Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| ||||||||

Yakov KaperHis Account of Life in Kiev 48 Melnikova - Syrets Camp – Babi Yar Selected Extracts from the Thorny Road

Part 1 Captured by the Germans

I was born in a small town named Lubar in the Zhitomir region in 1914. From 1935 to 1937 I served in the Red Army in Belaya Tzerkva in the 185th Turkestan Infantry.

I completed the regimental school for junior commanders and received the rank of sergeant-major. After I was demobilised from the army, I moved to Kiev and started to work as a carpenter in the co-operative Kievkhudozhnik.

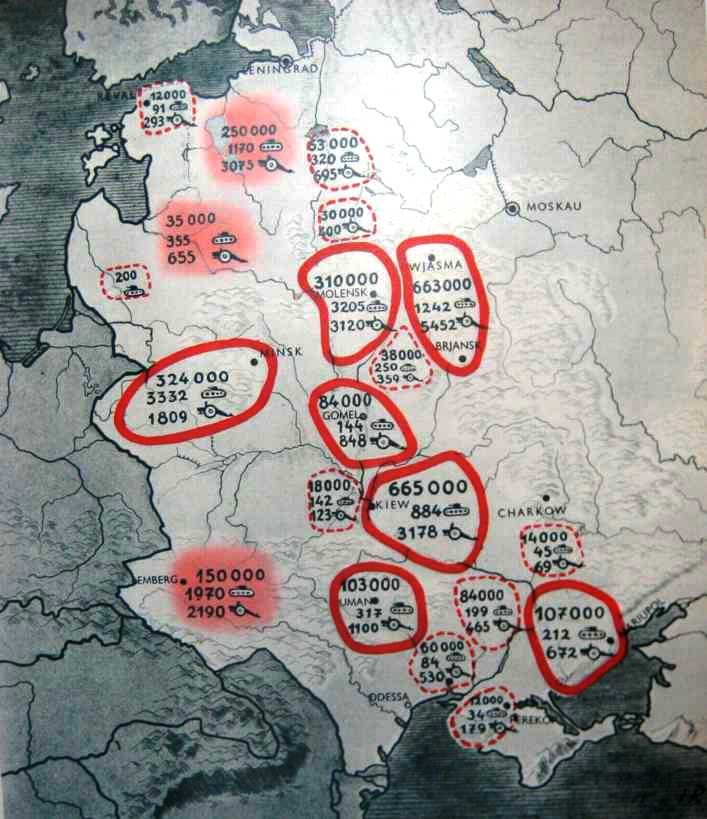

When the war began I was called for military service again. We guarded military projects; at the beginning of August we were transferred to the village of Novy Petrovtsky where we dug in and set up to defend the area.

One night we were alerted and directed towards the town. From the distance we noticed a column of motorcyclists, but we thought they were our soldiers. When we entered one of the houses we heard some shooting.

We hurried outside and saw our soldiers shooting at the German motorcyclists, we ran towards our location but when we reached it, we saw that some of the soldiers had been killed and the rest had run away.

We moved on but our soldiers kept on disappearing because of rumours that the Germans had announced that anyone who surrendered on his own will would not be punished, I understood that we had to reach our detachment in Darnytsa.

In a courtyard I saw two women and asked them for some water to drink, they brought me some and asked where I was going in my uniform, since I would easily be noticed by the Germans. They invited me to sleep at their house and said that I could go in the morning.

At dawn the hostess woke me up and told me to leave because the German soldiers were already there. If they found a soldier they would burn the house down, she brought a pair of old trousers and a jacket for me. She told me to change into those clothes.

There was a school nearby where many people were hiding from the bombings, when I arrived at the school there were many people, mainly women, teenagers and children already in the building. There also were some young people in both civilian and military clothes with them.

Very soon we heard some shooting, a column of German motorcyclists was driving by and one man in a militia uniform was throwing hand grenades at them. Afterwards the Fascists made everybody go into the street and started dividing us into different groups. I was placed into a group of young people, some who were still in uniform.

The order was given to shoot us, we were lined up and marched along the road, in the opposite direction another group of German soldiers led a column of military prisoners together with some civilians.

Hearing that we were to be shot, the officer of that column added six people to our group, among them was one Jew in civilian clothes carrying a violin. When he found out that we were going to be shot he started begging fot mercy because he was a violinist.

He took off his hat, threw it down and began to play his violin, until that moment I had been absolutely indifferent to the fact that we were going to be shot, but when that Jew began to play his violin, I felt something inside of me and tears began to stream down my cheeks.

