Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| |||||||||||||||

What it took for one Jewish man to survive the Holocaust The Story of Victor Lewis [Published with the permission of Victor Lewis]

Victor Lewis (Leserkiewicz) was born in Krakow, Poland, in 1919 to a religious Jewish family. At the beginning of World War II, he had two parents, Abraham and Berta; two sisters, Lola and Greta; and two brothers, Leon (Leszek) and Jacob (Kubus). Lola left Krakow for Palestine years before the war broke out and was fortunate to have avoided the Nazi atrocities in Europe.

From the transport out of the Krakow ghetto that should have killed him, to the gruesome concentration camp at Plaszow, and finally, after five years of hardship - to the relative “safe haven” at Oscar Schindler’s ammunition factory in Brinnlitz, Czechoslovakia, this is a heroic account of intense hardships and harrowing near-death experiences that were required for Victor Lewis to survive the Holocaust.

Deportation from Krakow A year and a half after the invasion of Poland by the Germans, the Nazis evacuated the Jews from my home town, Krakow, and resettled us in very cramped quarters in the most dilapidated part of the city. On March 13, 1941, my family of six people was forced to relocate from our comfortable 3-bedroom home at Retjana # 5 to a cramped one bedroom apartment at Targowa # 1, which we shared with several other families.

Life was difficult in the ghetto. Jews were routinely abused, assaulted, and even murdered by the Nazis, who patrolled the streets with pistols, rifles, and whips. We were prisoners at the hands of an abusive force that had prompted a world war, but we were totally unprepared for the obscene horrors and large-scale genocide that our captors were about to execute on us.

The date was October 28, 1942. The Nazis were about to implement their second deportation of Jews from the Krakow ghetto to the extermination camps. We were told that the ghetto would be liquidated, that we all were to be transported to labor camps, and that everybody had to go to Plac Zgody square with their most important belongings.

Fear could be seen on the faces of every Jew in the ghetto. Everyone felt that something horrible was about to happen. On my way to our family’s apartment, I met my parents, my sister Greta, and my brother Leszek inside the corridor of their building. My parents had come out of the bunker where they were hiding, and I wanted to warn them to stay inside.

They didn’t have any working papers (Arbeits-bescheinigungen), so I thought that their lives could be in danger. But, it was too late to tell them to go back into hiding. From all sides, the SS Gestapo appeared before us and pushed us into the street.

Leszek and I had working papers indicating that he was a toolmaker and I was an auto mechanic for the German SS. We thought that these papers would save us and our family from the deportation. We presented the papers to SS Obersturmfuhrer Martin Fellenz, {1} a Gestapo officer who was in charge of the deportation.

Fellenz ripped up our papers, began to beat us with his club, and ordered us to go with all of the other prisoners to Plac Zgody. At Plac Zgody, I noticed many familiar faces, including my girlfriend Regina’s mother, Ida, and her two sisters, Tosia and Gienia.

I wanted to talk to them but I was not permitted to do so. I had to sit on the ground and remain still. The Germans ordered us not to move an inch. To prove their point, they began to kill anyone who got up or moved around. At that point I decided that I had to escape, no matter what might be the consequences.

I told Leszek my plans, and he said he would try to escape, too. I told my parents and sister what I intended to do, and they told me to go ahead and run. Soon, we were ordered to line up, four in a row.

I told my family not to look for me if I tried to escape. Passing Wieliczka Street, I tried to run into a house, but I was unsuccessful. I was stopped by an SS guard and forced back onto the line. I was lucky that guard did not kill me right then and there for trying to escape.

* On October 28, 1942, Zgody square was the site of a roundup of thousands of Jews, random murder of innocent people, and the deportation of all of the people rounded up that day to the extermination camp at Belzec.

Round up and forced onto trains

After marching in silence for an hour, we arrived at the Plaszow Railroad Station where cattle cars were ready to be loaded with Jewish prisoners. We stood in front of the train for a few hours. Then, all of a sudden, the doors from the cattle cars were pulled open.Yelling at us to climb into the cars as quickly as possible, the SS began to beat Jewish men, women, and children with their rifle butts.

Some of us were killed from the beatings and shootings during this torturous mayhem, but most managed to get into the cattle cars. When Leszek and I tried to help our parents into the cattle car, the Nazis demanded that we “hurry up” and began to hit us on our heads with their rifle butts. People were panicking as they were forced into the train. I knew that I had to escape from this situation, no matter what. More than a hundred adults and small children were packed into our small cattle car.

