Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| |||||||

Hershl Sperling Personal Testimony of the Treblinka Death Camp

Hershl Sperling and his family lived in the Czestochowa ghetto on Wilsona Street near the ghetto wall. What follows below is his account of the deportation and incarceration in the Treblinka death camp

In September 1942, the deportation of the Jews of Czestochowa began. We had already sensed it coming weeks before. The town was surrounded by SS units. We are all woken from sleep before daybreak by the noise of wild shooting, vehicles and people screaming and wailing.

We look out into the street and see the SS men savagely bursting into people’s houses and driving the occupants out into the street with blows from their rifle-butts. We watch them arbitrarily dividing up people after a superficial glance at their work-permits; a very small minority of them is assigned to work, and the rest are transported away en masse.

Some kind of premonition tells us that this is the route to death, and we decide to hide in the bunker, which we had already prepared. Some elderly Jews join us and we lie together, hidden in the bunker, cut off from the world, and discus our dangerous situation. We don’t dare go out in daylight, but at night we creep out into the fields to find something to eat. There are cabbages, turnips, and other vegetables. We bring them back and cook them on an electric stove. At night when it is dark, we enter the houses of the deported Jews and search through the abandoned rooms.

Our bunker is discovered almost at the end of the period of deportations. Whether we were betrayed by someone, or whether it was purely chance, we don’t know. The commander of the deportations, Degenhardt makes a personal appearance and commands us all to leave the bunker. We all comply, because we know if we were discovered during a second search, it will be certain death. We are taken to Pszemiszlaver Street, where the last deportees are just being taken away.

Of the seven thousand Jews who are rounded up here, three hundred men and ten women are assigned to a work – detail in Czestochowa. The remainder are forced into a large factory yard. They are destined for the furnace in Treblinka.

On the day before the deportation one loaf is distributed to each person, for which they have to pay one zloty. This is a carefully worked out plan of the Germans. According to the number of zlotys they will know the number of people and can estimate how many wagons they will need, and how many people should be loaded into each wagon. At four o’clock in the morning the deportation began. Everyone has to assemble. Everyone has to take off their shoes, tie them together and hang them over their shoulders. Then begins, silent and barefoot, the march to annihilation. At the exit to the factory yard a box has been placed.

Under threat of punishment by death, everybody has to throw all their valuables into it. Hardly anyone does it. As they marched on, however, their fear grows. They have second thoughts about it and from all sides valuables, foreign currency, money and so on are dropped by the wayside. The route of the death-march is littered with Jewish possessions.

When we arrive at the train, the SS shove eighty to hundred people into each of the wagons. The disinfectant calcium chloride is scattered liberally into every wagon. Each wagon receives three small loaves of bread and a little water. Then the doors are pushed shut, locked and sealed, Ukrainian and Lithuanian SS stand guard at the steps of each wagon. We are shut in like cattle, tightly crammed together. Only a tiny bit of air comes in through the one small wire-covered window, so that we can hardly breathe.

The calcium chloride hardly helps combat the unbearable smell, which gets worse all the time. Some women faint and others vomit. The natural functions also have to be performed in the wagon, which makes the situation even more terrible, and on top of everything else we are tormented by a dreadful thirst.

We become utterly desperate and keep begging the SS guards to bring us some water. They refuse for a long time but eventually they agree to give us some water, but only for money. We managed to collect a few thousand zloty and give them to the guards. The SS take the money, but no water appears. Thus in pain and torment, the journey drags on until we reach Warsaw. Then our train is shunted into a siding. It’s not until the following morning that we travel on to Malkinia, seven kilometres from Treblinka.

Here we see Poles working in the fields and try to communicate with them. We just want to find out what our fate is going to be. They, however, hardly lift their eyes from their work, and when they do, they just shout one word at us: “Death!”

We’re seized by terror. We can’t believe it. Our minds simply won’t take it in. Is there really and truly no escape for us? One of the Polish workers mentions burnings, another, shootings, and a third – gassings. Another tells of inhuman, unbelievable tortures. An unbearable state of tension mounts among us, which in some cases even leads to outbreaks of hysteria.