The Germans started to taunt him, one German cried out Yid, then they ripped of his pants to make sure he had been circumcised, another German suggested that they snip him again. They all roared with laughter, somebody pulled out a knife and cut the violinist. Even now I remember the wild screams of that man, they shot him and drove us further down the road.

In the morning our group was taken to Kerosynnaya, as we were marching these people were throwing bread, tobacco, biscuits, sweets and whatever else they could to us, though the Germans did not allow anybody to come near the group.

In Kerosynnaya the Germans had set up an immense camp for prisoners, here too people threw whatever they could over the fence, we were forced to work every day, at the camp. The usual work was to stand in a line and pass shells up the hill from the Vydubetsky monastery. They served us gruel in the camp, but there was nothing to pour it in, so people used their hats, caps or different tins for it.

One day we were forced to line up and speaking through an interpreter, they ordered all the commanders and political commissars to step to the front. There were a lot of them and they were taken off somewhere. Then came an order for the Jews to come forward, I decided not to leave the line.

Du bist Jude? – Are you a Jew? – the German asked me.

Since I was afraid of being tortured, I admitted that I was, I was taken to the camp for Jews only. When I arrived I saw that all of the prisoners were lined up and a German ordered me to lie down. They started to beat me and the interpreter asked where the mines were located. At that time Kreshchatyk and other streets constantly were being blown up by mines that the Red Army had placed.

Later we were lined up again and driven into a big garage, but there wasn’t room for all of us, they started to shove and press everybody inside, we were packed in like sardines. The gates were closed: we could not move an inch.

We stayed like that for six days and nights, they did not give us food or water, many people died but there was no room for the corpses to fall, so they remained wedged between those left alive.

The only thing we could hear were screams for water, the odour was unbearable, next to me was my cousin’s husband Shindelman, and some other fellows who I had met there.

Everyone had a different opinion about our fate, some said that we would be let out, while others thought that the garage would be blown up together with us. At last the Germans opened the gates and ordered everybody over thirty-five to come out.

Before an hour had passed they began to take everybody who stood near the gates, it happened several times, we heard only the cars roar and didn’t know the people were taken away.

After those people had left there was enough space in the garage for those who remained. Through the holes in the sides we watched when the trucks came back and some clothes were unloaded from them. We realised then that all those who had been taken away were shot.

Again the gates opened and they ordered everyone to come out. I went out we were ordered to take the corpses out of the garage. All the trucks were full and I got into a truck with corpses. Our truck started, then made a turn and braked.

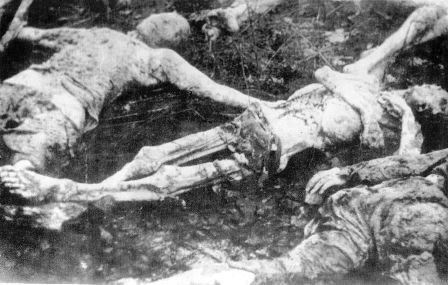

I jumped out of the truck, I don’t know how much time I was lying on the ground, they were shooting, when I regained consciousness I noticed that there were corpses not far from me, they had been shot on the side of the road.

I got up and thought it would be good to get to the forest in Pushcha- Voditsa. I was somewhere in Loukyanovka, a district of Kiev, when I was noticed by a policeman. He brought me to 33 Korolenko Street and reported that I was a Jew.

Nobody asked me anything but they made me clean the room with five other men until evening. That night we were locked in a cell in the basement. In the morning we were brought to the building of the Supreme Soviet, there we also did some cleaning and found some remains of food.

The next morning we were brought to 3/5 Institutskaya Street, before the revolution it became the home of the Secret Police. The Germans first blew up the building, but then decided to partially repair it.

After the mass shooting of Jews, they brought any Jew that was caught to that building to work on repairs. There were also some civilians who worked there, headed by the senior engineer Krynichny. They worked on heating and piping, in the evening they could go home and in the morning, they would come back to work.

All the prisoners were standing in line, we were ordered to join them, opposite us stood the Germans with automatic guns, and every soldier had a whip in his hand. One of the German officers was saying something and not far from there stood a Jew.

Later I found out that he was a Polish Jew who worked as an interpreter, he constantly clicked his heels and cried out Jawohl, then he translated the orders into bad Russian – “Whoever works badly will be shot!”

Everyone was given a hatful of dried bread and a scoop of coffee, it was our food for the whole day, then we were transferred into the cells in the basement, I got placed in a big cell with a Jew named Wolf.

I found out that the dried bread that we were given had been brought from Babi Yar, it was taken from those who were shot. All of the prisoners had dirty faces and clothes which were stained with blood. Every day at least 10 or 15 people did not return to the cell. They had been beaten to death with sticks, so they would not waste bullets.

