Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Szymon Srebrnik Chelmno Survivor Testimony

Protocol of the Interrogation of the Witness

On June 29 1945 in Kolo

Examining Judge of District Court in Lodz – Wladyslaw Bednarz

Assisted by Recording Clerk

In the presence of the parties - heard a testimony (not under oath) of the witness mentioned below. After the witness had been informed of criminal responsibility for a false testimony and acquainted with the text of article 106 of the Code of Penal Proceedings, he testified the following:

Up to March 1944 I had been in the Lodz ghetto, from where I was then driven off to Chelmno. In Lodz I worked in the ghetto in the so-called metal department.

In March 1944 the Germans organised a round-up. They caught me while I was on a street car and led me to Balucki Square where there were some cars from Chelmno. We were loaded inside and driven off.

Besides me there were 50 other Jews on the truck. Among them were Zydenfeld, Berek, Modownik, Kalmuszewicz, Huskiel. I cannot recall any other names.

The Germans took us a granary on the grounds of the Chelmno palace. There were no other Jews. We found out that we were in the Sonderkommando camp. An hour later the prisoners were divided into two groups. The stronger and better workers were sent to the woods, they formed the so-called “Waldkommando.”

The “Waldkommando” chief was Lenz. Other Germans employed in the woods were Runge and Kretschmer. The Hauskommando chief was Hafele.

The Waldkommando consisted of about 40 Jews, the remainder was assigned to the Hauskommando. We were all shackled. The shackles prevented us from walking in a normal way. We had to take very short steps. The shackles on our ankles were also chained to our waists.

We slept in the granary on a cement floor. It was very cold. The members of the Waldkommando told us that they were building two furnaces in the wood. They did not know what purpose they would serve, but they expected the furnaces might be used to make charcoal.

The furnaces were very primitive they stood on a cement foundation and were narrow at the bottom, gradually becoming wider at the top. They were approximately three metres (10 feet) tall. The width was about the same.

The fire grate was made of narrow-gauge railroad railings. There was neither a chimney nor a special trench for better draught. Later I was in the woods a few times so I could see the furnaces.

Officers Runge and Kretschmer were responsible for the construction of the furnaces. The construction process lasted about two weeks. Jews building the furnaces were sometimes killed for entertainment

Lenz and the Sonderkommando Chief – Commissioner Bothmann showed extreme cruelty. At times out of 30 workers sent to the woods, only 14 returned. The group of workers were constantly supplied with new men brought from Lodz.

Although each of eight transports brought 30 workers, it was still not enough, because so many of them were killed. When the first transport arrived, there were only 18 Jewish workers in Chelmno. The rest had been killed. The corpses were buried in a pile of sand. After the furnaces became operational, the bodies were burnt.

The workers were given 200 grams (7oz) of bread a day, some coffee in the morning, and one half litres (1 pint) of soup for dinner. Only after the first transport had arrived, did we get any blankets. We were constantly beaten during work. They hit us with their hands or spades.

Obviously blows from a spade resulted in death or mutilation, which actually equalled death, as those unable to work were finished up. The Germans killed in the following way: they called a Jew named Moniek Reich, who had to remove the shackles from those to be killed. Then they ordered them to lie on the ground and shot them in the back of the head.

The first transport came at the beginning of April from Lodz. In the morning Bothmann ordered the Hauskommando out of the granary. We were ordered to move baggage that had been unloaded near the narrow – gauge railroad track, in the place where it met the road.

The prisoners were already locked in the church. We carried their belongings to the park, where two barracks had been built, one larger than the other. The confiscated clothes were sorted in the smaller building.

Suitcases were put on one side and the sorted items on the other. The belongings were sorted by the Hauskommando. The most valuable items, new suits etc were kept in the smaller building.

Valuables were given to Burmeister. The transported prisoners were taken to the woods by trucks at six in the morning. But before that the Waldkommando consisting of about 30 people, had already left for the woods. The Jews did not expect any danger on the way. Three trucks transported prisoners to the woods, they were not allowed to take any baggage.

In the evening fellow prisoners from the Waldkommando told us what had happened in the woods. After the trucks arrived, the Jews were ordered to go to one of the barracks in the woods.

The Germans told them to take off their clothes and put them in a separate pile, because they would put them back on after bathing. The underwear also had to be removed.

Women could leave their panties on. Signs on the walls of the barracks read, “to the bathhouse,” and “to the doctor.” The Jews were driven out of the barracks and loaded into a van of a special type.

If they refused to get in, the Germans used force. There were three vans: larger one and two smaller ones. The larger van could hold up to 170 people, while the smaller ones, 100-120.

The van doors were locked with a bolt and a padlock. Then the engine was started. The exhaust fumes entered the interior of the van and suffocated those inside. The exhaust pipe went from the engine along the chassis and into the van, through a hole in the car’s floor, which was covered with a perforated sheet of metal.