There was no water and very little air to breathe. People were screaming and there were many cries for help. Some of the older and weaker people began to die. Some people began to take off their clothes to get relief from the unbearable heat. My heart was breaking at this horrible scene. I felt that I couldn’t bear the torture any longer. gas chambers! Once more, I told my father that I had to escape! Escape from the Death Train

I managed to occupy a spot on the train near a small window. The window was barricaded with two steel bars. When the train left the station, I pulled a hidden hacksaw blade that I kept in my boot and I started to cut through the bars. Fellow prisoners began to protest loudly, arguing that if anyone would be missing during a recount at our destination point, all remaining prisoners would be killed. I screamed back at them, "Do you really believe that we are going to a work camp? This whole transport is going to the gas chambers, so save your lives!" Most of the prisoners had hoped that they were going to a work camp, not to an extermination camp. It was difficult for them to believe that the Nazis were about to conduct genocide on the Jewish people. By sunset, I completed sawing through the bars. When I asked my parents to jump with me, my father replied: "If you can save yourself, then, by all means, go ahead. But I am too old to run, and mother is too old, too." Then I asked my sister Greta to follow me. She replied, "I will stay with mom and dad. I will watch over them and take care of them." Only Leszek was willing to jump. We both knew that jumping might not be safe. The train was moving fairly fast, so we weren’t sure how we would land after we jumped. Furthermore, the SS soldiers were posted with machine guns on top of each cattle car, ready to gun down anyone trying to escape. Nevertheless, we thought that we would certainly be killed at the extermination camp in Belzec, so there really was no choice. When I was ready to jump, my whole family had tears in their eyes. My father gave me money and his golden Shafhausen pocket watch and chain, and told me to sell the watch if I need the money. Leszek received mother's and sister's jewellery to exchange for cash. At this point, I became very anxious and began to wonder if it was right to leave mom, dad, and Greta under such harrowing circumstances. I wondered if my brother and I could help the family somehow if we stayed. But I was fearful that everyone on the transport was about to experience a barbaric death at the Belzec gas chambers. I felt an uncontrollable urge to jump out of the train. It was a very painful decision to jump, which still haunts me to this day. (After the war, I learned that on the same day that the transport arrived in Belzec, seven thousand Jews from the Krakow ghetto perished in the gas chambers. I never again saw or heard from my parents or sister, or from Regina’s mother and sisters who were also on that same transport. Apparently, they were among the the 600,000 Jews who perished in Belzec.) Once our train reached the forest in Niepolomice, we decided to make our escape. The time had come to say goodbye to my parents and sister. This was the most traumatic moment in my life, knowing that I probably would never see them again. After my last embrace with my parents and sister, Leszek helped me to climb up the window. It was already dark and the train was moving fast. I took a deep breath and jumped into the night. I fell unconscious on the tracks where I laid for several hours. {2} When I awoke early in the morning, it was still dark and I had no conception of where I was. I slowly began to realize what happened to me. I was bruised from the jump but I didn’t pay much attention to my condition. My thoughts were with my parents and sister, and whether Leszek survived the jump. Shortly after I regained consciousness, I got my bearings and began to walk along the railroad tracks towards the village of Klaj, hoping to meet Leszek there. There was no sign of him. Not knowing what to do, I boarded a train to Bochnia, where several of my relatives lived. I thought that maybe he would have gone there for safety. When I arrived in Bochnia, I found our relatives, but there was no sign of Leszek. I became worried about whether he survived the jump from the train.

