Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| ||||||

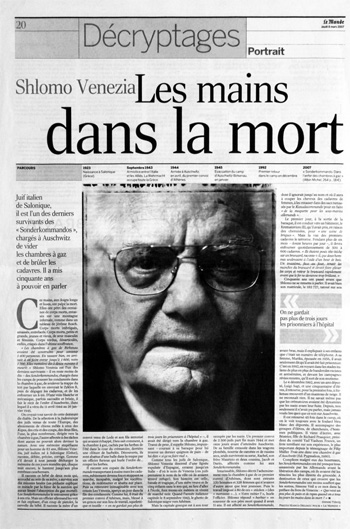

Shlomo Venezia Selected Extracts from Inside the Gas Chambers Auschwitz – Birkenau – Sonderkommando Hell

Shlomo Venezia was deported to Auschwitz – Birkenau from Athens, Greece and he arrived on the 11 April 1944. He was selected to work in the Sonderkommando, at the heart of the empire of death.

Members of the Sonderkommando who worked in the gas chambers and crematoria were murdered after a few months and replaced with others forced to carry out the Nazis evil crimes, but Shlomo managed to join with other prisoners during the evacuation and subsequent “Death March” away from Auschwitz – Birkenau in January 1945.

The following are selected extracts from his book – Inside the Gas Chambers

Arrival at Auschwitz – Birkenau

The train hadn’t blown its whistle when the transport had stopped en-route. So when I heard that peculiar whistle and felt the train suddenly braking, I immediately realised that the convoy had finally reached its destination.

The doors opened onto the Judenrampe, just opposite the potato sheds, my first feeling was a sense of relief, I didn’t know how much longer it would have been possible to survive in this train, without anything left to eat, without any space, air, or toilet facilities.

As soon as the train stopped, the SS opened the doors of the carriage and started yelling “Alle runter!” Alle runter!” (Everyone out) We saw men in uniform pointing their sub-machine guns, and Alsatians barking at us.

Everyone was in a stupor, numb after the journey- and all of a sudden, fierce yells and a whole infernal din to throw us off our guard, and prevent us knowing what was going on.

I happened to be near the door, so I was among the first to climb out, I wanted to stay near the door to help my mother get out. We had to jump for it, as the carriage was high and the terrain was sloping. My mother wasn’t that old, but I knew the journey had worn her out and I wanted to help her.

While I was waiting for her, a German came up behind and struck me two heavy blows on the back of my neck with his stick. He lashed out with such force I thought he’d split my skull. I instinctively placed both my hands on my head to protect myself.

Seeing that he was going to start hitting me again, I ran off to join the others in the queue. Our captors started hitting people as soon as we arrived, to vent their hatred, out of cruelty, and also so that we’d lose our bearings and obey out of fear, without making problems for them.

So that’s what I did, and when I turned around to try to find my mother, she wasn’t there anymore. I never saw her again, she wasn’t there, and neither were my two little sisters, Marica and Marta.

According to the Auschwitz Chronicle approximately 2,500 Jewish men, women and children who were arrested in Athens arrive in a RSHA transport from Greece. After the selection, 320 men and 328 women are admitted to the camp, the remaining people, among them 1,067 men are killed in the gas chambers.

How was the selection carried out?

As soon as we jumped out of the train, the Germans, with their whips and blows, made us get into two queues, sending the women and children to one side and all the men, without distinction to the other.

They beckoned us into place: “Manner hier und Frauen hier!” (Men here and women here) We stepped into place like robots, in response to the yells and the orders.

How far away from the women were you? Could you still see them?

To begin with, we could, but the crowd very quickly became so dense, and at the same time so orderly that I rapidly found myself surrounded only by men. Of all the men who’d been on that train, only three hundred and twenty of us were left after the selection.

And did you at least manage to stay with your cousins?

Yes, we stayed together I never saw their father or the others again.

They immediately made us all line up in front of a German officer. Another officer arrived shortly afterwards, I don’t know if it was the famous Dr Mengele, it may have been, but I’m not sure.