However, we don’t have much time to think about all this. A special locomotive takes away twenty of the sixty wagons which made up our train. After five minutes it comes back and takes another twenty wagons. A woman beside me is wailing and moaning: “They’re murdered already, they’re dead, dead, dead..... My God, why has this happened to us?” An icy horror comes over me, and I clench my fists helplessly.

And now the last twenty wagons are being moved. I am in one of them. Slowly we roll on. One can clearly see that the forest here has recently been dug up. Full of trepidation, we roll towards a huge gate guarded by a large number of SS with machine-guns.

The train stops and the escort is commanded to get out and wait there. Then the gate opens and the locomotive shunts all the wagons into the camp. It remains outside. The gate closes behind us. The wagons roll slowly towards the big ramp. Round about it stands an SS unit, ready to receive us with hand-grenades, rubber truncheons and loaded guns.

Now the doors of the wagons are flung open and, half-fainting, we are driven out onto the ramp. We can hardly stand, and desperately gulp deep breaths of the fresh air. There is terrible wailing, screaming and weeping. Children are searching for their parents. Weak and sick people are begging for help.

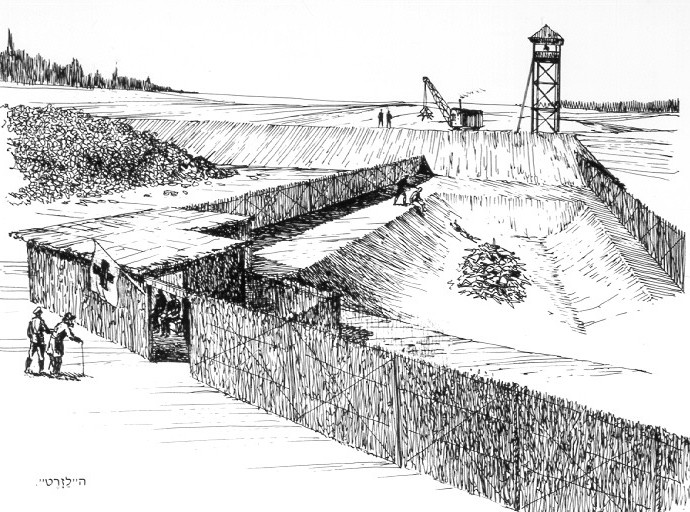

Desperate women are tearing out their own hair. But straightaway the SS rush at us and force everyone to move on. The stragglers – the old, the sick, the weak and little children without parents – are either lifted onto stretchers by a squad wearing Red-Cross armbands, or helped along. They are all brought into a large building, the so-called Lazarett or infirmary. A fire burns in the middle of the room. On one side stands a long bench.(1) The old, the sick and the children have to strip naked, supposedly for a medical examination. Then they are made to sit on the bench, one beside the other, facing the fire. When they ask what the fire is for, it is explained that it is to keep the room warm so that none of the sick people should catch cold.

Then a group of men armed with machine-guns appears behind them. A short muffled burst of machine-gun fire is heard- and, shot through the head, they all fall into the burning fire. Another work-squad comes immediately and lays new branches on the dead bodies, because new victims are already waiting to be annihilated. While this was going on, the savage SS herded the rest of the men and women down from the ramp with their truncheons and drove them through a gate leading to a large square. The square is surrounded with barbed-wire carefully camouflaged with leafy branches.

On the right stands a large open barracks, the women’s barracks. On the left stands, another high, open barracks for the men. A command rings out: women to the right, men to the left. There are indescribable, heart-breaking farewell scenes, but the SS drive the people apart. The terrified children cling to their mothers. At last the people have been divided into two groups. Then comes the order; undress, and tie your clothes up in a bundle, tie your shoes together in pairs. The huge crowd just stands there as if waiting for something, until the savage SS let fly with their rubber truncheons and force the people to undress.

