Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| ||||||

The Family Brichta Part Four – Auschwitz 13 October, 1944 to 19 October, 1944

Auschwitz

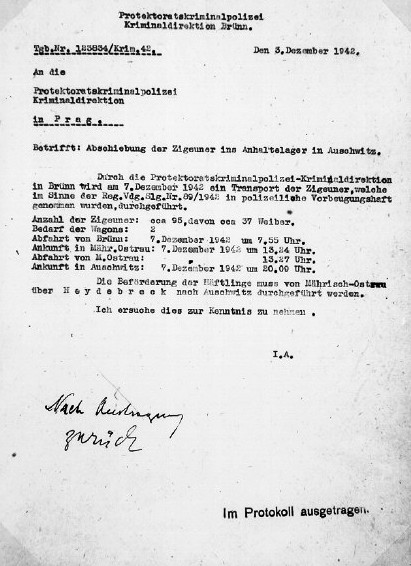

Everybody’s recollection is slightly different. The end was the same. In his memoirs “No name, No Number” Fred Klein, who was deported from the ghetto with the first of ten transports which left in rapid succession, known as “the last clearance of the ghetto”, left on 28 September 1944 with 2,488 others of whom 382 survived.

He mentions travelling in a cattle wagon, or box car for his American readers. Arnošt Reiser in his memoirs “1920-1991” says that he travelled in a third class carriage as my mother and I did. Ernst Sterzer in his biography, in which he describes himself as the only diabetic to survive in German concentration camps, travelled in a cattle wagon and lost his precious insulin when it dropped on the floor between piles of luggage.

Ernst Sterzer’s brother Fred, Fred Klein and Arnošt Reiser all ended up with me in Friedland, but that is rushing things. All three biographies are deposited at the Wiener Library in London. I too have copies.

The journey was dull, our minds were dull, we didn’t know where and what we were heading for and what awaited us. Just as well. The last time we had travelled on such a train had been from Prague to the ghetto of Theresienstadt exactly 15 months ago.

True, we didn’t know what the ghetto was like but at least we knew where we were going and that it would not be far. In their memoirs those who had travelled in cattle or goods wagons complain about the discomfort caused by luggage and not being able to sit and to see out of the only small window.

We in our compartment may have been squashed but we did have a seat and large windows to look out of. Most of the time it was dark, we travelled through the night, I probably fell asleep. Mother probably looked forward to meeting father again but how and what, any new and different circumstances, and they had been separated in the ghetto, must have caused her great anxiety.

Day dawned. We were passing through a dull, flat landscape. And then the train slowed down and all of a sudden we were in a large area defined by concrete posts, wire and wooded towers in the distance.

Some people say that they saw the sign “Arbeit macht frei” over a gate but we saw nothing like it. We couldn’t, we went underneath it. The scene was most odd, weird, abnormal and therefore frightening, certainly not welcoming, just the opposite, something one would have avoided if at all possible. Only it wasn’t possible.

What we saw in the distance were watch towers and concrete posts with horizontal lines, the electrified high-tension barbed wire which became familiar and our narrow horizon for the next 7 months. Then somebody shouted: “This is a concentration camp!”

He was right. Before the war, from early 1933 onwards, Jews had been taken to Dachau, Sachsenhausen, etc. and some had been released on condition that a) they would emigrate, and b) that they would not breathe a word of their experience anywhere. Not all were given the opportunity to emigrate.

Our fellow traveller had been one of those. He recognised the trappings of such a place alright. There were groups of men in the distance as well as close by, and SS-women. I had seen plenty of SS-men even in pre-war Berlin in their black uniform, riding boots and caps with an embossed skull in dull metal finish, but never women and these women had walking sticks and looked aggressive.

Now the large window of our compartment was fixed but it did have a sliding ventilation window. Suddenly some frighteningly emaciated faces appeared under the window and shouted for bread to be pushed to them through this ventilation window.

