Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| |||||||

The Family Brichta Part Five – Friedland Camp and Freedom

Location, location

When I first started to look at an atlas to find out where I had been for seven months I knew that it had been close to the border of the Protektorat and that the locals spoke German. That could have been somewhere in the Sudeten which surrounds Bohemia and which was incorporated into the Reich amid rejoicing by its German inhabitants and the fleeing of its Jewish ones.

I found a Friedland which fitted that description very well. It was now called Frýdlant by the Czechs,was now within the borders of the Czech republic, it was close to the border with Germany but the present Czech administration knew nothing about a slave labour camp in their town.

That too was possible. The Sudeten Germans who had inhabited the town at the time had been driven out and into Germany for their treacherous behaviour and the newcomers from the Czech lands would not have known anything about war-time activities.

It was a researcher in Israel, himself a former slave labourer who had retraced his death march from Schwarzheide to Theresienstadt, one Jacov Tsur of Kibbutz Naan, who pointed out that there had been another Friedland.

Also close to the Czech border, whose inhabitants too had spoken German, also along the Northern border with what had been Germany and some 60 miles from my Friedland and that the Friedland I really wanted to find on the map was now called Mieroscow, had been in German Silesia but was now in Poland.

On my own I could have never guessed that, having plumbed for the easy but wrong solution. So it is possible that the train driver and those arranging his passage along junctions, signals and other trains on the line and being faced with two Friedlands close together had sent him to the wrong one first.

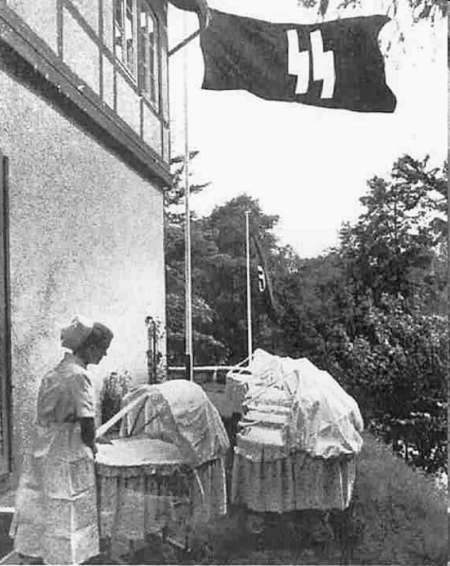

Our Lagerkommandant

When we arrived at the camp, which after Auschwitz looked quite small, we were made to stand on the Appellplatz, the barrack square, for a long time. The German Lagerkommandant, an elderly SS-man, a non-commissioned officer who was most likely a professional soldier now too old to serve at the front and sent to the rear to be in charge of a bunch of Jews wanted to pick those in charge of huts or blocks, the kapos and various other functionaries with whom he could get on with.

He wanted former officers. 300 prisoners had already arrived five weeks earlier and the man put in charge and responsible to him for this first batch was a youngish Polish Jew from the ghetto of Lodž.

Talking later to fellow prisoners who had arrived five weeks earlier it transpired that to start with there had been another Kommandant, an unpleasant character with sadistic tendencies who had been, fortunately for all of us, been replaced by the present one.

At the time I found standing tiring, after all we had been standing all night in the cattle truck, and it took ages before we got sent to our barracks for a rest because it proved difficult to find officers amongst us and it is quite possible that those who stepped forward and claimed to have been officers were mere opportunists.

To have been an officer in the German or Austrian armies during the Great War of 1914-1918 meant one was too old to have survived Auschwitz. If you were commissioned in 1915 at the age of 24 then you were born in 1891 and in 1944 you were 53 or thereabouts, Mengele was unlikely to have picked you for work and even if he had done so then the manager of VDM was likely to have looked for a younger man.

These statistics may be rough and cruel but they represented the state of affairs. That left the inter-war era. I am positive that the Polish army did not have Jewish officers even though it had many Jewish soldiers in their 1939 army and all were killed by the Germans.

I know from the conversation with an elderly Jewish locum at the Victoria Hospital in Blackpool when we lived in St. Anne's-on-Sea and that was our hospital, that he had studied general medicine and then had specialised in neurology in pre-war Poland, that all he could be in the Polish army of 1939 was a medical orderly, no good Catholic wanted to be treated by a Jewish surgeon however desperate the situation. The same would have applied to officers.

Our contingent of 165 slave labourers consisted mainly of Czech Jews with a sprinkling of German and Austrian ones and a few from Holland who had been German refugees there before being shipped to Theresienstadt and these were too young.

The Czech army did have Jewish officers and it probably had Jewish reserve officers. In the end it was a youngish Slovak who stepped forward. There were 18 Slovaks who had been added to our transport to make up numbers. The day was saved. The Pole remained top dog, the Slovak became his deputy, the decorated Austrian a block elder. Among the Czechs was Karel Ančerl. Ančerl was certainly not a metal worker.

I had heard about him, I had seen him play the viola in Schubert’s quintet in a corner of a loft of a barracks, I am not sure whether he was a conductor of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra in Prague, he certainly became one after the war before he became a conductor in Montreal where he died. I have four of his post-war records, the usual stock-in-trade of the Czech Philharmonic, Smetana’s “from Bohemia’s Woods” and “my country” (má vlast), Shostakovich’s Symphony No.5, Bruch and Mendelsohn with Josef Suk as violin soloist. I now know that he had been a conductor in the ghetto.

He was made a kapo in charge of young people and I was classified as one of these. The only advantage of that I can remember was that when a farmer brought in a dead horse, it too looked emaciated, the cook skinned it, cooked it and we had some of it. It is just possible that Ančerl had been a reserve officer.

A Czech cook stepped forward and, sensing an opportunity, claimed to have been an army cook and was duly appointed to preside over the kitchen which, as there was very little to cook with, mainly beetroot, it wasn’t exactly an onerous task. What was depressing about that was that as we grew thinner he grew fatter.

Reiser’s Perception

I will now wind forward a bit to the days shortly before the end of the war or five months from where I just left off, I shall fill in that space later. By that time very little food was about, not that there had been much before that. I know nothing about the background, I am merely quoting from p.76 of Reiser’s biography.

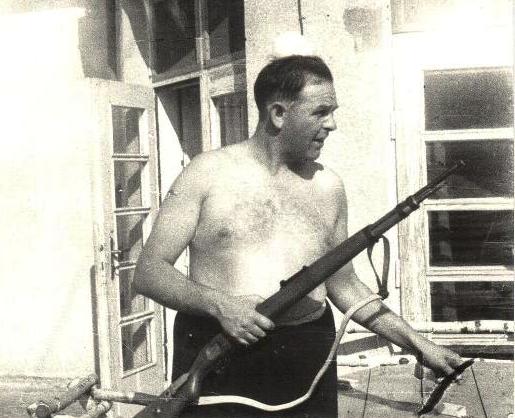

We arrive, the Kommandant is, say, a sergeant, Reiser calls him Oberscharführer but I never knew what the various grades in the SS were. Reiser insists that his name was König, so it is Sergeant König as far as I am concerned.

There are other small camps in the area. Reiser says that there are eleven satellite camps of Gross-Rosen in the area. A book on concentration camps “Die nationalsozialistischen Lager” by Gudrun Schwarz gives the names and some details of 118 of such Gross-Rosen outside camps or Aussenkommandos, see introduction to this chapter.

A Hauptmann Bauer is in charge of these eleven local camps. Both Bauer and König run the show like the battalion of a regiment. They have developed a certain loyalty to their “men” which they consider us to be. They expect army discipline under very non-army conditions. Reiser has a much better overview than I have. He works eventually, having found straightening propellers beyond him, at the Schubert sawmill and he has good contacts with French prisoners of war who can move freely in the town.

He has also moved in with the Polish crowd who are much more adapt at “organising”, i.e. pinching food although, in the end, he deteriorates faster than I do and suffers from swollen feet, water has entered the tissues during the day which is discharged during the night.

That means many trips to the latrine or, preferably because it is nearer and within the block even if the use for such purposes is prohibited, the washroom.

My Perception of the Lagerkommandant.

