Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| ||||||||||

The story of Max Block (Part 2)

(no grammatical corrections were made to the original text)

AuschwitzOn October 12th, 1944 Max Block is deported on the seventh autumn transport "Eq“ to Auschwitz, where he is murdered – probably on October 14th, shortly after selection. He had reached the age of 54 years.

Few people were able to report about this transportation; one of them is Frank Bright (Brichta) from Berlin, who is forced to go to Auschwitz at the age of 16 years together with his mother:

We were on the list of transport “Eq”. [...] On 12 October 1944 we boarded a third class railway carriage, similar to that which had brought us from Prague to Theresienstadt 15 months ago. [...]

We sat on long wooden, slatted varnished, curved seats[...].

Decidedly more comfortable than the pitch dark cattle truck which normally entered and left the ghetto with frightened human freight. Why we were so privileged I don’t know. [...]

The simple answer, without recourse to any conspiracy theory, is that the Reichsbahn just happen to have this particular train available for one of their very many journeys to this particular destination. [...]

Although there was a large window there was nothing to see. We were into October and it gets dark early in those parts. There was the rhythmic clanging of steel wheels against the joints between the steel rails. We were on our way. [...]

Day dawned. We were passing through a dull, flat landscape. And then the train slowed down and all of a sudden we were in a large area defined by concrete posts, wire and wooded towers in the distance. [...] The train came to a halt, the seal on the door was removed, we were ordered out. Others remember the shouting, screaming, threats, whips being brandished, snarling dogs. Nothing like that occurred at the arrival of our transport, there was no need to. [...] In the melee of leaving the train and being put into one of the two columns I became separated from my mother. Anyway, my mother was in the column to the left of mine. [...] Her column went forward first, one at a time until one came across an SS-officer with several assistants either side of him. I couldn’t see exactly what was happening but some of us went to the left and some to the right. I had seen my mother go to the left.

It didn’t seem to take all that long for the left column of women to be processed and then it was our turn. I was, as I said, near the front and when it was my turn I walked forward until I got to the SS-officer in charge. According to the accounts of others he would look at one, just for a second, the process was quite quick, and indicate with his finger where the person in front of him was to turn. I can’t remember any of that, I didn’t take that in. I had seen my mother go to the left and so I simply turned left too. I was called back. Obviously the officer’s assistant had watched his finger and saw it point to the right even if I had not. So I was called back and told to go to the right. [...] On the right I waited for further directions with the others who had also been told to turn right. There weren’t many of us. From records I now know that out of our transport of 1,500 who left the ghetto of Theresienstadt on 12 October 1944 only 78 survived. Of course, a few more may have survived this first selection and died, or were put to death, later but there were very few anyway. Say that there were 90 picked to work [...]“.33 Max Block is not among them; he is not registered as a prisoner but is sent to the left side, directly to the gas chamber. Max‘ age alone is a sufficient reason for this; selection was very rigorous in October 1944. 34 Just two weeks later, killings are stopped in Auschwitz gas chambers for ever. The (Calendarium of events in the concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau 1939-1945): Contains ten entries for October 14, 1944, including the following: „With a RSHA** transport, 1,500 Jewish men, women and children from Theresienstadt ghetto arrive. Young and healthy men and women are sent to the transit camp and the remaining people are killed in the gas chambers [...] 3,000 Jewish men, women and children are killed in the gas chambers of Crematorium III. Among those killed people are Jews from Theresienstadt, selected at the ramp.“ 35