In the camp I met my friend Yasha Shoikhet who I worked with before the war, we carried bricks, road-metal and sand on stretchers from morning till night. We had to do this while running; such work could not be handled by everybody.

The next day when the Germans announced the work assignments I ran over there, then I lost my confidence and turned back, a German noticed me and struck me on the head with his black jack and I fell down. He ordered to throw me into the ditch but while they were dragging me over there, Wolf came towards us. I was told that he had ordered them to drag me into the cell, I was thrown there and was lying there till everybody came back from work.

Wolf came up to me and asked me if I had any friends who could hide me, I told him I did, he said that I should go to the truck as a loader tomorrow, I objected because I did not understand how I could work with my bruised head. Wolf cursed and went away. I found a rag and bandaged my head. In the morning I ran towards that truck, there were four of us, Wolf came up. A German joined the five of us. We went to the brick factory in Kurenevka a suburb of Kiev.

The German went into the office and told the driver to guard us, the citizens looked at us with sympathy, we asked for food and they threw us beetroot, some bread, onions, or whatever they could. All this we put into the bags for gas masks that we had with us. All day we loaded and unloaded bricks. Nobody beat us.

During those days we lost many of our friends, including my fellow- townsman Yasha Soikhet, many new civilians who escaped from mass-shootings and Jewish prisoners were constantly being brought to the camp, here they worked, were tortured and were killed.

A civilian Lyonka Smulsky was our driver, he had to watch us since there were no other guards, he was warned that he was responsible for us, he told us that if any of us ran away, he would be shot and his family would also be killed and we would be found and caught all the same.

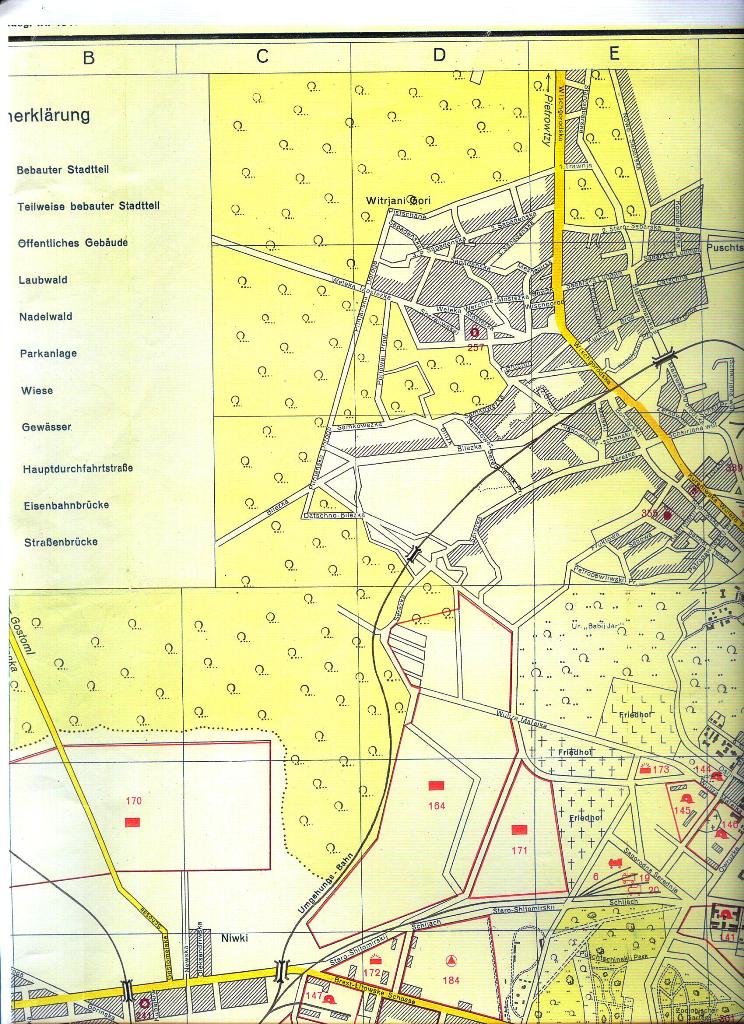

Once Smulsky got this assignment to bring coal to the house where the Gestapo soldiers lived in 48 Melnikova Street. All day long we had been bringing the coal there and in the evening we were taken back to Institutskaya.

Part 2 – 48 Melnikova Street

The next day we also did the same thing, Smulsky talked to the chief and he let us stay the night in the building on Melnikova Street, we were given soup, a lot of bread and taken to sleep, we spent several days there.