Opposite me sat an old man and his daughter, they had brought with them plenty of bread. They considered what to do. There wasn’t much time for that. These thin people in prison garb with a haggard look were obviously stepping out of line from where they had seen our train and it was clear from the urgency of their voices that they were taking risks and were driven by desperation caused by hunger.

The old man decided against pushing a loaf, or part of it, through the ventilation window because if the situation was that bad then they, he and his daughter, would need all the bread themselves.

This picture has never left me. From it I have tried to learn and put into practice that if one sees a need and is in a position to help then do so right away, one may not have the chance to do the good deed later. An hour later, at most, this man was dead, the bread and everything else he had possessed, he had to leave on the train from where it was collected and taken to Kanada.

The train came to a halt, the seal on the door was removed, we were ordered out. Others remember the shouting, screaming, threats, whips being brandished, snarling dogs. Nothing like that occurred at the arrival of our transport, there was no need to.

Obviously there was utter confusion, but trusties, prisoners doing the dirty work for the SS, not that I blame them, everybody clings to life and this particular lot hadn’t done it then others would have. Surely the blame for the system rested squarely on the SS and the German people who supported this way of life, or death, one can hardly blame it on the victims. These trusties, for want of a better word, put us into two long columns, one made up of men, the other of women, some six abreast.

As there were 1,500 of us then there must have been two columns 125 persons long, quite a length, it didn’t take long to form, the prisoners who got our long column into line had done this before. There was a wide gap between these two columns, enough for a truck to pass through.

The trustee prisoners or the SS, I cannot remember which, asked whether there were any blind, lame infirm or sick who needed a lift into the camp. Those who felt that they answered that description stepped out and were helped up into the rear of the lorry. At the time I thought that it was a rather decent act to help the old, blind and infirm but I soon learned to suspect any such outward sign of civilised behaviour.

The scene was in contrast with that Ernst Sterzer witnessed four days later when he records that SS-men killed infants and small children by grabbing them by their legs and hitting their heads against the train still standing in the siding. He saw one of them throw a blind man to the ground and kick him in the head till he was dead. That was another shift. With us they achieved the same result without such terror tactics.

In the melee of leaving the train and being put into one of the two columns I became separated from my mother. Anyway, my mother was in the column to the left of mine. Both of us were near the front of each column. As always, I was a bit slow, was overwhelmed by it all and didn’t see my mother but my mother saw me. She left her place in the column, walked over to me, shook my hand and returned to her place.

Her column went forward first, one at a time until one came across an SS-officer with several assistants either side of him. I couldn’t see exactly what was happening but some of us went to the left and some to the right. I had seen my mother go to the left.

It didn’t seem to take all that long for the left column of women to be processed and then it was our turn. I was, as I said, near the front and when it was my turn I walked forward until I got to the SS-officer in charge. According to the accounts of others he would look at one, just for a second, the process was quite quick, and indicate with his finger where the person in front of him was to turn. I can’t remember any of that, I didn’t take that in. I had seen my mother go to the left and so I simply turned left too.

I was called back. Obviously the officer’s assistant had watched his finger and saw it point to the right even if I had not. So I was called back and told to go to the right. I had been chosen to live or rather, not so much to live as to work and to work until I died of exhaustion by which time I would look like the prisoners who had asked for bread about an hour earlier. It was really a postponement.

On the right I waited for further directions with the others who had also been told to turn right. There weren’t many of us. From records I now know that out of our transport of 1,500 who left the ghetto of Theresienstadt on 12 October 1944 only 78 survived. Of course, a few more may have survived this first selection and died, or were put to death, later but there were very few anyway. Say that there were 90 picked to work of whom 50% were men, then there were 45 of us.

Also with hindsight, i.e. from the list of prisoners transferred from Auschwitz to Gross-Rosen, the central Silesian KZ of which Friedland was a branch, I know that the manager of VDM in Friedland had asked for 165 slave labourers from a transport from Theresienstadt because 165 slave labourers were delivered but that number had to be made up with prisoners from other transports, from Theresienstadt, who had arrived up to two weeks earlier (Fred Klein) or a week earlier (Arnošt Reiser) , and a few days later but before our departure on 19 October, and with Slovak, Hungarian and Lodž Jews.