From a report by Jewish pathologist Miklós Nyiszli who had to work for the infamous SS doctor Mengele* from July to November 1944 in Crematorium I: „It’s early in the morning. From the ramp, the long whistle of a railway engine is heard. I go to the window where I have a good sight of the ramp. A long train is standing there. [...] Lining up and selection takes hardly half an hour. The left group moves slowly. [...] After five to six minutes, the transport reaches the gate which opens widely. In the usual rows of five they take the turn to the yard. No one of the marchers will ever be able to report on what follows next. [...] They move on, about 100 meters on a path lined up by green lawn, leading to a grey metal grid. Ten concrete steps lead to a subterranean hall. At the entrance a sign announces in German, French, Greek, Hungarian language that this was a bath and disinfection room. The unsuspecting calm themselves, even the doubtful. They descend the steps nearly light-hearted. They enter a hall which is about 200 metres long, brightly illuminated and whitewashed. A row of columns stretches along the middle of the room. Around them and along the walls there are benches with long rows of coat hooks above them, marked with numbers. By big notice boards, people are instructed to bind their shoes and clothes and to put them on a hook. It is stressed that everybody has to remember the number of the hook in order to avoid unnecessary tumult upon return from the bath. [...] SS soldiers appear and give the order: ‚Undress everything!‘ [...] The SS make their way through the crowded room towards an oak door at the end of the hall. The naked people are pushed to the next hall which is also brightly illuminated. It is very similar to the first hall, except that there are no benches and hooks. In the middle there are four columns with a 30 metres interval between them, reaching from the floor to the ceiling. These are no supporting pillars but quadrangular pipes made of steel plates containing holes like a sieve. Now all victims are in the hall. A loud order: ‚SS and special commando leave the room!‘ These persons take the exit and count each other. Doors are slam shut and lights are extinguished from outside. In between, a luxury pickup from the Red Cross approaches the building slowly.

A SS officer and a medical orderly get out. The latter carries in his arms four green tins. [...] He pours the contents– a lilac substance consisting of bean-sized grains – from the tins into an inlet leading to the steel pipes within the subterranean gas chambers. The substance: Zyklon B. In contact with air, a gas develops from this substance and penetrates through the thousands of holes in the pipes to the hall stuffed with human beings. Thus the whole transport is killed within five minutes. The Red Cross car appears whenever a transport arrives. The containers with the deadly substance are always brought along from outside – never is there a stock within the Crematorium. What a cunning precaution! But is it not even more perfidious to have the poison transported by a car carrying the Red Cross? The gas hangmen wait another five minutes before they are quite sure of their cause. The light a cigarette, then they get on the car. They have just killed 3,000 completely innocent people.“ 36 There is a short report on the death of Dr. Siegfried Wolff, a pediatrician from Eisenach, Germany, who has to flee to Holland just as Max Block, and is also deported to Theresienstadt, where he cares for orphan children. When they are sent to Transport Eq, he refuses to abandon them and joins them voluntarily on their last journey: "A fellow prisoner in Auschwitz, who was a lawyer in England after the war, reports how he had to watch the gassing of Dr. Wolff and his children through a pane. Gasping for breath and in mortal agony, they pressed themselves firmly to their keeper and died, clinging to him tightly.“ 37 Then the most dreadful work of the Special Command begins. The corpses have to be separated from each other, must be cleaned and dragged to the lift which carries them to the cremation room. Their hair gets cut off and all their gold teeth are removed, before they are burnt to ashes within 20 minutes. Vans carry the heaps of ashes from the Crematorium yard to the nearby Vistula River and discharge them into the water. 38