On Saturday evening, an acquaintance of ours, a civilian driver named Sharikov, came to us at the Gestapo, he said that Wolf had ordered us to come back to Innstitskaya the next day or else we would be shot. We needed to figure out how to get there, Sharikov said that he was not working and would come to escort us, so we agreed. On Sunday’s the Germans did not work, so he came and took us to Institutskaya.

We noticed that there work was in full swing; we did not know what to do and dispersed wherever we could. Philip Vilkes and I hid ourselves in the yard toilet. Lenya Ostrovsky and Senya Berland dashed towards one of the work areas. Then we also ran towards that area but we didn’t know what to do.

Suddenly a German came in, Philip and I grabbed a pipe and dragged it, the German took Ostrovsky away- half an hour later Ostrovsky came back pulling at his trousers, he had gotten 25 blows for bad work. Sharikov mainly worked on the gasenwagen, a bus designed to murder people by carbon monoxide, we found out about that when they made us clean out the bus after they had killed some people. It was filthy inside and we refused to clean it.

As a result, he invented an excuse to bring us back to Institutskaya, Sharikov’s father worked as a sanitary equipment fitter in the Gestapo house at 48 Melnikova. He was about sixty and he also made us clean the toilets, he used to complain to the chief that “none of the Yids wanted to work.”

When we learned from Smulsky that in Syrets there was a concentration camp and that people there suffered greater than in Institutskaya, we started helping them. In the evening Smulsky parked the car not far from the kitchen and we gave him bread in half loaves, so it would not attract attention. We did not know whom he gave the bread to, but after the second time we got a message of thanks with the signature Arkady Ivanov.

Danya Budnik repaired radios and we used to listen to the Radio Moscow, I repaired the windows and doors in the big bosses’ offices. The doors bore the inscriptions Hauptsturmfuhrer SS Doctor Schumacher, Sturmbannfuhrer SS Radomsky.

Once Budnik and I had to work in the flat of Radomsky , Budnik was ordered to fix a new chandelier and I had to hang curtains. He was a short plump man with red cheeks and by his side was his dog Rex, who was about his same height. We got scared and he called the dog back and locked it in the adjoining room, we finished our work and were ready to go when he opened a drawer, took out two packs of cigarettes and gave them to us without a word, we thanked him and left.

At the end of August several workers were brought to the shoemakers shop because the civilians couldn’t cope with the work, the clothes and footwear of the Gestapo soldiers needed to be repaired. Three men were assigned to the various works, among them was one strong man, Misha. He was about thirty or thirty-five and was a former seaman from the Dnieper fleet.

He arrived as a sanitary equipment fitter and together with him there was one more fitter, a young lieutenant still in military uniform, but without any badges of rank. Misha always addressed him as lieutenant. Boyarsky was the third one, he was a kind of Sotnyk (note: commander of 100 men – Ukrainian captain) but he requested to be assigned to Melnikova Street.

Former soccer players Misha Sweredovsky and Makar Goncharenko also ended up in the shoemakers shop, as well as the former master of the Syrets camp, Grigoryan Sergey.

The bandit Grigoryan used to kill our people and then told about it in Melnikova, I don’t know what Jews had ever done to him to make him hate them so much. Later I was told that during the occupation of Kiev he opened a shoemakers shop, the workers were supplied with bread to make them work at his shop, so he opened a small bakery.

Then he got a small truck, repaired it, made rounds of villages, bought hides and processed them himself, he was well in with the Kiev authorities, made high boots for them, shod them and they gave him a certificate for purchasing hides in the Kiev region.

But as soon as he went into another region he was caught, deprived of his truck and beaten so severely that he hardly remained alive. Thus he was sent to the Syrets concentration camp. Since he was very strong and showed hatred towards Jews he was appointed a master. When Kiev was liberated Grigoryan was caught and hanged.

Boyarsky was a former chief of the political department of the Kiev police and a former émigré, he had lived in Poland and Germany; he was assigned to Kiev, before Kiev even fell. According to him he was sent to the concentration camp for his ideas of an independent Ukraine, very soon he didn’t have to work at the Syrets camp and he became a Sotnyk. In 1943 he left together with the Germans when they evacuated the camp.

One period they started bringing wood to our premises in 48 Melnikova, after dinner I was summoned to the yard, when I went out I saw that there stood Sturmbannfuhrer Radomsky, Rottenfuhrer Lange and Pan Willi, as we called him. Pan Willi told me in broken Russian that it was necessary to build a big barn garage for five cars by the evening. He showed me the place, where the beginning and the end was and said that people would be brought over and I was to supervise everything in order to finish by the evening.

