Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

|

|||||||||

Women Record Their Accounts of the Holocaust

Melita Maschmann Bund Deutscher Madel Member

“On the night of November 9 1938, the “Crystal Night” a shadow fell on our joy. Of the riots of that night I saw nothing. But in the morning I saw the wreckage of the little shops and restaurants in an alley near Berlin’s Alexanderplatz, where the inhabitants were Jews.

I was horrified at the violence that must have raged there. But didn’t we hear all the time that international Jewry was inciting the world against Germany? And now the Jews had had a frightful warning.

I expelled this episode from my mind as quickly as I could. It meant sorrow for innocent people – for what had these little men, whose little shops were destroyed, to do with international Jewish capitalism?

It was simpler not to dwell upon these things, but to plunge oneself quickly back into one’s own work.”

Emmy Bonhoeffer Sister-in-law of German Resistance martyr Pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer

“Standing in line for vegetables or something like that I told my neighbour standing next to me that now they start to kill the Jews in the concentration camps and they even make soap out of them.

And they said Frau Bonhoeffer, “if you don’t stop telling such horror stories you will end up in a concentration camp too and nobody of us can help you. It’s not true what you’re telling, you shouldn’t believe those things, you have them from the foreign broadcasts and they tell those things to make enemies for us.”

Going home I told that to my husband and he was not at all applauding to me and the very contrary he said, “My dear, sorry to say but you are absolutely idiotic what you are doing. Please understand the dictatorship is like a snake.

If you put a foot on its tail, as you do, it will bite you. You have to strike the head and you can’t do that, neither you or I can do that. The only single way is to convince the military who have the arms to do it, to convince them that they have to act, that they have to make a coup d’etat.”

Hertha Beese Berlin Housewife and Social Democrat

In the flat underneath ours lived a Jewish family. The only reason they had not yet been persecuted and taken away was that the father was Italian and belonged to Mussolini’s party.

But when we ourselves faced more and more difficulties the wife began to feel insecure and was scared that they might take her away despite the Italian connection and she therefore left.

So that there flat became empty and I begged that it should not be handed over to the landlord since we still hoped there would be a total collapse and we would be rid of our difficulties.

I looked after the empty flat and one night, it must have been around midnight, the doorbell rang. I opened and there stood in front of me a Jewish couple. This was how I began to help persecuted Jews. All of a sudden I had entered an invisible circle of people who smuggled Jews about.

As soon as one hiding place had been detected they were quickly passed on. They would always move about by night. I have never found out who it was who sent them to me in the first place. Some decent people

The problems started with the feeding of the Jewish people since they neither had food-rationing cards nor very often any money. So we in turn had to make use of friends who exchanged their smoking cards for the odd potato or bread, or a friend would come and leave a bit of food.

But all this was so illegal that names, sources or contacts had to remain unknown.”

Toshia Bialer Warsaw eyewitness – Moving into the Warsaw Ghetto – October 1940

“Try to picture one-third of a large city’s population moving through the streets in an endless stream, pushing, wheeling, dragging all their belongings from every part of the city to one small section, crowding one another more and more as they converged.

No cars, no horses, no help of any sort was available to us by order of the occupying authorities. Pushcarts were about the only method of conveyance we had, and these were piled high with household goods, furnishing much amusement to the German onlookers who delighted in overturning the carts and seeing us scrambling for our effects. Many of the goods were confiscated arbitrarily without any explanation.

In the ghetto, as some of us had begun to call it, half ironically and in jest, there was appalling chaos. Thousands of people were rushing around at the last minute trying to find a place to stay.

Everything was already filled up but still they kept coming and somehow more room was found. The narrow crooked streets of the most dilapidated section of Warsaw were crowded with pushcarts, their owners going from house to house asking the inevitable question: Have you room?

The sidewalks were covered with their belongings. Children wandered, lost and crying, parents ran hither and yon seeking them, their cries drowned in the tremendous hubbub of half a million uprooted people.”