It was only a few years ago that a former member of the Special Command was capable of describing the horrible work that he was forced to do in Autumn 1944 in Crematorium III: "I never told anyone about this until now. It is so depressing and sad that it is hard for me to talk about these images of the gas chamber. Some victim’s eyes had protruded from their orbit, so much overstrained was their organism. Others had blood everywhere or were soiled with their own or other victim’s excrements. Dread and the impact of the gas often made the victims to empty their body from everything that was inside. Some corpses were very red, others completely pale, every dying body had reacted in a different way. But all suffered in their death. People often think that the gas was simply thrown inside and people just died. But how they died!... We found them clinging to each other, everyone had gasped for air in despair. There was an acid emerging from the gas thrown to the ground, it rose from the ground to the ceiling, and everybody longed for air. even if they had to climb on each other for that. They did it until the last person died. [...] What we saw after opening the door was so unspeakable cruel, you can not imagine what it looked like." 39 Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp has become the most impressive symbol of the holocaust, the industrial genocide committed by the Nazis. The camp Auschwitz II (Birkenau) is constructed during the last months of 1941 by prisoners of the Main camp Auschwitz I, which was in operation since June 1940. Mass deportations to Birkenau start in spring 1942. More than 900,000 Jews are killed in the gas chambers shortly after arrival; one of them is Max. Another 400,000 prisoners are reiterated upon arrival; more than half of them die due to inhuman living and working conditions and due to the terror by the SS forces. Auschwitz is liberated by the Red Army on January 27, 1945. By decision of the United Nations of 2005, International Holocaust Memorial Day is celebrated on this date. * Short profiles of the Nazi criminals mentioned above: SS-Hauptsturmführer Anton Burger, born 1911 in Neunkirchen/Austria. Dreaded for his brutality, he is Commander in Theresienstadt from July 1943 until February 1944. Before and after this period, he is one of Eichmann's close coworkers and organises deportations of Greek and Hungarian Jews. After the war, he is sentenced to death in absentia in Czechoslovakia, gets arrested twice in Austria but manages to escape. He lives partly in Austria, under an assumed name, and runs a mountain hut in 1960/61, the Mandlwandhaus near Salzburg. He gets to know a right-wing industrialist from Essen who provides him with documents, work, and housing. Burger dies in Essen in 1991. [Miroslav Kárný, Raimund Kemper, Margita Kárná. Theresienstädter Studien und Dokumente. Prag 1995, p.241ff] SS-Obersturmbannführer Karl Adolf Eichmann, born 1906 in Solingen/Germany. Chief of „Jewish department“ IV B 4 in „Reichssicherheitshauptamt“** during World War II. From his Berlin office situated in Kurfürstenstr. 115/16, he organises the deportation and assassination of the European Jewry. After1945, Eichmann flees to Argentinia. He gets detected by a former KZ prisoner and kidnapped to Israel, where he is sentenced to death in 1961 and executed in 1962. SS-Sturmbannführer Ferdinand aus der Fünten, born 1909 in Mülheim/Ruhr, Germany. As the chief of „Central office for Jewish emigration“ in Amsterdam, he organises registration and arrest of Jews in the Netherlands. In 1950 he is sentenced first to death, then to life-long imprisonment. He dies 1989 shortly after release from prison.