Some more slowly, some more quickly, with greater or lesser degrees of embarrassment, the men and women undress and lay their clothes aside. Some still try to exchange a word with the Jews who are working in the squads in order to find out something about what awaits us. We are told the terrible truth; from this camp no one comes out alive, and there can be no question of escaping; we have come to our death. But we simply can’t believe it. The human being is too attached to life, even if the truth of these predictions should be confirmed a thousand times.

At last all the men and women are undressed. We are dying of thirst and scream for a drink of water. But we are not given it, even though there is a well in the middle of the yard, as if to spite us.

Now the naked women are driven into the barracks. They do their best to cover their breasts with their arms. At the entrance to the barracks a shearing-squad awaits them. With one cut all the women’s hair is hacked off and immediately packed into waiting sacks. Then the women are assembled in groups and, with their hands above their heads, they are led through a back door into the death camp.

Meanwhile the naked men are forced to pack up all the male and female clothing. Everyone has to carry a heavy load and go at a running pace through another gate into a second huge square surrounded by long, single-storey barracks. The clothing is laid down by the barracks.

Then everyone has to get into line, their hands above their heads and at a marching pace, to the rhythm of the beating rubber truncheons, we go back to the main square. There the men are made to run many times round the square until they are completely exhausted. This is so that, when they are marched to their death they will be so tired that they will not be able to offer any resistance in the death-chamber.

Finally everyone is driven into the men’s barracks and towards a door which leads to the death camp. At the very door 30 men are pulled out, of whom I am one. We are divided into five groups with six men in each. A couple of workers are assigned to each group. We have been chosen to form the work-squads in the camp. For the meantime we are safe.

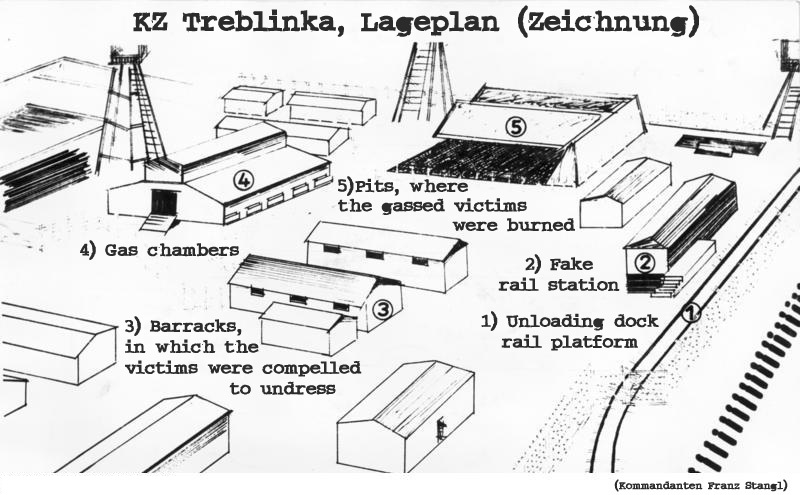

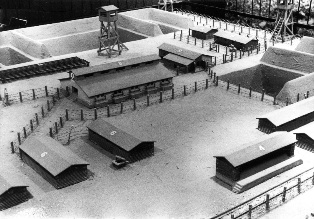

Treblinka consisted of two camps: Camp I, which received the transports, dealt with the plundered goods and prepared the victims to be taken to their deaths; then there was Camp II, the so-called death camp in which the swift and systematic annihilation of the people who had arrived on the transports took place.

I was in Camp I, where the work was carried out by various squads. There is the “blue” squad – its members wear blue armbands and have responsibility for the newly arrived transports at the ramp. This squad has to cleanse the newly arrived wagons of their dead bodies, filth and excrement as quickly as possible. The squad works with brooms. Each pair of workers has to clean out one wagon in ten minutes.

Then there is the red squad – men with red-cross symbol. Their task is to carry the old, the sick and children up to the age of six, or those who have lost their parents, on stretchers or in their arms from the ramp to the “death-infirmary.” Apart from these there were also special transport-squads, train-squads, sorting-squads, barracks- camouflage squads and also squads of carpenters, tailors, shoe-makers and so on. A Kapo was assigned to be in charge of each squad. He was responsible to the Lageralteste (senior camp inmate, or elder).