Rita Boas- Koupmann Dutch –Jewish Teenager survivor of Auschwitz – Birkenau

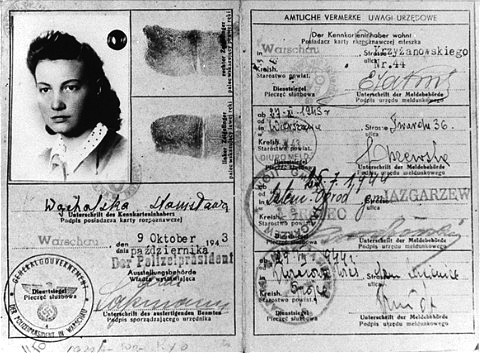

“I think the alarm started when Jewish people had their card with a “J” on it. That was the first time they marked you, you had your identity card you had to carry with you and what was special was the “J” in it and you were marked because anybody could ask for the card.”

Riva Losanskaya Jewish survivor from the Einsatzgruppen murder action in Butrimonys Lithuania

On the 9 September 1941 740 Jewish men, women and children were murdered at Butrimonys – Einsatzgruppen Report.

“I thought they would kill everyone, and if anyone survived they would be cursed. But I still had a glimmer of hope, until the very last moment, of course we were frightened and not heroes, but I still had some hope that I might escape.

One woman said to me, “You’ll manage to escape.” I asked her, “Don’t you want to escape with me?” She replied, “What about my child?”

We were going in that direction, along this road, and saw a deep ditch – grass has grown over where it was. But in one place there was an open area covered in sand. When I saw it, it struck me that I could get away.”

Dina Mironovna Pronichev Jewish survivor from the Babi Yar mass murder carried out by Einsatzgruppen forces in Kiev on 29 / 30 September 1941.

“We had two children: a boy and a girl. Before the war I worked as an actress at the Kiev Children’s Theatre. On the second day of the way my husband joined the Soviet Army, and I was left with two children and my old sick mother.

Hitler’s troops seized Kiev on the 19 September 1941, and from the very first day they started plundering and killing Jews. Terrible stories about the treatment of Jews were circulating in the city. We lived in terror.

When I saw announcements posted in the streets, ordering “all of the Jews of the city of Kiev to gather at Babi Yar. I felt trouble was coming. I started shivering. I say that nothing good was awaiting us there. That is why I dressed my children, three and five years old, packed their stuff in a small bag and took them to my Russian mother-in-law. Then following the order, my sick mother and I went along the road to Babi Yar.

Jews were walking in hundreds and thousands. Besides me there was an old Jew with a long white beard. He had on a tallis (prayer shawl) and tfilin (phylacteries). He was mumbling. He prayed exactly as my father did when I was a child. A woman was walking ahead of me. She was carrying two children and a third one was walking alongside, holding her skirt.

Sick women and elderly were riding in carts among piled up bags and suitcases. Small children were crying. Old people, having trouble walking, sighed and trudged on in their mournful journey.

Russian husbands were walking with their Jewish wives. Russian wives were walking with their Jewish husbands. When we approached Babi Yar I heard shooting and inhuman shouting. I started to grasp what was going on, but did not say anything to my mother.

When we entered through the gates, we were ordered to turn in our papers and valuables and undress. A German came over to my mother and tore a gold ring off her finger. Only then mother said, “Dinochka, you are Pronicheva, you are Russian. You should survive. Rush to your children. You should live for them.”

But I could not flee, we were surrounded by fascists with sub-machine guns, Ukrainian policemen, and ferocious dogs who were ready to tear a human being to pieces. And then I could not leave my mother alone. I embraced her, burst into tears, but was unable to leave her. Mother pushed me away and yelled, “Hurry!”

I went to a table at which a fat officer was seated, showing him my passport and said quietly, “I am Russian.” He was contemplating my passport when a policeman came over and barked, “Don’t believe her, she’s a Kike. We know her….” The German told me to step aside and wait.

I saw groups of men, women, children and elderly undress. They were taken to an open pit and shot by soldiers. Then another group would come. I saw this horror with my own eyes. Even though I was not standing close to the pit, I could hear awful shrieks of terrified people, weak voices of children, crying, “Mother, mother….”