The hole was located more or less in the middle of the chassis. The van’s floor was also covered with a wooden grate, just like the one in the bathhouse. This was to prevent the prisoners from clogging the exhaust pipe.

The vehicles were specially adapted vans. On one of them, under a new coat of paint, one could see a trade name. I cannot remember the name, but it started with the word “Otto.”

I do not know the make of the engine. The chauffeurs were Burstinger, Laabs and Gielov. Shouting and banging on the door lasted about four minutes. The van was not moving at that time.

After the shouting faded, the vehicle started moving in the direction of the crematoriums. When the van reached its destination, it’s door was unlocked to let the fumes out. Then two Jews went inside and threw out the bodies.

The gas coming out had all the characteristics of the exhaust fumes (colour and smell) I cannot be mistaken here. The corpses, having been searched through, were placed in the furnace.

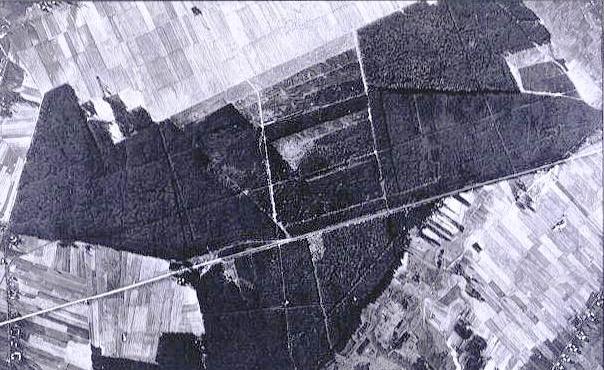

Both crematoriums were built in the same clearing in the woods, several metres from each other. They were located at the entrance of the clearing and vehicles drove past them when they arrived at the place.

However, the furnaces were covered with branches, so they would not be noticed. The corpses were searched through by a Jew called Vidland, who took off rings and pulled out gold teeth. He was supervised by Piller. Each furnace was operated by 12 Jewish workers, who placed the corpses between layers of chipped wood. Before setting them on fire, gasoline was poured over the pile of bodies.

The capacity of one furnace was more or less the same as one van. Runge operated one crematorium and Kretschmer the other. Lenz was their superior. It took approximately one hour for the corpses to burn. Then a new pile of bodies were added.

There were a few instances of unintended self-incineration: a Jew trying to set fire to a pile of bodies died in the flames himself. The bones were ground with the use of a hand-operated grinder on a cement surface near the woods. I did not see any grinding-machine.

The ground bones were carried out of the woods, more or less every second night, together with the ash. I cannot remember the name of the gendarme supervising the Jewish workers grinding bones.

The Jews clothes were stored in the other barracks in the woods. They had to be carried to the barracks rapidly before another truck arrived. (Here, the witness was shown a van found in the Ostrowski’s factory in Kolo). This is the van used in Chelmno for gassing. This is the vehicle I mentioned in my testimony with the word “Otto” on its door.

The witness was also shown photographs on cards number 155 and 157 (1) and (2). The photographs show Bolman, a sentry who did not generally hurt or persecute Jews.

Photograph number 3 shows Schneider, a sentry who beat and abused Jews. He mocked us saying that the following day there would be some good news for us, which later always appeared to be death.

Photograph number 4 shows Muller, a sentry who allegedly died in Warsaw. In the photograph number 5 there is a sentry whose name I cannot remember. He treated us very badly. Photograph number 6 shows a sentry whose name I cannot remember either. He also treated us very badly.

Photograph number 7 shows a sentry called Ruwenach. This one was good. He made it easier for Finkelstein, a Jew, to escape. But the Jew was then caught outside the camp and killed.

Photograph number 8 shows one of the cruellest Germans. He was a sadist, who killed many Jews with his one hands. Photograph number 9 shows a sentry named Daniel. He also treated us badly, however, not the same degree as Blei.

Photograph number 10 shows Hutner, a sentry from Leipzig. He was very good to us. He tried to make our lives easier. When there were no Gestapo officers he let us take a walk in the garden. He would even go with us to pick raspberries.

Once while we were picking the fruit, the commandant arrived. Then Hutner hid us in the raspberry bushes and he kept on with his sentry duty. He was very humane. He gave us bread secretly. He never beat us. He told us who was going to be killed next.

He comforted us saying that they might not have enough time to kill us. He even brought us newspapers. He told us how it had been in 1942, as he had been in Chelmno then. He did not say how many Jews were annihilated in Chelmno in 1942 (the witness was shown photograph number 4 on card 102 of the files). I cannot recognise anybody in the photo shown.

Transports arrived in Chelmno every second day. Each transport carried from 700 to 1,000 people. I estimate that in 1944 alone 15,000 Jews were brought to Chelmno. However, I did not count them – my assumption is based on what the gendarmes had said before the transports arrived. That is why I claimed that in 1944 15,000 Jews were killed in Chelmno.

