Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team |

|

Survivor Stories

Holocaust Survivors Chelmno Survivors Righteous Gentiles Holocaust Recalled

| ||||||||||||

The Family Brichta Part Three - The Ghetto of Theresienstadt 14 July 1943 to 12 October 1944

Arrival

We had left the assembly hall buoyed up by the news of the Allied invasion of Sicily and arrived in the ghetto on 14 July 1943. Our transport was luckier than previous ones had been. To hide the arrival and departure of trains the Germans had made 300 inmates build a spur line from Bauschowitz, the nearest railway station, into the ghetto which had been completed on 1 June 1943, six weeks before our arrival.

Until then the tens of thousands arriving and the tens and thousands leaving (50,871 to be exact) had to carry their luggage to and from that station, a distance of 2.8km or 1¾ miles. As every transport was a mix of toddlers, the young, the middle-aged and the old it can only have added to their distress as did the presence of the SS and their dogs.

We were fortunate, in that respect at least, and alighted inside the ghetto though, naturally, we didn’t know where we were, it took some days to orientate oneself even though the place was small.

First Impressions

A great many others have already written about the ghetto and I shall confine myself, as far as possible, to my impression of it during my time there, some 15 months. It changed throughout the four years of its existence. Had we arrived earlier we would have found some of its original inhabitants still there and the inmates were confined to their barracks

By the time we arrived they had all gone, expelled would be a better description, to make room for more and more Jews and, until the hour of the curfew, one now had the run of the place. Before we arrived the Germans had taken a more hands-on approach, some inmates had been hanged in public for instance.

By the time we arrived the conversion of the old military barracks into more densely populated dormitories with at least two storey, sometimes three storey bunk beds had been completed, together with very primitive and insufficient washing and toilet facilities and the same applied to the terraced houses with their courtyards which, as I said, had been vacated.

Public showers were in operation though access to them, by ticket, was far too limited. Workshops, kitchens, hospitals, local surgeries, bakery and butchery all had already come into existence and the ingenuity of Jewish architects, civil and public health engineers, some of them turned tradesmen, and skilled tradesmen at that, must be emphasised. Even so they could only ameliorate dreadful overcrowding.

Another, German inspired, innovation had also taken place. This was to be a show ghetto to be shown off to the German Press and to the Swiss Red Cross and, as both were willing and eager to be deceived it was a success, from their point of view anyway. Shops had been opened even if the most urgent and needed item, food, was not for sale whereas shoe polish was.

There was a library stacked with books which had been stolen from Jewish homes. I remember reading a German translation of Churchill’s “History of the First World War” and felt reassured that the British, with the support of the Americans and American industrial muscle, would once again win the last battle. They did though by that time there were not many of us left to see it.

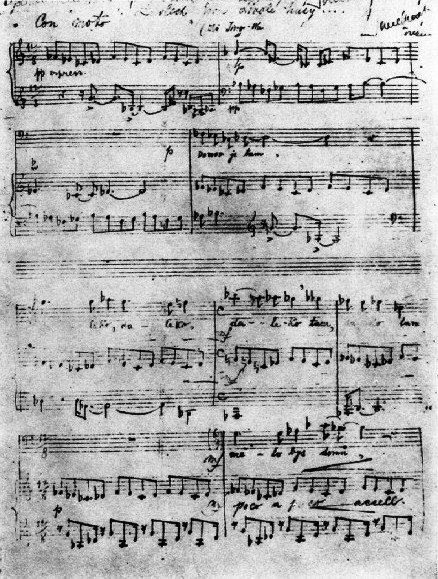

Lectures on every conceivable subject, science, history, literature, archaeology, etc. flourished even if the attendance was sparse. New operas, operettas, children’s operas were written, produced, performed, even if to small and changing audiences. Lieder by Hugo Wolf, Beethoven and Dvořák were sung, Verdi’s Requiem performed and yet all of that passed me, and many others, by.

That is just one aspect of it, the other one is that the intelligentsia, suppressed by the Germans, burst forth for the last time having been given the chance. By the time we arrived there was a Ghetto bank and ghetto money but what good was it except to give the entirely false impression of normality on which, nearly 60 years later, the prospects of a German ghetto pension is based. German propa- or improper-ganda is still very much with the now elderly former inmates.

When we arrived there were what one calls to-day two parallel universes. There was terrible overcrowding, a complete absence of privacy, hunger, the old, and therefore not working, dying of it, a constant fear of being put on the next transport East into the unknown from where no traveller had as yet returned, odour, bed bugs, typhus epidemics, separation of husband from wife, children from parents.

The sense of right, equality before the law had gone out of the window a very long time ago. And there was class distinction which formed part of our existence. There were Prominente who had far more living space, spouses living together, and there were Mischlinge, both categories being protected from the dread of transportation.

The other co-existing universe consisted of recitals, lectures, plays, painting, much of the latter illegal all based on knowledge, training and education and dedication acquired in a previous existence, a cafè with a band, a bandstand, a bank, shops, a post office for those fortunate enough to receive food parcels and post cards underground newspapers by children for children, which did not sit easily with the equally real first universe. The place was unreal and yet real enough.

The First Few Days

Mother

Having arrived and still confused, where do we go? Obviously, or it became obvious that nothing was left to one’s initiative, one didn’t go and look for “suitable accommodation”, something one had got used to since the German occupation of over four years earlier, one waited to be told.

Although I cannot remember the name of the barracks (Kaserne) to which my mother was sent, it doesn’t really matter, they were all the same, had been designed and built at the same time, were built of the same materials, looked the same, had the same details, stairs and rooms off a wide corridor, after all they had been built for 18th century soldiery whose lives were poor, nasty, brutish and short, so nothing new there.

There she was allocated a place on a two-tier bunk in a room, more like a hall, of identical bunks closely spaced, with no room to put anything, as far as the eye could see, or that was how it seemed to me. Even the sight of it was overpowering..

This very crowded place must have come as a terrible shock to her. My father had been a soldier and a prisoner-of-war for many years, six to be exact, and had experienced such very basic conditions before, even if that had been 25 years earlier. I was 14½ and flexible as well as phlegmatic, my emotional resistance was beginning to bite, to take it all in and bewail one’s fate would have been fatal, resilience was the order of the day and one would have to call on that attitude frequently, getting upset wasn’t going to get one anywhere but would affect others.

For my mother there had already been a severe reduction in space from our Berlin apartment to a small one-bedroom flat in Prague, but that at least had been hers. She never left that flat for the last four years. There had been nowhere to go, there were no walks, no parks, the latter closed to Jews anyway. Having come from Berlin she didn’t know a soul in Prague and the flat was her refuge, her island without a sound, there was no traffic, no radio and no gramophone. The radio had been handed in soon after the occupation and the gramophone had been left behind in Berlin, together with everything that was of any size.

That hall, or dormitory in one of the ten Kasernen was the exact opposite to what my mother had been used to. Overcrowding was not just a matter of so many people per square yard but was a matter of the old, elderly, middle-aged, every one of whom could disturb the peace of the rest by snoring, coughing, sneezing, crying, whimpering, talking in their sleep, getting out of bed, getting into bed, scratching (there were bed bugs), passing wind, arguing whether the window should be open or shut or even dying.

Father and I

As the place was overcrowded father and I were sent into the loft of one of the Kasernen the name of which I cannot remember, it could have been the Magdeburg or any other.

The advantage, if any, on being in the loft was that there was plenty of space, on the other hand it had never been intended to be inhabited. I don’t think that one would have fallen through what was the ceiling below, that had been boarded, but one had to climb over enormous timber beams spanning the width of the large building, beams of a size one doesn’t see nowadays. Electric light was only sparse and of very low wattage.

Toilets and washrooms were on the floor below and were also used, of course, by the inhabitants of the floor below, so it was highly inconvenient and insecure, while out at work anybody could come along and pinch things, it was open plan at its most extreme with a bit more air than anywhere else, in winter there would have been too much of it.

The Schleuse/Sluice

What we had not reckoned on was that our belongings, one large duffle bag each, would be kept from us, would be kept and searched in the “Schleuse” (sluice or lock) through which they had to pass, and those carrying out, the searchers, reputed to be German women, took their time over it. Meantime all we had what we stood up in. It was July and very hot. It added to our sense of complete insecurity.