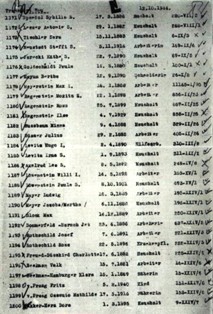

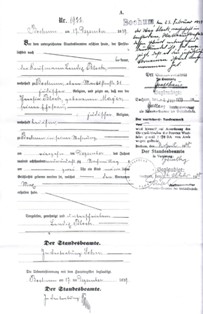

SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Günther, born 1910 in Erfurt/Germany geboren. As the chief of „Central office for Jewish emigration“ in Prague, he is responsible for deportations of Jews from the occupied Czechoslovakia, the „Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren“, from 1939-45. Tall, good-looking and polite, he is known as „the smiling hangman“ in Theresienstadt. Günther dies in May 1945 whilst attempting to resist being arrested in Czechoslovakia. SS-Hauptsturmführer Dr. med. Dr. phil. Josef Mengele, born 1911 in Günzburg/Germany. After studying medicine and anthropology, he graduates at the Frankfurt „University institute for genetic biology and racial hygiene“. From 1943-45 responsible for innumerable „selections“ and for barbarous medical experiments and assassinations in Auschwitz. After internment in1945, he is released unrecognized and hides in the Upper Bavarian village Mangolding near Rosenheim under an assumed name. 1949 he flees to Argentina, after Eichmann‘s discovery he rushes on to Paraguay and Brazil, where he dies in 1979 during a bath in the sea. [Lucette Matalon Lagnado, Sheila Cohn Dekel: Children of the flames. Dr. Josef Mengele and the untold story of the Twins of Auschwitz. New York 1991) SS-Obersturmführer Karl Rahm, born 1907 in Klosterneuburg/Austria. Since 1939 dealing with Jews‘ deportations firstly in Vienna under Eichmann, then in Prague under Günther. Rahm is camp commandant in Theresienstadt from February 1944 until the camp’s liberation in May 1945. He flees to Austria at the end of the war, gets arrested and extradited to Czechoslovakia, where he is sentenced to death and executed in 1947. ** RSHA: "Reichssicherheitshauptamt“, SS office in Berlin, responsible for the organisation of deportations Securing of evidence Today appeared before the undersigned registrar the personally known merchant Bendix Block, resident of Bochum, Obere Marktstraße 21, of Jewish confession, and declared that his wife , Theresia Block, née Mayer, of Jewish confession, living with him, gave birth to a male infant in his habitation in Bochum, on the fourteenth of December of the year 1889 at two o'clock p.m., who was given the name Max “ Marginal note: Bochum, February 23rd, 1939 Max Block, living in Amsterdam, Watteaustraße 21, whose birth is certified here, has announced that he took the additional name Israel.“ The marginal note above is hereby deleted ex officio by order of the Upper President of the province Westfalia, according to §134 DA. Bochum, April 7th, 1948“ Since 2007 I researched my family’s history. My mother comes from a Jewish family in Munich; due to early anti-Semitic agitation they left Munich in 1929 and Germany in 1934. My grandmother Herta Walter, Max Block’s sister, survived the Nazi era in France and Switzerland, her daughters in Denmark and Great Britain. After the war they returned to Germany where I was born in 1960. They did not talk much about their experiences during the war nor about our relatives‘ fate. At least I got the most important point about my great uncle Max Block’s fate: Auschwitz. My aunt wrote: „Some time during the Nazi era he emigrated to the Netherlands, where he still lived when the Germans invaded the country. Max is the only one of the siblings who was dragged to a concentration camp and killed by the Nazis.“ 40 I did not demand more information then. But now it is important to me to collect and publish evidence about them and the world’s worst crime: The persecution and assassination of European Jewry.