The officer barely looked at us and made a gesture with his thumb indicating “Links, rechts” (Left, right) and depending on the direction he sent us, each of us had to go one way or the other.

Did you notice any difference between the people who went to the right and those who went to the left?

No, I didn’t notice: there were young men and old men on both sides. The only significant thing was the obvious imbalance between the numbers of people on both sides.

I found myself on the side where there were fewer people, in the end there were just three hundred and twenty men left. All the others set off, without knowing it, for immediate death in the gas chambers at Birkenau.

My brother and my cousins also ended up on the right side with me, our group was sent on foot to Auschwitz 1.

In your view, how long did the process take, from arrival to the end of selection?

I think it lasted about two hours. Why do I think so? Because it was still daytime when we arrived on the Judenrampe, and the prisoners had already stopped working by the time my group reached Auschwitz 1.

We walked the distance, just over a mile or so, from the Judenrampe to the camp at Auschwitz 1, while the others unsuspectingly headed off for the gas chambers at Birkenau.

I remember that, before entering the Auschwitz 1 main gate, with the inscription “Arbeit Macht Frei (Work makes you free), I noticed a sign placed near the barbed –wire fence. It read: Vorsicht Hochspannung Lebensgefahr, meaning Beware, high tension, danger of death. Once inside, immediately on the left was Block 24; we later discovered that it served as a brothel for the soldiers and a few privileged non-Jews.

After a short period in Quarantine, Shlomo was selected to work in the Crematoriums and Gas Chambers as a member of the Sonderkommando. Shlomo Venezia describes his initial impressions;

My natural curiosity impelled me to go up to the building to try and see through the window what was going on inside. We had been strictly forbidden to do so, but step by step, I edged up to the window. When I got close enough to catch a glimpse, I was left completely paralysed by what I saw. Bodies heaped up, thrown on top of one another, were just lying there.

At around two in the afternoon the Kapo made us go down into the undressing room, the floor was strewn with clothes of every sort. We’d been ordered to use the jackets and shirts to roll the clothes up into little bundles. Then we had to take the bundles and pile them up outside, in front of the stairs. I imagine a truck then came to pick up the packets to take them to the barracks in Kanada.

Later that same day Shlomo Venezia and other members of the Sonderkommando were detailed to the “White House” in Birkenau:

At around five the Kapo again ordered us to assemble, we obviously assumed that at this time in the evening, “assembly” meant we’d finished the laborious day’s work. But unfortunately this wasn’t the case.

We came back out of the Crematorium, but instead of turning right to go back to the barracks, they made us turn left, through the little forest of birches. I’d never seen this kind of tree in Greece, but in Birkenau they were the only trees one saw surrounding the camp.

As we walked along the path, all we could hear was the wind whistling through the silvery leaves. We came to a little house called as I later learned, Bunker 2, or “the White House.”

Just then the murmuring of human voices became more intense.

Can you describe Bunker 2 as you saw it?

It was a small farmhouse with a thatched roof, we were ordered to stand opposite one side of the little house, near the road that ran in front of it. From where we were, we could see nothing, neither on the left nor right.

Dusk was falling; the murmurs had become the distinct sound of people coming towards us. I was curious, as usual, and went across to try to see what was happening.

I saw entire families waiting in front of the cottage; young men, women and children. There must have been two or three hundred of them altogether. I don’t know where they’d come from, but I suppose they’d been deported from a Polish ghetto.

Later on, when I realised the way the extermination system worked, I deduced that these people had been sent to Bunker 2 because the other crematoria were full. This was also why they needed a bigger labour force to do this dirty work.

Did people get undressed in front of the door or in a barrack?

People were forced to get undressed where they were, in front of the door. The children were crying. You could feel the fear and dread; people were really helpless and terrified. The Germans had probably told them they’d be taking a shower and then they’d been given something to eat.