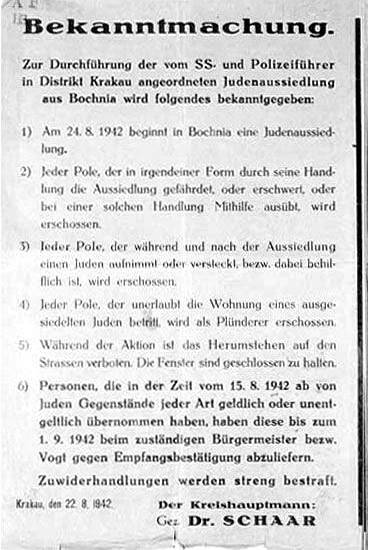

I spent two nights in Bochnia before deciding to go back to the Krakow ghetto to look for my brothers and girlfriend, Regina. I thanked my family for their hospitality and I left them. While walking to the railroad station, I saw a large group of SS special commandos marching towards the Bochnia ghetto where I had just been. Fortunately, they did not question me or suspect that I was Jewish. If they had questioned me, they would have killed me on the spot. Jews had to wear armbands at all times (I was not wearing mine)and we were not allowed on trains. The punishment for either of these crimes was death. Had I stayed with my relatives in Bochnia for just a few minutes longer, I would have been trapped in the Bochnia ghetto and threatened with death. The SS commandos that I saw near the train station were preparing to liquidate the Bochnia ghetto that day and transport thousands of Jews to Belzec—the same concentration camp where I was headed to on the transport with my family the day before. I never again saw my relatives from Bochnia. I wondered whether they were transported that day and met their deaths in Belzec. At this point, I had a horrible sense that most of my immediate family was dead. I felt helpless and alone for the first time in my life. I began to cry from my feelings of desperation. Nevertheless had to move on and look ahead in order to survive. Nowhere to Go (except back to the Krakow Ghetto)

It may seem strange that I had headed back to the Krakow ghetto, the very place where Nazis were transporting thousands of people to their deaths. But, the Krakow ghetto was the only place for me to go. I had no other choice. The cities and villages were occupied by Nazis, and I would have been shot for not having a permit to leave the ghetto.

I didn’t have any connections with underground partisan groups, and I thought that living in the forest was too risky. I went back to the familiar surroundings where I thought I had a chance to survive, even though life in the ghetto was very dangerous. Two days after my arrival, I was overjoyed when Leszek arrived. He survived the jump and he also determined that the Krakow ghetto offered him the greatest chance to survive. Our younger brother, Jacob, also came to the ghetto to look for the family.

He had been placed by our parents in the safety of a gentile family the year before, but when he heard about the mass deportations, he wanted to find out if any of us were still alive. Because he was only fifteen, ghetto life was much too dangerous for Jacob. Leszek and I were able to place him in “Kabel,” a safe factory, with money that our parents gave to us. He was lucky to have worked and lived at Kabel until September 1944. When I came back to the ghetto, I no longer had a "kennkarte" (identification document), since it was taken from me during my deportation to Belzec.

It was very dangerous not to have a Kennkarte. The Nazis ordered us to carry the kennkarte at all times. To ensure my safety, I asked a friend who worked in the labor department to place me with a group of some 150 men, known as the "Barackenbau," who were building the barracks for the new concentration camp at Plaszow. Since Kennkartes were not required for Barackenbau workers, I was lucky to have landed safely again without getting into trouble with the SS – at least for a while. Building Barracks at the Plaszow Concentration Camp

During the first two weeks with the Barackenbaus, I left the Krakow ghetto with a group of fifty men early in the morning and returned back to the ghetto late at night. The walk was quite long, nearly four miles each way. After we had built three barracks, we were placed in one of the barracks and never returned to the Krakow ghetto again. We built the Plaszow concentration camp under horrible conditions, and constantly under the fear of death.

Our daily food ration was just one slice of bread and a cup of dark coffee in the morning, a cup of soup at lunch, and a cup of soup in the evening. This was a meager amount of food for young men after a hard day of physical labor. Many of the men starved to death from hunger. Some were killed when they became weak. If the SS saw anyone not working hard enough, they would shoot the person or whip him with 25 lashes. The only good thing about working in the Barackenbau was the fact that I avoided being in the ghetto during its final bloody liquidation on March 13, 1943.

Several thousand Jewish men, women, and children, including many of my friends and relatives, were massacred on that day. According to all accounts, blood was flowing in the streets of the ghetto like water. Those who survived were transported to Plaszow. Fortunately, Leszek, Regina, and her father, Israel, survived. After five months, it was great to be reunited once again. However, we were about to face the cruel an barbaric realities of life at the Plaszow concentration camp.

Life at Plaszow under Amon Goeth

Plaszow was an extermination camp under the direction of Amon Goeth, the Nazi commander whose treacherous behavior was depicted in the movie, Schindler’s List. Every day and every night at the camp was a nightmare. Jewish people were mercilessly beaten, shot with guns and rifles, attacked by trained dogs, and hanged from the gallows. We were starved, humiliated, and tortured for no reason whatsoever. Most people were waiting to die and finish the horrors that their lives had become.

In the camp, construction work went on without interruption. We were forced to build barracks, roads, streets, and shops. We worked under tremendous pressure and constant fear. Commander Goeth was an evil beast—who enjoyed his job. He used to walk or ride his white horse around the camp, always with a gun in his hands. He shot and killed people for target practice. Perhaps he didn’t like the way someone looked, or the way another person walked. He would have no mercy on those who needed to take a break from work. They would be shot without notice. Under Goeth’s direction, other Nazis in the camp were encouraged to kill Jews for fun and sport. In addition, mass killing of Jews who disguised themselves as gentiles took place nearly every day on "Hujowa Gurka,” a hill overlooking the camp.