I belonged to the sorting –squad, which had to sort the discarded clothing into better and poorer quality and put them into the appropriate sections of the barracks. Every garment was minutely examined to see whether any valuables were sewn into or hidden in it. From each garment the Star of David had to be removed as carefully as possible so that no one could see it had belonged to a Jew. Each tin of shoe-polish, each pocket-torch or belt is prised or cut open to find anything of value which might be there. Watches and gold are put in separate piles. The following things are also put in separate piles; diamonds, rings, gold roubles, gold dollars and so on.

The collection and sorting of pictures is particularly strictly controlled. For the crime of taking a picture to keep, a Jew was punished by death. Mass shootings took place simply because one of the Jews had hidden on his person a picture of his wife or near relative. When each bundle was tied up, the Jewish sorter had to put a piece of paper with his name on it in the bundle, so that it would immediately be known which individual to punish for the smallest breach of the regulations.

I can still see before me the punishment that was meted out to a nineteen-year old boy who had forgotten to remove the Star of David from one garment. He is shot dead on the Appellplatz before the eyes of the assembled work –squads. He is forced to look directly into the gun –barrel. For making a movement of his head when the final command is given, he gets two brutal blows to the face. A few seconds later, he falls to the ground, his head shattered and is quickly removed. When each order for clothes comes in, the carefully sorted and packed stolen clothes are sent away. Usually a whole transport will depart with one article. There goes, for instance, a transport consisting entirely of suits, another consisting entirely of women’s silk dresses, a third of shoes and so forth.

Gold is loaded onto lorries and taken away separately. The SS units become enormously rich. As compensation for the gruesome work in the camp, they are granted four weeks’ leave and always travel dressed in civilian clothes. Each time, they take with them about ten suitcases. They take the best and most expensive clothes and the most beautiful gold and diamond jewellery for their families. Between Camp I and Camp II, three huge excavators work day and night, piling up huge mountains of earth between the two camps. Day and night, the bright glow of the burning bodies rises up to the sky. It is visible for miles.

When the wind blows in the direction of our camp, it brings such a terrible smell that we can’t manage to do any work. Only when the wind changes direction can we start doing our normal work again. It was strictly forbidden to cross from one camp to the other. In the early period the food carriers used to come to us from Camp II and bring us all the minute details of the cruel deeds that were being perpetrated there. When we heard about them we choked and our heads whirled feverishly. It often took hours before we could start working again. The tears running down our faces did not alleviate our helpless rage and our searing pain.

The food-carriers describe to us how the path to the death camp goes through a garden. Just before you come to the death-shower, there is a hut, where everyone is instructed once again to relinquish money and gold. This is always accompanied by the threat of punishment by death. The greed of the Nazis is such they won’t let even the smallest item of any value slip through their hands. At the shower room of death, which is adorned only by a Star of David, the victims are received with bayonets. They are driven into the shower rooms, prodded with these bayonets.

Whereas the men go into the showers in a fairly restrained fashion, terrible scenes take place among the women. Showing no mercy, the only way the SS can think of to quieten the women is with their rife-butts or bayonets. When all the wretched victims have been forced into the showers, the doors are hermetically sealed. After a few seconds, uncanny, horrifying screams are heard through the walls. These screams go up to heaven, demanding revenge. The screaming becomes weaker and weaker, finally dying away. At last everything is completely silent.

Then the doors are opened, and the corpses are thrown into huge mass graves, which hold about 60 to 70 thousand people. When there was no room for any new victims in the mass graves, there came a new command to burn the dead bodies. They would dig out a deep trench, and throw in a few old trunks, boxes, wood and things like that. All that is set alight, and a layer of corpses is thrown onto it, then more branches and more corpses and so on. Later the order was given to dig out the dead in the mass graves, and burn them too. When the corpses, which are already decomposing, are dug up, a considerable amount of money and valuables is found in the stomachs and guts of the victims. This proves that even when looking death in the face, the Jews still believed in life.