I was thinking about how to begin when suddenly a policeman ran up and said that his team was ready, so I saw a platoon of policemen with spades and axes and Pan Willi told me to give them the orders. I marked where to dig holes, some of them were to dig, others needed to tie up the poles and make a frame out of the boards. When the holes were ready I told them to lift the ready-made walls. We managed to bring them together and made a box. The barn was to have a lean-to that had to be made and gates and then everything would be ready.

On the next day again I was summoned, Radomsky and Willi were standing in the yard and talking and I saw him smile for the first time. I came up to him, after having removed my hat in advance and stood at attention. Pan Willi asked me in German, so Radomsky could hear. “Why haven’t you made up a fence?” and pointed to the ravine.

I answered that nobody had told me to make a fence. Then Willi smacked me in the face so hard, that I saw double. He was trying to get himself out of trouble about the fence. The fence was made, that evening he came to my barracks with a bottle of vodka, cigarettes and bread.

One time after the workers who were brought from the Syrets camp every day were brought in, Mishka, the sailor and the lieutenant told us that they had heard a rumour that a group of naked Jews, they did not know where from, had been brought to our camp in the gasenwagen. They were let out on the camp grounds and the Germans mocked them.

They were told to wash themselves and take nettles to rub each other with, so it could be seen that they have been cleaned. They were beaten with whips, sticks or the butts of rifles. Some of them were even beaten to death. Those who were left alive were gathered into a circle and made to sing and dance while being whipped, entertaining their executioners. The entire operation was performed without participation of Germans, only by policemen and camp authorities.

There were many bandits like Grigoryan, Moros, Serbin, Boyarsky and others who thought they had ended up in the camp because of the Jews and that the Jews should be annihilated to the last man. Some days later a gasenwagen rolled into the yard, we thought that it came to transport the workers who worked with us; I was in Budnik’s working place. The door opened, the policeman came in and yelled, “Hands Up”

I tried to take my jacket but they warned us not to touch anything or else they would shoot. We went out into the street where the van was. Vilkes and Ostrovsky were already there. Podikaminer was behind the shed when he noticed that Vilkes and Ostrovsky were being led by the Germans.

He went down toward the ravine and ran away, we stood for a long time while they searched for Podikaminer, then finally they opened the door and ordered us to get in. We didn’t see who else was in there since the door was immediately closed behind us. We were pressed next to each other and started moving.

We couldn’t see anything in the dark, we were saying goodbye to each other thinking that it was the end, I could hear my heart beating and temples pulsating, we all believed that this was the end. We were riding for a long time until the van finally stopped, they did not open the door for a while so we thought that they would start with the gas and that’s why they were spending so much time on it.

Part 3 – Syrets Camp

At last the door finally opened, we did not know if it was Babi Yar, we thought they were going to kill us. It was nearly completely dark outside but one could still see. Some distance away from the van some people were standing and talking to the master who rode in the front of the truck that brought us. Each person had something in his hand, either a stick or a whip.

It turned out that the gasenwagen came late because they had been searching for Podkaminer, we all remained standing, the commandant himself came to our group, we later found out his name was Anton. He was a Czech by nationality; we never learned why he was originally sentenced to the camps.

We learned that he was the highest ranking Sotnyk in the camp; he said something to us in broken Russian and then cursed in Russian well. Then another man approached and said; “Lets get acquainted my name is Rotislav, I think you will remember me, I see that you are cold, now you will get warm.”

In fact, along with the rapid beating of my heart, I was trembling; I don’t know whether it was because of the cold or simply raw fear but my teeth rattled. He yelled out the command, “Attention! Forward, march! Then Run!”

The drilling area was big, when we reached the other end, he ordered us back, when we ran past the place he was standing, he whipped everybody on the head. It is impossible to forget such things, we had been running for about half an hour when he finally gave the command to lie down and rest. But at the same moment he again ordered us up and made us start running again.

He was in a hurry to go somewhere so he said goodbye to us and promised that he would drill us again. He showed us the Jewish barracks where we would live. By the time we entered the barracks we were completely soaked as if we had showered in our clothes.

In the dug-out there were bunk beds for us. People were lying around, some were dirty, others were bandaged up with rags, another was crying a group in the corner was talking. Nobody addressed us, nor even looked at us. We asked who was the leader in the barracks, everybody pointed towards one man, he saw that we were newcomers to the camp and asked us where we were from.

When he learned that we came from 48 Melnikova, he said that everything was clear, he had been waiting for us and already knew everything about us; “You are the ones who sent us bread, I am Ivanov Arkadiy or simply Arkadiy.”