I never knowingly saw or met Bauer. My perception of König is this:

He was a professional soldier. Germany had a standing army, very small, the size was determined by the Versailles Conference. Germany also had unemployment (as had everybody else). The army offered some sort of security although the defeat of 1918 hung over it. When the Nazis assumed power, renounced Versailles and introduced conscription and rapid rearmament the army’s numbers had risen to at least 3 million by August 1939. By that time König was too old for active service.

The SS needed army men to supervise, guard, organise, etc. the tens of thousands of large and small concentration and slave labour camps which supplied cheap labour to mines, munitions works, aircraft factories, aircraft component factories, rocket factories (Dora Mittelbau), rifle assemblies, clearing debris from bombed fuel plants (Ruhleben), cities (Hamburg) and in the Friedland area to a propeller factory, a sawmill (Sägewerk), construction of an underground factory for the production of rocket heads, a quarry (Steinbruch) and a mine (Stollenbau), (see International Tracing Service: “Verzeichnis der Haftstätten unter dem Reichs-führer-SS, 1933-1945, p.129).

Thus the likes of König continued in employment and half of the guards serving under him were Ukrainians who spoke no German at all whereas at least two thirds of the slave labourers spoke Yiddish, which is very much akin to German, and one third spoke some or perfect German. Communication with us presented no problem. König had never had to deal with civilians in his life. His life had been the army and obeying orders was second nature. Jewish civilians were even more difficult to fit into his mental state.

He felt much more, or only, at home among soldiers and officers. So he denied the reality of the situation and in his mind we were ex-soldiers turned prisoners of war and he dealt with us through officers also turned prisoners of war.

Towards the end of the war, I can’t give a date but we were still working for VDM, i.e. VDM was still functioning, receiving castings and delivering finished sets of propellers to aircraft assembly plants, say around March 1945, two sets of 3 prisoners escaped through the lavatory window of the factory.

Prisoners had been counted out at the camp before being marched to VDM. We were counted in on return to the camp. Along the march to the factory there were guards at the front, middle and rear, to escape along the march to or from work was not possible.

However there was no counting on arrival at the factory which would have taken too long, VDM was a commercial concern. Neither were we counted out on leaving the factory. As we worked an unconscionably long 12-hour shift that gave the escapees a head start of at least eleven hours. They didn’t go far, they didn’t try to reach and join the Russians.

They knocked on the door of the first farmhouse and were hidden then and there. With the Russians approaching along the whole of the Eastern Front and the Germans being in full retreat with civilians and their belongings clogging the road a few hidden Jewish/Czech/Polish prisoners would surely gain brownie points with the Asiatic Hordes which everybody was so afraid of (because they had been so badly treated when the boot had been on the other foot).

When the Russians finally entered Friedland the day after the signing of the German surrender the escapees were back in town. What matters is that at the time there were no reprisals. After the first escape the window through which they had climbed hadn’t even been made secure, hence the second escape using the same route. There were no reprisals after the second escape.

Although the guards had an Alsatian, who was better fed than we were, no attempt was made to look for them. Amon Goeth, the sadistic Kommandant of Plaszow personally shot prisoners in the back of the head after a single escape. There may be other explanations for the inaction by König and Bauer, his superior.

It was recognised by both that it was the duty of a prisoner of war to escape and to make it back to his own line. British, and later American, Air Force pilots and crew who had bailed out over enemy territory and were captured tried to escape. If they were recaptured they would simply be put into a more secure camp, sentenced to a few days in the cooler and that was that.

For the RAF escaping was a game with fake documents, uniforms, money, rubber stamps, maps and compasses. It was accepted. German POWs did the same. Only once, after the “Great Escape” at Sagan POW Camp and Hitler’s orders for 50 of the recaptured to be shot, did it become dangerous.

I therefore believe that König took no action because he considered us to be prisoners of war, however fanciful that was, and treated us accordingly. Reiser takes a similar view. Fred Klein goes further. We were not put on a death march and our survival rate was therefore relatively large (I can decipher 15 deaths from the list of 165 prisoners or 9.09% during our 6½ months stay).

It would have been immeasurably larger had we been put on such a march. He attributes that to König’s refusal to obey an order to put us on such a death march. He says that he has some sort of proof but he has never provided one.

In fact he has and continues to behave in a most peculiar manner. I made contact with him after I had seen a review of his book in one of the newsletters of Bëit Theresienstadt in Israel which commemorates those who passed through or remained in that ghetto. I met him in London when he was on his way to the Museum Gross-Rosen. I asked him to help me to find details there of a fellow prisoner with whom I had shared a bunk and I have never heard from Fred Klein since.

Telephone calls were answered evasively. Letters received no reply even when they only dealt with pages missing from his book. Worst of all, he has made broadcasts on German TV to the effect that his experience with the German army was very positive and that has been got hold of by Holocaust deniers.

My belief is that, as a professional German soldier, he and his guards would have taken us on a death march had he received orders to do so because obeying orders was instinctive. It would also have been to his advantage. By the time the war ended he would have been in the American or British Zone and, like countless others, would have disappeared from view.

It makes sense to me that the order never came because Friedland was not in the line of the Russian advance towards Berlin. We were in a backwater. We could hear guns and planes in the distance and then all went quiet again.

Those unfortunates whose camps had been in the way of that Russian advance were evacuated ahead of it, passed our gate, stayed overnight and left their dead behind for us to bury. To leave it so late, to leave only on the day before the Russians actually arrived, was reckless.

In fact Reiser writes that, passing the local stone quarry on the first day of freedom he and his companions found some people in black clothes lying on the ground. He assumes that they were the Ukrainian SS-men who had been executed by the Russians and not yet buried.

My reason for discussing the personality of our camp Kommandant and whether or not he received or did not receive orders to evacuate the camp is that it was rather important to us.

A thoroughly unpleasant character could have made life thoroughly unpleasant for us. As it was it was a place where we would not have lasted much longer. I had the beginning of TB in one lung and Arnošt Reiser and Paul Briess, the fellow whose bunk was above mine, had swollen feet and legs from weakness, as had many others and they were excused work.

The behaviour of Oberscharführer König can be described as correct, he did not use his authority to make our lives any more miserable than they were already, but he was part of the system which had turned us into slave labourers who were lousy and starving and, had the war not have come to an end when it did, would not have survived for very long beyond that date.

One of his more unpleasant traits was to keep us waiting on the Appellplatz on Sundays to be counted. He took his time over his lunch during a very cold winter, and winters there mean frost several feet deep, and I, and I suppose others, got frostbite in both heels and my thumbs as we had neither socks nor gloves. As I rub ointment into my dry and dead heels every morning I am reminded of him.

Starting Work at VDM

The economics of slave labour

I now return to the days from 20 October 1944 onwards. We had been standing on arrival on the Appellplatz and the matter of the deputy camp elders, block leaders and assistants had been sorted out.

Very nearly all of the rest were sent to work at VDM. The factory is somewhere at the end of town. I don’t observe the land and townscape we pass through but keep my eyes glued to the ground and the feet in front of me to stop myself from slipping and sliding on the ice with my wooden clogs. To keep myself from falling takes energy of which I haven’t got any to spare. Reiser says that he worked out of doors before VDM was ready for him -that was not the case with me.

In fact the factory was keen to have us because there was an overlap of two weeks during which Czech and French workers were to show us what to do. It became obvious and is worth pointing out now that we had not been brought to Friedland to increase production, we had been brought here because we were much cheaper and even in an evil an empire as the Third Reich on the point of collapse, its armies retreating on all fronts, its Air Force in terminal decline, its factories and cities being bombed day and night, short of food and fuel even for its own German population, economic considerations still ruled.

We were simply cheaper. We were paid no wages and no national insurance contributions were paid on our behalf. The rent the manager paid to the SS for our labour amounted to a few pence. Production of propeller blades must have declined sharply. None of us were good at it, we were slow, our only incentive was to conserve, not expend, calories and it was a skilled job.

The hydraulic presses we had to use were primitive foot operated ones. I was detailed to shadow a young Czech man. The foreman was a German. There were no guards on the shop floor. One could talk. Just as the manager had been inside Auschwitz and saw its workings and probably swore blind after the war that he didn’t know what was going on, so the young Czech saw us.