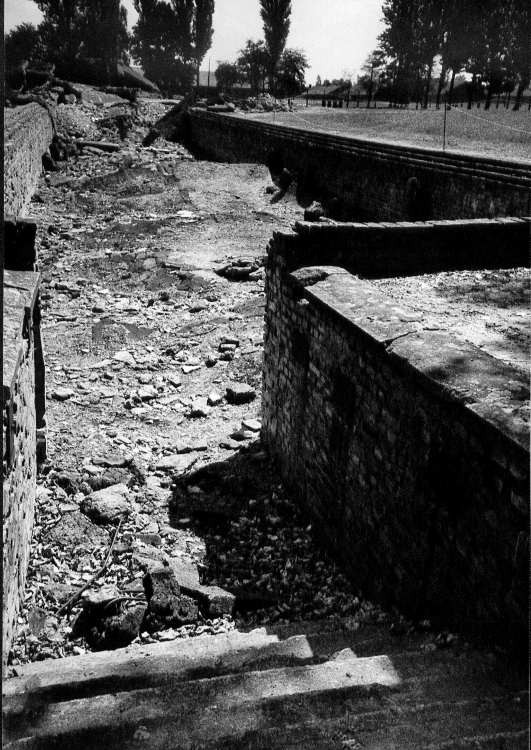

As well as factual reports and documents from archives there are also photographs which I have taken – in color from the places where my relatives lived, in black and white from the places where they suffered. The latter pictures are shot with a Lomo“, a small Russian compact camera with a wide angle (32mm) and high luminous intensity, enabling long exposure times. At night, blurredness and movement artifacts contribute to visualization of the ghastly atmosphere I felt in these places. In May 2008 I visit Theresienstadt and experience the solemn ceremony at the anniversary of liberation. There are speeches by the president of the Czech parliament, by representatives of the veterans and of the churches, there are innumerable funeral wreaths from embassies and memorial sites, there is the Slaves’ Chorus from Nabucco and the kaddish. In the middle of the night, I start my own commemoration. I go to Bauschowitz station by car and walk the three kilometres to Theresienstadt by foot. I take along my Lomo camera and catch the ghastly atmosphere in the plain where once the census took place, in the „Bauschowitzer Kessel“ (encircled area). At midnight I stand in front of Hamburg barracks which served as “Schleuse” for the departing transports in those days. I take a photograph showing remnants of the railway line leading out of the “Ghetto” next to the barracks. This was the way Max Block had to take on October 12th, 1944, leading to Auschwitz. A month later, in June 2008, I go to Auschwitz with a study group. “It wasn’t green here at all“, our interpreter says. “All full of mud and dust, it was a marshland. All grass was trampled down.” We follow the rail lines to the ramp where selection took place. On October 14, 1944, Max Block stood here with 1,500 others. From all I know, it is highly probable that he was sent to the left side, to the gas. An old man accompanied by a younger one approaches us and asks in broken German: „Was here selection?” Yes. – „I was here, Jews’ transport from Hungary, only stayed a few weeks, maybe six, than further on to Dachau. That’s why I have no number”, he says and shows his unscathed forearms. He was liberated in a small camp in 1945 and went to Israel. It is his first visit to Auschwitz since, and he wants to show his son everything. In 1944, he was sent to the right to pass through one of the wooden gates wrapped with barbed wire, many of which connected the different parts of the camp fenced with barbed wire under high voltage.

We take the other direction now, to one of the blasted and decayed buildings which were very similar to each other and consisted of an undressing hall, a gas chamber and a Crematorium each. Behind it we see a former pond where the ashes from the crematories were poured. The remnants of those killed are everywhere in this place: “The little white pieces on the ground are skeletal remains”, our interpreter tells us. A few dry roses lie on the steps leading down to the undressing hall. Suddenly something happens that impresses me even deeper: The old Jew sings the Kaddish with a marvelous voice, then his son repeats the song. I return to Birkenau at night to take photographs. The gate we took to exit the extermination camp is still open. The sky above the barracks is pale reddish, a thunderstorm seems imminent. Again I follow the railroad tracks. Light rain falls down. Two little grave lights mark the point where selection took place on the ramp. I take photographs. There is also a candle near Crematorium III, sheltered from the wind by some bricks. I have brought along a small bunch of roses which I put down in front of the gas chamber. At this moment the tension inside me resolves, I feel only calmness and grief. Carefully I walk around the destroyed Crematorium and get to the black pond. The full moon shines on it and makes it appear even more blackish. I look up at the sky high above the poplars. You have got a grave in the clouds…***

This report on Auschwitz is part of an article which I published in "Mitteilungsblatt der Lagergemeinschaft Auschwitz“ (Nr. 2/2008, p. 8ff). The line “You have got a grave in the clouds” is adapted from the famous poem “Todesfuge” (“Death Fugue”) by Paul Celan. A friend asks me two years later what my great-uncle actually would have said about my search for evidence, if this was possible. „Max might probably say that I’m meschugge, just crazy to spend so much time with that old stuff. And I could answer: ‘I realised that you are important too for me, Max, and with all my heart I want to make sure that your fate won’t be forgotten.’ And he would shrug and smile.” And I realised that the burden I carry with me „since ever“ – the history of my family’s persecution – has become less heavy since I can look at it more closely.