We saw the men who were called punies, they were all very sick, he told us what different shops there were: carpentry, fitting, blacksmiths and electrical. We already knew that the heads of the Jewish work teams, Matkobog and Serbin were complete monsters and they would easily kill a man without a thought.

It was not necessary to get dressed since everybody slept with their clothes on, we all ran out quickly to the line. We newcomers were ordered to stand at the end. Every group knew its place and the masters and Sotnyks gave commands for the morning exercises. We also did what everyone was doing, after the exercises we went back to the barracks to wash and take care of personal needs. We had a total of ten minutes then again we got in line and marched while singing to the canteen.

Everyone got a slice of bread and spoon of coffee in a pot or a can we had to eat while marching and to continue singing all the way to the drill grounds. There the Sotnyks reported to Anton what accidents took place that night and how many people got ill or died. Anton listened to the reports and then gave orders.

For the few Sotnyks that were assigned to work in the city, trucks came to take them and the policemen who went together with them; Anton would give the final command and everybody went to their workplaces Only the camp bosses remained, that day we also remained since we didn’t know where to go. Then Anton cried out something to the master of the Jewish team Matkobog, he ran up to us and started beating us with a stick, we were running towards the exit and he was running after us, beating us on the head. He hit us so hard that we were crying.

At this moment the assistant of the camp chief Pan Yan whom we knew well from 48 Melnikova put an end to it. I asked Pan Yan if we were assigned to the Jewish team for work. He told me that I will work in the carpenters shop, Budnyk will go to the electric shop and Ostrovsky, Mytslmacher will go to the sawing shop. He said something to Vikles but the later did not understand it so he went with the regular team.

In the shop, it was light, warm and clean. Arkadiy showed me my working place, gave me work to do and tools to work with. Here I met Mamayew and Ivanov, who worked not far from me. It was obvious that they were nice people. They told us about themselves, that they were military men but got surrounded and could not escape. They were arrested as communists and brought to the Syrets camp.

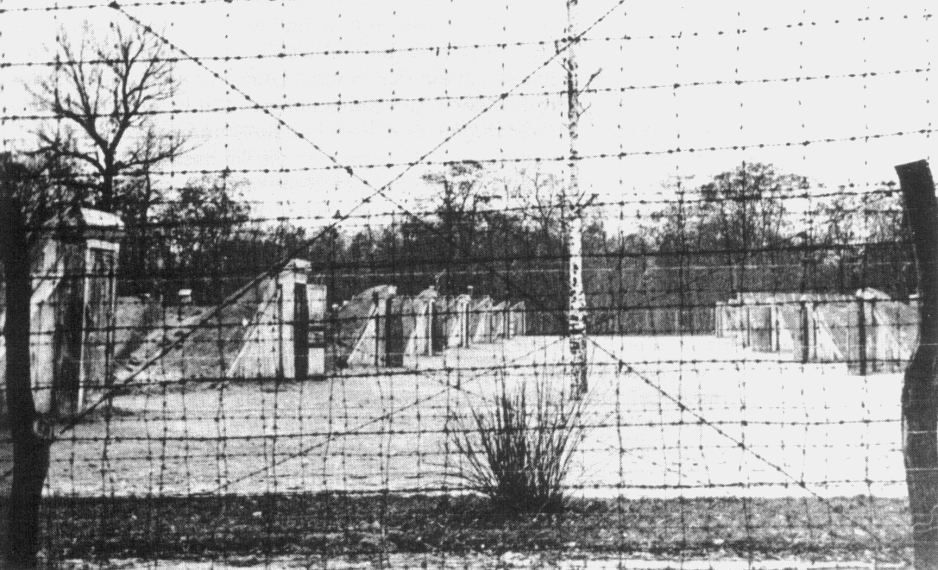

The camp was a vast territory encircled with three rows of barbed wire the middle row was under a high tension current. At the entrance to the camp on the left a big wooden building for guards called a wachstube. At the corners of the camp there were high watch towers with policemen with machine-guns

Inside the camp there was a fenced-in women’s camp, then there was a barren zone and finally our barracks which stood in two rows. The first barrack at the entrance to the zone was a Jewish one. Near our dug-out they had erected a scaffold for hanging people

On the day of our arrival they hung a prisoner who had attempted to run away. Further on there was a long row of barracks and each had its special name, either Soviet, or Partisan, or Communist. On the left side there were odd-numbered buildings starting with 3. There lived the bosses Anton, Rositslav, Boyarsky and some of the other Sotnyks.

