Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| |||||||

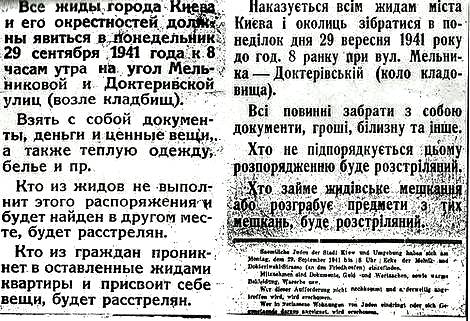

Yakov KaperHis Account of Life in Kiev 48 Melnikova - Syrets Camp – Babi Yar Selected Extracts from the Thorny Road

Part 4 – Babi Yar Ravine

Before we were sent to Babi Yar we noticed that opposite the exit from the Syrets camp a high fence had appeared. We did not understand what it was covering. As soon as we approached the camp gates we were ordered to take our footwear off. We thought it was our last stop. Here policemen and the Germans were not like those in the camp, they were even worse monsters with awful bandit eyes, but it was all the same for us, we didn’t bother them.

At last the command was given and we went out. We were escorted by two soldiers with automatic guns on both sides even though we did not have far to go. Along the road we found ourselves near an earthen rampart and in the distance I noticed a house or a hut. At the entrance there was a skull with crossbones, but it was not a drawing like on electrical boxes but a real human skull and bones.

It became clear that there was no way back from here. We were led further and we found ourselves in a ravine and inside there was smooth ground. I didn’t understand how they came there in cars but it was evident that this was a road and that some gaswagens had been there.

We were ordered to sit down on the ground, we heard a lot of noise and cries over the precipice. We did not know what was going on, at last a young officer, who I think was one of the bigger bosses appeared. He was yelling louder than anybody else and ordered groups of people in fives to come forward.

So, one of those German bandits went, took five of us and we were led behind the fence that was made of twigs and sticks. We didn’t know what was going on behind that fence. The one thing that calmed us down a little was that no shootings were heard there, which meant that they would not shoot us immediately. If they killed us in a gaswagen, they would have killed us all at the same time.

Soon the same fascist came again and took five more people: I was sitting and did not know what to think. I must say, I didn’t think about much at all since there was, seemingly no options other than death, so whatever would be would be.

At last my turn came, I was led away. As soon as I found myself behind the camouflaged rampart I saw the panorama that I would remember till the last day of my life. The corpses were accurately laid out – later I learned that the furnaces had been prepared to burn the corpses. I cried out, “That’s enough I don’t want to live any longer, shoot me now.”

At that moment the biggest boss, a German ran up to me, later I learned that his name was Topaide, he struck me so hard in the face that he rattled my lower jaw. I could neither cry nor talk. One of the Germans pulled me towards another one who was sitting on a small stool. There were chains and a rail lying there, he put the clamps on my ankles then the chain. He inserted rivets and hammered then on the rail.

I started guessing where we had ended up and what we would be doing, he ordered me to sit there where other chained prisoners were already sitting. My mouth bled and I couldn’t feel my teeth nor move my tongue. I tried to fix my jaw with my hands.

We all were sitting and waiting until all of us were chained and then dinner was announced. All those working stopped their work and came to the place where we were sitting. When all of them were lined up, Topaide ordered the guards to check the chains on the prisoner’s ankles. They were checked three times a day.

Everybody in the line was checked and then we were ordered to get food. There stood thermoses with soup, each prisoner came up and got a slice of bread and a scoop of soup. I couldn’t eat anything. Philip Vilkes came up to me and I gave him my portion. He exclaimed that this is the end and there was no hope anymore.

When dinner was over each went to his work. The newcomers were also assigned to work: I together with ten other prisoners joined the team that was called the outgoing team, though there was no going out there. There where we had seen the camouflaged fence was also a ravine, but it was almost on the road, when the war began people dug an anti-tank trench and in it were the corpses of military men and commanders mainly.