As he was going to return to Prague I asked him to deliver a message to my Aryan relative by marriage, Alicia Brichtová, whose husband Oswald had been my father’s brother, and he did so.

The Making of Aluminium Aircraft Propeller Blades

The first consignment of slave labourers from Auschwitz had consisted of 300 prisoners and they were already engaged on the preparatory work on the blade by the time we arrived.

This was a production line method, a team would carry out only one type of operation throughout the shift and any shift. One team would cut off the edge of the casting, another one would cut a square thread at the root end of the propeller and another would trim the still rough casting to shape using profiles.

The cutting off of the edge was done with a continuous band saw like that used in timber yards. Every time a blade snapped it would be welded together again, when it became blunt and beyond repair it was discarded and prisoners made use of them.

Somebody made me a short knife with a wooden handle from such a blade and even managed to drill two holes through the steel so that the two halves of the handle could be connected by rivets passing through the holes.

It was a very good piece of workmanship. One day, when we were called on parade and were being searched for just such weapons, I put it under my hat and as the essential manifestation of deference was to pull one's hat off on the approach of a German I grabbed the knife at the same time and held both in my right hand.

Somebody also made me a comb from flat aluminium by cutting narrowly spaced grooves into it. We had no hair on arrival and it grew only very slowly, the body uses any available energy for more useful items, but however short it gave the lice a foothold and combing helped.

After the edges of the casting had been cut off the shape was trimmed using hand-held fast rotating milling cutters, these were steel cylinders with diagonal cutting edges in a metal housing with two handles, like machine-powered files.

These trimmers were suspended from the ceiling by long springs which took their weight and gave some control. I am not sure whether these milling cutters were powered by compressed air or electric motors, in any case it was a noisy and dirty operation.

In fact anything to do with aluminium was dirty because it is a soft metal which smears and we had no work clothing to change into. There were others who gave it a smoother finish with special files, special in the sense that they had different, coarser and more widely spaced cutting edges than files used to file steel which would have immediately become clogged up with the soft aluminium.

Our job, that is mine, Reiser’s and Klein’s, etc. was to give it the final shape and that meant carrying the blades to and from a bench to a hydraulic press, the hydraulic press being foot-operated.

My Job

The propeller blade was put on a bench on hardwood supports and a steel straight edge was placed along its longitudinal axis on the flat side of the blade. The reverse side was curved. There were three possibilities. The blade was straight, there was no gap between the straight edge and the blade. That was unlikely. Or there were one or two high points on which the straight edge rested and light could be seen below the straight edge between these high points.

The object was to get rid of the high point or points by carrying the blade to the press, putting hardwood blocks on either side of the high point, putting a piece of hardwood on the high point, make sure that this piece of hardwood was centrally below the ram of the press, lower the ram until it touched the hardwood, lock a valve and activate the hydraulic ram on its downward path by moving a lever at foot level up and down.

The foot action was translated into a small but very powerful downward movement of the ram. How much to move one’s right foot up and down, i.e. how much to move the ram to create a permanent set in the aluminium was a matter of skill and judgement. Aluminium is a metal and obeys Hooke’s Law. Too little pressure and the blade will spring back to its original position and nothing will have been achieved.

Too much pressure, i.e. too much travel of the hydraulic piston and the blade will bend about the two hardwood supports and will result in a permanent set, i.e. beyond the elastic limit, of a size greater than intended, the blade will now exhibit a bend or high point too much the other way as discovered when taken back to the bench and tested with the steel straight edge.

That means taking it back to the press, lining up the hump under the ram and repeating the process. The same thing can and often happens again. Too little pressure and nothing happens, it is a wasted effort. Too much pressure, or travel of the ram, and the result is a permanent set the wrong way. The foot-operated pump gives you no “feel” of the pressure although there is a gauge. It is a matter of experience although there ought to be a relationship between the size of the hump to be removed and the pressure needed to achieve that.

On the other hand the cross-section of the blade and therefore the stress induced by a given deflection varies across the length and what may be the right pressure near the more solid threaded end that fits into the propeller boss of the engine is far too much for its thin section at the far end.

Pressing that foot pedal which lowers the ram just a little bit each time is tiring. The shifts lasted for 12 hours, we didn’t. Nobody, with the best will in the world, could have worked that press, carried a heavy blade made out of a light alloy but of solid cross-section forwards and back and lift it into position and bend one’s back to check the result for that many hours and we were obviously more interested in preserving our strength than producing propeller blades to the right degree of straightness.

Klein says that there was a minimum number to be made per prisoner per shift and, if there was, none of us achieved it. All we were looking forward to was the break halfway through the shift when a trolley loaded with an insulated contained with soup arrived.

After that the rest of the shift dragged on interminably. Ergonomically the system was inefficient. The Germans generally didn’t seem to have been concerned with efficient working practices, from marching long distances between camp and work place so that labourers arrived tired to relying on brute force rather than lifting gear.

After the raid on Peenemünde on the Baltic coast which was all but obliterated by the RAF in August 1943 the production of the V1 and of the V2 rockets was shifted to a factory known as Dora Mittelbau at Nordhausen deep in the Harz mountains.

There 60,000 slave labourers worked under appalling conditions in what had been calcium sulphate mines and still oozed sulphurous stench. In the 20 months between the move to Nordhausen and the end of the war in Europe more than 20,000 perished in the tunnels and galleries.

Tuberculosis, pneumonia and dysentery were rife. Tools to extend the underground works were always in short supply. Prisoners were ordered to scrabble with their bare hands to clear rocks and rubble and to manhandle heavy machinery into position. Those who faltered were brutally beaten by the guards. Those who died were neatly stacked so as not to interfere with work, and then removed with forklift truck at the end of the shift.

Work in any of the tunnels was calculated to shorten life but the most grisly of them all was Gallerie 39 to which a posting meant a sentence of death. Gallery 39 was the galvanising shop whose toxic chemical fumes ate way the lungs of anyone who worked there.

No one survived for more than a month. This was a self-defeating regime because using such methods only 20% of the V2s demanded by Hitler were actually produced.

Even that was enough to kill nearly 3,000 people in London and wound 10,000 more. Arthur Rudolph, the civilian director of “Dora, the Hell of All Concentration Camps” by Jean Michel, an ex-inmate of Nordhausen, published in 1975, was spirited away to the USA where he was showered with honours when his effort, and that of von Braun, culminated with Neil Armstrong stepping onto the moon at 2:56pm on 21 July 1969. (From The Times’ obituary of Arthur Rudolph of January 4, 1996)

My Foreman

There was no guard on the shop floor. Our foreman was a small German civilian who was clearly irritated by our lack of skill and low output but he never lost his temper. He had an agenda of his own and that was to use his good behaviour towards us as a bargaining chip should the Russians arrive and they were on their way as he well knew.

He told me that the factory had come from Hamburg and then he confided that he had been a member of the Communist party. Pre-Hitler the Communist party in Germany had been a mass membership party and the port of Hamburg would have been just the place where they would have been active, but that is not the point.

The point is that the war was not yet over, it still had four months to run when he confessed, the Nazis were still very much in control, so why mention it to a 16 year old Jewish boy? Surely only, should the situation change, I would put in a good word for him. Occasionally he would also give me a very hard crust of bread. It had been intended for his rabbit but he felt that I needed it more. Quite true of course and it tasted delicious, cake could not have tasted better.

Christmas 1944

One night, we were sitting down on the factory floor having our soup, when somebody said: “It must be Xmas!” Presumably a foreman had mentioned it. We were Jews, although there were a few Catholic converts amongst us, and it didn’t mean all that much except as a date, a milestone.

By that time the Western Allies were on the Dutch border and the Russians were on Polish soil. We didn’t know that but the German population of Friedland did.

An Addition to our Numbers

We had a surprise addition to our numbers. One day a German soldier, or shall we say a former German soldier, arrived under escort from the Eastern Front. The explanation for his arrival was quite simple, a Jewish grandmother or grandfather was discovered among his ancestors, something that many Germans tried to hide.

With such an impurity of Aryan blood running in his veins he was not allowed to die a Heldentot (hero’s death) and he probably committed a misdemeanour when swearing allegiance to the Führer and all his works. Of course, they could have sent him home because even by then only those with one Jewish parent were sent to Auschwitz and, if they survived there, were sent to a slave labour camp, as were Paul and Alois Kling with whom I shared a room in the ghetto.