The smell of blood, the dreadful stench of the decomposing and burnt corpses wafts death itself over the workers of the death brigade. No one can stomach this work for more than a few weeks. Even the SS units are changed every two weeks and sent on immediate leave. Even the murderers themselves cannot bear this diabolical bestiality. Later on, communications between the work-squads from the two camps was forbidden. Even during the hand-over of shoes or clothes by the squads of Camp II, our people were only allowed to go up to the border between the camps. There the workers from the death camp would hand over the fearfully stinking, blood-soaked clothing.

Once a large- scale typhus epidemic broke out in Death- Camp II. In order to prevent the spread of the epidemic, the sick people were separated from the others, stripped naked and only allowed to wrap themselves in a blanket. They were driven outdoors and chased up the high piled- up mounds of earth by the death chambers. There the SS opened fire on them, and the bodies rolled down into the fires which were already burning in the ditches below. Shortly after this, barbed wire fences were erected between the two camps. This work was carried out by the work-squads of both camps. Once again we had the opportunity to pour out our woes to each other, and to lament our terrible fate.

New transports arrive at Treblinka all the time. Sometimes there is a break of a few days. But on average ten thousand people per day are murdered in Treblinka. There was one day in fact when the human transport reached the figure of twenty-four thousand. The Polish Jews, who in the early days had been sent only to Treblinka, already sensed in advance what their fate would be. It was as if they understood that Treblinka meant the end for them, and they let themselves be handled like animals for the slaughter. They are beaten while they are being put into the wagons, while they are being driven from the ramp, when they are getting undressed and when they are going to their death.

Only once did any of them put up some resistance when some Jews in a transport from Warsaw managed to smuggle in some revolvers and hand-grenades. They did not, however, achieve any great success. Just a few wounded SS. The punishment for the rebels was very severe. Oberscharfuhrer Franz deliberately kept them alive in order to beat and torture them until death released them. Those who managed to commit suicide were mainly doctors and their families; they secretly brought cyanide capsules with them.

The transports of German and Czech Jews were received with all kinds of tricks and pretences which masked the true situation. On the platform signposts were put up; “To Bialystok,” – “To Wolkowice.” There were also signs saying “Platform 1,” Exit,” To the Toilets” (2) The people were not beaten on arrival and even the commands were given in a polite and friendly fashion. One woman who has brought a lot of suitcases with her does not want to go into the Lazarett, is given assurances that her luggage will be sent on after her. She, however, won’t hear of it; all her life, she says she has worked for the things she has brought with her and she isn’t going to entrust them to anyone else.

Unterscharfuhrer Sepp (Hirtreiter) (3) finally loses “patience” with her and cannot resist using his whip. Then she leaves her suitcases and goes off weeping and wailing to the Lazarett with the man from the red brigade. On the way there she tells him that she is hoping to have a good rest here in order to get her strength back. The SS take even more care over the transports of Bulgarian Jews. They arrive in nicely appointed passenger coaches. Their trains have coaches with wine, bread, fruit and other foods. The SS make a real banquet of these delicacies, and the Bulgarian Jews go with carefree minds to their death. They are given soap and bath-towels. Whistling to themselves and waving their towels they go merrily to the death camp.

The Gypsies are not brought in wagons but in small groups on horses and carts. They are not sent to the death camp, but are brought to the Lazarett where they are shot and burned. Only once did Jews leave the camp alive. The Front had demanded women, so one hundred and ten of the most beautiful Jewish girls, accompanied by a Jewish doctor, were sent off.

In the camp, which in any case was so full of terrible cruelty, there were individual SS men who were famous for particular “specialities.” Unterscharfuhrer Sepp, for example, had the habit of choosing small children from the newly arrived transports, and skilfully splitting their little heads with a spade.