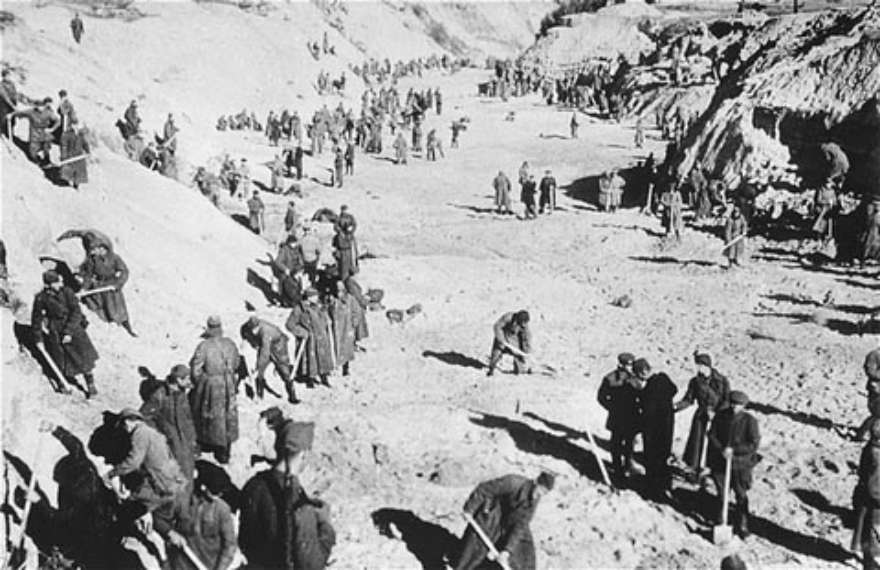

On one side, a furnace was being erected, first they brought stones taken from the Jewish cemetery, the tombstones bore the dates of those buried in the cemetery. Long railway rails were put on those stones, then iron fences also removed from the cemetery and then some logs with a little room in between to let air through when they started burning.

Topaide headed the work of those making the furnaces, he ran from one place to another without a minute’s rest: he quickly gave orders and went on running. The main work was in Babi Yar but he also ran over to us in the anti-tank trench. When everything was ready we were ordered to pull the corpses out and put them on the furnaces. For this special tools were prepared, there was a handle in the form a ring and a rod 50-60 centimetres long with a hook sharpened end.

We were shown how to insert this hook under the chin and pull the corpse out, all this work was done very quickly, every five prisoners were supervised by a German with a whip. If he struck he could kill. And all the time we heard the cries “Schnell.” We pulled out the corpse and brought it up to the ground, there other people picked it up, they opened the mouth first, if there were gold teeth, they were pulled out.

Then they took off the footwear and then accurately laid it by the head. Several layers of corpses were put together and then all were doused with oil, logs were laid and then more corpses and so forth. So at the end it was 2.5 or 3 metres in height.

In order to put corpses on the top: a special scaffolding was erected. Thus, during the day we prepared for each furnace about two and a half to three thousand corpses. When everything was ready once again oil was poured over everything and the furnace was lit with torches. At first the bright flame lit the whole ravine, but gradually the black smoke covered the flame, the air filled with smoke and the sweetish smell of burning. It became impossible to breathe, at first the hair was burning then the bodies caught fire.

Germans who were with us there also couldn’t breathe and were very often replaced. They also carried flasks with water and they drank it constantly. At the same time another furnace was being prepared in another place, and while one furnace was burning down another was lit.

Bones remained almost untouched though they were in the fire, they were gathered and put on a special ground lain with granite plates, a special team was crushing those bones into small pieces with special mortars. Then they were sieved and big bones were again crushed then mixed with sand and were scattered on the road.

When the working day was over we were lined up and went over to the others who worked in Babi Yar, they were standing in line and were waiting for us. Again the chains were checked and afterwards we were given a scoop of soup and went to the barracks. I saw this enormous barracks for the first time. There were all our mates from the Syrets camp that had been taken earlier. Each had his place - I didn’t pay attention to finding a place on the bunk beds. All the beds were already occupied and many of the prisoners were lying under the beds.

I also went to sleep underneath a bunk bed on bare ground, near me was Lenya Kadomsky and Volodya Kuklya, our place was not far from the door and at least the air was a bit better there. In the dug-out there was ventilation for fresh air but the door was made of welded iron rods. That’s why I chose the place there. I gave my supper to the other prisoners since after the blow of that bandit Topaide I couldn’t eat. I lay thinking how unlucky we all were and thus I fell asleep.

Suddenly I heard some noise and didn’t understand that it was time to get up and though it was still dark but everybody was preparing to leave. Going out of the barracks I noticed what I had not noticed before; it was necessary to go down or up 5 or 6 steps to come in or out of the barracks. Opposite the exit from the barracks, a watchtower was erected and there were always Germans with machine-guns aimed at the door of our barracks.