Such 50% Jews were definitely made to know their station in the German racial hierarchy, they had to wear a star and would have never been admitted to the exalted membership of the German army even if, for some perverse reason, they had wanted to.

Where only one out of four grandparents was Jewish, i.e. one-sixths Jews fared naturally better. My schoolmates from the Jewish Reformgemeinde Schule in the Joachimstaler Str. In Berlin, the brothers Fritz and Hans Behrendt, whose family had fled to Holland because their father had been an active anti-Nazi and the Gestapo were after him, had just one Jewish grandmother and, although called up and in German Air Force uniform, were kept in the reserve and were not sent on active service.

As Fritz says, their Jewish grandmother saved their lives. In the Friedland case the change must have come as a shock to the system, one day a proud soldier, even of an army now in retreat, next day a miserable prisoner in a labour camp with, literally, lousy Jews.

It would be wrong to say that nobody talked to him. We didn’t because for all we knew he may have committed atrocities against Jews and certainly had been a Nazi, but somebody must have found him trustworthy because he was one of the first three prisoners who escaped and all three had to hatch that plan together.

The Death of my Dutch Friend Levi

The weeks dragged on. Interrupted sleep due to nothing but liquid food, a difficult march to and from the works on an icy road with smooth, wooden clogs, exhausting long hours of work. The body growing weaker offering no resistance to infection, people died of the consequences of starvation. I had made friends with Hans Karl Levi who had been a German refugee in Holland, had been sent from there to the ghetto of Theresienstadt.

The many years of homelessness had left him weak to begin with. One night I found him in the sickbay, a room with something like three beds, a prisoner acting as a nurse and a doctor, there was no shortage of doctors. He died a day or two later. The sickbay had no drugs and it wasn’t drugs but food we needed. I was told that he went mad just before he died, that urine had entered his bloodstream.

I am no doctor and I can only suppose that his general weakness had caused kidney failure. The list of inmates notes that he died on 3 March 1945.

Own Deterioration

I too called in at the sickbay. I had the habit of pulling my cuticles, the skin on the base of my finger nails. Nowadays it would have had no consequence, then such small wounds became septic, puss would form and I would lose the nail. The sickbay had no antiseptic ointment, all they could offer was elastic paper plaster. Neither would a nail grow again as it does now.

The body was pre-programmed not to spend reserves on anything as unnecessary for the preservation of life as growing hair and nails. Although, e.g. I had started to shave, with my father’s cut throats which I still have, at the age of 13 on the outset of puberty, I needed no shave throughout the seven months at Friedland.

I lost the nails of every finger and when they eventually re-grew they did so, and still do, not smoothly but unevenly with pronounced lines.

Reciting Schiller

When I lived in Prague I read a lot. School was very undemanding and half-day and I had nowhere else to go, all places of entertainment, sport, public transport, parks, anything beyond the city boundaries was barred to Jews, my mental energy had to have an outlet. There were my popular science books but also Schiller, Goethe and Lessing, the popular German poets and dramatists. That was long before, by some seven years, before

I understood any English and although I also spoke Czech there were no Czech equivalents or none that I came across. I did read “The good soldier Švejk” in the original but didn’t really appreciate it fully because that needed a background of Austrian-Hungarian Empire society.

Of Schiller I read “Wilhelm Tell”, of Goethe “Faust” and of Lessing “Nathan der Weise”. For a twelve-year old it is not easy to just read a play but that is all I had. Why I read Wilhelm Tell is self-evident, it was the fight of the oppressed against the oppressor, a mirror image of our times with which I empathised.

Now I know that the oppressed Swiss turned into a rather unsavoury bunch fully collaborating with the Nazis but I was unaware of that at the time. Sometimes in the evening while at Friedland I would leave the hut and recite the relevant passages so as to reassure myself that, in the end, good triumphs over evil.

Although by now, sixty years later, I have forgotten my German through lack of use, opportunity to use it and deliberate effort not to use it, I can still recite: “…mach deine Rechnung mit dem Himmel, Vogt, fort musst du, deine Zeit ist abgelaufen”, do your reckonning with heaven, Vogt (the Austrian governor), you must go, your time has come,” equating the Vogt with Hitler. Preceding this there is also: “…durch diese hohle Gasse muss er kommen…”, through this narow passage he must pass,” that’s where Tell waylays him after he had made him shoot the apple off his son’s head.

I also recited other poetry, some which I had learned at primary school in Berlin and which I also still remember are, from “Die Kraniche des Ibycus” to “Zu Dionys dem Tyrannen kam Mänos, den Dolch im Gewande, ihn schlugen die Häscher in Bande. “Was wolltest Du mit dem Dolche, sprich”, entgegnet ihm finster der Wüterich, “die Stadt vom Tyrannen zu freien”, “dass sollst Du am Kreuze bereuen”.

It too is about an idealist Manos who wants to free a city from the rule of the tyrant Dionysius. He approaches him with a dagger hidden in his garments, is caught by the guards, brought before the tyrant who asks him what he intended to do with the dagger. To free the city from the tyrant to which the latter replies that Manos will regret that upon the cross. It goes on for several pages. All in hexameters.

With Faust I only identified in the last passage where he declares: “Wer’d ich zum Augenblicke sagen: “verbleibe doch Du bist so schön, dann kannst Du mich in Fesseln schlagen, dann will ich gern zugrunde gehn.” Should I ever say to the moment: “stay a while, you are so beautiful, then you can cast me in fetters, then I will gladly perish”.

By that he meant, I think, that the price he had to pay the devil was not only his soul but also restlessness, always busy, never taking a break. At least I have that in common with Dr.Faust.

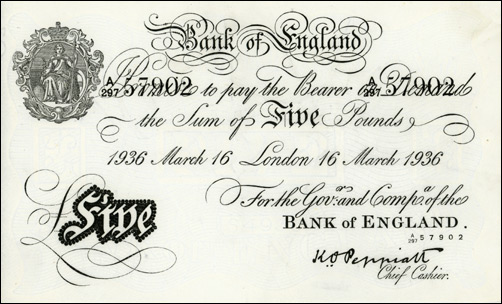

Call for Engravers and Printers

One day a call went out for printer-engravers. Since all of us had claimed to be metal workers of one sort or another there was no way the camp administration could know who had such a trade. There was one fellow prisoner who actually fitted that description and he hummed and harred and couldn’t make up his mind whether to own up. He would be taken somewhere else and that could be better or worse.

The old army adage never to volunteer for anything should have warned him. May be he felt that conditions would be better, none of us knew that they were mostly worse.

May be he wanted to do what he had always done. In short he volunteered and was taken away. I now know that the Germans tried to wage an economic war as well and wanted to flood the international market with forged Pound Stirling notes.

Apparently, with all facilities at their disposal, the forgeries were indistinguishable from the real thing though the distribution of the forged money never happened. Stories abound, one is that all Jewish engravers and printers were murdered once they had completed their task.

Death Marchers at our Gate

The winter of 1944/45 was a particularly harsh one in an area which has always had cold winters where the temperature never rose above freezing. In Prague the snow that had fallen in October was still there in March and we were even more easterly.

Death marchers were on their way West to prevent them being liberated by the Red Army and concentration and slave labour camps in the path of the Red Army on her way to Berlin were being evacuated, as were, by the way, prisoner of war camps.

An estimated 100,000 Jews died during these death marches, either they died of weakness or were shot when they were too weak to carry on. Even Gross-Rosen, our administrative centre and a large concentration camp with 51,204 male and 25,728 female prisoners on 1 January 1945 was evacuated, some to Theresienstadt on foot, some to Ebensee by rail, mostly in open carriages.

The Red Army entered Gross-Rosen on 13 February 1945. The bodies of the murdered Jews from all over the East were thrown into the nearest roadside ditch. Our experience, while no less gruesome, is slightly different.

It was probably February 1945 when columns of death marchers passed our gate. Our camp had a single-track railway line along one side of the barbed wire enclosure and a road along another side at right angles to it. German refugees with farm carts were passing through though I didn’t see many, it depended which shift you worked and whether you were awake and about at the time.