Before continuing there are some more statistics culled from the above mentioned list. Rumour has it that Albert Speer, the armaments minister who unfortunately was not hanged at Nuremberg, had asked for more slave labour and that the ghettoes of Theresienstadt and Lodž were the source of that labour. The figures don't bear that out. What they do bear out is that Mengele, or the Auschwitz organisation as a whole, continued with their policy of full-scale extermination.

True, Germany's aircraft production had gone up from 24,800 planes in 1943 to 44,000 in 1944, or five times the 1939 figure but Speer was able to do that without any of the hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews of whom only a few were used as slave labour, nearly all of them were murdered at Auschwitz.

Likewise the manager of VDM had asked for another 165 workers in addition to the 300 he had already received five weeks earlier but we were not in addition to the existing workforce so as to increase output, we were substitutes, cheap substitutes, because the French and Czech workers whom we replaced were sent home two weeks after we arrived and they had shown us the ropes.

VDM had a contract with the German Air Force to produce the propeller blades for the increased number of fighters and short-range bombers. There were 1,500 people in our transport, say 750 men and 750 women in all ages ranges, from the very young to the very old. 165 is only 22% of 750.

From the list, of which I have only a poor copy from the Gross-Rosen Museum in Poland, I could decipher 134 dates of birth. In October 1944, when transport Eq arrived from which the prospective VDM workers were to be selected, the youngest was aged 14, the oldest 52, a wide range from which it should have been possible to find 165 fit men and boys. Yet the average age was 33 years 5 months, 49%, or nearly half, were aged 35 to 52 and 75% were aged 27 to 52.

That means that most of those most likely to be fit, those from 16 to 26, represent only 25% of the total and that means that the majority of the young and fit were destroyed on arrival and were not made available to the German war effort or to posterity.

Those 45 or so who had waited until the whole of our transport had been selected one way or another were now marched to the next stage of the process, taking our clothes off thereby losing our last shirt, shower, shaving off of all hair on our bodies and the issue of prison garb which in our case was not the striped clothing.

On the way to stage one the SS-soldiers asked us for watches. They were quite polite about it, they just said we weren’t going to need them any more. They, of course, knew better. Once taken off and put on one big heap they were out of their reach. Some of us handed them over.

We had to wait outside one of the large halls, women were still inside who had been shorn. A door was open and we looked in. I had never seen a naked young woman but these beings looked utterly and completely like the shop window dummies, deprived of all sexual appeal, which I had seen.

Except that is for the “shearer”, one could hardly have called her a hairdresser since her job was to get rid of all feminine tresses. She had a full head of wavy black hair. Odd, since one of the reasons for removing hair was to deprive lice of a foothold. Lice lay eggs on human hair and lice carry the typhus bacillus which is no respecter of person and the Germans were frightened of typhus outbreaks.

Once we were inside we were told to remove our clothes and put them on a pile, or piles, except for shoes or boots which were retrieved. That made sense, we were earmarked for work, some, like us, within the jurisdiction of other main camps, KZ Gross-Rosen in our case, it was winter, we would need shoes to move and work more efficiently and, since everybody had a different size shoe, it best to keep them.

That is a generalisation. I was to lose my shoes inside the camp and there are stories of others who had to walk to work barefoot and were lucky if they had rags to tie round their feet. What struck me then though was the order for all those with surgical trusses to support their hernia, to put them all on one pile. That did not make sense. Having selected them, admittedly on outward appearance, on Dr. Mengele’s hunch, and having got them this far, to deprive them of their trusses would soon make them unable to work

Different people describe the next steps in different sequences and I can’t remember. Did we have our hair removed before or after the shower? I don’t know. Reiser says that it was done professionally and that his crowd was painted with carbolic to disinfect any cuts. That is not what I remember.