During line-up the chains were checked again, I had already managed to tie them up with rope, as everyone did. One end of the rope was tied to the middle of the chain, the other to the upper button of the trousers. It made it easier to walk since the chain was not hanging loose. After inspection, we were given our breakfast a scoop of soup and a piece of bread, the food here was better than in the Syrets camp. After breakfast they counted off 70 or 80 people and sent them to the anti-tank trench and the rest were sent down to the ravine. I was also sent there.

The work was the same as in the first trench but here the corpses were pulled out with small hooks and it was not far to pull them. The rest was still done by the others. Here in Babi Yar it was much harder to pull out the corpses. True the upper corpses, obviously, recently shot were easily drawn out. But those on the bottom, shot in 1941 were lying intertwined, some of them were shot and others were not touched by the bullets. They were lying all together and it was next to impossible to pull out the corpse.

Many times the corpses were drawn into two and that’s why they were pulled out with big hooks. Workers tried to pull a hook under a rib and then several men having caught at the hook-handle managed to pull the corpse out. Then the corpse was pulled with small hooks towards the furnace where it was inspected by the team of Goldsucher- Gold searchers. Gold teeth, rings, ear-rings and other jewels were taken out and the corpses were put onto the furnace.

All this work was done under the strict supervision of the Germans. As we were so to say naked and barefoot we managed to pull something over ourselves. It was either a coat or a pair of boots. They could be dried a bit and then put on. We didn’t pay any attention to the fact that it all smelled awfully.

All this time we did not wash our hands but still ate with them, the work lasted from morning till dark with a short break for dinner, any violation of the order was punished on the spot with shooting and burning on the stake. It was necessary to work without saying a word to anyone, if they noticed anybody talking they shot them at once.

All of us worked in the ravine, together with us were Germans who supervised us with a whip and an open holster for a pistol, they changed every two hours, the main guards were on the slopes of the ravine with their machine-guns ready. Among our captives there were also traitors, as we learned. Such a traitor was among us in our dug-out – he was also in chains – his name was Nikon. He was brought from Belaya Tserkva region where he had served as a policeman and we did not know how he got to our dug-out.

There could be some more, that’s why everyone kept to themselves and spoke only in whispers. Still some people agreed and started digging a tunnel in the barracks. They could not manage to do it within one night since they had neither spades nor any other tools and they were digging with their hands.

They camouflaged the hole and put the dirt under the different bunk beds, the Germans did not enter the barracks usually, but Nikon informed them that there was an escape attempt with sixteen participants. They were all shot and we were ordered to put them onto the furnace.

Our team in charge of burning corpses contained 330 persons. Each day – three times our chains were checked and they reported to Topaide with humour that in the heavenly team there were so many figures. In German the word figure means corpse, they reported it and laughed since they considered us “live corpses.”

Still, once there was a miracle about which we couldn’t expect, we worked in groups: in one of the groups our friend Fedor Savertanny asked permission to satisfy his personal needs a few steps away from the rest. Since there were no toilets the German guarding this group permitted him to go. At this moment some bosses arrived and the guard must have forgotten that he had let the prisoner go. Savertanny used the opportunity of not being observed to remove his chains and dashed for the cemetery and from there he ran away.

When the fascists started searching, it was already late, he had reached the city and managed to hide away, thus Savertanny remained alive, but when it became known that one of the prisoners had run away the work was stopped and they shot fifteen other prisoners and we didn’t know where they had put the guard who had made that mistake.

I believe that there isn’t and cannot be more back-breaking and harder work than that of burning corpses, our life wasn’t worth a nickel, they would shoot anyone for any reason. The only thing that saved us was that they needed us for work.

Everything that was done in Babi Yar was top secret, even for most Germans, when they brought food or something required for burning, like logs or oil, it was brought up to a certain point and nobody was permitted to go beyond it. They must have ordered everything over the phone since the guards brought everything for us on the trucks, so other Germans didn’t know what was going on there.

I think that the dwellers of Kurenevka and other adjoining districts must have guessed what was going on in Babi Yar, from morning till night the sky over Babi Yar was covered with thick black smoke with the smell of burned flesh.

Besides burning the corpses of those shot in 1941, almost every day a gasenwagen came to the ravine with murdered people inside it. It was an awful sight, there were people of different ages and nationalities. Germans opened the door of the gasenwagen and ordered us to unload the corpses and put them into the fire.

Sometimes the gasenwagen arrived and the people inside were murdered only after the arrival. We heard how they cried and knocked on the walls and then gradually everything calmed down. When we put them into the fire the bodies squirmed like live ones and it was impossible to look at them.