Most often, these despicable deeds were perpetrated by the Ukrainian camp guards. Dentists were called upon to pull out the gold teeth from the bodies before they were burned. Later on, the tooth extractions were performed before the executions took place. When the torturing and murdering were finished, gasoline was poured over the presumably dead bodies, which were then burned. I can recall the terrible smell of burning flesh and the smoke from the fires which burned my eyes. It is a terrible memory. Meanwhile, the Nazis amused themselves by frequently gathering prisoners on the "Appellplatz," where people were beaten, shot, or hanged.

During these times, music was played over the loudspeakers. When a Jewish prisoner was caught stealing food, committing a disturbance, whistling, or singing a song that the Gestapo or SS didn’t like it, we would all be called together at the Appellplatz to watch that prisoner’s execution, either by shooting or by hanging at the gallows. Two or three times a week, transports of Jews who were caught with forged (i.e., gentile) papers were brought to the camp to be killed at the Appellplatz. One scene that I will never forget happened in May 1944, when many small children were suddenly deported by truck from the camp.

They were surely headed to their deaths, fulfilling the Nazis mandate to kill all of the children, who represented the future of the Jewish people. Music blasted at high volumes over the speakerphones as the trucks became filled with young victims. Someone later told me that the song played that day was a German folk song titled, “Mommy, Buy Me A Horsie.” The cruelty was not to believe. I can remember the sounds of dozens of parents crying and pleading with the Gestapo for the lives of their children. The parents howled in desperation as the doors to the trucks were locked.

The trucks sped through the gates and the children were never seen again. An unusually large number of well-armed guards surrounded the Appellplatz on that day, just in case the Jewish prisoners might seek revenge and revolt. But, we stood helplessly and unarmed in our assigned places, cursing the Nazis, clenching our fists, yet afraid to act because of our pitiful odds. We knew that any act of revenge would be futile and would surely result in a massive loss of Jewish life—for the Nazis treated us as if we were worthless human beings, worthy the Nazis treated us as if we were worthless human beings, worthy only of working ourselves to the bone for them and then being killed.

Searching Safety in a Profession

Before the war broke out, my brother, Leszek, completed his studies to become a mechanic. This enabled him to find a better job as machinist/toolmaker at the camp. Unfortunately, I did not have any skills that could make my life any easier. Before the war, I worked in my father’s textile trading business and the skills I learned were not useful to the Nazis at the concentration camp. I knew I had to be productive to stay alive and I was not afraid to try something new.

When I learned about an announcement that electricians were needed at the camp, I immediately applied for the job. I did not know anything about electrical work, but my foreman and co-workers were very helpful and showed me what to do.Working as an electrician was much easier than building barracks. My electrician's armband and belt with electrical tools enabled me to move freely around the camp. I was lucky to have this job for quite a while. Breakup of my family at Plaszow

On August 6, 1944, my girlfriend, Regina, was sent to Auschwitz. Leszek was sent to Miak-Zschawitz-Dresden. Andin September 1944, Jacob's job at the "Kabel" Wermacht Munition Industries had ended. He arrived in Plaszow with a group of about 50 people. His group was told to prepare for a transport to another camp on the very next day. Once again, I had to try to save him. I hid Jacob under a bunk bed in my barracks with hopes that he would remain with me.

However, the next day, when some of the prisoners from Kabel didn’t show up for the roll call, the Nazis began to search for them with hunting dogs. Jacob left his hiding place and was caught. Fortunately, he wasn’t shot, but he was forced to join a transport to the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. Regina’s father was also put on that transport.

I never saw either of them again. After the war, I learned that Jacob was transferred from Mauthausen to St. Valentin, and then to Ebensee – so he experienced the worst concentration camps in Austria. He miraculously managed to survive, but he died from food poisoning just a few days after the war. I was devastated when I heard the news of his death. He went through so much, for so long, and survived, only to die after the horrors were over. This was very hard for me to take. A Beating that I’ll Never Forget

One day, a telephone call came to our electrician’s shop from the SS office with orders to change several light bulbs immediately. My foreman sent me to change the bulbs. I came face-to-face with SS Unterscharfurer Franz Simonlahner, the butcher, beast, killer, and boss of an infamous stone mining operation. My hand began to shake because I new that he was a sadist. Simonlahner had under his command a group of twenty to thirty men and women whose job was to dynamite rock at the mine and transport the broken stones in push carts to build the roads at the concentration camp.When I finished changing the light bulbs, Simonlahner handed me two or three cigarettes.