Even if they’d realised what was really going to happen, there wasn’t much they could do; the Germans would have executed on the spot anyone who’d made the least attempt to escape. They’d lost all respect for the human person, but they knew that if they left families together they would avoid having to deal with any acts of desperation.

Finally the people were forced to enter the little house the door was closed, once everyone was inside, a little truck, with the Red Cross sign on its sides, drove up. A rather tall German got out. He went over to a small opening high up on one of the walls of the little house. He had to climb onto a stool to reach it.

He took a can, opened it, and threw the contents in through the little opening. Then he closed the opening and left. The shouts and crying had not stopped, and they redoubled in intensity after a few minutes. This lasted for ten or twelve minutes, then silence.

Meanwhile, we’d been ordered to go around to the back of the house. When we arrived, I noticed a strange gleam coming from that direction. As I went over, I realised that the light was that of a fire burning in the ditches some twenty yards away.

Do you remember what you thought when you saw all that?

It’s difficult to imagine now, but we didn’t think of anything – we couldn’t exchange a single word. Not because it was forbidden, but because we were terror-struck. We had turned into robots, obeying orders while trying not to think, so we could survive for a few hours longer.

Birkenau was a real hell; nobody can understand or grasp the logic of that camp, that’s why I want to tell the story; tell it for as long as I live, but relying only on my memories, on what I am certain that I saw, and nothing else.

So the Germans sent us to the other side of the house, where the ditches were. They ordered us to bring the bodies out of the gas chamber and place them in front of the ditches. I didn’t go into the gas chamber myself, I stayed outside, going back and forth between the Bunker and the ditches.

Other men from the Sonderkommando, more experienced than we were, had the job of laying the bodies out in the ditches in such a way that the fire wouldn’t go out. If the bodies were packed in too densely, the air couldn’t get through and there was a risk that the fire would go out or fade in intensity. That would have made the Kapo’s and the Germans overseeing us furious.

The ditches sloped down, so that, as they burned, the bodies discharged a flow of human fat down the ditch to a corner where a sort of basin had been formed to collect it. When it looked as if the fire might go out, the men had to take some of that liquid fat from the basin, and throw it onto the fire to revive the flames. I saw this only in the ditches of Bunker 2.

After two hours of this particularly taxing and distressing work, we heard the roar of a motorbike. The old hands murmured with terror: “Malahamoves!” That’s when we made the macabre acquaintance of the “Angel of Death.”

That was the Yiddish name given by the prisoners to the dreaded SS man named Moll. No sooner had he put his foot onto the ground then he started to shout like an enraged beast, “Arbeit” – Get working, pigs – “Schweine” – Jews.

Can you describe in detail what happened when each new convoy arrived?

Every time a new convoy arrived, people went in through the big door of the Crematorium and were directed towards the underground staircase that led to the undressing room. There were so many of them that we saw the queue stretching out like a long snake.

As the first of them were entering, the last were still a hundred yards or so behind. After the selection on the ramp, the women, children and old men were sent in first, then, the other men arrived.

In the undressing room, there were coat hooks with numbers all along the wall, as well as little wooden planks on which people could sit to get undressed. To deceive them more effectively the Germans told people to pay particular attention to the numbers, so that they’d be able to find their things more easily when they came out of the “shower.”

After a time, they also added an instruction to use the laces to tie shoes in pairs. In fact, this was to facilitate the process of sorting out when the things arrived at the Kanadakommando. These instructions were generally given by the SS standing guard, but it sometimes happened that a man in the Sonderkommando could speak the language of the deportees and transmit these instructions to them directly.

To calm people down and ensure they’d go through more quickly, without making any fuss, the Germans also promised then they’d have a meal just after “disinfection.” Many of the women hurried up so as to be first in line and get it all over with as quickly as possible – especially as the children were terrified and clung to their mothers. For them, even more than for the others, everything must have been strange, eerie, dark and cold.

Once they had taken off their clothes, the women went into the gas chamber and waited, thinking that they were in a shower, with the shower heads hanging over them. They couldn’t know where they really were. A woman would sometimes be seized by doubt when no water came out and went to see one of the two Germans outside the door. She was immediately beaten and forced to go back in; that took away any desire she might have to ask questions.