I saw all that and was unable to understand how people could kill others because they are Jewish. And I concluded that the fascists were not humans, they were – beasts.

I saw a young completely naked woman feed her naked baby with the breast, when a policeman came to her, took the baby, and thrust it into the pit. The mother rushed after the child. A fascist shot her dead, and she fell into the pit. Had someone told me this, I would not believe it. It is impossible to believe.

The German who had ordered me to wait, took me to his superior, gave him my passport and said, “This woman says she is Russian, but a policeman says she is Jewish.” The officer studied my passport for a while and then said, “Dina is not a Russian name. You are Jewish. Take her.”

A policeman told me to undress and pushed me to the edge of the pit where another group was waiting for its fate. But before the shooting started, I driven by terror, fell into the pit. I fell on dead bodies. At first, I could not understand anything: Where was I? How did I get there?”

I thought I had gone mad. But when people started falling on me, I came to my senses and understood everything. I started checking my arms, legs, abdomen, head, it turned out I was not even wounded. I pretended to be dead.

Under me and above me there lay the killed and wounded. Some of them breathed, others moaned. Suddenly I heard a child cry, “Mommy!” It seemed like it was my little daughter. I burst into tears. The execution went on, and people kept falling, I was pushing corpses away in fear of being buried alive. But I did this in a way so that the policemen would not notice.

All of a sudden everything was quiet. It was getting dark. Germans with sub-machine guns were killing those who had been wounded. I felt someone was standing above me, pretended to be dead, no matter how hard it was. Then I felt we were being covered with earth. I closed my eyes to protect them.

When it became completely dark and quiet – deadly quiet in literal sense – I opened my eyes and having made sure no one was around and watching me, I dug myself out of sand that was covering me. I saw the ditch filling with thousands of killed. I got scared. Here and there earth was moving – half alive people were breathing.

I looked at myself and got scared. The undershirt that was covering my body was all bloody. I tried to get up and could not. Then I said to myself, “Dina, get up, leave, run from here, our children are waiting for you.” I got up and ran.

Suddenly I heard a shot and understood that they noticed me. I fell on the ground and waited. All was quiet. Without getting up, I started moving toward the high hill that surrounded the pit.

Suddenly I felt something was stirring behind me. First I got scared and decided to wait for a while. I turned quietly and asked, “Who are you?” A delicate, scared child’s voice answered, “Don’t be afraid, it’s me. My first name is Fina, my last name is Shneiderman. I am eleven years old. Take me with you, I am very afraid of the dark.” I moved closer to the boy, embraced him and started crying. The boy said, “Don’t cry.”

We both started to move quietly. We reached the edge of the pit, got some rest and continued climbing, helping each other. We had already reached the top of the pit, stood up to run away, when a shot was fired. We fell on the ground instinctively. For some time we were quiet, being afraid to speak. Having calmed down, I moved closer to Fimochka, touched him and asked in a whisper, “How are you doing, Fimochka?”

There was no answer. In the dark I could feel his legs and arms. He did not stir. No signs of life. I got up a bit and looked in his face. He was lying with his eyes closed. I tried to open them but understood that the boy was dead. Probably, the shot we heard had taken his life.

I caressed his cold face, said goodbye to him, got on my feet and ran. Having made sure that I was far from the terrible place called Babi Yar, I decided to approach a house that could just about be seen in the dark. Shivering, I came to a window and knocked. In a few minutes a sleepy woman lifted up a curtain and asked, “Who is it? What do you want?” I answered her, “I escaped from Babi Yar.”

And then I heard her angry voice, “Go away. I don’t have anything to do with you.” I left. I ran, because the day was breaking and I knew that they should not see me there. But there was no place to go, so I approached a second house and knocked. The door opened, and an elderly woman appeared on the porch. When she saw me in the undershirt, she crossed herself and recoiled.

“Who are you?” Where have you come from?” she asked. I replied, “Don’t be afraid, dear. I am not a devil. I’m human.” And then I lied for the first time in my life. “I’m Ukrainian. I saw my friend to Babi Yar and barely escaped.” The old lady took my hand and let me in. Then she told me to wash myself, gave me a clean shirt, a blouse, a skirt, and old shoes. I looked at myself and got a shock: a real Ukrainian!