Sometimes it happened so that when the gasenwagen arrived at the ravine full of people to be annihilated, the Germans opened it, let them run out, put them in chains and made them work together with us. The work force was scarce. Every day we worked like robots, we were urged on, beaten, covered with sweat and blood.

High bosses came and cried at Topaide, that the work was going very slowly, and the prisoners should be woken earlier and punished more to make us finish quicker. They hurried to hide their traces.

Topaide, in his turn, yelled at the Germans who supervised us, made them beat us to make the work go quicker. He accused them of treating us too cordially. At the line-up Topaide said that “those who work well would be taken to the team which would go with them to Zhytomir, Berdychev or Lvov, the rest would stay here and he pointed to the furnace”.

Though all of us knew that we all would be there where Topaide pointed, we still hoped for some miracle that would keep us alive, there wasn’t a day that passed when five or six people were not shot because of poor work or some other offence.

Once the gaswagen came, there were dead absolutely naked young girls – there were so many of them that one couldn’t guess how they managed to get inside. Many of them had handkerchiefs on their heads. Some of them hid rings, ear-rings and watches under the kerchiefs. I remember that when I carried one of the girls to the furnace a watch fell from under the kerchief where she had hidden it. All the corpses were wet and presented an awful sight: the Germans laughed and said some unseemly expressions.

Once when we were pulling the corpses out something had happened but we couldn’t come up and see, as it turned out one of our prisoners recognised his wife and two children who were killed in 1941. He was not sure until the children were separated from the mother and when she was turned over he recognised the scar on her neck that remained after an operation before the war.

When in the evening he came to the barracks he cried and told that his wife and two daughters of 10 and 12 hadn’t managed to be evacuated and stayed in Kiev. He went to the front from the very first days of the war, got captured and found himself in the camp.

He knew nothing about the fate of his family, and here this hair-raising meeting took place, after this nightmare it was impossible to fall asleep, I was lying and thinking that if we could open the padlock on the barracks door and attack the guards at least some people would escape alive. It would be better than all of us being shot down without any chance to tell the world about the awful things that took place here.

In the morning I had a conversation with Volodya Kuklya and Leonyd Kadomsky who slept nearby, they liked my idea that we should find the key that would match the padlock of our barracks. They promised to do it as they were good at locks.

Kadomsky was a good fitter and Kuklya was a good mechanic-fitter, I also knew what key would match our lock, the lock was a big and heavy padlock, so we agreed to do it and not to tell anybody so as not to be exposed to the Germans.

In Babi Yar in the pockets of corpses, one could find many things, the bottom corpses were absolutely naked, the middle layers were half naked and the top layer corpses were dressed. Once in one of the pockets we found a bottle of wine and we drank it on the spot, the Germans saw it and laughed.

Others found a bottle of eau de Cologne and wanted to drink it but one of them said that it would be better to pour it out in the barracks. So they did it. Sometimes one could find small tools like files, scissors, screw-drivers and others.

Nearly every corpse had keys on him, people locked their flats and apartments and took the keys with them. The keys were different; one could choose what he liked. The work was coming to an end, the Germans were in a hurry and urged us on.

Many of those in our team that burned corpses had already perished, some were shot down: others couldn’t stand it and committed suicide. To replace them, others were brought there every day, the newcomers secretly told us that the front was very near and we also could hear distant sounds of explosions. We kept on trying to survive for another day. Every day more and more people did not come back to the barracks alive.

To bring the keys to the dug-out was very dangerous since it would be clear what it was meant for. Besides, every day while checking our cuffs they always searched our clothes. That’s why I told Kuklya and Kadomsky what key to look for and warned them not to have more than one key in their pockets, so it would not make any noise. I also thought that it was very dangerous.

By the end of the day I found one key that looked like the one we needed. I brought it, the other fellows brought nothing back. Either they were afraid or didn’t find anything and said that there was none that looked like the one we needed.

On the next day I again brought the key, they again brought nothing and the following days again. Almost every day I brought a key and stopped reminding them since I thought that they were afraid and didn’t want to risk it.

When I had several keys that could match, I agreed with Trubakov and Doliner that at the time of giving out meals they would shield me near the door in order that neither the Germans nor the prisoners would notice how I would try the keys in the lock.