Behind that stood the barracks of the masters and after it another one for criminals, tramps and others, the last barracks was a medical building and hospital. Behind the dug-outs there was a small ground where we organised a kind of a market in the evenings. Everything was traded: bread was exchanged for some spoons of gruel, a little bit of tobacco, or for shoes or a shirt or something else.

Further on there was a wooden house that looked like a store house for sanitary cleansing, there was a boiler for disinfecting, a shower-room with two cabins, a lavatory, though without sewage system. Water in the shower-room was always cold and we were made to strip and wash while being whipped. .

The hardest work was under Serbin and Matkobog in the Jewish team, in the camp leather workers made harness for horses, the masters made them also make whips, iron nuts were sewn inside the whips and the masters tested them out on people.

The work of the Jewish team was to dig up dirt from one place and carry it to another. Some were digging and loading earth on to the stretchers while others were running with the stretchers. Chasing after them at all times were the masters with their whips. If someone couldn’t bear the tempo and fell, he would never have any chance to rise again. Every day about 5 to 6 people did not come back from work. The Gestapo brought new ones to replace those who died.

Sturmbannfuhrer Radomsky would often come to the camp in his car carrying himself and his enormous German shepherd Rex by his side, behind him sat the interpreter, a Volksdeutsche named Rein. The word about his arrival would travel across the camp very quickly. Everybody trembled.

The policemen stood at attention hoping he would not find fault with anything, the first to report to him was a Rottenfuhrer on duty, then Anton. They took him around the camp. Sometimes this tour lasted till dinner, but if they had not liked how we sang or marched to dinner, he would make us march and sing instead of dinner.

Usually, we sang, “Oh you Galya” or “Nightingale, nightingale you birdie” or some other song like that. After that the entire camp was lined up and then they would give out punishments according to the seriousness of the incident. A special table was made in the centre of the grounds for whipping people, the prisoner who was to be punished was ordered to take off his trousers and to lie down on the table. His neck and the feet were then affixed with boards so that he could not move.

The strongest men were chosen from the line and ordered to give as many blows as were prescribed. They would beat the other prisoner so hard that his flesh splashed around. Those who did not hit hard enough were then themselves tied to the table and beaten by the others, many times the person could not get up afterwards and Radomsky would shoot him on the spot.

After several days at the camp, I was told that Rottenfuhrer Rider and somebody else had arrived on horse; I looked out the window and saw our boss from 48 Melnikova, Rottenfuhrer Pan George. I came out and asked him if our clothes could be sent over to us, since we only had shirts. Pan George said that he was doing everything to get us back, if it were not for Podkaminer’s escape we would be back there already.

Podkaminer had been caught and would soon be brought here, in the evening Podkaminer was thrown into our barracks: he could not even walk after they beat him and could hardly tell us how it all happened. After running away, he went to Turgenevskaya street where the head of the tailors shop lived. When Podkaminer ran to him, he said that he would help. He fed Podkaminer, let him wash, gave him clean underwear and left for the night.

In the morning he told Podkaminer not to go out because it was dangerous and he would go himself to arrange everything, instead he went to 48 Melnikova and informed that Podikaminer was with him. The Germans sent over two SS soldiers and two policemen. Podikaminer was caught and brought to Gestapo headquarters at 33 Korolenko, he was beaten there and brought to us.

That evening Boyarsky and Matkobog ran to our barracks, whenever Matkobog came to us, something he did often since he was the master of the Jewish work team, he would cry out, Jews I’m your God.

Boyarsky caught Podkaminer and Matkobog started beating him on the back with an iron-rod so hard that we thought they killed him. When they went away Podkaminer lay without any signs of life. In the morning they arrived to take him, I felt very sorry for him when he had to go sit in a car but couldn’t get up, so Budnik and I helped him.

After that when we were at work I saw something that is impossible to forget, at first we saw something that looked like a carriage moving along the road, but we couldn’t guess what was harnessed to it. Then I saw that there were people harnessed to the carriage but with strange long and painted heads.

When they approached I saw that they were Jewish women and that they were carrying sod. Behind them many women were walking in a column singing, “Lemons, you are growing on Sarah’s balcony.”

On one side of this column a Russian woman was walking with a whip in her hand, later I got to know her name, Logvina, she was a master. All women from this team had their hair cropped close, they were half naked and their thighs were covered with rags, their backs and faces were coloured with whip slashes in rainbow colours. The breasts were hanging like empty sacks, their faces and arms were covered with mud, I was told that they cleaned the toilets in the yard and did other dirty work.

Their master, a young and healthy woman, was Anton’s mistress; he gave her a whip with which she beat the prisoners. She called them chaikas, chaika being a Jewish name, and humiliated them as she liked. Many of them could not stand the torture and the hunger and died. Whenever they brought new Jewish women to the camp they replenished Logvina’s team.