I was afraid to take them. Upon his insistence, I eventually took the cigarettes and politely thanked him. When I came back to the shop, I told my fellow workers what happened. No one believed me. Several days later, another call came to our shop from the SS office, asking that the same electrician who replaced the bulbs should come back to the office again. My foreman decided to accompany me in case something had happened to the lights. When we knocked on the door, we heard Simonlahner say: "Ja, ja, ja, come in!" My heart began to beat like a hammer, but Simonlahner only wanted new lights installed on the other side of the office.

We went to work at once. When we were nearly finished, Simonlahner asked the foreman to go back to the shop without me. When I was ready to leave, Simonlahner handed me another pack of cigarettes. I said, "Thank you, but no." He insisted that I "take it, take it, because I do not smoke." When I refused to take the cigarettes, he grabbed my hand and pushed the cigarettes into it. I thanked him again and began to walk out of the office, still wondering why he was being so good to me. Then he said: "Listen, I have more cigarettes and I want you to sell them. I want money to buy nice things." He gave me five packs of cigarettes to sell and told me to bring the money back to him.

Selling cigarettes at camp was a crime punishable by death, but paradoxically, I had to do it, for my life was in danger if I didn’t sell them. As it turned out, our arrangement worked well for quite a while. I came to Simonlahner’s office often to get bread, butter, candies, cigarettes, and anything else that was sellable. I had become a black marketeer. On September 15, 1944, Commander Goeth abruptly ordered to kill several Jewish policemen who knew that he had been stealing valuables from prisoners and kept them for himself, rather than to hand them over to the Nazi authorities. Chief of Jewish Police Wilek Chilewicz, along with his wife, Manek Ferber, two men by the names of Finkelstein and Schnitzer, and several others were murdered on the spot.

Their corpses were displayed on the ground for everyone to see. Every prisoner had to walk next to the corpses, and turn their heads in the direction of the corpses. We looked at the bodies because we had to in order to survive. Goeth was soon arrested for corruption and jailed. I think the Gestapo were angered when he killed the Jewish police, either because they were leading an investigation on his smuggling activities, or perhaps the Gestapo, too, were conducting illegal business with the Jewish police. Meanwhile, my days as a black marketeer were good. I was able to get a little extra food to eat. However, those days were about to end -in violence!

The last time I came to the SS Office, Simonlahner gave me ten packs of cigarettes. Like always, I paid him and put the cigarettes under my shirt. As I walked out of his office, he grabbed me by my hand and tried to pull me into another office. I put up a fight and struggled to get free, but I was afraid of him and his gun. When I stopped struggling with him, Simonlahner took me to the office of SS Oberscharfurer Hujar, another barbaric murderer at the camp. Simonlahner said to Hujar, “I bring you a black marketeer who has cigarettes under his shirt.” He did. Bleeding profusely, I managed to run to the tailor shop where my friend, Ted Wilk, worked. Ted and two other tailors washed me up and bandaged my head so that only my eyes were visible. That was how badly I was beaten. My nose never properly healed. The next day, Regina’s cousin, Judith Steiner, was shocked to see me all bandaged up. I told her what had happened and said that I was lucky to be alive. From that day on, I managed to avoid both Simonlahner and Hujar, who assumed I was dead. I was lucky to succeed in avoiding them during my remaining days at the Plaszow concentration camp.

Finishing out the War at Oscar Schindler’s Factory

By sheer luck, I was sent to Oskar Schindler's ammunition factory in Brinnlitz, Czechoslovakia, on October 15, 1944. The camp needed electricians, and I had gained some experience in the trade. My prisoner number was Heftling 68940, which was the number that was placed on what 40 years later would be called “Schindler’s List.” After 5 years in an environment of intense violence and countless deaths, I was feeling fairly worn down by the Fall of 1944. Had I not been placed on "Schindler's List," I might not have been able to stay alive for much longer.

The war was to go on for another 8 months, and the Nazis stepped up the pace of their inhumanity against the Jews. Increasing the rate of Nazi atrocities would be hard for anyone but a Holocaust survivor to imagine. Once again, I was aboard a cattle train – but this time it was really going to a labor camp. The train stopped at the Gross-Rosen concentration camp were I remained for several days. Then, I got back on the train and headed to Schindler’s factory in Brinnlitz, Czechoslovakia.