By the time it was my turn, and I was very hairy, the barber’s safety razor was very blunt although there must have been plenty of replacement blades as every arrival would have carried a supply, he did a “dry” job and it was painful to have all hair removed from chest, legs, arms, arm pits, testicles and anus.

I cannot remember the carbolic at all. Then there was the short shower, I can’t remember whether we were given any soap, just a rinse would not have removed any dirt. There was nothing to dry oneself with, exposed to a Polish winter’s blast at an open door one would normally have caught pneumonia. There was nothing normal about our situation and we didn’t.

Then came new clothes, a misnomer. Reiser says that there was a deliberate mismatch of sizes but I can’t remember that. Underpants were short, wide, ill-fitting and tightened with string. They were made from prayer shawls. That may have had its root in wanting to insult the Jewish religious procedure but as they were made of the finest wool it did us a good turn. I received no shirt, instead I was handed a thin blanket to wrap around me and to tuck into the trousers.

The trousers too were ill-fitting, made for a short but wide man and held up with string. The jacket was black, very old, had been worn by many others who had probably died in it, disinfection by steam had made the fabric brittle and a very large cross had been painted in red paint on its back. Exposure to the elements had made the paint brittle, bits had fallen off. Each of us was also issued with a cap, for the doffing of, the most important part of our used or second hand attire.

We were then marched off to an empty wooden hut, or block, but before we could enter we had an extended period of instruction by the Blockälteste on the removal of our hat, or beret, with a flourish, to be carried out whenever an SS-man of any rank approached, as a sign of deference. There was also a knack in putting it back on again, this too had to be done quickly and pulled to one side, it was not to sit centrally on one’s head like a yarmulke.

We were then let go but warned not to go too far, if there was a roll-call one had to rush back to the block to which one had been allocated. If taken short and one found oneself in a strange block and there were more in that block than its allotted number then the surplus would be killed.

A preferred method by some Blockälteste/senior of a block or hut, or of kapos, another grade of prisoner endowed with unlimited powers, was to put a spade across the unfortunate’s throat and step sharply on the spade thus severing the head. Gruesome but quite possible.

I didn’t stray far, it was dark outside by then apart from the gloomy light given of by the bulbs attached to the concrete posts with bent tops to which the barbed wire was attached. The wire was actually attached to porcelain insulators. It was the insulators which were attached to the posts. The insulators were necessary because of the high voltage in the exposed barbed wire. I saw just one man in the wire, his body twisted by the electric shock. Presumably he couldn’t take it any more.

I didn’t have far to go or to look to see the squat rectangular chimney belching black smoke. By that time I had heard what had happened to those who had been directed to the left by the moving finger. I stood there by the flickering flames licking above the top of the chimney and thought to myself: “which of these flames is my mother?” but not feeling the immensity of the loss, the slaughter of innocent blood who had thought of herself as German until 1933, had played her part for Germany in the 1914-1918 war, had given gold for an iron ring in support of the Kaiser’s war, had been proud of her brother in the German navy, the Kriegsmarine, being awarded the Iron Cross and who knew and had said so on many occasions that Hitler would not let her survive the war.

It did also occur to me that my father, who must have arrived at the very same place a fortnight earlier, would have suffered the same fate and that I was from now on my own and quite unprepared for that, but I didn’t cry or had strong feelings. The automatic mechanism of self-preservation, the shutter to feelings which could hinder that had already come down quite firmly and the numbness with which one confronted this valley of the shadow of death where there was no comforter took years to lift.

When I returned to my hut we were all assembled in a corner next to the door, a wooden box was pointed at us, we were told that it was an X-ray machine and would we voluntarily hand over any weapons found on our person.

We may have been confused, downhearted, miserable, frightened and some were now deeply concerned about siblings, parents, wives, girlfriends, relatives, etc. but we were not stupid and to be treated as if we were was just annoying. I did however find a horseshoe sewn into my new old jacket which was removed. I suspect that it not been sewn in for luck but at heart level to protect the previous owner from blows, i.e. it would have spread the impact.