The First Day

I remember our first day. We met in the courtyard of the Kaserne to which father and I had been allocated and had queued up for our first meal or ration. As one had no eating utensils, they were in our bag, it was just as well that it consisted of plain boiled potatoes in their skin, not that many of them and they hadn’t been cleaned that well either.

So shortly after arrival we still had the basic standards from the previous world but we soon learned to disregard them, this was not the place to be squeamish. We were however also surrounded by old people who realised we were new to the place and therefore with some out-of-place attitudes and they begged for these potatoes. It was a pitiful sight.

There had always been beggars about, more so in Berlin than in Prague, and even selling matches or shoelaces was begging by other means, but these were really heart-rending, these were our people, reduced to the lowest possible level. So we gave them our potatoes but it was the first and last time, now we had gone without them and were hungry.

The way of the ghetto was that the Germans considered old people, particularly Jewish old people, as merely “useless mouths” and the calorific value of the food allocated to them was worked out so that they wouldn’t live for long on such rations. And neither did they. Of the 73,468 people sent to the ghetto from the Protektorat 6,152, or 8.4% died in the ghetto and I am quite sure that these were the old ones.

For the 42,921 people from Germany the figure rose to 20,848 or 48.5% and for the 15,244 sent from Austria it was 6,228, or 40.8%. The high incidence of deaths of inmates from Germany can be attributed to the starvation they had endured over the years before they were sent, Jews received far lower rations than Germans doing the same work and because they were elderly and on a, literally, starvation diet. My aunt Helen Koppel died a few weeks after arrival from Berlin.

If you were too old to work your prospects were bleak, death by starvation is slow and the worst way to go.

The Second Meal of the Day

To live you had to work, or do something that fitted in with the scheme of things devised by the Germans. Thus carpenters, fitters, tinsmiths, electricians, plumbers, smiths, nurses, cooks but also musicians, lecturers, players in a band, once the Germans had decided to encourage them to suit their own purposes, were considered to be working and that meant another meal at the place of their work, e.g. at the vegetable garden where I worked temporarily, or the locksmith workshop where I settled down, meant that only those working were getting this additional food.

The calorific value of that supplement was worked out to enable a worker to work, or to live and work, but only just, one was always hungry.

Before Starting Work

Once we had our duffle bags, which contained our sleeping bags, I settled down for a while next to father in the loft. We hadn’t been absorbed by the bureaucratic system yet and I used the time to read organic chemistry.

That may sound odd but that was what interested me. It was one of the many subjects not taught at my school. I had had the chemistry kit at home but wanted to know more, much more. Gottfried Bloch, the young doctor from the ground floor of the block of flats where we had lived had given me his two college chemistry books, one on organic and the other on inorganic chemistry and |I had taken the book on organic chemistry.

May be I should have taken another pair of shoes instead but I didn’t have any, or another towel or shirt or woolly to fill the space with in the duffle bag, but I took Gottfried’s , or Friedel’s, chemistry book, probably in the optimistic frame of mind that where I was going to land there would be an opportunity to read it.

Hope springs eternal.

Starting Work

The opportunity didn’t last long, the system caught up with me and I was ordered to move to the floor below where a place had been found in a youth room or dormitory, for want of its proper description which I can’t remember.

The idea was simple and commendable, adults and young adolescents should live among their own kind. As an only child that was a new experience but I took to it, crowds have never bothered me, and there was no option anyway. Nevertheless, as I realised in later years, there was an adverse sub-conscious reaction, I didn’t get up on time, I resisted, or at least postponed, having to face the outside world.

The routine was that one got up, washed, however perfunctorily, in the washroom, got dressed, had what was called coffee and a piece of bread if left over from the previous allocation, and rushed to the labour exchange. At the labour exchange vacancies were allocated by their desirability on a first come first served basis.

Desirable jobs were obviously those connected with food, its preparation in one of the many mass-kitchens and its distribution. As already mentioned, the meals for the working population was delivered to their places of work although some places collected their allocation themselves, about that later.

There was also the bakery and the far smaller butchery. As I would not get up with the alacrity clearly required and in one’s own interest I ended up with the less desirable jobs. On the other hand there were few desirable jobs simply because they had already been taken.

The last large- scale transports, 7,000 people in five transports at the end of January, all to Auschwitz of whom 96 survived, may have created such vacancies but there had been six months to fill them and Mischlinge in such jobs would tenaciously hold onto them because they were exempt from being sent East.

Desirable could therefore mean what you would have liked to do rather than what was left. Thus Gottfried Bloch was keen on anything to do with doctoring and Arnošt Reiser was keen on anything to do with chemistry and indeed he ended up in a laboratory and distilling alcohol for the German administration as a side line.

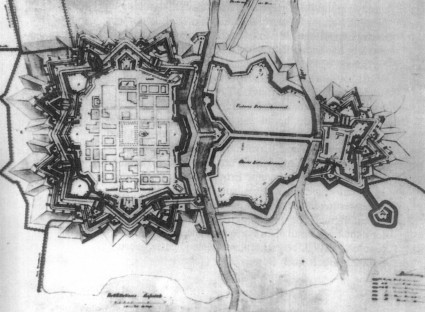

My first job was in the vegetable garden outside the ghetto and the second one in the workshops within the thick walls which formed the outside of what had been a fortress garrison town built to the then latest fashion in fortifications by the Austrian Emperor Joseph II and named after his mother, the formidable Maria-Theresa, whose coin, the Taler became the Dollar and who had experienced at first hand Prussian aggression unleashed by Frederick the Great, an equally formidable opponent, by the two Silesian wars when he perfected the habit of keeping the winnings.

From then on Prussia never looked back or changed her arrogance and views on her own superiority and we were victims of that attitude and, if you were historically minded, the ghetto reminded you of what had started 200 years earlier.

Although I had worked on a vegetable garden in Prague and had liked the work there I didn’t take to the one in the ghetto. There could have been a variety of reasons, one was that I wasn’t impressed by the gardening of which I knew something after all, a more pertinent reason was my hayfever. Ever since I can remember I had suffered from it and looked forward to winter, or to neither summer nor winter. Antihistamines were not available then, even those with side effects such a severe drowsiness were not to become available until 1950, those without side effects, at first of the cortisone type, not until 1967.

Then I just sneezed, produced copious volumes of mucus, had inflamed eyes and it affected my ears as well. I always searched for shade because sunshine made me sneeze even more and working in the open was not the thing to do.

Sinusitis

In the ghetto, even working inside a cavernous workshop, I had sinusitis twice. The hollow parts behind the forehead had become inflamed as a result of my allergy to nearly everything growing, from trees to grasses, weeds to shrubs and had to be rinsed clean.

There was a surgery accessible from the courtyard behind where I eventually settled down, L418, and to this day I remember sitting down, facing a stern no-nonsense ENT surgeon who told me in no uncertain terms that if I didn’t keep my head absolutely still he might push the rather large needle into the eye nerve running close by. I kept very still and felt the honeycomb-like bone structure being crushed as the needle made its way through it into the cavity.

Then warm water was pushed through a tube attached to the needle. The water flushed out the inflamed green mucus and that was very painful indeed. The mix emerged through my mouth into a kidney bowl held by a nurse. Never mind that it was unpleasant, it worked. I had it done twice but on the second occasion I knew at least what to expect. MRSA was unheard of and the lesson of Semmelweiss acted on.

Karel Popper at the Youth Dormitory

What had been significant to me in the youth dormitory was getting to know Karel Popper. Karel was my age, may be bit younger. He had straight black hair and blue eyes and turned out to be a genius, but before I found out about the breadth of his knowledge he taught me the elements of trigonometry at night under a very weak light bulb, it can’t have been more than 30 W, another of the many subjects we hadn’t been taught at school.

Exactly three long years later, when I started a National Certificate course in Mechanical Engineering at the Regent Street. Poly the acquaintance with that part of mathematics came in very handy. By that time Karel had been dead for two years and the Jewish intelligentsia had been robbed of a mind it could not afford to lose.

