at us, probably more amazed than we were looking at them. You can just imagine what you looked like when you haven’t seen the sun for longer than a year and a half.

Immediately after our liberation by the Russians one of the men in the bunker, a native of the town of Kosow, was gunned down in the street of his home town when he returned. Of course it was obviously to keep him from claiming his house and properties; so again greed and possibly anti-Semitism caused that.

In 1946, on 4 July to be exact, a group of survivors – I think the number was forty-two – who came back to their town of Kielce, were massacred. This was a year after the war ended and it was a signal to Dad that there was no future for us in our town of Kosow and our country of Poland and we had to leave; because if those things can happen after the experiences of the Second World War, then our lives were not safe. That was the signal to many other survivors who did the same thing.

The majority simply packed up and left and many of them emigrated to what later became the State of Israel, and many to the United States or Canada or South America.

In our case it was a case of simply getting on a train and heading for the border and, eventually after many more experiences, we came to Iowa, in the United States, in February 1951.

Source:

Holocaust Historical Society Bundesarchiv Yad Vashem Forgotten Voices of the Holocaust by Lynn Smith published by Ebury Press 2005

Copyright. Victor Smart H.E.A.R.T 2012

|