The transports arrived for two months. All of them with no exception first went to the ghetto and only then were they directed to Chelmno. This is how Jews from abroad arrived.

There were Jews from France, Czechoslovakia, the Reich (Berlin, Vienna, Hamburg) and even Jewish citizens of England. One Jewish Englishman named Alex worked in the Waldkommando for some time. I cannot remember the last names of any of the foreign Jews.

I can only remember there was Dr Proskauer a Jew from Hamburg. As far as Polish Jews are concerned I can remember the following names: Icek Koltan, Mojsze Koltun, Henryk Oberfest and his brother, Henoch Erlich, Wojek Erlich, Mordka Mordkiewicz (Mordkowicz) and Abram Mordkiewicz (Mordkowicz), Szmul Paschwalski (Pasalski), Dr Wajs (9 Zawiszy St) with his family, Dr Miller from Lodz and Mandelsohn (brought by Kramp).

The camp was liquidated and the barracks dismantled. Machines for shredding clothes and underwear were sent back. The furnaces were also dismantled. In the granary there were still 87 Jewish workers. Those were tailors and shoemakers. They lived upstairs. The number of workers decreased and finally there were 47 of them left – 22 tailors and 25 courtyard workers.

Bothmann wanted to kill me several times, but Hafele liked me and this partly helped save my life. While the clothes were being sorted, high ranking SS-men came and chose something for themselves. The chosen items were packed and carried to their apartments.

When the Soviet army was advancing quickly, one night we were ordered to leave the granary in groups of five. I cannot remember the date. The area was lit with car headlights.

I went outside in the first group of five. Lenz ordered us to lie down on the ground. He shot everybody in the back of the head. I lost consciousness and regained it when there was no one around.

All the SS men were shooting inside the granary. I crawled to the car lighting the spot and broke both headlights. Under the cover of darkness I managed to run away. The wound was not deadly. The bullet went through the neck and mouth and pierced the nose and then went out.

I hid in Wieczorek’s barn (he knew about it). They did not find me. Later I learned that while killing the Jews, Lenz and Haase also died (I saw their bodies). When the two went inside, the Jews hung one of them and shot the other one with his own weapon. Apart from me, one other person managed to save his life that night. It was Max Zurawski, who pushed his way past the gendarmes and escaped.

I did not see any Poles transported to Chelmno in 1944, Lenz told two workers to exhume the corpses of two priests buried in the woods. They could have been there for a month. They were dressed in cassocks. Their bodies were burnt. I do not know anything about executions carried out by firing squad at night. Nobody has ever told me whether the camp was prepared for killing Poles.

I did not give any valuables to the girls working in the kitchen. We, the Jewish workers did not have any valuables. We could not get them from the Jews transported to Chelmno, as we did not have any contact with them.

Finkelstein, whom I have already mentioned in my testimony had to throw his own sister into flames. She regained consciousness and shouted, “You murderer, why are you throwing me into the furnace? I’m still alive.”

Finkelstein was shot dead by Sliwke while trying to escape. From time to time Bothmann organised some penalty exercises for entertainment. Lowering the finger meant “drop down.” Lifting the finger meant “Get up!”

After such penalty exercises which sometimes lasted 1.5 hours we all cried. The chauffeur of the truck which is parked in the former Ostrowski’s factory in Kolo, was Burstinger. The prison cell floors were sprinkled with chlorine. But at the site of executions, chlorine was not used.

In 1942 six Jews managed to escape. Some of them were killed, but some survived. One of them was brought back to Chelmno in 1944. He warned that all the prisoners would be gassed. The other Jews being transported did not believe him, assuming that he must have gone mad.

The Jew jumped out of a church window and threw himself at Schneider, a gendarme, trying to kill him. Schneider shot him dead. I did not see or hear about Jews protesting during transports. Before the Uprising 30 gendarmes were sent to Warsaw. Apart from the Sonderkommando members mentioned in my testimony, I can remember the following names:

In the Sonderkommando Kulmhof there were 15 Gestapo officers:

Bothmann, Piller, Lenz, Runge, Kretschmer, Hafele, Sommer, Gorlich, Laabs, Burstinger, Gielow, Richter, Burmeister, Schmidt and one more whose name I cannot recall.

From the time the transports started arriving there were no more cases of fainting from hunger, although the amount of food was still insufficient. I did not hear about Jews cutting off human flesh, roasting it and eating it.

I do not know the addresses of the Gestapo officers.

Here the protocol was closed and, after being read, signed.

(signature) Srebrnik, Szymon

(signature) Bednarz

District Court Examining Judge

* Note Szymon Zanger Srebrnik died on Sept 18, 2006

Sources: Chelmno Witnesses Speak - The District Museum Konin 2004 Lodz Polish State Archives (Naczelna Dyrekcja Archiwów Państwowych) Holocaust Historical Society The Jerusalem Post

Copyright 2008 Chris Webb H.E.A.R.T

|