Father’s Work on the Timber Yard

My father’s first job had been stacking timber in the open on a timber yard. The Reich, every aspect of it, used prodigious amounts of timber, from ammunition boxes, to wooden bunks in ghettoes, prisoner of war camps, slave labour camps, to watch towers in the same establishments and timber was found, or simply taken, from the Baltic and Polish and Ukrainian forests.

It was also treated as if there was no war. The trunks were stacked upright to dry out, cut roughly into boards, the boards were stacked horizontally with a distance piece at intervals to allow air to circulate and only when it had dried naturally was it fine-sawn or machine-planed and used. That takes years, one cannot hurry nature, and the resulting timber does not warp, shrink, twist or bend after the final process which is what it does here where timber is vacuum dried. I think that my father liked the work, it reminded him of his years in the Urals working as an Austrian POW on the Trans-Siberian Railway.

It made him fit although he was not the 20 year old any more. He had also started with great enthusiasm but soon realised that he had to slow down, like everybody else, so as not to spend more calories than contained in the daily ration.

The Danish Invasion

My father remained in the loft for a long time. I remember Danish Jews arriving and at first also being dumped there and they arrived at the beginning of October, so he must have remained there for at least three months and winter was not the time to be there.

The Danes, who kept themselves very much to themselves, there was the obvious language difficulty, not insurmountable, English could have been the intermediary language, were eventually allotted a house in the ghetto. They had the support of their government back home which seemed to make all the difference in spite of the German occupation of Denmark.

They were returned to Denmark on 15 April 1945 in a convoy of cars provided by the Swiss Red Cross. None had been deported to the East. Amazing what political pressure, even on Nazis, could do when people were prepared to exert it. Vichy France was the exact opposite, they had fallen over themselves to please by collecting and imprisoning Jews before the Germans had even asked them.

The Dissolution of the Ghettowache

On 16 August 1943 the Ghetto-Kommandant ordered the dissolution of the Ghetto- wache. The Ghettowache, or ghetto police had until then consisted of young Czech Jews who, so I believe, had worked on the Prague cemetery before I had arrived there.

They had probably imagined themselves to be on hachsharah preparing to go to Israel where they would fight Arab marauders. They therefore behaved like a group of soldiers by drilling and, when formed into a police unit, continued to give the appearance of a military unit.

In that they may have taken their cue from the Czech Gendarmerie whose job was to stand guard at the main gates and to accompany us on work outside the ghetto and, anyway, police did wear uniform, but common sense would have suggested to avoid being conspicuous. Without realising it they took a risk because unbeknown to this Jewish brigade there had been a ghetto revolt in Warsaw three months earlier (19 April to 10 May 1943) and there had been an uprising in the ghetto of Bialystok which lasted from 16 to 21 August.

To forestall anything similar action by a trained group they were sent to Auschwitz and were replaced by older men. My father joined up and became a member of the new Ghettowache. They worked shifts and my father moved into their billets some time later.

Transportation to the East

From the moment one arrived in the ghetto one was liable to be sent East, even on the next day. That is what had happened to my friend Kurt Diamant and his mother. To arrive late in the ghetto meant one had missed transports.

We had arrived on 14 July 1943 but no transport was sent until 6 September 1943, when 5,007 persons were sent to Auschwitz of whom only 38 survived. Just like his job in Prague had protected us from being sent any earlier to the ghetto so his appointment to the Ghettowache protected us until the last clearance but not beyond even though 12,000 inmates remained there and, together with those whose death march destination was Theresienstadt, were liberated there.

It was not a complete liquidation as had occurred with ghettoes like Lodž, Minsk, Bialystok , Warsaw, etc. We missed 5-No. transports totalling 12,510 inmates of whom 1,129 survived (9.0%) but in the end it made no difference, both of my parents perished, but it gave me the chance to survive and to relate these unhappy deeds.

The Night Watch

What I remember most about my father was him guarding the crossing of the main road to the Kommandatur, and of the footpath at right angles to it, at night. The main administrative building, which had also been one in its previous existence, was on the town’s central square. That is where the Germans, mainly in SS uniform, had their offices.

Their living quarters lay outside the ghetto. The road they took to and from their quarters to the Kommandantur was fenced with close-boarded timber fencing on both sides. However to continue this separation between the extremes of races across the square would have made Jewish pedestrian traffic, and there was only pedestrian traffic, impossible.

Therefore a hinged bar with a counterweight, similar to a railway crossing, was installed and a ghetto policeman put in charge of it. His job was to keep an eye on the main road in both directions and, when he saw a German approach in the distance, to lower the gate to prevent Jews from crossing, i.e. to keep them at a safe and unpolluting distance, to salute as the German passed and to lift the gate once he had passed, a thoroughly humiliating task.

During the day he would have been kept thoroughly busy as every one of the German administration would pass and re-pass at least once during the day, and not necessarily in groups. There was no time for thoughts of one’s own, to look both ways and to judge distances required concentration.

In the dark and in winter it gets dark early and it gets light late in these parts, the task was infinitely worse because the lighting was poor and he therefore couldn’t see and a German approaching on a bicycle would be approaching fast.

It was also done in all weathers, in summer very hot, in winter very cold. However night-time was worse. There was the 8 o’clock curfew and well before that the streets would be empty and after 8 o’clock the junction would be completely empty except for those with special passes and the barrier could be left in the “down position and only opened on the odd occasion, although the ghetto policeman had to keep well awake for the odd German working late who had to be saluted.

However, as there was not the daytime hustle there was time for one’s own thoughts. I used to visit my father when he was on duty at the crossing just before the curfew as the room I shared with others was nearby, or not far.

Nothing was really very far, the town was quite small. That was why it was so overcrowded. It had been built for 5,000 soldiers, and their horses, with the terraced hoses built into squares with a central communal courtyard for the officers, their wives and civilian support and their wives and children.

On those occasions nobody was about and he talked about food in the past. That was terrible even if natural. During these quiet hours without much distraction he, or the body, would become aware of what was missing to sustain life, namely food.

In ordinary times one would get something to eat, wait for the next meal which was reliably due shortly or such a situation would not occur. But just thinking about it, or the reaction of the body to its absence, also known as hunger, produced the digestive juices ready to receive and to deal with food when no food would be forthcoming.

It was a vicious circle. The less was forthcoming the more one though about it, the more digestive juices were produced, the more hungry one felt. The body then fed upon itself. First all the fat was used up, then muscles wasted away, after that only skin and bones are left. The best one could do was not to think about it. Easier said than done.

My father had not only been fond of food prepared by other but also knew a lot about it, its preparation, had shopped, cooked and baked at times, in Berlin as well as in Prague. In Berlin when his friends came for a game of cards, in Prague to make best use of what he could get clandestinely, some of it one wouldn’t have touched in normal times.

To think about those days, particularly the pre-war days in spas, was really suffering. There may also have been other thoughts to trouble his mind. Should he have put more effort into emigrating? Others had managed but we had no relatives at all abroad. To just go across the border may have been easy, particularly with a Czech passport but, just looking at the map and being aware of the agitation of the Sudeten Germans who wanted to be incorporated into the Reich, had it ever been far enough?

It obviously hadn’t. And, with a Czech passport had the chances of obtaining a visa to go overseas not been better than with a German one which had a big “J” stamped in it? The answer now is that it would have made no difference and emigration too was a step into the unknown with its language and skills difficulties and there had already been five years to think and talk about what “might have been”. My parent’s lot, and that of all other victims of the Nazi era, was not an easy one and their despair difficult to grasp.

Dr. George Glanzberg

The first transports which we had missed were “Dl” and “Dm” which left together on 06.09.1943 with 5,007 people. On it was my teacher, Dr. George Glanzberg and I said goodby to him on the assembly platform. We mouthed platitudes about seeing one another soon again but somehow we knew that staying behind in the ghetto was safer than being sent to an unknown destination. Only 38 people survived and Dr. Glanzberg was not among them.

Move to L418

I didn’t stay long at the youth dormitory within the barracks and was moved to a room in one of the houses. Its designation was L418. The layout of the ghetto was to a square grid where “L” stood for “lange” or lengthwise and “Q” stood for “quer” or at right angles, just like North and East in some American cities.

I had been convinced that it had been called L418 but only a few years ago one of the boys assured me that it had been Q609, either could have been the same building.