During the two days I tried all the keys, one of which matched, I opened the padlock and then locked it back again. So I had the key, all the rest of the keys I tossed down under the bunk beds and this one, I also hid but in another place near where I slept. We didn’t tell anybody about it at the time and kept it secret.

But an extraordinary incident took place, whilst checking the cuffs one of the Germans felt some hard object in the pocket of one of our fellows, he ordered him to turn the pocket out and scissors fell out of it. Topaide started beating him. When asked what he had taken the scissors for he said he wanted to cut his hair but it was not believed. They thought it was to cut the rivets on the chains. He was beaten till he lost consciousness, then he was thrown into the fire. He was still alive and he cried awfully, so he burned in the fire.

After this I thought how much I had risked to find and try the key. The work was coming to an end and some of us were sent along the ravine to the Krillovskaya hospital. There was also another ravine where many people were shot and the same work was to be performed there. But the work there was also coming to an end.

The burning of corpses was finished and we were ordered to remove the camouflaging fences. One part of prisoners was sent to gather the ashes near the furnaces. We put the ashes on the stretchers, mixed it with sand and put it on the road, so as not to leave any traces. Others were sent to erect another furnace here it became obvious, since there were no other corpses, who it was meant for.

We did not know what to do. When we were gathering the ashes with a spade near the furnace, I suddenly noticed golden coins in the form of an ingot. They must have been wrapped into something and got melted together. I put this ingot into my shirt.

So the works in the ravine and connected with building a new furnace came to an end. The team that worked near the Krillovskaya hospital also came back. We were lined up and the Germans were whispering something and looking at the road, they must have been waiting for big bosses.

But there was no car in sight, we stood a bit more, then we were ordered to sit down, there were many guards about , then not to cause any suspicions they ordered two prisoners to boil potatoes, our fellows lit the fire, took two big pots and started boiling potatoes. The Germans got tired of standing near us and they decided to put us in the barracks, and then we got to know everything. There was a fellow among us, Steyuk Yakov, who was an interpreter.

When they were coming from the Krillovskaya hospital one of the guards said to Steyuk quietly that the following day would be our last. Steyuk told us secretly in the barracks about this talk with the guard. Someone else that the Germans wanted to wait until the higher-ups were present and so decided to wait till the next day.

When we found out that it was already our last hour I decided to tell Budnik about the key. Budnik and Steyuk came up to me and asked if I had tried the key and if it worked. I gave the key to them and we agreed that later on that night we would remove our chains, open the door and run away. In order to escape we had to make sure that the Germans did not hear anything when we were removing our chains.

As we were helping each other get the chains off, I saw Germans approaching our barracks and heard one of them open the door. We felt cold and I thought that this was it. The lock was opened and four of them brought in two big pots of potatoes. They decided to feed us before the death, we thanked them and started taking potatoes but we were ready for escape.

It was necessary to tell the other prisoners of our plan, some of them took potatoes and went to their places and laid down to rest. I thought that nobody would be able to sleep and tried to figure out for myself what I could do to make it to midnight.

In Babi Yar time was moving slowly that night, I remember how usually we were so tired that we could hardly lay down before it was time to get up. At last we started to move and talk, I also got up, but saw people were afraid to thake their cuffs off. I noticed a big pair of pincers I took them and broke the rivets so that the clamps fell off together with the chains Others also started removing their chains.

I helped Ostrovsky to remove his chains since he was only able to work with one hand, he had wanted to help one of his fellow prisoners one time put the hook into a corpse. He put his hand down and the other prisoner accidentally punched his hand.

The inflammation had started probably due to his poor condition the hand was swollen and looked gangrenous. I unchained him and then helped Vilkes. When I came up to Budnik and offered him my help, he said, “Yasha I want to live another half hour.” I removed his chains and told him he could live as long as he wishes, I also unchained Vanya Kusnetsov and helped many others. Thus almost everybody was unchained except those who were sleeping and those who we could not trust.

At this time others were occupied with the padlock, Volodya Kuklya tried opening the lock. Very carefully he inserted the key into the lock and tried to open it, but it would not go. It was a big padlock and it was necessary to press harder. Volodya was standing inside the barracks having put his outstretched hand through the barred door all the while his hands and legs trembling. He had hardly managed to turn the key once and pull it out.

The guards heard the lock clank, Kuklya ran off quickly, the Germans came up to the door, pointed his flashlight on the padlock, it was in its place. He tried the door it was still closed. When Kuklya was running away from the door he tripped over the pots and fell down. The German cried out, “What’s the matter in the barracks?” Steyuk said, “That we were fighting over potatoes.”

