Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| |||

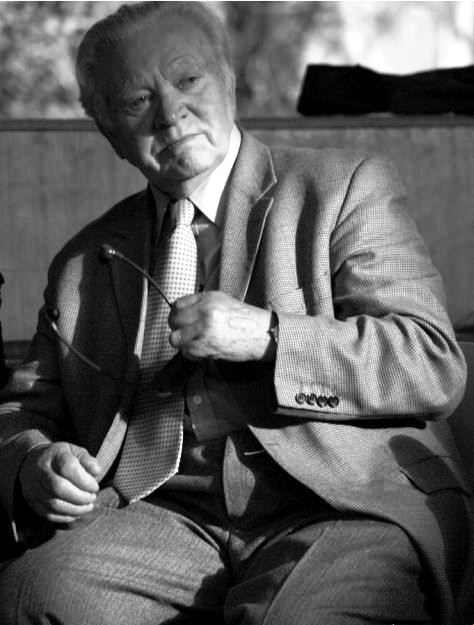

Henryk Mandelbaum Speaks on the Gas Chambers at Auschwitz

Henryk Mandelbaum was born on 15 December 1922 in Olkusz, Poland to a poor Polish –Jewish family. His entire family was forced to move to the Dabrowa Gornicza ghetto in 1940. His parents were later transferred to the ghetto in Sosnowiec.

Henryk Mandelbaum arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau on 22 April 1944, on a transport from Sosnowiec, he was tattooed with the number 181970 and was after a period in Quarantine he was selected to work as a member of the Jewish Sonderkommando that slaved in the crematoriums of the death camp.

In 1945 he was able to escape from one of the death marches in the vicinity of Jastrzebia Zdroj. His sister was the only other survivor from among the Mandelbaum family.

He remembers those dark and terrible times at the site of the mass murders in conversation with Stanislav Motl in 2008. These are Henryk Mandelbaum’s own words:

“Right now we’re in the world’s largest cemetery. This is Crematorium Number 2, Number 3 is over there about 100 metres away. They are the former twins, which back then used to be the new generation of crematoria. They looked like small chateaux. Nobody would think people were gassed and murdered there. The young, the elderly, disabled people, simply everybody, all living people.

They would travel in sealed wagons for 4 days, sometimes even 5 days. It was hot, they had no water, only the things they bought along. Some of them had canned herrings with them. So by the time they got off the train, they almost weren’t like humans any more. When we spoke to them, they were exhausted from the trip.

Suppose I tell you – you aren’t going to a shower. I’m asking you what does it change? You’re not going to survive and neither am I, because there is no chance anyone gets out of here. You have to realise that. You think I choose not to say it? You know I would have loved to. I would have loved to give them my heart – but there was no way, no use. Of course, if I could have changed anything, we would have helped them.

They’d just walked down. The whole thing was located underground. They’d undress. There were the two shower rooms, that is the two gas chambers. In the changing room you had hangers and benches, so they didn’t see through it, they didn’t know. The first ones who entered had to undress, to go to the showers and they’d hang their clothes on the hangers and enter the shower room with their toothbrush, toothpaste, towel and soap and their valuables.

And there were two of these showers, as you can see here underground – so there were two gas chambers in fact. Divided in two parts, each chamber had these two holes. The chambers looked like this – they’d see these showers , so at first they didn’t know and they thought they were real, but maybe a quarter of them were inside and others kept coming in – they’d start feeling something wasn’t quite right, because so many people going to the shower was strange. So they’d try to get out. But the SS men would beat them over the head with these sticks and push them back in.

The gas worked like this, when there were a lot of people inside, humidity increased in the showers because of the breathing and the Zyklon dissolved with the humidity. 12 thousand of them I think it was.

They’d gas them and burn them. In the beginning they used to burn them in Crematorium 1 in Auschwitz, a primitive one. But then neither crematorium 1 nor 4 or 5 could keep up with the influx of transports. They had scheduled arrivals from all around Europe, right! So they had to build crematoria 2 and 3 with 15 furnaces each.

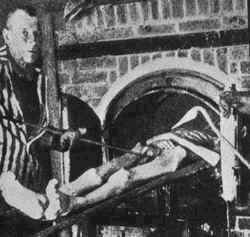

The sight after the gas chamber door opened was gruesome. I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy or anybody. The people went into convulsions. They had bloody swellings, you could see faeces in the back. They must have died in terrible, horrible pain. Once they were gassed, we the Sonderkommando had to pull them out of the gas chambers. But before burning them , we had to look for gold teeth in their mouths. We had these dental pliers that we had to use. We had to see if something was hidden in noses, ears, with women we had to look in vaginas, to see if they hid anything. And then we had to shave their hair before they were cremated.

We’d lay the dead men on stretchers which would be put on these conveyors. And these conveyers were moveable. You’d do it this way. Two guys pushed the body into the furnace. A third guy had a fork made of some armament steel and further helped to push the body in the crotch so it fitted inside the furnace without the legs hanging out, otherwise you wouldn’t be able to close the door.