There I shared a room with six other boys of my age, give and take a few months. All bar one were Czech speaking. This exception had come from Germany, was younger than us and his only relative was an uncle who had been decorated with an Iron Cross in the Great War.

I don’t know what happened to his parents. It was an unusual case, normally German speaking inmates, children, young people, adults and the elderly were kept together, language problems would have kept them apart anyway, the younger generation of Czech Jews didn’t speak German any more as their fathers and forefathers had done when Bohemia was still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and German was the first language within it.

Czech Jews had been the first to arrive in the ghetto, all members of the Ältestenrat and the heads of departments were therefore Czechs. Gradually German and Austrian Jews arrived and some of them died there or were sent on but while they were in the ghetto they complained that their interests were not looked after and a more equitable or representative mix of members of the Ältestenrat was agreed.

I was fluent in Czech, had arrived on a transport of Czech Jews from Prague and was categorized as a Czech youth, my Berlin origin notwithstanding.

My Room Mates

I am glad to say that all of my fellow room mates were intelligent, some outstandigly so, they were good and inspiring company and we never fell out about anything and, considering that living conditions were very crammed indeed, with bunks three beds high, that was quite an achievement.

Neither though did we form any friendship or attachment, they were too individualistic for that and each of us came from a different background.

Karel Popper and Pavel Kling

Two of the boys were outstanding, Karel Popper, whom I have already mentioned, and Pavel Kling. Karel Popper knew not only more mathematics than I was ever to know even though later it became one of the subjects of my studies. He had already introduced me to trigonometry, he now introduced me to elementary differentiation and integration and to volumes of rotation, which is a natural progression.

He kept a diary in symbols, something he said he had picked up from Leibnitz, a mathematician, contemporary and rival of Isaac Newton. He also knew more philosophy than I shall ever know and was a follower of Baruch de Spinoza, a Dutch Jew (1633-1677) of Portugese descent who was excommunicated by his synagogue for holding views incompatible with orthodoxy.

He knew all there was to know about chemistry but his main contribution to my neglected education was an introduction to the philosophy of politics which made Communism, Socialism, Capitalism, all meaningless words before I met him, take on a meaning and definition. He organised a weekly tutorial with a mathematician, one Otto Fischer whom I was to meet again later.

There were four of us, Karel, Paul, Paul’s brother Alois and myself and Mr. Fischer taught us spherical trigonometry, something every sea and air navigator uses to get from A to B on the spherically shaped surface of the earth, and other things, but I can’t remember them now.

Karel’s father had been a brewery engineer, a high position in a country famed and proud of the quality of its beer, Pilsener and Budweiser lager beers are very much of Czech origin. His parents were Prominente, that meant that they lived together, not separated like mine, had far more living space and, possibly more food, better washing facilities, privacy.

An equally, if not a greater benefit, was protection from transportation which lasted until the last clearance of the ghetto. The reason for the creation of this class system, could be ascribed to the Germans pursuing a policy of divide et impera for reasons of their own.

There was a time when they felt guilty about persecuting those who had fought bravely on their side and had been decorated but they changed their mind on that and prohibited Jews from wearing their medals, so it is difficult to fathom and brewery engineers and scientists did not count on that scale and yet some were included.

Unfortunately for society Karel Popper did not survive. I understand from Paul Kling that he died in Gleiwitz. If one was sent down the mines there then one never saw the light of day again.

There is no doubt that during the relatively short spell during which I shared his company he widened my horizon considerably, a horizon which, due to the German restriction on Jewish education, assembly and movement, had been quite narrow.

The second room mate who made up what I had been missing was Paul, or Pavel in Czech, Kling. He and his elder brother Alois came from Brno, or Brünn in German, the capital of Moravia. They were Mischlinge, i.e. of mixed race, father Jewish, mother a Czech Christian.

Paul had been a Wunderkind, at a very early age it was discovered that he had an “absolute ear”, he did not need a tuning fork or a piano to tune his violin. He had performed in public from the age of seven. He needed no urging to practice, he practiced every minute of the day until he reached perfection.

His impact on me arose from his music. Music had not played a part during my early Berlin days. Neither of my parents played an instrument - their respective early years had not permitted that. We had a gramophone and some Caruso discs and I had a few violin lessons before we left but I hadn’t taken to the hard work naturally and wasn’t pushed, primitive scraping is not that pleasant.

Attendance at public concerts was not permitted to Jews so that the potential of the violin was never made clear. Things were no better in Prague. After the occupation we had to hand in our radio and the violin. There was no music until I moved to L418 in the ghetto and then it really hit me. I had heard about it but had never heard it.

There are people who describe Theresienstadt as a concentration camp. It wasn’t. The best example of the difference I can give is this: a few days after meeting Paul I asked him to find somebody who knew the words of the Eroica, the choral work by Beethoven of which I had heard.

The words are by the poet Schiller. Three days later I had them in my hand and I still remember them from that day. (Freude, Freude schöner Götterfunken, Tochter aus Elysium, wir betreten feuertrunken Himmlische dein Heiligtum. Deine Zauber binden wieder was die Mode streng geteilt, alle Menschen werden Brüder wo dein sanfter Flügel weilt).

In a Concentration Camp there was no paper, no pencil and certainly not the time or mood or inclination to even think about it. Paul was a complete artist, he would let nothing get in the way of his playing and he would never, with an eye to the future and to his opinion of himself, play second fiddle, whether in a large or a chamber orchestra.

He would entrance us with Paganini, tell me about the fundamentals of music from what a cadenza is, to recapitulation, a fugue or double stopping. At last I heard the inspiring violin music, or the first violin parts of music by Brahms, Saint-Saëns, Schubert, Mozart, Faure, J.S.Bach, Teleman, etc. and that made life more bearable or rather it made one forget the worst aspects of one’s surroundings, it was an escape.

He was fortunate for several reasons. The Germans, for propaganda purposes, to deceive the world and hide their real purpose, had decided to encourage artistic activity, particularly music and there was plenty of talent.

They had stolen musical instruments from Jewish homes even before the owners were deported and the rest of their possessions were seized. To further their aim they had sent some of these instruments to the ghetto and Paul had picked a good violin and a good bow, each equally important.

Among the inmates were a great many very good professional performers, leaders of Czech orchestras, the competition was first class. As all he wanted to do was to play and he had the opportunity to do so his stay in the ghetto was not a waste of time, as it was for most of us, but a continuing development of his abilities and ambitions.

Being a Mischling too had very significant advantages. Until the last clearance of the ghetto between 28.09.44 and 28.10.44 those of mixed race were protected from transportation to the East. Also, because they still had a home and had at least one parent at that home who was not Jewish and could therefore move around freely, they received food parcels. Paul admitted without hesitation that his stay in the ghetto had been fruitful and enjoyable and not many can say that.

He and his brother were sent to Auschwitz during this last clearance, survived the first selection, were sent to a slave labour camp, survived that, went home, they had a home to return to, after their liberation.

He then left Czechoslova-kia and went to Vienna to continue his musical studies and career, did very well everywhere, both as a soloist and as a first violinist and when he felt that his time as a performer was drawing to a close he became professor of Music at the Victoria University, Vancouver, Canada where I found him through Bëit Terezín where he gave the occasional master class.

He had taken Austrian citizenship and the Austrian government bestowed on him their highest decoration. He married a Japanese harpist and they had a daughter who became a paediatrician at a major US hospital. Shortly before he died in January 2005 they had moved to California.

I don’t know much about his brother Alois, Pavel never gave me his address, they had been close but had fallen out over something. Alois too was very musical and a very gifted mechanic and we worked in the same workshop.

After the war he too went abroad. Although, strictly, non-Jewish, he went to Israel, worked for the Israeli Air Force on engine maintenance, then went to France, married a Czech girl there and worked for an American optical firm. He died a few years ago some-where near Paris.

Other Members of the Room

George, or Jiří, was a tall and well-built fellow who worked in the timber workshop, part of the same complex as the metal workshop. He did not really participate in any of our discussions and spent most of his time between end of work and curfew with his parents who too were Prominente.

That made sense, their washing facilities were better. I don’t know anything about his parents. George suffered from impetigo on his legs, an infection causing running sores which meant that he had to constantly change his paper bandages.