Untersturmfuhrer Kurt Franz – the deputy camp commandant – used to pick out people from the work-brigades every day, and under various pretexts (working too slowly, giving hostile glances and so on) he would order them to strip naked and then beat them to death with his riding whip. But the absolute demon in our camp was Unterscharfuhrer Miete (Sperling called him Mutter). He has to have several victims every day. So he goes and picks someone at random and searches that person’s pocket. If he finds something, he beats the victim with extreme brutality until he falls down dead.

If he doesn’t find anything, he looks at the person for a moment and says: “You have an evil look about you – you definitely think too much; therefore you are dangerous and must die.” After this explanation Miete beats his victim until the latter shows no sign of life.

Unterscharfuhrer Suchomel, the head of the barracks, had a special interest in the “gold-Jews.” These were Jews who sorted the gold and valuables. Suchomel constantly used to send home huge amounts of gold and other valuable objects, and the “gold-Jews” who knew about his plundering were not allowed to remain alive for long. I only once met an SS man in Treblinka who was unwilling to participate in the inhuman deeds. The first day he was there he found everything so incredible that he took a Jew from a work-squad aside and asked him to tell him the absolute truth. “Impossible, impossible,” he kept murmuring, shaking his head slowly as he spoke. From that day on he was never seen again.

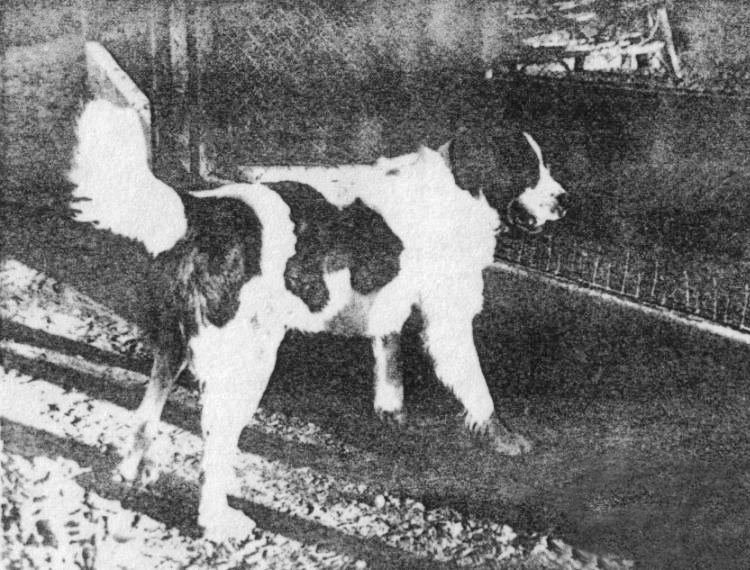

Our life was a constant round of fear and pain. We often envied those who had it all behind them. Death is constantly before our eyes. The food is never adequate and all the time we have to work out methods of stealing little bits of food such as bread, potatoes and so on from the newly arrived transports. We steal, even though we know we run the risk of suffering a terrible death. For smoking you are shot. One man was killed because he was so cold that he lay down on a heap of clothes and covered himself with a torn fur: for that crime he was torn to pieces by the dog Barry which was specially kept for such things. The man’s overseer, who had not reported him, was killed on the spot by Unterscharfuhrer Franz with one blow to the face.

Our working hours were from six in the morning till six in the evening. We had one hour at midday. In the evening, when we are dead tired, we have to sing various songs to the accompaniment of an orchestra, first the “Treblinka March,” then a Polish song which tells of a mother who sells her child in order not to die of hunger.

In the early days Jews used to try to escape from Treblinka almost every day, but then the control became very strict. For trying to run away, people were hung up by their feet on a high pole until they breathed their last in terrible agony. Once two Jews were hung up like this. As they hung there, they kept screaming at us: “Run, run all of you! In the end death awaits you too. Don’t be fooled because you’ve got enough to eat today – tomorrow you’ll share our fate!”

Reporting sick is not really a possibility either, you are only admitted to the hospital with a fever of over 40 degrees, and anyone who is ill for more than six days is shot. In general, death by shooting became a daily occurrence. The Jews who had been shot were replaced by new workers from the latest transports.