The first night was horrific. There was a rendered brick heating duct running the length of the hut, something like 1m high and 1.5m wide, dividing the hut into two and, while these huts had been stables for horses, which is what we assumed they may have been, that would have been a heating duct but of course now it was cold as was the concrete floor on which we had to lie with a thin blanket over something like five people.

What kept us awake and disturbed us were people coming in inspecting our shoes. On the other hand we were not permitted to leave the block at night and had to relieve ourselves into a huge tub or wide half barrel with two holes through which a wooden rod, like a broomstick was passed. Unfortunately I and another fellow were ordered to lift it and carry it to the cesspit and empty it. As it was full to the brim spilling was unavoidable and some of it went over us.

The next day we were told by our Blockälteste, or hut elder, that we were very lucky indeed, a good job in a factory was waiting for us and that we would be leaving in a few days’ time. While we didn’t know what he was talking about, what he really knew, how reliable it was and seeing is believing it sounded good, anything must be better than this hell hole.

That wasn’t necessarily true, the Germans had plenty of other hell holes, Friedrich Flick’s mines and munition factories, Dora Mittelbau where V1 and V2 rockets were being made and life was brutal and short are examples but as it turned out in our case he was right, that did not mean that some of us weren’t going to die at our as yet unknown destination.

We also experienced our first Selektion, another inspection of the state of our bodies, a daily routine, carried out by Dr.Mengele or a deputy. Having been passed as fit at the so-called ramp on arrival did not guarantee future survival. If one’s ribs started to show through the skin one was taken to a hut and from there to the gas chamber. A Selektion was an unnerving experience.

As we realised some time later we had not been tattooed because only those who were to stay and work within the Auschwitz territory or boundary were thus marked. The property in our bodies had been pre-destined, probably before we even had left the ghetto, to pass to the jurisdiction of another KZ and it was that other KZ which was to number us. That is why Fred Klein called his story “No name, no number”, we had lost our identity by name and a number had not taken its place.

Because we were in transit we had nothing to do. On my walks, always within easy return to my hut, I was once spoken to by a more permanent inmate, which in a way was a contradiction like so many things there, in striped garb though I can’t remember what small coloured triangle provided a clue to his category, we had not been told anyway, it could have been a homosexual, it could have been a murderer, he was not a Jew.

He was German and enquired where I had come from and when I told him he ask whether we were “anständige Leute”, decent people. I assured him that we were indeed “anständig” such a virtue seemed out of place there where the exact opposite ruled, but then it was just small talk.

My perception of what went on had not been completely deadened. Once I saw an elderly man being beaten by a young kapo and felt terrible. There were other, less traumatic yet odd sights, like Russian prisoners of war. They must have come from a particular region because all of them had the same features, fat necks, just like the cartoons depicting German bureaucrats. What were they doing in an Auschwitz transit camp?

As I learned much later Russian POWs were treated abominably, millions of them were starved to death in open enclosures. Here they seemed to be doing well and not subject to Selektions for the gas chamber, which they would have passed anyway.

Permanent occupants, if that is the right word for a transient hell, also had a far more comfortable stay if, so I was told at the time, they were artists. Painters were treated generously by the German guards and officers in return for having their portraits painted. There was one Czech female artist who painted Gypsy girls for Mengele before they were gassed.

The second night proved crucial and also proved that the forecast about our future had been correct. It was dark, that could have been as early as afternoon, it gets dark early in October in those parts, when we were told to stand along one side of the raised central platform or heating duct which divided the hut for no apparent purpose.

The door near us opened and a civilian with a couple of SS entered. The civilian wore the outfit which marked him as a Nazi party member, a light gabardine coat with the round party emblem in his lapel. The light was dim in these huts and even when the eye got used to it one couldn’t see well and far, but it seemed that he was looking at us from a distance and then pointed his arm towards individuals as if closer contact would be distasteful, if it had to be done it had to be done from a distance.