The medicine he took had a red dye as its main ingredient and was in pill form, or it was found that a dye was effective against this particular bacterial infection said to be contagious although none of us became infected and we couldn’t have lived together any closer.

I can’t remember his family name and could not therefore trace him. I understand from Paul that he survived and went to the USA but how he managed in a labour camp without his medicine I can’t imagine. Of the last member of the room I cannot remember either his first nor his second name and therefore, again, I couldn’t trace him. He was very intelligent, very friendly, made contributions to our evening discussions.

Unfortunately for him he wore very thick glasses and that would not have endeared him to Dr. Mengele. He stood no chance. His parents too were Prominente. We also had an occasional visitor, a boy keen on watch repair who could make very small holes through metal using heated, hammered and filed sewing needles and a small bow and string wound around the needle.

Holding the flat end of the needle in a bearing and pushing the bow forwards and backwards, thus turning the needle clockwise and anti-clockwise made for a primitive drill, very impressive.

He was also keen on capitalism which he explained in Marxist terms. When, after the war, the Communists in Czechoslovakia made much of dialectic materialism, which explained everything and was the key to salvation, at least I knew what they thought they were talking about even if that wasn’t what they said, they were adept at mental acrobatics just as they had been in 1941 when the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact which had made them pro-Nazi and excused everything and the subsequent invasion of Russia turned them anti-Nazi and pro-West.

As I was incapable of double-think and nothing could hide the reality of their anti-semitism, the victims of their show trials were all Jews, we parted our ways.

Prominente and Mischlinge

I have already mentioned Prominente, Mischlinge and artistic performances and this may be the right place to describe them before proceeding with my work in the workshops since the first two were a source of keenly felt social division.

My room was certainly not a cross-section, or representative, of the rest of the inmates of the ghetto. I use the words “inmates” because they were neither free, they could not leave the ghetto, neither were they prisoners in the concentration camp sense because we still had our own clothes, some of our possessions, moved around freely until the curfew, were not directly ruled, intimidated or beaten by capos, there was no electric fence, there were no watch towers, the SS were invisible inside the ghetto, guarding us at entry, exit and work outside the ghetto was left to the Czech gendarmerie, there was a cultural life if you had the time and inclination to participate.

To have three boys whose parents were Prominente and two boys who were Mischlinge was very much out of the ordinary because there weren't that many of either. Both are worth considering.

Prominente

Very probably a German idea to serve their own purpose or needs, they did nothing just to benefit Jews. They were people, and I don’t know who chose them, who had achieved prominence in pre-occupation life.

In his autobiography Arnošt Reiser, b.05.07.1920 who arrived in the ghetto in the middle of May 1942, or 14 months before us, mentions in his autobiography that in October of 1942 transports started to arrive from Germany and Austria, before that they had come from the Protektorat, with Jews who had achieved high rank in the German Army during the First World War and had been highly decorated, and also some famous artists, writers and scientists, and that these “Prominente were given better accommoda- tion.

Arnošt is 8 years older than I am and took in more than I did. What he says fits in with what I know of my room mates. If they, say were 20 in 1914 then they were 48 on arrival in 1942. If they were married they lived together.

They were spared the anguish of couples who had lived a normal married life and were now separated from one another, both living in crammed conditions with people they didn’t know. They had much more room. I never visited such fortunate couple but rely on just two reproductions of water-colour ink drawings on the subject which is in stark contrast to the many other drawings showing very overcrowded conditions.

The drawing, by Leo Heilbronn, a reproduction entitled “Logoment d’un privilégié”, 1942-1944, on p.46 of the profusely illustrated French book “Le Masque de lad Barbarie, le ghetto de Theresienstadt 1941-1945”, the original being in the possession of Bëit Theresienstadt Archives-Israel, shows a settee with cushions, curtains, a lampshade, pictures on the wall, a bookshelf with books, a stove, a table with table cloth, cups and saucers, two chairs, storage drawers under the window recess and other items difficult to define.

All in stark contrast to two slightly larger ink and water colours by Frank Maurice Nágl called “Châlits dans un dortoir”, 1943, with three-tier wooden bunks, a ladder to get to the second and third tier, clothes hanging from nails, an attempt at a screen made of fabric suspended from string to give a minimum of privacy with very little room between the uppermost bunk and the ceiling, all very makeshift, utilising every square inch of space.

Space in a crammed ghetto obviously enhances the quality of life, lack of space diminishes it, is claustrophobic and is a condition from which the ordinary inmate could not escape from. The second, and equally, or greater, advantage they enjoyed was being omitted from transportation lists.

As being on such a list, or card, caused an apprehension and fear, acute mental anguish and more than what is now called “stress” to ordinary inmates, to be released from this fear of being sent to the unknown was an advantage of some magnitude. It must have come as a rude shock to realise that the Germans had changed their mind, to be on such a list and to be deported on one of the last eleven transports which left within the space of 31 days.

At least they had a more comfortable time while in the ghetto.

Mischlinge

The definition of mixed race into two classes, first and second, originated in 1935 and was part of the Nürnberger Gesetze/Nuremberg laws which determined the relation between Aryans, meaning Germans in the first instance, and Jews, and laid the foundation for the complete exclusion of the latter from society.

The obsession, the cornerstone, which had economic overtones, of Nazi ideology were the Jews, the other one was to occupy, subjugate and rule the world by war and terror. What was confusing was that, described in terms of purity of race, it was doubtful whether there was such a thing as a monolithically pure race anyway, who is a German anyway, there was no Germany until 1871 and the various wars of the Protestant princes, the inclusion and exclusion of kingdoms in and out of the Holy Roman Empire, the Prussian advance into Poland made for many Germans having Polish names and certainly weren’t Nordic.

To confuse the issue none were actually Aryans because Aryans are Indians just as the real Gypsies, another group the Nazis persecuted, has come from India. For practical purposes the Germans had to resort to religion to define the individual’s race which too is unsatisfactory for purists and the whole issue was dodgy even if its consequences were very serious. One could only prove one’s Aryan -ness through entries in baptism registers going back at least two generations.

Thus there were Protestants and Catholics in the ghetto whose parents were Jews who had baptised their children. That did not count. As far as German law was concerned racially they were simply Jews because their parents were Jews. The offspring of two Jews was a Jew.

As an aside, had their Jewish great- grandparents baptised their children who, in turn had married children with and identical background then the present generation would have been classified as Aryans, tracing their background from baptism certificates, although racially they were as Jewish as I was although to find that out would have been highly inconvenient.

And there were cases like that. People did seek baptism to escape the restrictions imposed on Jews, those who wanted to remain in Spain after the expulsion of Jews in 1492 are only one example.

If only one parent was a Jew and the other one was an Aryan then the offspring was one of mixed race and of a higher order. Such inter-racial or, before the war, inter-religious marriages would have been most infrequent in Eastern Europe where both sides held strongly to their religious beliefs but they were common, or relatively common, in Central Europe.

It was usually Jewish men who married non-Jewish women. The man of such a union was protected from transportation, e.g. Victor Klemperer, the author of a diary describing Dresdeners during the Nazi period and a pretty awful lot they were.

If the Aryan spouse died or there was a divorce, and the pressure to divorce was great, then the Jewish spouse lost the protection and was sent to Auschwitz. The children of that union had various degrees of protection which is not always clear-cut and varied with time. One of my school mates in Berlin survived by not wearing a star, presumably she didn’t look Jewish. On the other hand she worked, without pay, on the Jewish Weissensee cemetery.

The homosexual young Berliner Gad Beck, who had an Aryan mother whose family supported him, had to go underground and was helped by his homosexual German friends, was imprisoned and, but for the timely entry of the Russians, would not have made it.

His book, “An Underground Life, memoirs of a gay Jew in Nazi Berlin”, University of Wisconsin Press, 1999, is a very good description of early Nazi thuggery and of a young man persecuted as a Jew, notwithstanding being a Mischling, and as a homosexual who sees others caught by the relentless pursuit of other “under- ground” Jews by the Gestapo, amazing that they had the manpower to spend.

Gad was therefore an exception, having the support of the German part of his family and of the homosexual community which lead a double life, but then all survivors were exceptions. There was a third group who were one better than the 50/50 racial mix described above. Another schoolmate of mine at the Jewish Joseph Lehmann school, Fritz Behrendt and his brother Hans, now of Holland, only had one Jewish grandmother.