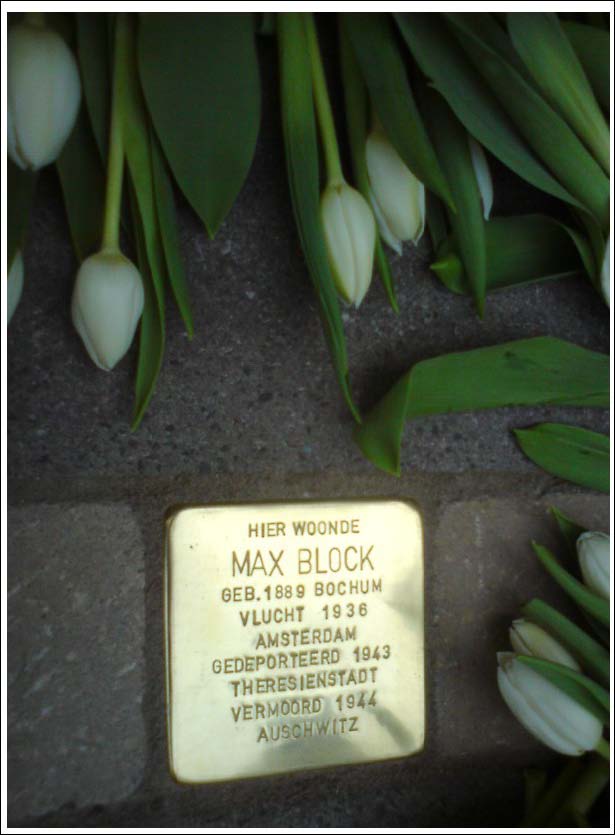

Though very painful at times, this “securing of evidence” is helpful for me, it is my way of coping. I want to thank everybody who helped me in my search and who stand up against oblivion and indifference. The French Auschwitz survivor and former president of the European Parliament, Simone Veil, states in her preface to Shlomo Venezia's book: „That he, just as me and many others, told his story with such a delay, had the reason that nobody wanted to listen. We returned from a world where we were expelled from mankind: We wanted to report it but we encountered lack of understanding, indifference, and even hostility from others. It took us many years after deportation to take the courage to talk, because finally people did listen to our stories." 41 Today there are more and more people who listen and demand for more information, also in Germany. Many survivors have told their stories and touched the hearts of their audience directly. This makes me happy. But there is only little time left in which witnesses can present their testimonies themselves. And so I hope that also stories told by others, like mine about Max Block, will reach many people and help to make sure that crimes like those in Auschwitz can never happen again, that we shall have the power and the courage, both in everyday life and in the education of our children, to take a stand against intolerance and violence. To my opinion, the „Stolpersteine“ (stumble stones) of Cologne artist Gunter Demnig have a tremendous effect to achieve this goal. More than 22,000 of these memorial stones have been placed in more than five hundred municipalities in Germany and several European countries. The artist writes: “Stolpersteine are 10 cm concrete cubes furnished with a brass plate and set into public sidewalks in such a way that no one can come to harm by them. And nevertheless they are called stumble-stones, for those who see them in passing should stumble in their spirit, pause briefly, and read the inscription. A piece of history is thus brought into our everyday lives directly in front of the victim’s dwelling, under the heading ‘here lived …’ Stolpersteine are intended as tokens of memory, to bring the victims out of their anonymity in the place where they lived.” 42 Since April 28, 2011, there is a stumble stone in front of Brahmsstraat 11 in Amsterdam, in memory of Max Βlock. -Thomas Nowotny Dr. med. Thomas Nowotny Kinder- und Jugendarzt Allergologie Naturheilverfahren Salzburger Str. 27 D 83071 Stephanskirchen Tel.: ++49 / 8031 / 3918018 Fax: ++49 / 8031 / 3918019