Rumour had it that they threw hard-boiled eggs over the wire but I certainly never had any, however long lines of Jewish prisoners passed too.

Again, I cannot say that all of them stayed overnight with us but many did. With half of our camp being absent from their bunks when on night shift a temporary bunk could be found and, if nothing else, it gave them a rest and I dare say the guards welcomed it too. I remember one such contingent in particular, they were Italian Jews and, it being a sunny day before they set off again sang to us.

What was different about those long columns of slow marchers was that they were ordered to carry their dead along, heaped onto a farm cart with a long shaft in front. Normally pulled by horses, and with sloping open sides, ideal for carrying hay but this time piled high with corpses.

Not only must it have been an enormous effort just to keep moving on icy roads because ours was a hilly area. To have to pull or push a heavy cart can only have added to the effort and the nature of the load , constantly reminding you of your impending fate when it became too much, didn’t help.

Why some were left where they died or had been shot and others were being carted around I don’t know. With millions on the move such inconsistencies would occur, my part of their story is that they left their dead with us to bury and I was on several burying parties.

Burial Party

We too had a cart. The corpses were very nearly naked, they didn’t need their clothing any more, they were completely emaciated, skeletons covered with skin. . The odd thing about them was that they had grain all over their bodies, whole kernels of wheat.

The question for the local German authority was where to have mass graves dug. Naturally we were not privy to their deliberations. We were simply told to push the cart piled high until we came to the wall surrounding the local church.

Again, I don’t know what its denomination was. We were told to dig a short distance from that wall. A mass grave can be dug at the nearest convenient spot. It seems that the farmers nearest to the camp didn’t want it in any of their fields.

They did not know that, just like Germany after its unprovoked invasion of Poland had driven Poles from their properties and had handed these to Germans to consolidate their Drang nach Osten (drive eastwards for more Lebensraum/living space and the devil take the existing local and rightful population), it would soon be their turn to be told to go and make room for Poles, just as Poles had to move westwards to make room for Russians in Russia’s westward drive.

The church presumably didn’t want a mass grave full of infidels within their hallowed walls and in consecrated ground. The compromise was to have the mass grave just outside the churchyard. That is where it is and I wished that at least a plaque would remind those passing by that there lie hundreds of Germany’s victims who died the most terrible of all deaths, hunger.

Digging a deep pit in winter in (what is now) Poland is easier said than done. The ground is frozen solid for at least three feet (a metre) may be more. Depending on the moisture of the soil it is like ice or solid rock. We had a pick but even lifting a pick is hard work when you are weak. There were always one or two exceptions. There was a small but powerfully built man from Lodž who made short shrift of it.

There were always some among the contingent from that ghetto who would find potatoes, roast them in the ashes of the stove in the block or hut, keep their strength up and do jobs we ordinary Czech Jews couldn’t do any more.

Reiser mentions the source of such food and the stove in the tailor’s workshop used for such purpose but sometimes one of the two stoves with long pipes, it was the pipe which gave off the heat, when lit.

I believe that Friedland had a coal mine and the timber yard could have supplied waste wood. Once through the thickness of the ice the rest wasn’t so difficult. The bottom of the pit was levelled, or was dug to a level surface, the corpses, very light, very stiff due to rigor mortis and the frost, were slid down into the pit where they were laid close together and sardine-like to occupy the minimum of space.

When all had thus been deposited slaked lime (quicklime) was spread over the top layer to dissolve flesh and bones and the pit was backfilled. I wouldn’t have known how to say a kaddish and whether anybody did so quietly I don’t know either. Then we trudged back to camp pushing the empty cart. I went on several but not on all such burial parties.

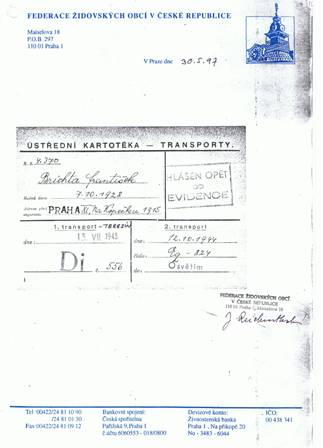

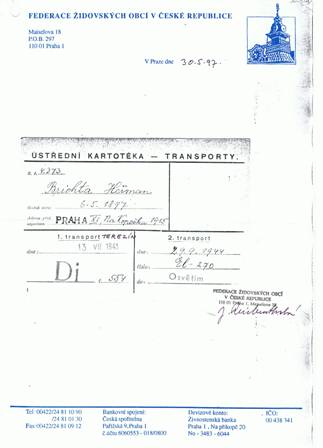

The List of the Thersienstadt Prisoners

I remember the long list being compiled in Friedland long after our arrival there. For some year I have known the exact date when it happened. I handed my claim against Germany to a firm of Jewish lawyers who had formed URO, the United Restitution Organisation, with offices in London, Berlin, New-York, etc.

I filled in a form stating all the facts and dates I knew and URO carried on from there but did not keep me informed or sent me copies of the many statements and documents it unearthed and which would have been of interest and use at the time and later.

Not every Jewish organisation was exactly helpful. The only document sent to me at the time, another copy was sent to URO, came from the International Tracing Service in Arolsen, Germany, a branch of the Comité International Croix-Rouge of Geneva and was a “Certificate of Incarceration”.

It is the third carbon copy from the days before photo-copying and is somewhat smudged. It was sent on 20 February 1956. It is taken directly from the list of prisoners because it has the same wrong spelling of my name, Brychta instead of Brichta, it has 1925 as my year of birth instead of 1928, I made myself older as advised at the time, it gives my profession as “Bauschlosser” (locksmith) as on the list a copy of which is now in my possession, and it has my correct prisoner number, 73803, in KZ Gross-Rosen/Kommando Friedland which appears nowhere else.

In fact under “Records consulted” it says that it was the “Häftlingsliste”, the list of prisoners of camp Friedland. The significant date for my purposes is “6.Dezember 1944” the date the list was compiled. It was not compiled before or just after our arrival in Friedland from Auschwitz but seven weeks later, when we were given strips of cotton fabric with the number shown on the list, to be affixed to our outer garment, the jacket.

The list shows that, in spite of being officially just numbers, there had been a serious attempt to put us in alphabetical order using our real names. The same applies to the list of the first consignment of 300 prisoners, originally from the ghetto of Lodž/Litzmannstadt and sent to Friedland from Auschwitz on 6. September 1944, an equally illegible copy of which I obtained from the Auschwitz Museum.

Some Statistics derived from the List

The list has the heading: “Transportliste” and below that: “Über die am 19.10.1944 vom K.L.Auschwitz nach K.L.Gross-Rosen, A.L.Fried- land überstellten 165 jüdischen Häftlingen”

(Transport list of 165 Jewish prisoners transferred on 19.10.1944 from K.L. Auschwitz to K.L. Gross-Rosen, A.L. Friedland)

where “K.L.” = Konzentrationslager and “A.L.” = Arbeitslager or (slave) labour camp

Some statistics using the age distribution of the 165 male prisoners delivered to the German firm V.D.M. of Friedland in Lower Silesia who left Auschwitz on 19.10.1944 and arrived on 20.10.1944.:

Originally from the ghetto of Theresienstadt: 133 Originally from the ghetto of Litzmannstadt (Lodž): 11 Originally from Slovakia: 18 Originally from Hungary: 3 Total 165

Died in labour camp Friedland: 14 (8.5%)

Average age of the 134 (81.2%) of those prisoners whose date of birth can be deciphered, in Oct. 1944 when most of them had arrived in Auschwitz:

33 years and 5½ months

50% of the prisoners, 25% either side of the mean of 33½ years consisted of 34 men from the age of 23 to 34 men of the age of 40, i.e. 50% about the mean age was within the ages of 23 to 40,

Of the rest, the remaining 18% consisted of 27 men and boys aged 14 to 23 years and 31% consisted of 42 men between the age of 40 and 52.

There were thus more older than younger men.

That seems to contradict the view that Dr.Mengele picked young people for the hard work expected of a slave labourer and sent only the older ones to the gas chambers. Here we have only18% of the young but 31% of the over 40s and 50% between 23 and 40.