At the factory, I met a large group of prison workers who were treated much better than anywhere I had been since the outbreak of the war. There were no mass shootings. There was substantially more food than what I was given at Plaszow, and the prisoners were not tortured or concerned about their deaths. Some prisoners were fortunate to have been assigned to work at Schindler’s factories since the Krakow ghetto days in 1942, a full two years before I was able to be under his custody. The three electric wires I needed to connect were 15-20 feet above the floor, so I needed to use a ladder. I stepped on the ladder and hooked the first wire, then the second, and when I was about to connect the third wire, I accidentally touched it with the clamp of the first wire, creating a massive electric short that shut down the power to the entire factory. The factory was suddenly dark and quiet. I jumped off the ladder, a bit shaken, but not hurt. Within a short time, someone in the shop threw the circuit breaker and restored the power. The Nazi shop supervisor then arrived and asked me what had happened. When I told to him, he very angrily kicked me in the buttocks and ordered me to go to the shop where he said that he would meet me.

Fearful of what the Nazi supervisor would do to me, I decided to run to Oskar Schindler's house instead. I knocked on the door and Mrs. Schindler came to greet me. I told her what had happened and she asked me to wait outside for a moment. She called Oskar, who came to the door and said that he heard from his wife about the accident. I told him exactly what happened and I pleaded for his help. He instructed me to go back to the shop and wait for him there. When he arrived, he told the Nazi supervisor that he needed an electrician to work on his new apartment, which was being built just outside of the camp. When the supervisor recommended someone, Schindler looked around the room and pointed at me. "How about him?,"

To get to work each morning, I was escorted by the SS so that I would not run away. The working conditions were pretty good and the atmosphere was relaxed. I wouldn’t have wanted to escape even if I had the opportunity. I didn’t have a chance to thank Schindler for helping me. I wasn't able to speak with him until after the end of the war.

The Partisan Underground and Oskar Schindler’s Escape from Brinnlitz

After a few weeks in Brinnlitz, I met a small group of Jews, including five Russian Jewish POW soldiers who had been in concentration camps in Budzyn and Majdanek. I was invited to join them in an anti-Nazi partisan group that was to consist of twenty-five men. In order to safeguard most of the members of the group, each member was assigned to a unit of only five or six men. The members of each unit did not know the identities of the partisans in any of the other units. This way, if someone were to get arrested, the lives of the partisans in the other units would not be in jeopardy.

The men in my unit were Dubnikov, Jonas, Lipschitz, Miedziuch, and Pozniak. The partisans established contact with the Czechoslovak underground who were stationed in the nearby forest. They told us that the Russians were advancing on the battlefront and that the Germans would soon be defeated. There were rumors that the Nazis might step up their murderous activities at the extermination camps and prison camps, and possibly obliterate any evidence of what took place in them. The Czech underground supplied us with guns and rifles and warned us about a possible attack by the Gestapo and Waffen SS.

In the event of an attack, they told us to defend ourselves and assured us that they would come to our rescue. Oskar Schindler knew about the partisan underground group operating in his factory, but he didn't do anything to destroy it. Since he treated us well and tried to protect us, he probably didn’t feel threatened by the partisans. Also, he might have known that the Germans were about to be defeated and he needed to develop ties with the Jews to save his own life from the advancing Russian army (at several camps that had been liberated, the Russian army and angry groups of liberated prisoners tracked down Nazi camp officers and took immediate justice into their hands, hanging the officers for all to see).

I recall Schindler's farewell speech to us. "Do not thank me for your survival," he said. "Thank your fellow people, who worked day and night to save yourselves from extermination. You faced death every moment while you were at the Plaszow concentration camp." He asked us to keep a silent vigil for three minutes in memory of the countless victims who died during the past six years. Then, he provided the leader of the partisans with nine rifles and ten hand guns, but warned him not to use the weapons unless there was an emergency.

He also told the partisan leader not to give the weapons to any inexperienced men or women, because any gunshots heard outside of the camp could provoke the German army to enter the camp and slay all of the survivors. As it turned out, the Germans soon surrendered and the war in Europe came to an end. The underground partisans did not need to fight the SS or the Gestapo.

By operating successful ammunition factories, Schindler was able to find a non-military solution to make himself useful to the Nazi war machine. I also think that Schindler's adventurous disposition compelled him to bribe, outwit, and win over those in his path. Perhaps he risked his life to save Jews so that he could build a post-war alibi when the Germans were defeated.