Sources: Digitaal Monument Joodse Gemeenschap in Nederland, http://www.joodsmonument.nl/ Gedenkbuch der Opfer der Verfolgung der Juden unter der nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft in Deutschland 1933 – 1945. Bundesarchiv, Stand 1/2011, http://www.bundesarchiv.de/gedenkbuch 1 Nora Walter: Unsere Familie (unpublished, 1990) 2 Berliner Adressbücher 1925-43, unter Benutzung amtlicher Quellen. - Berlin: Scherl 1896-1943 Zentral und Landesbibliothek Berlin, http://adressbuch.zlb.de/ 3 Nora Walter: Unsere Familie 4 Nora Walter: Schilderung des Verfolgungsvorgangs (1955) 5 Staatsarchiv Potsdam, Pr.Br.Rep. 36A, Oberfinanzpräsident – Devisenstelle – A 392 6 Archiefkaart Erich Block, Stadtarchiv Amsterdam 7 Archiefkaart Max Block, Stadtarchiv Amsterdam 8 Anna Hájková: Die Juden aus den Niederlanden in Theresienstadt. Theresienstädter Studien und Dokumente 9/2002; p.138 9 Veit Schmiedinger, Wilfried Schoeller: Transit Amsterdam. Deutsche Künstler im Exil 1933-1945. München 2007 10 Archiefkaart Max Block, Stadtarchiv Amsterdam 11 Ben Barkow, Raphael Gross, Michael Lenarz (Hg). Novemberpogrom 1938. Die Augenzeugenberichte der Wiener Library, London. Frankfurt/M 2008, p.159f 12 Archiefkaart Max Block, Stadtarchiv Amsterdam 13 Anna Hájková: Die Juden aus den Niederlanden in Theresienstadt 14 Anna Hájková: Die Juden aus den Niederlanden in Theresienstadt 15 Anna Hájková: Die acht Transporte aus dem Reichskommissariat Niederlande nach Theresienstadt. Theresienstädter Studien und Dokumente 2001 16 Personal note by Peter Kruit MA, Nederlandse Rode Kruis, Den Haag, vom 18.8.2009 17 Jacob Presser: Ashes in the Wind. The Destruction of Dutch Jewry. London 1968, p.533 18 Else Dormitzer: Drei Berichte über Theresienstadt. Ms. WL. London 1945/46/55. Zit. nach: H.G. Adler: Theresienstadt 1941-1945. Das Antlitz einer Zwangsgemeinschaft. Reprint 2. Aufl. 1960, p.725f. 19 Ludmila Chládková: Ghetto Theresienstadt 20 Resi Weglein: Als Krankenschwester im KZ Theresienstadt. Stuttgart 1988, p. 41f 21 Weglein, p. 55 22 H.G. Adler: Theresienstadt 1941-1945. Das Antlitz einer Zwangsgemeinschaft. Reprint 2. Aufl. 1960, p.161 23 Adler, p. 296 24 Adler, p. 326ff 25 Adler, p. 377f 26 Adler, p. 584ff 27 Federica Spitzer/Ruth Weisz: Theresienstadt. Berlin 1997, p.56ff. 28 Saul Friedländer: Das Dritte Reich und die Juden. München 2008, p 1020 29 Miroslav Kárný, Raimund Kemper, Margita Kárná. Theresienstädter Studien und Dokumente. Prag 1995, p. 7ff 30 Miroslav Kárný, p.18 31 Weglein, p. 68f 32 Adler, p. 41ff 33 The unpublished memoirs of Frank Bright – Selected extracts used with full permission. Dedicated to Hermann and Toni Brichta – Both murdered in Auschwitz. Online version/ Copyright: www.holocaustresearchproject.org 2008. Übers.: T. Nowotny 34 Personal note by Peter Kruit MA, Nederlandse Rode Kruis, Den Haag, vom 18.8.2009 35 Danuta Czech: Kalendarium der Ereignisse im Konzentrationslager Auschwitz-Birkenau 1939-1945. 2. Aufl., Hamburg 2008, p. 906f. 36 Miklós Nyiszli: Im Jenseits der Menschlichkeit. Ein Gerichtsmediziner in Auschwitz. 2. Aufl., Berlin 2005, p.33ff 37 Martin Glauert: Kinderarzt in Auschwitz. Der schwere Weg des Dr. Wolff. Pädiatrie hautnah 12/2001, p. 487 38 Nyiskli, p. 39f 39 Shlomo Venezia: Meine Arbeit im Sonderkommando Auschwitz. 2. Aufl., München 2006, p. 103ff. 40 Nora Walter: Unsere Familie 41 Venezia, p. 15 42 www.stolpersteine.com

Copyright. Thomas Nowotny H.E.A.R.T 2012

|