Then the men, too, were finally pushed into the gas chamber, the Germans thought that if they made thirty or so strong men go in last, they would be able, with their force, to push the others right in. And indeed, herded by the rain of blows as if they were so many animals, their only option was to push hard to get into the room to avoid the beating.

That’s why I think that many of them were dead or dying even before the gas was released. The German whose job it was to control the whole process often enjoyed making these people, who were about to die, suffer a bit more. While waiting for the arrival of the SS man who was going to release the gas, he amused himself by switching the light on and off to frighten them a little bit more.

When he switched off the light, you could hear a different sound emerging from the gas chamber; the people seemed to be suffocating with anguish, they’d realised they were going to die. Then he’d switch the light back on and you heard a sort of sigh of relief, as if the people thought the operation had been cancelled.

Then, finally, the German bringing the gas would arrive, it took two prisoners from the Sonderkommando to help him lift up the external trapdoor, above the gas chamber, then he introduced Zyklon B through the opening. The lid was made of very heavy cement. The German would never have bothered to lift it up himself, as it needed two of us.

Sometimes, it was me, sometimes others. I’ve never said this before, since it’s painful to admit that we had to lift the lid and put it back, once the gas had been introduced. But that’s how it was.

Once the gas had been thrown in, it lasted about ten to twelve minutes, then finally you couldn’t hear anything, not a living soul. A German came to check that everyone was really dead by looking through a peephole placed in the thick door – it had iron bars on the inside to prevent the victims from trying to smash the glass.

When he was sure that everyone was well and truly dead, he opened the door and came out right away, after starting the ventilation system. For twenty minutes you could hear a loud throbbing noise, like a machine breathing in air. Then, finally, we could go in and start to bring the corpses out of the gas chambers.

A terrible acrid smell filled the room, we couldn’t distinguish between what came from the specific smell of the gas and what came from the smell of the people and the human excrement.

When the job of cutting the hair and pulling out the gold teeth had been completed, two people came to take the bodies and to load them onto the hoist that sent them up to the ground floor of the building, and the Crematorium ovens.

All the rest, the undressing room and the gas chamber, was underground. Depending on whether the people were big, small, fat or thin, it was possible to load between seven and ten people onto the hoist.

On the floor above, two people collected the bodies and sent the lift back down, the hoist didn’t have any door, a wall blocked the one side, but when they reached floor level, the corpses were unloaded on the other side. The bodies were then dragged and laid out in front of the ovens, two by two.

In front of every muffle, three men were waiting to place the bodies in the oven. The bodies were laid out head to foot on a kind of stretcher. Two men, either side of the stretcher, lifted it with the help of a long piece of wood slipped underneath it. The third man, facing the ovens, held the handles that were used to push the stretcher into the furnace. They had to slip the bodies in and pull the stretcher out quickly, before the iron grew too hot.

The men in the Sonderkommando had got into the habit of pouring water onto the stretcher before disposing of the bodies, otherwise these remained stuck to the red-hot iron. In cases such as that, the work became very difficult, since the bodies had to be pulled out with a fork and pieces of skin remained attached.

When this happened, the whole process was slowed down and the Germans could accuse us of sabotage. So we had to move quickly and skilfully.

Sources:

Inside the Gas Chambers – Eight Months in the Sonderkommando of Auschwitz, by Shlomo Venezia, published by Polity Press 2009 We Wept Without Tears: Testimonies of the Jewish Sonderkommando from Auschwitz by Gideon Greif, Yale University PressSonderkommando Auschwitz. La verità sulle camere a gas. Una testimonianza unica, Shlomo Venezia, Rizzoli, 2007 The Auschwitz Chronicle by Danuta Czech published by Henry Holt and Company New York 1990 Holocaust Historical Society National Archives, Kew USHMM

Copyright Chris Webb and Carmelo Lisciotto H.E.A.R.T 2010

|