It also contradicts the view that the last 10 transports were sent from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz to fill Germany’s armaments factories. If each transport consisted of apprx. 50% men and 50% women then to “yield” 165 male workers promised to VDM there had to be 2x165 = 350 survivors from the 1,500 ghetto inmates sent by transport “Eq” on 12.10.44 who were intended to go to Friedland and, if the range was 14 to 52 years then 330 (or 165 men) could have been found from that one transport.

In fact only 78 men and women survived. Likewise of the next transport “Er”, which also consisted of 1,500 men and women only 117 survived so that 68 men had to be found from earlier Theresienstadt, Lodž, Slovak and Hungarian arrivals.

It would appear that killing arrivals and not make use of them, or enable others to make use of them, was the priority whatever the demands of industry and of outfits like “Organisation Todt” which used slave labour to dig underground caverns to house factories safe from accurate bombing and bombing became more accurate as the number of interfering German fighters decreased due to lack of fuel, the shortage and lack of training of pilots and the use of Mustangs (P-51s) as escorts.

Tank Trenches and Other Work

There came the day when V.D.M. had to close its doors. Due to the Allied bombing of factories, possibly of the aluminium foundry producing the propeller castings, the bombing of railways, railway junctions and trains and the shooting up of locomotives by Typhoon fighter planes now that its limited range of 510 miles was ample once the Allies had crossed the Rhine during the middle of March, castings stopped being received and finished propellers could not be dispatched.

I remember the mathematician Dr.Otto Fischer being marched to the factory by himself to finish balancing the last remaining pieces. And, although the writing was on the wall the economics of the system continued, in other words we had to work to earn our keep.

Since VDM had dispensed with our services for which they had paid, we were now on the market for a new employer and several sources were found. Fred Klein writes that he was transferred to the construction of an underground factory which was to produce war heads for the V2 rockets.

That involved carrying heavy sacks of cement and in his memoirs he describes how he dodged such heavy work by disappearing into the latrine.

There are two surprising aspects of the German economy even in its death throes. Cement is the result of burning and grinding clinker and uses a large and expensive quantity of electricity in its manufacture.

In Germany electricity was generated in coal-fired power stations using poor quality brown coal, the same coal from which aircraft and diesel fuel was made and which powered the rail network, the only means of transporting everything. It was fuel shortage which stopped the German last ditch tank offensive at Avranches and fuel shortage which denied the Germans aircraft support which was vital. And yet to the last minute there seems to have been plenty of cement.

At one time all of French coal was delivered to Germany but since D-Day French collieries ceased to contribute to Germany’s economy. The same applies to aluminium. Aluminium is made by smelting bauxite and here too enormous quantities of electricity are used in converting one into the other. Yet to the last minute aluminium in the form of sheets and ingots were available.

Working for the Luftwaffe

My first job was to work with a small group of other camp inmates for the German Air Force under Luftwaffe officers on some experimental scheme involving spot- welding together two halves of a container made of pressed sheet aluminium.

The containers in their final form were pear shaped, i.e. circular in cross-section, circular or spherical at one end, pointed at the other. It had an aerodynamic shape. I guess it was a disposable fuel tank to extend the range of an aircraft.

The two halves, each with an inch wide rim, came ready-made and the experiment consisted of finding the best way of spot-welding them together. I don’t know enough about it, none of us did, but it had to be volatile fuel proof and aluminium has a low melting point, it was easy to make a hole rather than a proper weld.

The prisoner chosen to operate the spot welding machine was a qualified electrical engineer who in his pre-German invasion days had been in charge of a power station. This job didn’t last long.

Working for the Local Defence Committee

The next job was quite different, it was to dig a deep and wide anti-tank trench. We were now probably in the employ of the local defence force. Now this trench was across a field, never mind what the farmer thought of the idea. To us it was a job we did reluctantly, it didn’t make sense. The trench was quite long but it could be bypassed, the Russian T34 could overcome most obstacles, the road was left undamaged, probably to allow German refugees through.

So, all in all, it was a waste of effort but our’s was not to reason why. Nevertheless I felt that there was no real pressure to get on with the job and complete it, the locals felt that the red tide was inexorably rolling towards them and that this, or our, effort wouldn’t change that.

In connection with marching to the field, and it was spring now, there was no icy soil to contend with, we met Polish prisoners of war in their light green greycoats down to their ankles and in spite of my own condition I felt sorry for them because they had been prisoners of the Germans who had treated them with utter contempt since September 1939 or for 5½ years.

At that time I knew nothing about the fate of Polish Jews, they had been killed outright, including those who had been soldiers in the Polish army. Of the sixty thousand Polish soldiers who were killed in action six thousand were Jews and of the fifteen thousand civilians killed in Warsaw when the Germans bombed it three thousand were Jews.

When the trench job had come to an end the local defence committee, or whoever it was who now employed and paid for us, had another wheeze. This was a wooded area, fir trees grew on either side of the road. The road was in a cut, i.e. it had upward sloping sides. We would cut down trees, the cut down trees would be rolled down the slope and be stacked to form a tank obstacle.

First cut down your trees. The first difficulty was supervision. We were now widely dispersed, two or three prisoners per tree otherwise we would get into each others way and only one could hack away at any one time using a hatchet.

There were not enough guards to go round and there were no hatchets. It was decided that the locals would guard us and supply the tools. The locals, elderly men all, the young ones were in the army or at work, were armed with shotguns and were frightened of us.

They were in three minds. We looked rather forbidding, haggard, without hair or with a short length of hair and a most conspicuous swathe cut through it from front to back down to the scalp, that’s what I sported, in very worn out clothing with large crosses painted on the back, all most unprepossessing.

I am not sure that it dawned on them that we were Jews, their preoccupation was that we were prisoners of the Reich, our appearance made it obvious that we had not been well treated, that we were enemies of the Reich and therefore, by implication, friends of the Russians who were standing at the gate.

It wouldn’t do them any good treating us harshly. But they had a job to do, a job in which they didn’t believe themselves. A salvo from a tank would splinter all the trees put in the way.

More to the point, creating an obstruction might count against them. They were not really keen to insist on us doing something that might backfire. This attitude was in direct contrast to that exhibited by German women and children within Germany who threw broken glass at the feet of death marchers when defeat and retribution were not that immediate.

Anyway, our new guards had brought axes. Strictly speaking, the best way to cut a tree down was with a “Canadian” saw, a long, wide, coarse toothed saw with two handles, one at either end, each of two tree fellers pulling in turn.

To use an axe it has to be a really big and heavy one and you have to know what you are doing otherwise much effort is wasted in chipping away. It is hard and skilled work. They had brought small hatchets from home used to split logs to put on a domestic fire.

We played dumb. The hatchets just bounced back. They showed us how to do it but only for 30 seconds or so. That reminded me of my father telling me about Russian foremen on the Trans-Siberian Railway doing exactly the same when he was a POW there 1915-1917. We explained that we really didn’t have the strength. And we didn’t. After two days at the most they gave up on us.

The Beginning of the End

This was now the end of April. Reiser would still go to the timber yard where work continued to the last minute and Klein would be marched to the underground factory site, but most of us were sitting behind the wire in the sun.

I remember a delivery of carrots from, presumably, a local farmer. These were the previous year’s stored under a mound of earth which acted as insulator protecting them from frost. It was warm, a wonderful feeling after the constant cold of the winter, which had sapped our strength, and eating raw carrots. Things were looking up.

The Disappearing Guards

The end was obviously nigh. That didn’t mean that we would see it alive. There were still the watch towers manned by Ukrainians who had always, throughout history, been ill-disposed towards Jews and they had machine guns.

It only needed a call to assemble, a few hand grenades, short bursts of machine gun fire and that would be the end of us. We were aware of that. We were so near and yet so far. Anything could happen.

Until now we had a German camp commander, an Austrian corporal and the rest were Ukraininans. In relative terms the German was best, the Austrian felt that he had to prove that he was a good German and he was pretty miserable specimen to start with.

The Ukrainians felt that they had to prove that they were at least as good, or as bad, as the Austrian and if they hadn’t been forbidden to injure us which would have interfered with VDM’s production schedule, they would have clubbed us with their rifle butts at every opportune moment.