Our situation becomes more dreadful every day. Day and night we think about ways of avoiding our terrible fate. Then suddenly, a chance happening came to our aid. In the camp there was a Jewish doctor, Chorazycki, who used to treat the SS too. Once Unterscharfuhrer Franz comes to be examined by him, he suddenly notices the doctor’s bulging wallet. He asks the doctor about the contents of his wallet and the doctor answers him by grabbing a surgical knife and plunging it into Unterscharfuhrer Franz’s body.

The latter runs around the yard, and the doctor pursues him with the knife. Instantly, Ukrainians appear from every side and throw themselves on the doctor. He manages, however, to swallow poison. Straight away all the doctors in the camp are alerted. They do their best to keep Dr Chorazycki alive by pumping out his stomach. When that doesn’t help, Franz takes revenge by taking his riding whip and beating the dying doctor until he is completely dead.

The next day a search is made of the belongings of the Jewish Kapo(4) and a sack of gold is found among his things. He is shot dead on the spot. The tension mounts every day. We Jews realise that it is now a question of life or death. A while ago we buried money and valuables, knowing that without financial means we cannot even think about running away. We have also managed to procure a few weapons. Now we have to organise the attempt. Engineer Galewski, the Lageralteste, the new Kapo Kurland and Moniek, the Kapo of the yard-Jews were the leaders of the uprising.

A fourteen –year old Jewish boy steals into the Ukrainian guardroom at night and removes weapons, bullets and several machine-guns. The arms are divided out, and the day on which the revolt will be launched is decided upon. As far as I remember it was a day at the end of the summer 1943.On that day the terrible Oberscharfuhrer Franz and forty Ukrainians are due to leave the camp to bathe. At six in the morning a shot is to be fired as a signal that the uprising has started. There is enormous tension among the Jews.

At four in the morning we find out that our plan is in danger of collapsing. Oberscharfuhrer Kuttner has arrested twenty Jews whom he found in possession of gold. Finding Jews with gold or valuables was a sign for the SS that people were planning to escape and therefore had to supply themselves with valuables so they could live illegally. In such a case the SS would instantly carry out a search of the other Jews in the camp.

It is not long before we see the SS taking these twenty Jews off to the Lazarett in order to kill them. After a short discussion we decide to launch the revolt this very minute.(5) A hand –grenade is thrown at Oberscharfuhrer Franz (6) , the signal to fight is given and the Ukrainian SS open heavy fire on the Jews. But the Jews remain firm, throw hand-grenades and position their machine-guns. Some Ukrainians fall and the thousand or so Jews in the camp (7) break through the fence.

On the other side of the fence a path leads into the woods. Heavy fire from the Ukrainians accompanies the escapees. Some are hit, but the great majority reach the woods in safety. A frenzied activity begins. All the telephone lines are cut, the vehicles are disabled, so they can’t be driven; whatever petrol we can obtain is poured out and lit; the death camp Treblinka begins to burn. Pillars of fire ascend to the sky. The SS shoot back chaotically into the fire.

A mad pursuit begins. The Jews divide themselves into very small groups. I am with three other people. Now there is one command: forward, forward! We manage to get twelve kilometres away from Treblinka. By day we dare not move, for fear of being seen. We hide in inaccessible places. At night fear drives us on. But we are beginning to be tormented by hunger. We wonder whether we still have any chance of staying alive, or whether it would not be easier to take our own lives. One of us talks of hanging himself . But in the end the will to live is stronger.

Being the best Polish speaker, I creep into the nearby village to get something to eat. Slowly, hesitatingly, indecisively, with a pounding heart, I come out of the wood and approach a peasant house standing on its own. It is about 30 kilometres from Treblinka. Raising my eyes to heaven and praying, I step onto the threshold of the house. One glance at the woman tells me that she realises what I am. “You must have escaped from Treblinka,” she exclaims. The state I am in, my clothes, and above all the expression of desperation on my face have all given me away. I am prepared for the worst.