Both grandfathers were Aryan as was the other grandmother. His father was a 50/50 Jew as his mother, Fritz’ grandmother, was Jewish, and he had married an Aryan. Using four grandparents (of whom 3 were 100% Aryan and one 0%) and two parents (of whom one was 100% and the other one 50% Aryan) into the important arithmetic of Jewish blood content, the brothers had 450 : 6 = 75% Aryan and 25% Jewish blood and that dilution made all the difference.

Fritz was even called up into the German Air Force, passed his medical and his aircraft recognition test with flying colours but, due to the fraction of impurity of his blood, was kept in the reserve and was not sent to the front, was therefore saved from the Heldentot (hero’s death) to which all of his fellow recruits succumbed when the Russians broke the siege of Leningrad on 15 January 1944.

Thus it was his Jewish grandmother who saved his life by her very existence, one of the perverse aspects of Nazi Germany. Many tried to hide and were embarrassed by such skeletons in their cupboards, Fritz, who got on very well with his Jewish grandmother anyway, had every reason to be proud of her.

The boys and girls of my acquaintance in the ghetto were of the 50/50 kind and were of my age. For some to have been taken from their parents at the age of 14 and to have been put into a ghetto with Jews with whom they had very little in common must have been traumatic at first.

Many seemed to have enjoyed their stay and many stayed on and survived in the ghetto. They found many who were in the same situation, the Jewishness of others was minimal in most cases and they lived a charmed life compared to others. Firstly, they still had a home, none of us common folk had. Secondly they had at least one parent living in that home who was concerned with their welfare.

When it became possible to send food parcels to the ghetto that parent would send them. Very, very few Jews benefited from this opportunity, certainly not German Jews. Germans wouldn’t send food parcels to Jews, to be seen or perceived to be friendly to Jews was dangerous.

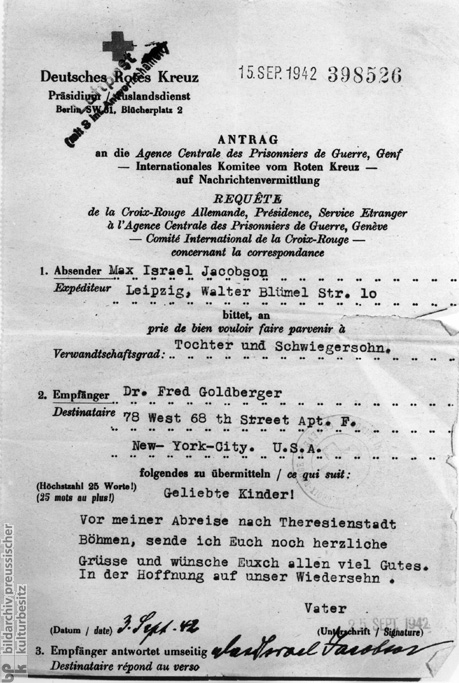

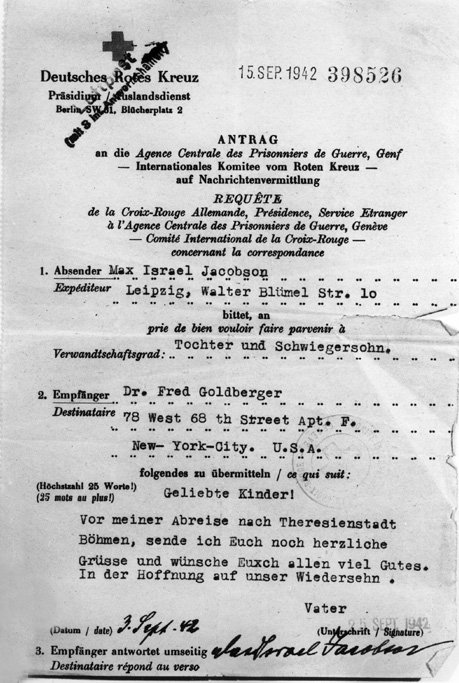

Quoting from the correspondence with a pre-war German immigrant to England who was sent to Australia on the “S.S.Dunera” whose father was sent to the ghetto, became a Haus-älteste there, i.e. was in charge of a house of elderly German Jews and who survived there and joined his son in Australia after the war, this father received tins of sardines from an aunt in Switzerland.

Sardines were a valuable commodity - they didn’t deteriorate, were small in volume and could be exchanged for something else. Again an exception from which one cannot possibly generalise.

The 50/50 Mischlinge or mixed race children were also, just like the Prominente, protected from transportation to the East until the last clearance between 28.09.44 and 28.10.44, although, as mentioned not all of them were sent. Because they remained in the ghetto they managed to get good jobs. By that I mean that it had a connection with food or was a job they liked and had other advantages. I knew one boy who had a permanent place at the public showers. Use was by ticket.

Tickets were allocated to everybody but far more people wanted and indeed needed a shower than got tickets. Just like those working in the bakery were given extra bread so he was given tickets, it was a perk. He didn’t need them because he could have a shower all day. They could be given away or exchanged. Working there was as good as working with food.

The mechanics of their move into such desirable and life enhancing occupations was very simple. “X” arrived on an early transport when the ghetto was still being created from the small fortress town.

The kitchens, etc. which were part of it were being constructed. “X” was able to find work in one of them. Between 09.01.1942 and 20.01.1943 no fewer than 36 transports left the ghetto for the East, or one very 1.5 weeks. “X” and others like him, 45,870 persons to be exact, left the ghetto and, say, half of them had been part of the working population or 23,000 people.

These 36 transports created 23,000 vacancies, a constant change. Among these vacancies were vacancies in kitchens and the bakery, food distribution, etc. A Mischling stepped into such a vacancy. Unlike his or her predecessor he or she, being exempted from transportation, would not vacate that job.

Until Sept./Oct.’44 it was theirs for the duration and some remained to the end. They had the best of both worlds. A home, a mother at home, food parcels which most of them didn’t need, security of tenure and, after the war, a home to return to, something none of us had.

The two monsters stalking the ghetto, hunger and fear, didn’t molest them. They were fitter than the rest. Being and looking fitter than the rest probably increased their chances of surviving the selection on arrival at the ramp at Auschwitz and the chances of survival in a subsequent labour camp.

There were exceptions to prove the rule. Petr Ginz, a fourteen year old, editor and force behind a hand-copied weekly called “Vedem”, (we lead) produced in great secrecy, a Mischling, was deported to Auschwitz and died there. His sister Eva, now Chava Pressburger living in Israel, survived in the ghetto.

My Job in the Workshop

I had never held a file of any shape, form or size and degree of roughness. I had never drilled a hole through metal, never mind sharpened a drill, heated and forged mild steel or swung a heavy hammer in precise rhythm with others to shape a red- hot piece of metal on an anvil. I did all of this eventually.

The trouble with learning, or being taught, a trade is that somebody has to show you how to do it, preferably somebody who knows how to do it himself. While he is spending time showing you what to do and how to do it he cannot get on with his own work.

So not many of the really skilled people, on which the progress of the workshop depends, are keen to spend time with a newcomer who may turn out not to have the dexterity required for the job. The same thing happened a few years later in London when I worked for a press-tool-making firm. So I was left to do rather monotonous jobs at first, like producing hinges on a hand-operated press.

The workshop was large, it had a bench running down the middle to which vices were attached and there were upright, free-standing electric drills and an electric grinder against one of the walls.

Half of the workshop made keys, repaired door locks, made small and large hinges for windows and doors in the ghetto and fitted them, and made prams for the German babies, or at least the metal parts, including fitting solid rubber tyres to wooden wheels, and putting the lot together.

The SS were very pleased with the chief engineer’s invention of converting a foot-operated sewing machine into a machine to hammer the cutting edges of scythes. That didn’t stop them from beating him up because he had had the temerity to sit down on a bench on top of the roof, the roof being grassed-over earthwork.

The chief mechanic was one Lode from the Ruhr industrial part of Germany, an incredibly skilled man. In the inner part of the workshop, away from the door and any natural light, were the tinsmiths from Vienna.