The German laughed out loud and told another guard going along the upper level of the barracks, “they are fighting over potatoes, not knowing that tomorrow they will need nothing.”

We decided to try to open the lock again after the changing of the guard, after the switch they stood calmly talking, not suspecting what was going on. When everything calmed down Kuklya approached the lock, inserted the key and silently turned it for the second time. The lock opened, Kuklya removed the key and the opened lock remained hanging on the door.

When everything with the lock and the chains was ready we came up to the door very quietly, Philip Vilkes quietly removed the lock and cried out, “Run for your lives, comrades!”

The guards got frightened at first but after several minutes the guard standing on the watch tower started shooting with the machine-gun. The Germans who stood near our barracks were silent and I thought they had been mowed down by the gunfire. But our comrades who ran out first told us later that they had attacked the Germans. There was a fight and the machine-gun was aimed at the open doors.

But people ran outside oblivious to this fact, they were shot down dead while others ran after them crying out, “Hurrah!” At last the Germans understood what was happening and all the guards got to their feet.

They started pursuing us on cars, motorcycles and with dogs, the ravine was lit with flares, the shooting remained in front of us, the pursuers did not know where to aim their shooting since all the prisoners scattered in different directions. Some of them ran off with a chain still clamped to one leg, since they had no time to unchain it.

The majority of the prisoners were running along the ravine, some of them went up the slope along the highway towards the Syrets camp and further on to the Bolshevikplant. Those who ran along the ravine had only one option towards Kurenevka, at dawn as the shooting continued, one could hear cries, cursing and the barking of dogs in the distance. The Germans who were pursuing us went down to the bottom of the ravine.

With luck, since we had been running without stopping, by the time they closed off the ravine everybody had already managed to escape. We tried to scatter, tragically only a few people managed to escape, in fact out of all the prisoners only eighteen survived.

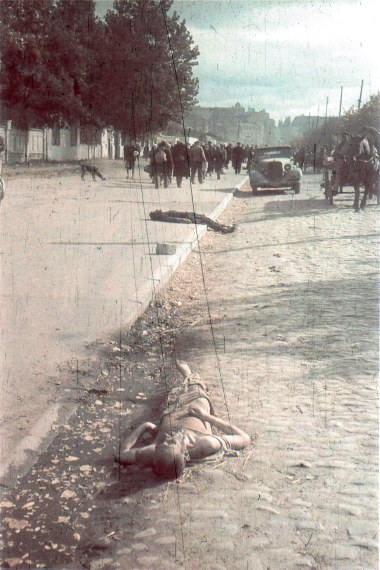

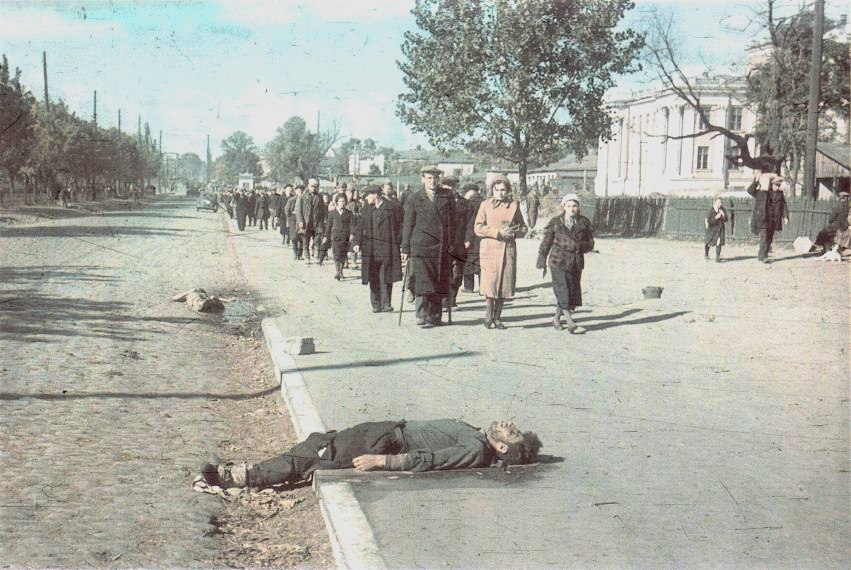

Sources: The Thorny Road by Yakov Kaper Photographs and Map of Kiev from the Chris Webb Archive and other private collections

Copyright Chris Webb H.E.A.R.T 2010

|