My hostess gave me a glass of hot milk with homemade bread and told me to get some rest. I ate with gust, went over to the old lady, embraced her, kissed her, and burst into tears. My saviour also cried. But having wiped her tears with an apron, she said, “Daughter, I know who you really are. But we are all alike for God. We have one God. Because I have helped you, my two sons will come back from the war alive.

But my place is not safe for you. Police hounds search here every day. They are looking for Jews. These beasts pay money for Jews. Now, go get some sleep. I’ll give you some provisions and try to get to our people. May God help you.”

I felt relieved because there were good people on earth who were ready to help others. The old lady made my bed and left. I slept for a while but could not sleep long. The images of the previous day were passing in front of my eyes. I believe I heard shots, shouting and children crying somewhere….

Who knows where my children are? Did my mother-in-law manage to save them? I did not have time to think. I was aware that the old lady could suffer because of me. And I decided to go. I looked in a mirror and was terrified to see my hair gray. This is from last night, I thought.

I put some soot on the face to seem older, wrapped my head in a kerchief, as was done by old Ukrainian women, and said good-bye to my dear hostess and set out for the Daritsa. My friend Natalia, with whom I had played in the theatre, lived there.

At first glance Natasha did not recognise me. When she did, she got scared. She told me take off my clothes and get some rest. But I felt something un-natural in her attitude toward me. There was some alienation.

Once we had eaten, she said to me, “Dina, I should tell you the truth. You can’t stay here for a long time. My husband Andrei deserted from the Red Army. He hates the Soviet power and the Jews who invented it. I’m afraid he’ll inform on you. You’d better leave.” And I left.”

Theresa Stangl Wife of Franz Paul Stangl – Commandant of Sobibor Death Camp

“But I was very glad when Paul told me he had arranged for us to move to the fish-hatchery – it would be better for all of us, and I was glad to get the children away from that house. No, while we were in Chelm, Paul was on leave, it was when we moved to the fish-hatchery that he had to go back to work.

And one day while he was at work – I still thought constructing, or working at an army supply base – Ludwig came with several other men, to buy fish or something. They brought schnapps and sat in the garden drinking.

Ludwig came up to me – I was in the garden too, with the children – and started to tell me about his wife and kids, he went on and on. I was pretty fed up, especially as he stank of alcohol and became more and more maudlin.

But I thought, here he is, so lonely – I must at least listen. And then he suddenly said, “Fuchterlich, - dreadful, its just dreadful, you have no idea how dreadful it is.” I asked him, “What is dreadful?” “Don’t you know? he asked. “Don’t you know what is being done out there?”

“No. What?” “The Jews are being done away with. Done away with I asked, How? What do you mean?” With gas, he said. Fantastic numbers”

He went on about how awful it was and then he said, in that same maudlin way he had, “But we are doing it for our Fuhrer. For him we sacrifice ourselves to do this – we obey his orders.” And then he said, too, “Can you imagine what would happen if the Jews ever got hold of us.”

Jenny Schaner A native of Austria, she was arrested by the Gestapo in October 1941 and deported to Auschwitz in July 1942.

“We had to put down all our bags. Men were sent to one side, women to the other, on the right side, stood SS men with loaded carbines. The arrivals were locked up for the night in a block without water and without toilets; the next morning they saw the miserable people who populated the compound through a small window. “We thought they were Russian prisoners of war, later we found out that they were women.” That same morning the new prisoners were “acclimatised,” we had to strip completely, our heads were shaved, and then we were given striped dresses and wooden clogs. We couldn’t walk in them, and after twenty-four hours my feet were blistered. They went out to work past Camp Commandant Schwarz.

We had to build a pond. That was terrible. Young SS men were running around hitting the women over the head with shovels. We couldn’t understand the whole thing. We didn’t know what was happening to us. I did this for ten days.

The Dutch women suffered particularly, that they found it more difficult to bear up. One of them turned to the work-detail leader and begged him, “For God’s sake, sir, I cannot work like this, I am pregnant.” And the SS man answered, “What you swine, you pig!” Then he knocked her down and she was carried away on a stretcher.