The tinsmiths cut out thin tinned (galvanised) steel from templates and bent, folded at joints, hammered it with wooden mallets and soldered the finished joints, producing buckets, coal scuttles and large water jugs. They too knew what they were doing and worked with great speed and assuredness.

A large opening in the wall led to the workshop next door which housed a forge with electric fan, anvils, an electric welder and the ornamental iron smith who worked for the Germans who didn’t mind benefiting from Jewish skills. The electric arc welder was given a pint of milk each day to counteract radiation.

The trouble, or one of the troubles, was that we had no special working clothes, like cotton coats or boiler suits, i.e. that we had to work in our everyday and only clothes, that we got dirty, particularly our hands, and that there was no soap to keep clean.

I was fortunate to work with a hunchback who had been a silversmith in Prague and had specialised in silver cutlery and had left behind for safe keeping his large collection of punches and dies with which the ornate handles are made, to resume work after the war.

I still feel sorry for him, with his obvious physical disability he stood no chance being selected for work on arrival in Auschwitz. He taught me how to sharpen high-speed drills, from very large, using a large carborundum grinding wheel, to very small drills, using a small hand-held and smooth carborun-dum stone, something that came in useful four years later.

Other attached workshops included the timber workshop where my room mate George worked, equipped with band saw, machine plane and machine circular vertical saw capable from mass producing anything from bunk beds to furniture. There was also an automatic machine making the wooden soles of clogs using a steel last, cam and follower, a piece of wood and a fast rotating cutter.

Working in between the metal and the timber workshop worked a very important figure, the scissors and knife sharpener who used a very large, wide and smooth vertically rotating carborundum wheel and skilfully took scissors apart, sharpened each blade and put them together again. To be blunt, without him the ghetto would have ground to a halt.

We did not wholly work for work’s sake. Germans as well as German Jews, or Jews in general, have what is called the Protestant work ethic, the curse, administered on the expulsion from paradise that you should earn your bread by the sweat of your brow, had taken root.

Much of the work in the ghetto, as long as it wasn’t connected with the German war effort, was creative, was for the benefit of fellow inmates, it took one’s mind off the pervasive grime and grimness with which everything beyond the workshop was infested. However the real reason for working was the meal, consisting invariably of a ladleful of soup, delivered to the workshop.

That arrangement, as already mentioned, made sure that only those working received these calories in addition to the basic ration which, in turn, was designed or calculated not to keep you alive. It is quite reasonable to suggest that most of the 33,521 who died in the ghetto (out of a total of 139,517 who arrived, were sent on or remained there) died of starvation because they were old, therefore didn’t work, therefore didn’t receive the extra ration.

As far as the workshop was concerned, this ration, or soup, was collected by two workers in an insulated container, i.e. outside metal skin, inside metal wall, large air gap in between, hinged lid with a tight seal, mounted on a trolley, from one of the many kitchens, one in each of the eleven huge army barracks.

The Germans must have produced millions of these food distribution containers, just as they must have made hundreds of thousands of large, identical, circular, waist-high, about four foot diameter , with hinged lid, field-kitchen type cookers in preparation for the coming war for use in the many types of prison camps they had in mind.

Neither were the identical reinforced concrete posts supporting barbed and electrified wire produced overnight. The job of collecting and ladling out the soup was done in rotation to give everybody a chance to carry out this desirable task. Desirable because the kitchen would always fill the contained to above the minimum to make sure that the two collectors wouldn’t run out which would have caused a riot.

One was therefore likely to have a little bit left over. Once it was my turn and indeed a little was left in the bottom. I scooped it up in my eating utensil/container.

One didn’t eat off plates, not suitable for soup, and all such containers or utensils were made of aluminium because it was light, didn’t break, was deep enough, and with a fitting hinged lid, practical. I rushed to my mother’s huge room in one of the 18th century barracks as soon as I could. By the time we had finished ladling it out, me scooping out the remains and getting to my mother’s the soup was cold.

There was absolutely no means of heating it, there was no means of keeping it and, in any case, she was hungry and gulped it down then and there. The result was a disaster, her system couldn’t cope with it, she had a gall bladder attack was rushed to hospital and survived.

That was fortunate because, although the very competent surgeons managed to treat their patients, the patients would later die because they did not have the reserve of strength, the fitness, to get over the shock to the system of the operation.

My instinctive action had done more harm than good because it was inconsistent, if I had been able to add to her diet consistently then her system would have got used to it, a one-off after months of so little that our stomachs had shrunk had caused her great pain.

Performances

There were, as already mentioned, an amazing number of public musical performances, talks and lectures on every conceivable subject, there was also a cafè with a band, there were composers and lyricists who produced ghetto-made musicals, revues and cabarets.

I heard about some of them, such as Brundibar, The Emperor of Atlantis, the evergreen Bartered Bride, Carmen, song recitals, Verdi’s Requiem where the choir changed during its many performances as some members were deported, their place being taken by new arrivals, any number of chamber music performances requiring only a small ensemble.

And that is only music.

The book of reproductions of ghetto paintings, watercolours, charcoal sketches and cartoons, “Le Masque de la Barbarie, le ghetto de Theresienstadt 1941-1945” published by the Cité de Lyon, put together by Sabine Zeitoun, reproduces a list of such performances and events, reproduced by permission from the archives of Bëit Theresienstadt, for the week 13 to 19 March 1944.

The chart has four headings: Theatre and Music, Cafè-concert, Talks on literature, science humanities, Talks on the science of economics and medicine, Talks on Judaism.

Each heading had between four to eight events per day. For example: Monday, 13 March: The Marriage by Gogol, Piano quartet: G.Klein, K.Fröhlich, R.Süssman, F.Mark (Brahms, Dvořák), Après midi d’ enfants (Lieder), Strauss ensemble, Cabaret John, Group Bunte. Thursday, 16 March: Pygmalion by G.B.Shaw, Cabaret John, Tosca by Puccini, concert for children, piano recital by Edith Steiner-Krauss (who is still alive and lives in London) (J.S.Bach), Swing Quintett, Strauss Ensemble, Group Bunte, Songs from Durra choral. On other days it was La Fiancée Vendue/Bartered Bride by Smetana. In between: Dr.Leopold Neuhaus: La superstition entourant le chiffre 13, Dr.E.Utitz: Locke et Hume, Victor Ullmann: L’écoute de la musique d’Emil et le détective, and, with some foresight, Dr.W.Mautner: L’importance du pétrol dans le système économique mondial, and at the bottom of the list: Aron Müller: Introduction de Pentateuque de Moise (en hébreu) and: Valtr Freund: À propose de l’humour juif, to cheer one up.

The list is impressive. The other side of the coin is that very few people attended. Ruth Bondy of Ramat Gan wrote to me on the subject: “….most of the working people had no time, no opportunity and no strength to go to all those lectures and performances, especially if they didn’t live in one of those big barracks where most of them took place, and had parents living in different barracks.

As to myself, during my 18 months stay in Terezín I only saw Prodaná Nĕvesta (the Bartered Bride) and Figaro because they were performed in L417 where I worked for some time and had connections there. I did not attend one simple lecture because of the Abendsperre (curfew).”

To others, older than me and Ruth Bondy, music aroused strong feelings based on their past. Gottfried Bloch, then a young doctor, now ninety as I write this, describes his first and only attendance at a chamber concert where Erich Klapp, a former assistant to the professor of internal medicine at the German University of Prague and now in charge of infectious diseases, a most dangerous place, was playing the cello:

“The concert took place in the afternoon in a former theatre, mostly empty. On the stage were the musicians, Klapp on the cello, and three other string players. They started to play one of the early Beethoven quartets. I still feel the painful sensation running through my whole body. I had not heard music for at least a couple of years. I suddenly realised that part of me had grown numb… I started to cry for the first time in all these months.

I had to leave after the first movement. Erich Klapp looked at me with a painful smile and an understanding gesture of farewell.….There was no place for delicate feelings, especially not for feelings connected with the beauty of one’s former life.”

My experience was different. Gottfried had experienced real Nazism since 1938, though he had always experienced anti-Semitism in The German Sudeten and the German Charles University.