Liberation and the Search for Family

After Schindler's departure, the underground partisan group took command of the camp. The leader of the partisans shut the gates and announced that no one could leave. The armed partisans, myself included, took positions at all of the doors and windows.The partisans immediately opened the kitchen so that all of the inmates could be fed. A Russian Jewish partisan named Elia Dubnikov, who survived Majdanek, Budzyn, Plaszow, and Gross Rosen, managed to catch one of the Nazi "capos" and drag him to the factory hall.

The capo had arrived at Brinnlitz from Goleszow during the previous winter with a cargo of Jews, most of whom were frozen to death. Now, it was the capo’s turn to be punished. Dubnikov mercilessly hung the Nazi capo to death on one of the steel beams in the factory. On the very next day, three Czech partisans came to the camp and yelled, "You are all liberated! You are free! The Red (Russian) army will be here in a few hours." Later that day, a Russian officer came to the camp and announced, "The war is over. You are free. There are no more concentration camps. You can go home or to wherever else you want to go." Surviving Jews from concentration camps throughout Europe began to move around from one camp to another, looking for their families.

Two or tree days after liberation, a friend (Lefkowicz) from Kracow-Podgorze came to Brinnlitz in search of his family. After we embraced, he told me that my brother, Leszek, was very sick with typhoid at the Theresienstadt concentration camp in Czechoslovakia and that he needed medical help immediately. I ran to the Russian Military Commandant’s office at our camp, and asked him to write a pass to allow me to go to Theresienstadt. Within an hour, I was at the train station with several friends who were in search of their own families. It took us all night to travel to Theresienstadt. When we arrived at the camp, we were met with a sign at the closed gates that read "NO ENTRY; TYPHOID FEVER.” There was an epidemic at the camp. I walked around the fence of the camp and found a hole, which I crawled through. I immediately came upon an acquaintance from Krakow who asked me, "Victor, what are you doing here?" I told him that I was looking for my brother.

He said that he would bring me to him, but he first wanted to take me to see someone else. We walked into the women's barracks, and several of the girls who knew me began to yell: "Rega, Rega, someone is here to see you!" I was shocked. My girlfriend, Regina, was alive. Against all odds, she had survived Auschwitz. We were thrilled to be together again.

Then, I asked the acquaintance to bring me to my brother. Before the war, Leszek was a very handsome teenager, about 180 pounds and six feet tall. When I saw him at the end of the war in Theresienstadt, he looked like a skeleton. Leszek weighed about 70 pounds and could hardly talk. We both cried and I told him that I was going to take him to Schindler’s camp at Brinnlitz, which had doctors and medicine. I assured him that he would be OK.

I went back to Regina and told her that I had to take my brother to Brinnlitz the next morning. I told her that the Russians were going to bring the survivors from Brinnlitz back to Krakow, and I asked her to try to get to Krakow as soon as possible. I said that I would be waiting there for her arrival. The next morning, I took my brother to Brinnlitz with my Russian friend, Elia Dubnikov. It took us twelve hours to get there by train. Dr. Biberstein and Dr. Hilfstein, both from Krakow, examined Leszek and gave him some medication.

However, they told me that he needed to be hospitalized. So, we boarded a Russian army train to Krakow, where I took Leszek to the Lazarz Hospital. The hospital did not have sufficient facilities to help him. One of the physicians told me that if I wanted to save my brother’s life, I had to take him to the American zone for special medicines that were not available in Poland. But I needed to wait for Regina to come to Krakow. She was recuperating in Theresienstadt from her own horrible experiences, including the death of her parents and sisters, and she was pondering what to do with her life.

While in Krakow, I learned about atrocities that were taking place against the Jews across Poland, despite the fact that the war was over, and despite all that we had been through. The Poles were conducting pogroms - in Krakow, Kielce, Nowy Targ, Rabka, and other towns and cities. They did not want the Jews to come back home and reclaim their belongings! Houses, apartments, property, businesses, and stores seized by the Nazis were taken over by the Poles, who had no intention of returning the stolen assets to us.

The Poles began to shoot the Jews who were coming back home. Anti-Semitism in Poland was on the rise (it never disappeared). It became apparently clear to me that there must be better places to live than in Poland.

Palestine and America seemed like good alternatives to me. But I couldn’t spend too much time thinking about emigrating at this time. Regina arrived in Krakow four weeks later, on July 1, 1945. On the very next day, we were married at the home of Rabbi Levertow. The ceremony, attended by ten close friends and several cousins, was meaningful but not very romantic. It lasted about 20 minutes.The following day, our group of survivors, mostly from Schindler’s camp at Brinnlitz, left Krakow for the American Zone in Austria.