I was so desperate that I told a female guard that I could not do this much longer and asked whether there wasn’t any office work; I was a stenographer – typist. “Perhaps,” she said and told me not to go out to work the next morning. I then stayed in the block and was taken out of the work detail. First she worked in the admissions office where she saw much misery.

One day an SS man asked her, “Do you have strong nerves?” She said yes and came to the Political Section, to the “registry” where the death lists were kept. Personal data, day of death, and cause of death had to be entered, with great precision. If there was a typing error, they might become terribly angry.

In the death books were entered the names of those who had died in the camp as a result of sickness or on the electrified barbed wire, or had been shot, or hanged by the execution squad. Not “processed” were those who had been sent directly from the ramp into the gas ovens. The individual death reports were signed by doctors.

Most of the recorded causes of death were fictitious. Thus, for example, we were never allowed to enter “shot while escaping” in the book. I had to write “heart failure.” And “cardiac weakness” was the cause listed instead of “malnutrition.”

The three prisoners wrote for fourteen to sixteen hours a day. Personal data and causes of death filled line after line, page after page, and still it wasn’t possible “to include all the daily deaths.” The families got letters saying that despite the best possible medical care, it was not possible to save the life of the prisoner:

“We express our heartfelt condolences at this great loss. Upon request you may get the urn against a payment of 15 marks.” The urn of course, did contain the ashes of someone, but not those of a particular person.

One day approximately fifty children one day were brought to the camp by truck. The oldest were five years old. I still remember a little girl, she might have been four. A little girl went up to Quackernack (an SS man) and said something to him.

The boy whose hand she held was perhaps a year older, he may have sensed something….. With her little brother at her side she stood there and lifted her little head and asked something….. Quackernack kicked her. She lay sprawling.

All the children were crying. We too were crying. We were horrified. Then they took their baggage up again and followed Quackernack. I don’t know where he took them.”

Eugenia Samuel Polish eye-witness who lived near the Treblinka death camp

“I will never forget what I saw not till my dying day. Those little children, those people, what did they ever do to anyone? What did they ever do?” It was a terrible thing.

The decomposing human corpses caused such a stench, it was just terrible., you couldn’t go out in the yard, no way could you open a window or go outside.”

Hella Fellenbaum – Weiss Re-counts her deportation to Sobibor from Wlodawa in November 1942

“We left Wlodawa for Sobibor in carts. One might wonder why so few of us tried to escape, since we knew the fate awaiting us. True, my brothers and I were still children, but why didn’t the adults revolt?

Our cart was guarded by an armed Ukrainian who was watching us. German soldiers with machine guns rode alongside us on horseback. At the border of a wood, my young brother gave a farewell sign, left the cart and started to run, followed by my older brother. My little brother fell; the other escaped. I learned later that he too, was murdered.

I am confused about the time of our arrival at Sobibor, I can only remember that we crossed a forest and then I saw an inscription on a poster: “Sonderkommando Sobibor.” As in a dream, I heard a German ask, “Who can knit?” I stepped forward. The German asked me to leave the crowd and took me to a barrack with two other girls.

My mother had taught me how to knit socks. I knitted for the SS and Ukrainians; I also ironed shirts. Carpenters made me a stool on which I stood when the SS came to visit us, it was vital that I should look taller and older than my age.”

Claude Vaillant Couturier French born survivor of Auschwitz who arrived in Auschwitz on the 27 January 1943

“They were taken to a red-brick building, which bore the letters “B-a-d,” that is to say “bath.” There, to begin with, they were made to undress and given a towel, before they went into the so-called shower room.

Later on, at the time of the big convoys, they had no more time left to play-act or to pretend; they were brutally undressed, and I know these details as I knew a little Jewess from France, who lived with her family at the “Republic” in Paris. She was called “Little Marie.”

Little Marie was the sole survivor of a family of nine. Her mother and her seven brothers and sisters had been gassed on arrival. When I met her she was employed to undress the babies, before they were taken into the gas-chamber.