Whatever was happening at the front, however closer it became, there was no guarantee that we would be liberated alive. We had no clock, no radio, no newspaper, no calendar, so I am not sure whether it was on the 7th or 8th of May, but it was likely to have been the 8th, the day the war actually came to an end, the German forces surrendered unconditionally on 7 May on Lüneberg Heath, not that we were aware of that.

We were indeed called to assemble on the Appellplatz and stood in our usual formation. The Lagerkommandant appeared in an outfit we had not seen him in before, with a leather belt contraption that looked like the braces worn to support Lederhosen, i.e vertical braces with a horizontal piece at chest level connecting the two.

He gave us a short address, something he had not done before either. The gist was that would we please remember that he had treated us decently. And then he was gone. In other words, should it come to pass that he too would have to answer for the crimes committed by the SS of which he was a member and in whose system he played his part, would we please put in a good word for him!

Everybody else had gone too, the large gate through which we had entered and left so often was left open. Then the rumour circulated that an Ukrainian SS general by the name of Vlasov was in the vicinity and that it would be a good idea if we left the camp and spent the night in the nearby woods as his troops were quite capable of throwing a few hand grenades over the fence. The current must have been switched off too. We left and spent the night in the woods.

Both Reiser and Klein provide a lot more detail but as usual I did not take any of it in. I was in my usual only-half-awake state. I repeat their version with the proviso that I am quoting others. “Reiser does not even mention König’s speech, Klein mentions it in passing.

Apparantly the Ukrainians on the two watch towers were carrying up ammunition boxes while we stood to attention and that certainly was not a good sign. We were also ordered to change our formation so that no man stood behind another one, the first row acting as a shield. That too was an ominous sign.

The Ukrainians’ machine guns were trained at us for something like an hour, or so it appeared to the reporters, after which signals were made by the Ukrainians in one tower to that in the other one, they had a conference, then some more signals after which they descended from their respective towers carrying their machine guns but leaving the ammunition boxes behind.

They walked past us between the two rows of barbed wire and drove off. The formation then disintegrated and we made our way individually to the woods."

The Arrival of the Red Army

This was the first week in May somewhere between Central and Eastern Europe. The night was warm, spending the night out of doors in the fresh air was pleasant. The chances of anything going wrong now were small. I had no thought in my head, I just didn’t know what to expect.

In the morning I got up and went into the town, free to do so. It was, or seemed to be deserted. I reconnoitred a bit, my aim was to find a change of clothes and something to eat. I found a large cellar full of barrels of what I took to be cider.

Shoes were my next concern, the clogs given to me in Auschwitz in exchange for my shoes had ruined my feet because they were solid, not flexible, and it was difficult to walk in them. I entered a shoe repair shop but found little except a pair of German army boots. I took them and soon found out why they had been in the shop for repair, there was a nail protruding from the heel.

I went into various houses. The doors had either been left open or somebody else had been there before me. At first I found nothing to eat, what the Germans had left behind were large glass jars of things like goose liver in solid goose fat, something I knew would be real poison.

I had not eaten fat for years and the digestive system, the bile, liver, stomach had lost the enzymes, the means to deal with it as it had for most things. I was more likely to digest grass or plants resembling beetroot, our staple diet, i.e. cellulose. Yet somehow, and I cannot remember where and how, I found a change of clothes, shoes which fitted and something to eat.

Then the Russians arrived. The victors looked somewhat dishevelled and dirty, for them too the war had only just come to an end too. I recognised their uniforms from my father’s photographs of the Czar’s soldiers, the fashion hadn’t changed, the high collar with buttons along the shoulder.

They had arrived by horse and cart, the most economic way of travelling, they had advanced so far their lines of communication had become enormous, just like those of the Germans had shrunk.

To deliver petrol for the movement of every Dick, Tom and Ivan all the way from Baku or wherever would have been logistically difficult and costly and anyway, this type of soldier knew all about horses but couldn’t necessarily drive a truck and trucks have to have spares and need to be maintained too.

Horses one could pick up from German farms, just as the Germans had done from Polish, Ukrainian and Russian farms on their march forward four years earlier. In contrast the few officers who came and went came and went by car, possibly captured German open or convertible Mercedes, had immaculate uniforms of dark blue serge and had spotless soft well fitting calf length boots of polished soft leather.

The contrast between officers and men could not have been starker, nothing like in the British and American armies when I saw these later. I was at that time left leaning and had heard about class war, in which case Russia needed a communist revolution, this was class distinction par excellence.

Of course, I was more than pleased to see them, it didn’t matter what they were wearing but I was astonished. The first Russian I met asked for “časy” and “vodka”. I knew what he meant because “čas” in Czech is time, časy must have something to do with time, i.e. watches.

With them I couldn’t help him. Watches were a desirable prize, successful soldiers had several on an arm. I knew what “vodka” meant. “Voda” in Czech is water. Vodka, or rather vodička, is the diminutive. What it really means is “firewater” although any degree of alcohol also fits that description. With that I was able to help him and I took him to the cellar which I had found earlier.

With my new, or second-hand, shoes and shirt and trousers, May 1945 was a particularly warm month, I needed nothing else, I set forth to have a look farther afield. A certain euphoria took hold of me, it was a last outburst of happiness caused by the knowledge that I was, nominally at least, free, whatever that meant, before real life in an unknown world, for which I knew I was ill prepared, cut in.

I went into the countryside singing the first verse of the Marseillaise on top of my voice. I had no French but in Berlin we had a very thick illustrated book, a small version of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, of general knowledge and I lapped it up and memorised it without trying.

Thus I will always remember that Cato the Elder used to finish every one of his speeches with “ceterem censeo Cartaginem esse delendam”, that the Romans held that “si vis pacem para bellum”. I had always known, and could confirm, that “homo homini lupus” , that “ “ signa te signa, temere me tangis et angis” could be read backwards and so I also knew that “Allons, enfants de la patrie, le jour de gloire est arrivé”, and it had, had it not and “contre nous de la tyrannie”, surely yes, how fitting, it is a rather rousing tune and if I got some odd looks from passers by who were possibly French, so what.

I have a recollection of passing along large, curving drainage ditches by the side of the road which were filled to the top with abandoned Panzerfausts, a very effective, simple, self-propelled rocket used, as the name suggests, against the caterpillar tracks of tanks, demobilising them.

During the last days of the war in the battle for Berlin the Hitlerjugend shot up hundreds of Russian tanks with them. No such enthusiasm for the bitter end occurred in Friedland.

The First Few Days of Freedom

Many of us went back to the camp. There was nowhere else we could go though, on the other hand, we could have squatted in one of the houses vacated by the Germans until we were ready to depart to nowhere in particular, since our homes had gone, burnt down in the case of Poland or occupied by Czechs in the case of the Protektorat but we didn’t.

But then staying in the camp wasn’t the thing to do either and the Russians left us to our own devices. Russian soldiers came to see us and offered us tobacco. That was a very friendly gesture. To those who wanted it they gave it away by the handful from their pockets.

They rolled their own cigarettes using newspaper, such refinement as cigarette paper they didn’t have. Newspaper burns well but it is rather thick. They therefore tore off a strip of newspaper just a bit wider than a standard cigarette length and rolled a cigarette of medium cigar thickness.

That would provide the same proportion of tobacco to paper as in a normal cigarette but at least four times the volume of tobacco. These were the third class soldiers. The first class had raced to Berlin and their losses there alone were greater than American losses in both the European and the Far East theatres of war.

That group had included tank drivers and gunners, katjusha rocket operators, gunners, signallers, ambulance drivers, those looking after supplies of every kind over an ever increasing distance. The second class were that part which mopped up cities and fortresses like Breslau and Küstrin which had only been surrounded and isolated. Our bunch now filled the empty spaces which had not been affected by the drive into Germany proper, like Friedland.

They were good with horses but I am not sure that they could have driven a truck and neither was there any need to. They drank hard, they smoked like chimneys and they had fought hard when required. But strictly, they had not liberated us.

By the time they arrived the Germans had left and the war had come to an end and, as I shall mention shortly, apart from acts by individuals, such like offering tobacco, they ignored us.