That was it, we were being chosen. Those who had been pointed at then crossed the brick heating duct barrier and assembled at the party member’s side. I happened to be close to the door and when it was my turn to be pointed at I seem to remember actually jumping across. There were two hitches. Firstly there were not enough of us, Dr.Mengele had not played the game.

The man in the raincoat was undoubtedly the manager of VDM of Friedland, Southern Silesia, formerly of Hamburg, who had been promised 165 Jewish Metallarbeiter, skilled workers in metal, and there was only a quarter of that number to chose from, but we didn’t know that there should have been more of us.

Secondly, he had also been promised a mathematician. The reputation of Theresienstadt as a never ending source of intellectuals must have permeated German society so that by their reckonning there must have been at least one mathematician even among the few to come out alive after Dr.Mengele had done his worst (he had 95 out of every 100 gassed on arrival).

In fact these last eleven transports which left Theresienstadt in quick succession during October 1944 contained most of the many of the ghetto’s musicians, composers, painters, poets, film makers and doctors and doctors who were also musicians and cartoonists (“Art & Medicine in Ghetto Theresienstadt”, the Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, the Technion, Haifa, 2001), of whom hardly any survived.

The reputation had been a deserved one, there had been a concentration of intellectuals, very nearly all of the place and date of death on index cards bearing their name is Auschwitz-Birkenau, October 1944.

What the manager of VDM really needed was a technician who would find and list the properties of each propeller blade using the apparatus provided so that when three or four blades were to be fitted to a hub of any one engine their eccentricities would cancel out and there would be no resultant vibration.

To use a mathematician for such work was rather a waste of talent but then if you could have the best of Jewish expertise then why not go for it, the cost was the same. However, when asked, no mathematician raised his hand.

That was a grave disappointment to all, may be the Auschwitz system of providing German industry with Jewish labour of every skill imaginable wasn't perfect after all. Later, in Friedland, when the German Air Force asked for an electrical engineer merely to operate a spot-welding machine they got a professional engineer who pre-war had been in charge of an electricity generating station.

However in our present, or the manager’s predicament, the Auschwitz reputation was saved. One of our group remembered that one of us had failed the Selektion that morning and was in another hut to be taken to the gas chamber when they had a few minutes to spare and that this unfortunate being was a mathematician.. A messenger was quickly sent to that hut of the condemned and the man was reprieved.

Looking at the more legible copy of the first page the first 19 names, from No.73801 (Buys) to 73829 (Voticky) there is a variety of trades. Number 73803, that’s me, claims to be a Schlosser, a locksmith. There are electricians, joiners, mechanics, a car mechanic, no fewer than three doctors (Artzt) and one Matematiker, No.73806, Otto Fischer, born 03.08.1909.

I knew Otto Fischer vaguely from Prague, he had also worked, as my father had done, in one of the many departments of the Ältestenrat and his name can be found on p.411 of “Die Juden im Protektorat von Böhmen und Mähren” published in 1997 by Maxdorf in Prague, Czech Republic, copy in British Library and Wiener Library. He is listed under “Statistische Kanzlei” (statistical department) Fischer Dr. Otto, Vorstand (head of dept.). I got to know him a bit better in the ghetto where he had taught four of us mathematics once a week. He had been a naturally thin type and that had worked against him.

The Numbers Game

To us the worst was over, we were going to leave, we had been told that it was going to be good, anywhere must be better than this, we could bear a few more days until the German railways could find a train to take us to our destination.

We didn’t know where that was and even once there I didn’t know where I was. Trains were probably no problem, one of those which had arrived crammed full with gas chamber fodder would take us, the real problem was to find enough to make up numbers.

As already explained, an insufficient number of men had been allowed to survive on arrival. The next transport from the ghetto, Er, which left on 16 October 1944, fared marginally better, 117 out of 1,500 survived, or, say 58 men. That, added to our 39, still didn’t add up to the 165 needed or asked for by the factory’s manager.