Once the people were undressed they took them into a room which was somewhat like a shower room, and gas capsules were thrown through an opening in the ceiling. An SS man would watch the effect produced, through a porthole.

At the end of five or seven minutes, when the gas had completed its work, he gave the signal to open the doors, and men with gas masks – they too were internees – went into the room and removed the corpses. They told us that the internees must have suffered before dying, because they were closely clinging to each other and it was very difficult to separate them.”

Alexsandra Teryentyevna Kirpa Ukrainian maid who worked in the German quarters in the Treblinka death camp

“During the period from 23 February until September 1943 we stayed in the camp in the town of Treblinka in Poland. In this camp the Germans conducted mass killing of people.

With what methods the Germans killed the people I do not know, but from the words Marchenko, Ivan, Ivanovich identified by me, I know in the camp there was a stationery gas “dushehubka” Besides, that I myself saw the glow of a fire and smoke from bonfires over the camp around the clock and the smoke, and there was a strong smell of burning bodies.

In this camp I worked as a maid cleaning the quarters of the German soldiers who guarded the camp. The camp was divided into two parts, in one part were located the guards and service personnel (including me).

In the second part were kept the prisoners and the mass killing of people took place. We service personnel were not allowed into the second part of the camp. In the camp there was a detachment of SS – 120 strong consisting of Ukrainian and Russian. This detachment guarded the camp and conducted the killing of people.

Marchenko personally told me and my girlfriends in the camp that he worked as a machinist in the gas “dushehubka,” he worked 24 hour periods, i.e. worked for 24 hours and was off duty 24 hours.”

Feigele Peltel In hiding on the Aryan, watching the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising April 1943

“On the balcony of the second floor a woman stood wringing her hands. She disappeared into the building but returned a moment later, carrying a child and dragging a featherbed, which she flung to the pavement to break her fall. Clutching her child, she started to climb over the railing. A spray of bullets caught her midway – the child dropped to the street – the woman’s body dangled lifeless from the railing.

By now the flames had enveloped the upper floor, their rise matched by the increased frequency and intensity of the explosions. Jews were jumping out of windows, some of them caught by bullets in mid-air, others shot on the ground.

Two Jews opened fire from the third floor, then retreated. A knot of people stood crowded in a third-storey window, lowering a rope to the ground. One man, then another, climbed out of the window and slid down a rope. The Germans opened fire, and both fell to the pavement. The cough of the machine gun mixed with screams of agony.

Dawn came quiet and ghastly to the ghetto, revealing the burnt shells of the buildings, the charred, blood-stained bodies of the victims. Suddenly one of those bodies began to move, slowly, painfully crawling on its belly until it disappeared into the smoking ruins. Others began to show signs of life, the enemy was on the alert, a spray of machine gun fire- and all was lifeless again.”

Bertha Sokolovskaya A Twenty-one year old witnessed the deportation from the Bialystok ghetto on the 16 August 1943

“I went home. At that time I had with me my very sick mother whom I managed to hide with great difficulties during the first raid. I couldn’t tell her anything. She began collecting some clothes and was terribly agitated because the hinge of the cupboard came off and she was worried how she could leave without closing it.

The scale of the tragedy did not reach my mother’s consciousness. It was still daytime and she said, “Go to the Judenrat, maybe you’ll be able to find out something,” and suddenly she added, “My darling little girl, perhaps you will be saved.”

I went to the Judenrat where the Sonderkommando already were bossing the whole show. Smart, elegant Barasz was trying to ingratiate himself, but I saw for myself that they were no longer speaking to him, they were just ordering him about and kicking him.

I went into the building of the Judenrat where all its members were gathered. Everybody was in a great state of agitation. We all finally understood that the end had come. I left the Judenrat and went – no, it’s more accurate to say – I joined the group of young people, and we found a bunker, where we hid for several days and where preparations were being made for an uprising. We had bottles filled with molten lead.

When we were discovered and turned out, we were put against the wall. We thought that we will be shot, but instead we were driven into the general stream of people on the road heading towards Boyary, the eastern railway station on the outskirts of the town, and to the goods trains.