We knew absolutely nothing about the conduct of the war after we had left Prague other than rumours and few of those. We knew nothing about “uncle Joe” except that he had made a pact with the Germans in 1939 and that still stuck in our gullet because it had made German victory over Poland inevitable and had helped, materially anyway, to bring about German occupation of Europe and contributed to our perilous state, though how perilous we didn’t know yet but our passage through Auschwitz had given us some idea.

On a Local Farm

I had made friends with a young Pole from our camp and we decided to stay together for the next few days. He possessed the advantage of speaking Russian, he was also quite enterprising, he found a farm in the town, arranged for the two of us to stay in one of the rooms on the ground floor, quite a small one but it suited us, and collected a litre of milk every day from the farm and that was really the diet we lived on.

He was convinced, or convinced himself, that his mother was still alive and he was going to find her. He found the existence of women’s camps in the vicinity encouraging.

His misfortune was that he suffered from a suppurating wound in one heel which at the time of our poor state of health anyway, would not heal. My suspicion was that it was a tubercular wound and I hoped that I was wrong.

Child Soldiers and Military Police

We went for a walk through the town and into what had been an official building, it could have been a secondary school now occupied by the military. We met two aspect of the Russian army which have never left me, their military police and boy soldiers.

The military police consisted entirely of women, enormous women, enormous in every direction, intimidating by their very presence made these battle-hardened warriors who had vanquished the Wehrmacht shiver and quake in their boots and sober up instantly.

The other phenomenon were the young boys, I took them to be between ten and twelve, who were dressed in well-fitting uniforms but who also, to our alarm, carried the standard issue Russian sub-machine gun which looked like a small version of the Tommy gun with a circular cartridge drum which I was told later, was a very good weapon

Now it is possible that the guns these youngsters carried were not loaded and more of a status symbol but we were not so sure. It seemed to us that these boys were Russian and Ukrainian orphans picked up along the way and one way of keeping an eye on them was to put them into the army.

At the same time, with equality of the sexes and women tank drivers, etc., why were there no girl soldiers? A third aspect was that the military took no notice of us, they ignored us completely. We were certainly not in as bad a state as the Jewish prisoners found in Belsen by the British and in Dachau by the Americans but we weren’t that fit and well either.

Not only had my stomach shrunk, I had a deep hollow where there should have been one and one could certainly count my ribs. I had lost the digesting enzymes and had very little control over my bowels since I had had no solid food for at least seven months.

Discussing that a few weeks earlier with one of the doctors, of whom we had a surplus, we thought that we had developed new enzymes which enabled us to digest cellulose because most of our intake was beetroot, beetroot is cellulose and the bit of starch in the tiny bread ration wasn’t enough to keep us alive.

Yet we were offered no medical inspection, no food, medicine, bandages, ointment, facility no get clean, a bar of soap would have been welcome. Bread, something we could have digested because we had been receiving small quantities of it during our time in Friedland, was not offered.

It is possible that racial persecution did not exist in the official communist vocabulary, it existed in the unofficial one of course and was practiced, but at the time it felt as if they wished that we did not exist, would soon disappear and not interfere with the view which only recognised a class war to the exclusion of all other forms of persecution.

That may have been a blessing in disguise. Marta Goldberg, a class mate of mine from the Jewish school in Prague, now of Jerusalem was liberated, if that is the right word, with her mother in a labour camp in Poland or East Germany. She had been put on a death march, the guards changed their minds, marched her and her companions back to their camp, meantime there were fewer and fewer of them, and were going to start a march again when Marta and her mother took refuge in the typhus tent, an inherently dangerous thing to do in view of the infectious nature of the disease.

The Germans were frightened of typhus and carried on without them. The Russians arrived, took them to a hospital in Russia but then treated them as servants forcing them to perform menial tasks, put them among German prisoners, refused to repatriate them, made their lives hell, separated them, something even the Nazis hadn’t done and eventually permitted Marta to return to Prague where she joined two aunts who had also returned.

Her mother arrived a year later. Her mother, having now found that her husband and son had perished, became suicidal and their exodus from Prague to Israel was prompted by the need to find a change of surroundings. So, may be, the Russians not taking any interest in us was to the good after all.

The Slide Gauge

While I was disturbing the peace of the countryside, on which had at long last descended, by loud singing, others had put their time to better use. Some of my former fellow prisoners, those from Lodž, had gone back to the VDM factory to see whether anything useful could be organised, the term used until now for the acquisition of food by illicit means.

For reasons I cannot now fathom they thought of me and had remembered, even more astonishingly, that I had been a real Metall-arbeiter inasmuch as I had worked in the locksmith section of the ghetto work- shops.

They returned, looked for me, found me, not easy in the mêlée that was Friedland, and presented me with an 8” long (20.5cm) slide gauge with two scales, millimetres and inches. A slide gauge is a measuring instrument made of steel which enables the user to read off the thickness of metal, the diameter of drills, screws and bolts, even the diameter of a hole, to half a tenth of a millimetre or 1/128th of an inch.

When 18 months later I started work in a toolmaker’s workshop in London I used it every day until I transferred to a drawing office in May 1950, but it has come useful ever since for all of my DIY jobs.

Another aspect of it is that even modern German industry used inches for certain screw threads, e.g. Whitworth. Inches, the Germans used the word Zoll, had been a European standard of measurement until the French metre took over from the French Revolution of 1792 onwards.

Interestingly enough, though the slide gauge is of German manufacture, the embossed maker’s name is “Carl Mahr” of “Esslingen a.N.” (am Neckar), the inch scale has the English “in” embossed at the end of the scale and it may have been intended for export.

The Bicycle

Just before I was ready to leave I spotted half a dozen of my former fellow prisoners standing around and when I joined them they asked me whether I wanted a bicycle. To that was no easy answer. It would have made my travel easier but I didn’t know how to ride one and to learn was risky and a physical strain, I just didn’t have the muscles.

On the other hand I didn’t have the energy to undertake a long walk on foot either and I didn’t know where I was except that it was south of Breslau but that didn’t really help since I didn’t know where Breslau was except that it was in Eastern Prussia and that my aunt Hildegard had come from there. My geography was non-existent.

In the absence of an alternative Prague was my destination though now I had no connection with it, it just happened to be the place from which I had left for the ghetto of Theresienstadt with my parents. Without them I had no tie with that place and the only other place I knew, the place where I was born, Berlin, was out of the question. I was literally rootless.

So I accepted the bicycle. It was a continental type with large balloon tyres and a peculiar method of braking by pedalling backwards, the brake was inside the pedal bearing housing, only of a very small diameter and would wear out soon.

The Journey to the Border

My friend set off to look for his mother and I set off to a definitely uncertain future. This was about a week after the end of hostilities, shooting had stopped. That May was hot and yet I cannot remember what I did for thirst and hunger. Nothing I suppose.

I didn’t need much and couldn’t have coped with it anyway and the nervousness of the journey into the unknown took my mind of such things. I cannot remember how I decided which road to take. I remembered the direction the death marchers and the fleeing Germans had taken and it made sense to follow.

Looking to-day at my copy of a road map there weren’t all that many alternatives. Friedland, or Mieroscow now, is a place where three roads meet. One points to the North-East or towards Poland, one points North-West and into Germany and the third points South-East, away from Prague but into Czechoslovakia.

I took it easy, I could do no other and it cannot have been long, a couple of hours, and I crossed the border, I was in the Republic where people spoke Czech and, in these parts, had been largely unaffected by the war, though I still didn’t know where I was but at least I was getting warm, I had been heading the right way.

More to the point, it was a terminus of a railway line or it was now when a Greater Germany had dis-appeared a week ago and this was once again the border of Czechoslovakia with either Germany or Poland. Before 1938 it had been with Germany, after Yalta it had become a border with Poland except that as yet nobody around there had heard of Yalta.

There were some small locomotives and carriages standing around without any air of urgency, regular service had not been resumed.

The Answer to a Railway Man’s Prayer

I got talking to the railwaymen who sat around idly discussing the latest rumours, I am not even sure whether they had a radio, and it soon transpired that all of us had the same aim, we wanted to travel to Prague.

I did because that was the only place I could think of, it happened to be the place I had left for the ghetto and stations East on 13 July 1943 or 22 months earlier.