According to the list of prisoners transferred from Auschwitz to KZ Gross-Rosen, of which Friedland was a branch, several former inmates of the ghetto of Lodž, and some Slovak and a few Hungarian Jews were added. That was something I had to wait for another 60 years to find out.

As mere nobodys we didn’t know what went on behind the scenes. At the time we didn’t even know that not being tattooed meant that we were destined to be shipped out of the Auschwitz jurisdiction and I didn’t know that some prisoners were tattooed.

Clogs for Shoes

Auschwitz had not finished with me yet. If the prospect of an early departure had given rise to a hope of better surroundings in the not too distant future then I had not reckoned with my fellow prisoners in the here and now. The Blockälteste of the hut next door was a relative newcomer. It was quite remarkable how quickly scum rose to the top. He too had worked for the Ältestenrat in Prague as a clerk, which was such a large employer of labour because the Germans were very keen to have an accurate forecast of the loot awaiting them once the owners had been removed, first to the ghetto, then to Auschwitz. I recognised him.

Most of the work there was cataloguing the returned property lists which every member of a family in the Protektorat and in the Reich had to complete, i.e. husbands as well as wives. I have been unable to trace ours but that of my uncle Fritz in Berlin.

The man in question was not a native of Prague but of Ruthenia, the eastern most part of the sausage-shaped Republic and now part of the Ukraine. I tried to get near him to ask whether he had seen my father but I never managed it, people in such elevated positions were unapproachable.

Just as well, it is better to believe that my father was gassed on arrival, not knowing what it was all about until the last minute than to survive the Selektion on arrival and know what lay in store. This boss had a sidekick who was of my age, also came from Ruthenia, or the sub-Carpathian Ukraine, its official Czech name.

I had the misfortune to come across him on two more occasions after the war. This time he took a liking to my shoes. We now know that there were mountains of shoes taken from the dead but that was in the Kanada section and possibly meant for shipment to Germany and it was not for use by prisoners. Good shoes, preferably boots, were important because snow and ice played havoc with leather one couldn’t treat.

My shoes weren’t perfect, they had been made to measure in Prague but I had grown and they were really too small but they were leather ones. In Auschwitz one didn’t argue when he wanted them but I pointed out that I needed something on my feet.

That hadn’t occurred to him but he did come up with a pair of wooden clogs, standard Auschwitz issue. Not clogs in the Dutch sense but a solid piece of wood as a sole with a fabric top which, of course, was not waterproof, and string as laces. Because the solid sole didn’t flex these clogs were uncomfortable and gave me flat feet, to which I inclined anyway, and that in turn affected my posture.

Later, in Friedland, marching on an icy, slippery road in them in step they provided no grip and to prevent one from sliding consumed a lot of energy which I didn’t have to spare.

On the appointed day, it was 19 October 1944, we were marched to the sidings, this time it was a cattle truck/box car for us, given a ration of bread, and stuffed, literally, into the cattle truck, standing room only. To start with at least we didn’t mind, a small price to pay if it took us away from the smoking chimney stacks. The train rattled along all night.

At some time in the morning , we had no idea what time it was, we stopped, the doors were slid open, the sun shone in, we were ordered out onto a platform of a small town railway station. I had stood in a dark corner and didn’t know what had been going on. Others, like Arnošt Reiser who had been close to the one small ventilation window says that we had stopped at another Friedland, now Frýdlant and in the Czech Republic and close to what is now Poland, where they hadn’t expected us and that the train driver had to retrace his steps to deliver his cargo of slave labourers where we were expected.

Arranged into a column five or six abreast we were marched to our new abode.

Sources: The unpublished memoirs of Frank Bright – Selected extracts used with full permission. Dedicated to Hermann and Toni Brichta – Both murdered in Auschwitz "Produced by Chris Webb" Online version: Copyright H.E.A.R.T 2008

Copyright. Frank Brichta H.E.A.R.T 2008

|