Prisoners often ran away from the teams that worked outside the camp despite how thoroughly the policemen watched over them, the punishment depended on the mood of Radomsky. One time he ordered the camp to line up and they shot every tenth man in the line, some of the prisoners pleaded and requested but they pulled them out and continued on. Then all the chosen were brought to the centre of the ground and ordered to kneel. The policemen shot each one of them in the back of the head.

At the shop I learned to make cigarette-cases, there were enough customers, the policemen came, they already knew the price and bought a case for a half loaf of bread and a pack of tobacco. Once Rottenfuhrer Rider came into the shop and turned to me. He told me that I made the cigarette-cases and he asked me to make one for him. I told him that it would be ready in a few days. He drew his initials and asked to put them on the lid of the cigarette-case. I did that also.

Once the assistant of Anton, Rostislav ran into our shop and told our master that big bosses from the Gestapo had arrived and would make a round about the camp, so it was necessary to keep everything in order. After some time they came into our shop and when they stood not far from me Radomsky came up to me and addressed in German for Rein to translate even though I understood quite well.

He ordered me to make a cigarette-case like the one I made for Rider, he didn’t even look at me, then he turned and went away. I was afraid to ask what material to use and about the side. When they went away I told Arkady Ivanov that since Lenya Khorosh could make the boxes better than me, it would be better if he did it. But Lenya got scared and refused to, Ivanov only shrugged his shoulders.

Some time passed, then suddenly one day Radomsky entered the shop and asked if I had made the box. I said that did not know the size and the material, he struck me in the face so hard that blood ran all over my face.

He said that in three days everything should be ready, and they went away, Ivanov went to Anton and settled with him and that I was to escorted to the kitchen to choose bones I required. I chose good bones, boiled them well, cut them into thin plates and made a beautiful table-box for cigars. I wrapped it in paper and handed it over to Rein for Radomsky, later Radomsky came into the shop, he didn’t look at me, but threw a pack of cigarettes on my bench.

On the next day it was raining again, about a hundred partisans were brought in the gasenwagen, they always took them straight to Babi Yar, but this time they brought them to the camp for us to see. They were ordered to kneel with their hands back and the policemen stood behind them. Suddenly one of the policemen cried that he would not shoot, he saw his brother among the partisans.

Then Radomsky pulled out his pistol and almost shot that policeman, the policeman got scared and shot his brother with an automatic gun, then he fell sick on the spot and he was carried away I learned that among the prisoners were traitors, we had been told about it when we were brought to the camp. One had to know with whom to talk, I was shown one informer who worked in our shop. His name was Miroshnichenko, I knew him and was on good terms with him. He worked with Volodya Kotlyar from our barracks not far from me.

Volodya told me that Miroshnichenko changed barracks very often: he would live in one, then in another and then would be transferred to yet another. He used to very quietly and unobtrusively listen to who was talking about something.

Suddenly we found that a car from the Gestapo came and took Zhora the barber away, a fight started in the barracks. People from other barracks began coming into ours and talking secretly to Arkady and Talalayevsky. I came up to Arkady and asked what it was all about but he did not answer. Some days later Zhora was brought to the camp again, he chose the moment when there was nobody in the barracks and cut Miroshnichenko’s throat with a razor.

On the same evening bosses from the Gestapo arrived and announced that not far from our territory a cottage for a general was being built and some specialists were required. The prisoners whose names were called would go there, they read the list of about twelve names.

From our barracks about 8 people were called and Ivanov was appointed the master; all of them were ordered to board the truck that was already waiting. They wanted to take some things, but they were told it was not necessary, as they would be given everything there. Half an hour later we heard some shooting in Babi Yar and guessed what it was our camp was just opposite Babi Yar and we always heard when they were shooting there.

We continued to work as before, some people were killed, others were brought instead, there were rumours all around the camp that our troops came very close to the left bank of the Dnieper. One day the Gestapo arrived and started calling people’s names, all those who were called were sent to Germany. Those who were not called were the prisoners of our Jewish barracks and a few others who were considered especially dangerous, mainly partisans and communists. Out of those who remained, 100 people were chosen, lined up and ordered to march whilst singing.

For the first time the gates were open for them and they went to Babi Yar, the rest of us were ordered to dismantle the machines and pack them into boxes. Some days later we also were lined up and sent to Babi Yar.

Sources: The Thorny Road by Yakov Kaper Photographs and Map of Kiev from the Chris Webb Archive and other private collections

Copyright Chris Webb H.E.A.R.T 2010

|