Renewing Our Lives in Austria

Our mission to Austria was to get Leszek some medical attention, find a good displaced person’s camp to live, and try to find my youngest brother Jacob. Someone had told me that he survived the Holocaust and that he was last seen at the Ebensee concentration camp in Austria. Leszek was very sick at this point, but the people in our group helped me to take care of him. I was fortunate to be with a truly caring group of people, most of whom I remained very close with when we moved to America.

We obtained border passes from Polish authorities to go to Czechoslovakia, but when we arrived at the town of Budzejowice, the Russian army would not let us pass through the Austrian border. The next morning, I walked through the forest with my friend, Joe, to find a place to cross the border. There was no place to cross. About an hour later, we saw four American trucks loaded with Jewish survivors from the Mauthausen concentration camp. The survivors were dropped off at the Railroad Station so that they could go back to Poland and search for their families. My wife, Regina, recognized her uncle, Shulem, among the Mauthausen survivors. We were most happy to see him, alive and well, and in search of his wife and son. Unfortunately, as he learned later, they did not survive. We told him that his sister-in-law, Helen, who was also Regina’s aunt, was liberated at the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

He was glad to hear the good news. We later learned that Shulem and Helen got married in Krakow and moved to Israel. I approached an American army officer and, through an interpreter, I asked him to help us enter Austria. When he saw Leszek’s bad condition, he called a Polish-speaking American soldier and asked him to help us. The soldier put two people from our group into each of his trucks, and covered us with blankets so that the Russians would not see us. When we arrived at the other side of the Austrian border, he wanted to let us off. Joe and I begged him to take us all the way to Ebensee, which he was reluctant to do. But when he noticed Leszek's poor health, he offered to take all of us on one truck to Gmunden. He said that we had to be on our own from there.

But the outcome of my little brother, Jacob, was not as lucky as Leszek’s. I was unable to find him in Ebensee and no one would provide me with any information about his whereabouts. But when my friends saw that Leszek was recovering and that he would survive, they told me about Jacob’s fate. He did survive the horrors of the Holocaust and he was liberated at the end of the war in Ebensee, as I had heard.

But tragically, he died at the camp just a few days after liberation. Perhaps he died from malnutrition. Or, perhaps he ate some spoiled food. No one knew for sure. But for me, my search for Jacob was over. I would never see my youngest brother again. Epilogue In October 1965, I was asked to come to the German Consulate in New York to identify SS Obersturmfuhrer Martin Fellenz, the sadist Nazi commander of the Krakow ghetto deportation who ripped-up my working papers and ordered thousands of Jews, including my parents, brother, sister, and me, to board the transport to the gas chambers of Belzec, under extremely violent and inhumane conditions. At the consulate in New York, I was asked to identify Fellenz’s picture in a photo album of about 50 SS officers. I was able to point to Martin Fellenz’s photograph right away. When I was asked if I was interested to be a witness for the prosecution at Fellenz’s trial, to be held Kiel, Germany, I said that I would go gladly. I was eager to seek revenge for the horrors he committed. During the court proceedings in Kiel, I came face to face with Fellenz after some 20 years. It was a tense moment for me to be inanti-Semitic Germany--the country that tried to exterminate my people--testifying against a former Nazi German officer. The judges asked me if I could recognize the accused. I remembered his vicious face immediately. Pointing to Fellenz, I said, "Yes, this is the man who killed thousands of Jews, including my parents and my sister." Fellenz denied that he ever knew me, which was true. I was just one of tens of thousands of Jewish civilians that he was responsible for imprisoning, torturing, abusing, and killing in the Krakow ghetto. After the trial, I returned to the United States. I never found out whether Fellenz was convicted or set free, and I didn’t really want to know--for I thought it was entirely possible, even probable, that despite all the evidence against him, the German government just might set him free. Source: Hardships and Near-Death Experiences at the Hands of the Nazi SS and Gestapo (1942-1945) By Victor Lewis

{1} Mr. Lewis was a witness at the 1965 criminal trial of Martin Fellenz in Kiel, Germany. See page 39 for an account of the trial, published in the German newspaper "Kieler Schwurgericht." {2} Mr. Lewis’ escape from the Belzec transport was briefly described in the "Kieler Schwurgericht” newspaper article (Kiel, Germany) in October 1965 following his testimony against Martin Fellenz. * Some photos and formatting have been changed from the original text. Copyright Victor Lewis 2000. H.E.A.R.T 2009

|