I was 13 years younger and had experience of Nazism ever since I could remember and therefore had no experience of the strong emotions released by music. Even so, I only went to just one performance held in a corner of a loft, attended by a handful of people, and I did so only because Paul Kling was playing second violin (on the one and only occasion) and and Karel Ančerl (later to become a conductor) the viola in Schubert’s string quintet in c major, but then I knew the violin part by heart having heard Paul practice it so often.

It was really to hear the complete work. I now have a record of it by the Amadeus.

Stay in Hospital

I spent quite a long time in a children’s hospital. I was disturbed to discover that when passing urine I had seen blood. I reported that to a doctor. I was sent to a room in a children’s or young person’s ward for observation. Could I reproduce the passing of blood? No.

The suspicion was that I had nephritis but proof was needed. I don’t know what would have happened if I had contracted this illness considering the limited resources.

Meantime I was very well looked after, white sheets, a special diet and any amount of white bread which had been a luxury even before the ghetto. What pleases me most about my stay on that ward is that I was able to give my parents some of this bread when they came to visit me.

Of course they must have been worried about my health but fortunately and encouragingly, I never had blood in my urine again. There was no pressure to discharge me, may be there were no patients waiting to take my place and I occupied a bed for far longer than had been strictly necessary but then, may be, an occupied bed looked better than an empty one, it justified somebody else’s existence, so I served some purpose.

Throughout my stay on that ward there was a boy who was really ill, he was bedridden. His name was put on the list of those to be sent East and so he was taken from the ward on a stretcher.

He would have been put on the cattle truck with at least 49 others, 50 occupants per truck was the usual number but the stretcher would have taken up room. If he was permitted to remain on the stretcher that would have been the last act of kindness he would have received in this world.

As he was too ill to work anyway his fate was sealed.

When I returned much had changed. I was now in a different room with different boys, my eiderdown had been stuffed into the window to keep out the cold and my new room mates were reluctant to part with it.

The Visit of the Red Cross

First there was a rumour and there were rumours on everything since we had no hard facts at all. You could invent a rumour, spread it and see it return with embellishments.

Then the signs became unmistakable, something was afoot.

I wasn’t present when the representative of the Comité de Croix Rouge, Geneve, actually arrived, I was at work and so was nearly everybody else and I didn’t see the well-rehearsed charade on the day, but I could hardly have missed the preparations which had very serious implications for the 7,005 inmates, of whom 6,604 (94.3%) were killed who were sent to Auschwitz to make the ghetto look less overcrowded. As the September 1943 transport to the Familienlager, or what had remained of it, had been gassed during the night of 8 to 9 March 1944, this 15th to 18th May 1944 transport was sent to this now empty family camp.

After this human sacrifice a large bandstand was constructed on the central square underneath the windows of the German administration and, as there were so many musicians to chose from among the inmates, a band was quickly formed who played jazzy tunes and marches to give the appearance of a happy town enjoying itself.

One of the tunes, to which we gave Czech-German lyrics (Mein Vater ist im Ältestenrat, to jsem rád, to jsem rád, to jsem rád, my father is on the Council of Elders, I like that, I like that, I like that) was a good tune by the American Souza, but whether the Germans realised that or not I don’t know.

The front of houses along which the delegates were to proceed were painted to replace the original drabness. That was the oldest trick in the book first played on the Russian Tsarina Catherine by Prince Potemkin. The Empress, Potemkin, her lover, and foreign ambassadors were sailing along a river in territory recently conquered from the Ottomans.

Potemkin had arranged for workmen to assemble colourful facades of houses along the river bank and when the imperial barge hove into view to dress in peasant costume and raise three cheers as it passed.

When the river party disappeared round the next bend in the river the workmen would take down the prefabricated facades and re-erect them overnight farther downstream at another strategic point, leading at least the ambassadors to believe that the area was being well colonised.

This has been known ever since as “Potemkinsche Dörfer” (Potemkin Villages) , a mere façade, a sham. Now it was used to deceive the Swiss Red Cross and then exploit its international standing.

The difference was that the Swiss Red Cross was quite amenable to being deceived and fully co-operated. Even children were roped into this tale of make-belief that hid reality.

What were our thoughts? We had a high regard for the International Red Cross. It had a good reputation for being neutral, helping refugees, sending food parcels to and enabling correspondence to be delivered to prisoners of war during the First World War 25 years earlier.

We hoped that the delegates would take note of our plight and, at the least, stop the dreaded transports. Everybody had their own vision of the influence and good will of the Red Cross, otherwise they wouldn’t have wanted to come and see us. It made sure to conclude that something good, something positive, and improvement would result. Desperate people cling to straws.

The delegation, headed by the French Swiss Dr.Maurice Rossel and accompanied by the Dane Frants Wass and Dr.Juel Henningsen and those representing the German Red Cross visited the ghetto on 23 June 1944.

They strictly followed the route laid out for them by the German administration. They did not talk to a single inmate, never mind receive a delegation to listen to grievances out of earshot of the Germans.

Here one must add that the Red Cross or any Swiss businessman, and the Swiss did business in war materials with Nazi Germany on a gigantic scale and were paid in Jewish gold, including the teeth and wedding rings of the gassed at Auschwitz, moved freely across Germany and could not have helped but notice the many barbed wire enclosures other than prisoner-of-war camps.

They would have been listening to the Swiss radio and would have known that news of the extermination of Jews at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Familienlager had been given by the Polish underground to the representative of the Czechoslovak government in exile in Geneva, Dr.Jaromír Kopecký on 10 June and that Dr.Beneš, the Czechoslovak prime minister in exile in London was informed of this on 15 June.

The Allied radio stations then broadcast the news of the liquidation by the Nazis of Jewish prisoners. Partial knowledge of the death camps had been made public since the late 1942 when the Polish government in exile in London published the reports of its couriers. However there are none as blind as those who don’t want to see.

A week after the visit, on 1 July 1944, Dr.Rossel gave a copy of his report to the German diplomat Eberhardt von Thadden for forwarding to the Reich’s minister for foreign affairs. The report is reproduced in the French book “Le Masque de la Barbarie” where it occupies four large pages of very small print.

Since Dr.Rossel did no research of his own and stayed only for a few hours and did not see, or wanted to see, any of our dormitories or the food given to the old, it is quite clear that he copied the statistics, descriptions and conclusion from material given to him by the SS verbatim.

His report speaks of the ghetto in glowing colours, as if it were a health resort with a happy population without a worry on their minds. He did the Red Cross no favours by declaring: “la population ne souffre pas de sous-nutrition. Les rations accordées á Theresienstadt sont celles du Protektorat de Bohême et Moravie avec cette différence qu’on ne touche pas les œfs, le fromage et que le beurre est remplacé par la margarine…….ont calculé à 2 400 calories. Avec des suppléments pour les travailleurs lourds, les rations sons suffisantes” .

On 19 July 1944 the German Ministry for Foreign Affairs summoned a press conference of foreign journalists and, brandishing Dr.Rossell’s report, said that here was proof that the alleged persecution of Jews was pure enemy propaganda.

We didn’t know any of that. What we did know that there was no change, no let up - the higher our hopes the greater the disappointment. The Red Cross had let us down badly and if you couldn’t rely on such an institution whom could you rely on? Evil had triumphed.

54 years later, on 27 May 1998 at 9:30pm, BBC-2 TV broadcast a documentary called, most appropriately, “Betrayal”. It was one of a series of three called “Crossing the Lines”, “a series inside the Swiss ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross), the oldest and most secretive humanitarian organisation in the world, trying to find a place for itself in the 21st century.

But there are shameful secrets from the past and a new world disorder to confront. In the fractured conflicts of the future, will it have a role at all?” That is the blurb. It was written and presented by John Simpson, a veteran TV investigator and produced by Jane Dibblin.

It was Fulcrum West Production. I played a (very) small part in it and, through watching the programme and further enquiries about fellow witnesses, found Bëit Theresienstadt in Israel through which I found former fellow prisoners and who are still very helpful, one thing led to another.

What transpired in the programme was that the leadership of the International Red Cross in Geneva was actually very pro-Nazi as was Switzerland in general and it has a lot to answer for. Dr.Rossel was not only unrepentant but said that he would do the same again!

The Final Stage

Eleven transports carrying some 18,400 men women and children in rapid succession to Auschwitz, of whom 16,828 were killed, left the ghetto between 28 September and 28 October 1944.