One could fit three corpses in the furnace and there were fifteen furnaces here, which amounts to forty-five gassed corpses. No matter the age: men, women, retired people. You were supposed to burn the forty-five for half an hour, but it really took somewhere between 20 and 30 minutes. Forty-five in half an hour and the same for Crematorium 3, the twin. That is ninety in an hour right? Multiplied by eight that is seven hundred and twenty in eight hours, in these two crematoria. And that is the way it worked. The transports kept arriving. They’d gas them and we burned the corpses. We’d burn them but we were dead men ourselves- the ‘living dead’.

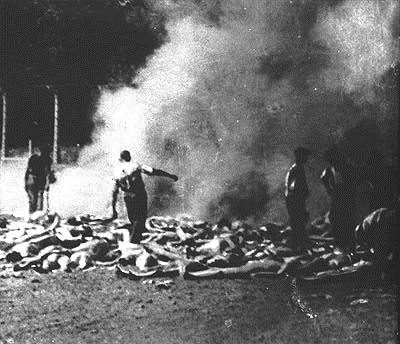

Over here, there were a lot of dead men, gassed but so swollen too. Terrible sight, but there they lay, they couldn’t burn them, but the chamber had to be emptied because the transports kept arriving. They didn’t want the people to see them, they had to keep the place tidy. So for the time being they put them behind the crematorium and there they lay overnight and the following day too.

And I saw them in those ditches, there was smoke and something was on fire. They’d bring poles made from young trees, 80 or 70 centimetres cut into four and also conifer branches from spruce trees in the woods. On top of this we’d lay the dead men. Then another layer and so forth. They burned fast but just the legs, the arms, the heads and parts of the hips. The thighs wouldn’t burn because there is a lot of flesh inside, so you need a high temperature.

We had these hooks from the armoury made from coarse wire, so we’d drive them into the thighs and pull them into another ditch. The other reason why the bodies wouldn’t burn is because they were piled up on top of one another and there wasn’t enough air coming from the bottom.

Every ditch had in the corners these holes, 40 by 40 or 30 by 30 and 70 or 80 centimetres deep. A normal person didn’t burn well inside these layers. And the fat of the gassed people that wouldn’t burn flowed into these holes. Because if you pour petrol on something and set it on fire it burns right away. But oil doesn’t burn as fast. So the fat would flow into those holes and when they were about three quarters full we’d scoop out the fat with these types of mugs and pour it over the dead men, so that the fire would flair up and the corpses would burn faster.

The smell had to be appalling – well, it was burning flesh. Just imagine we worked in those ditches. The wind would start blowing against us, so our eyes were streaming. If I drank a litre of water, I’d lose a litre and a half, when my eyes were streaming. We worked without masks. We never had breaks, if it rained. Like I’m saying we were like those dead guys, except we were alive, for the time being anyway. Over there, there were two ditches, about 30 metres from here and we had to pull those dead men by their arms into those ditches.

But we had no chance, we’d just wait. One second with the Sonderkommando was like a minute. One minute seemed like an hour, and an hour, that was a day and a day became a week. We’d wait for help to come from above, from the right or left side, from the front or from the back, but nobody came, so sadly we had to keep working like this, while the transports kept arriving and they kept gassing and killing the people and we had to keep burning them.

Oh God, those people were very religious. They prayed, they scratched words on the walls of the gas chambers with their fingernails. And who could help them? They couldn’t help themselves, we couldn’t help them either, nobody could. And nobody helped us either. And where was God? I’m asking where was God? Why, where was he? See I say I can’t remain a religious person after all I’ve seen. Well, where is he?

Alright, if 10, 20, 30,40, 50 people died, but there were millions. Nobody knows exactly, because the exact figures aren’t known. They say 2 million 300 thousand or many more, just imagine it, all those innocent people. They hadn’t stolen or killed but they lost their lives in such a disgraceful way.

While working I took a vow that if ever I survived this drama I would speak about what I saw with my eyes, so the whole world would know. Because as long as the world exists, whether it be for a hundred thousand or even two million years - nobody knows exactly, do they? Nothing similar has ever happened – the gas chambers, people being gassed.

Alright my dear friends: just behold the peace around here. I’m repeating myself, but the trees, if only those trees could talk. If you look through the trees, you can see that area?

From this tree to the first one, that’s the area where we’d bury the young girls, the women like Venuses, six at a time, between those trees and young men too, the Appollos, we’d drag them and watch them and our hearts would beat like this”.

Henryk Mandelbaum died, 6 months after this interview, on 17 June 2008 in Bytom, Poland. He was eighty six years old.

Sources:

Biokiss Film and National Geographic Television International The Auschwitz Chronicle – Danuta Czech The Auschwitz Museum Holocaust Historical Society

Copyright. Chris Webb and Hans Zimmerman H.E.A.R.T 2013

|