But the woman reassures me, saying that I mustn’t be afraid, that she will help me as much as she can. She can’t hide me, however, the SS are snooping around and searching all the villages in the area. She is not prepared to expose herself and all her family to mortal danger, she gives me bread and milk and tells me to come back at eleven o’clock at night.

At the appointed hour, all three of us are in her house. This time her husband and daughter are also there. We discuss the situation and decide the best thing would be to go to a particular place and jump onto the roof of the moving train. At that particular point the train moves with a speed of ten kilometres per hour at most. We have no other way out and we agree to try this. They give us a substantial supper and bread and eggs for our journey. As an expression of our gratitude we leave them twenty gold dollars.

Under cover of darkness we set out on our way. We come to the agreed place but we decide not to jump onto the roof of the moving train after all, because we might fall through into the train itself. Instead, we carry on, on foot, until we reach Rembertow. We have decided to go on from there by train, but we haven’t any Polish money. We sell a diamond ring worth twenty –thousand zlotys to a peasant, getting only five-hundred zlotys for it. Quaking with fear we buy our tickets and manage to get to Warsaw safely.

A great number of the escapees were soon killed or captured. The suffering of the others was to be long and terrible. Only a few of the escapees from Treblinka, round about twenty, got to freedom. I later met some of them personally in the American zone of Germany. They were: Shmuel Rajzman from Wegrow; Kudlik from Czestochowa; Schneiderman who now lives in Foehrenwald Camp; Turowski, who now lives in Berchtesgarden.

Notes

(1). The Lazarett was introduced by Christian Wirth when Treblinka was re-organised during August – September 1942. The Lazarett was surrounded by a tall barbed-wire fence, camouflaged with brushwood to screen it from view. Behind the fence was a big ditch which served as a mass grave, with a constantly burning fire.

The Lazarett area also contained a small booth that served as a shelter in bad weather, and a bench – people who would have slowed down the extermination process, the sick, the elderly, unaccompanied children were killed by a bullet in the neck. The three Jewish inmates on duty here wore Red Cross armbands and the Red Cross sign was prominently displayed on the booth

(2) During Christmas 1942, part of the sorting barracks was fitted up to look like a railroad station building, complete with a station clock, ticket windows, posted train schedules, arrival and departure signs and the station name Obermajdan – all designed to fool the Jewish victims that they were in a proper transit camp not a death camp.

(3) Josef Hirtreiter nicknamed “Sepp” was the first of the Treblinka SS personnel to be brought to trial. He was tried in Frankfurt am Main and on the 3 March 1951 was sentenced to life imprisonment for murdering Jewish inmates, many of them children.

(4) The Jewish Kapo is Rakowski, who also deputised for Galewski as Camp Lageralteste, was shot at the Lazarett for stealing gold and valuables.

(5) Sperling is incorrect re the timing of the revolt. Oberscharfuhrer Kuttner at around 3:30 in the afternoon on the 2 August 1943, discovered a Jewish prisoner in the ghetto area, searched him and found he was carrying large sums of money.

Fearing the inmate would betray the uprising, Kuttner was shot and wounded at about 4pm and this signalled the start of the prisoner revolt at Treblinka.

(6) Kurt Franz the deputy commandant was not present in the camp when the revolt started - he was swimming in the River Bug with some other SS men and a party of Ukrainian guards.

(7) The number of inmates in Treblinka was approximately 850 of which approximately half managed to break out of the camp, and that about 100 inmates escaped from the Treblinka camp and adjacent vicinity.

Sources: Treblinka Survivor – The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling by Mark C Smith published by the History Press 2010 Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka by Yitzhak Arad published by Indiana University Press 1987 The Death Camp Treblinka edited by Alexander Donat published by Holocaust Library New York 1979 Bodleian Library Ghetto Fighters House Holocaust Historical Society Yad Vashem Polish State Archives (Naczelna Dyrekcja Archiwów Państwowych)

Copyright 2012 David Adams H.E.A.R.T

|