It was horrifying. The stream of people were shepherded by barking dogs and were kicked with rifles by the Germans and by the Ukrainian Gestapo dressed in black uniforms. The Ukrainians, ordered by their masters in white gloves, did all their dirty work.

People who had a right to live walked on the pavement, maybe I am wrong, but I think they were indifferent to us. Our march was long and tortuous. Finally we reached our destination, the large square. After having been sorted out, the goods trains were leaving. Panic- stricken, we hung on to each other. We were hit with rifles, we were pushed and shoved like cattle.

I saw my aunts and a cousin. They told me that my mother had already left and that she hoped I managed to hide somewhere. The Ukrainians were beating us and were stealing from us. We were lying on the ground, above us a star-studded sky on a warm August night. Every now and then cries of prayers and screams of “Hear O Israel” were heard.

In the morning they began to separate families. The Ukrainian women kept on laughing sadistically saying, “Kiss good-bye, you’ll never see each other again.” The men separated from the women. I cannot describe the horrific heartrending screams of anguish and weeping.”

Alice Lok Cahana Hungarian Jewess talks about the deportation from Sarvar, in cattle trains and her arrival in Auschwitz – Birkenau in 1944

“The scene of going out of Egypt came to my mind. When we saw the cattle trains, I told my sister it’s a mistake they have cattle trains here – they don’t mean we should go in cattle trains.

So we found ourselves in the cattle train – they are closing the door on us and are leaving a bucket for sanitary use and a bucket for water. I told Edith I will never use a sanitary bucket in front of these people, no matter what happens to me. The two of us went into a corner of the cattle train.

On arrival at Auschwitz- Birkenau Ramp:

When we arrived I told Edith nothing can be so bad like the cattle trains. I am sure they will want us to work and for the children they will give better food. So they are saying right now the children should separate, “Go in another group – Go line up with the children.”

And I went to that group with the children and I was very tall for my age. Suddenly a German soldier asked me, “Do you have children?” I said no I am just fifteen in German and then he put me to another group.”

Ibi Mann Jewish prisoner excavated from Auschwitz- Birkenau in the Death Marches in January 1945.

“If anyone even dared to bend down to get muddy snow off their shoes, they were shot. That was the end. We weren’t allowed to bend over, we could only walk quickly, quickly, quickly. On both sides of the road there were ditches, big ditches and the ditches were full of bodies.”

Sonia Reznik Rosenfeld A Jewish survivor of the Pruszcz, sub-camp of Stutthof, recalled the moment of her liberation.

As the horrible scene in the barracks met the eyes of the officer he stood transfixed and speechless. Then our redeemer, standing at a distance lest he be infected by our lice, asked us who we were? We told him we were Jews. To this he answered, “You are free! Go where your hearts desire. Our Red Army has freed you from murderous hands.”

Everyone lay motionless, no-one could utter a word. It is impossible to be freed when one already has one leg underground. As I could speak Russian better than anyone there, I told the officer that we were half-dead people, and I asked him where we would go, and how we would get there as none of us had a home any more for Hitler’s hordes had shot everyone’s family.

The officer sighed, and with eyes full of pity he said, “Don’t be disheartened, unhappy women, as long as your pulses throb within you, you will yet be people like everyone else. Remain in your places and we will take you to our military hospital. There you will convalesce and each one of you will be able to go on your way.”

Sources:

History of the Second World War, published by Purnell London 1966 The World at War by Richard Holmes, published by Ebury Press 2007 The Holocaust by Sir Martin Gilbert, published by Collins London 1986 Into that Darkness by Gitta Sereny, published by Pimlico London 1974 The Nazis – A Warning from History – BBC TV Programme 1997 Auschwitz – The Nazis & the Final Solution – BBC TV Programme 2005 Sobibor – Martyrdom and Revolt by Mriam Novitch, published by the Holocaust Library New York 1980 Holocaust Historical Society

Copyright Chris Webb H.E.A.R.T 2009

|

%20issued%20by%20the%20Reichshauptstadt%20Berlin.jpg)

%20in%201949.jpg)